Deplorable, Lousy, Godawful, and Required

People complain that politics are worse than ever. It happens to be true. But history contains as many examples of the contentious, weird, and wacky as the present—and those absurdities are actually vital to our democracy.

It is an election year again, and things are pretty nutty. The likely Republican nominee is a Mormon millionaire who used to like gay people but now does not. The second runner-up was a guy who doesn’t believe in birth control and once fought for professional wrestling to be deregulated. Then there’s our standing president, who slow-jams as a campaign tactic. As Macbeth once said about America’s presidential election cycle, “It is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.”

You may say to yourself, “The state of American political discourse is positively dreadful.” Or you may think, “Epistemologically, this election has brought America to a new low.” And according to a recent study, things are only going to tumble further down the purple mountain: Congress is more divided now than at any time since Reconstruction. The only politicians who succeed anymore are those who can speak to polarized sides.

But fear not. The absurdity and wonder of presidential candidates predates Romney, Santorum, and even old Wolf Blitzer. And there is no shortage of proof.

Let’s begin back in 1908, when William Howard Taft ran against William Jennings Bryan. The clinically lethargic Taft, a.k.a. “Big Lub,” didn’t really want to be the 27th leader of the free world. He was content with his dream to serve as chief justice of the Supreme Court. However, Teddy Roosevelt, the 26th president, had pledged that he would not go for a third round in office and thus sweet-talked Lub, his war secretary and the former governor-general of the Philippines, into running.

TR’s fellow Republicans did not take well to this. Just before Taft was to be nominated at the Republican Party Convention in Chicago, there occurred a “spontaneous and wild demonstration that produced a 49-minute stampede for Roosevelt.” Regardless of the flash mob, Taft clinched the nod. He then pledged to lose 30 pounds and not say anything bad about his opponent in order to win the presidency. Weirdly, it worked.

Taft served four unremarkable years in office. In 1912, he was challenged by, among others, New Jersey Democrat Woodrow Wilson, Indiana Socialist Eugene V. Debs, and Wisconsin Republican Robert La Follette, a rising beacon on the progressive side of the GOP. As governor of Wisconsin, La Follette, alias “Fighting Bob,” was popular with journalists for his anti-monopoly views. However, La Follette lacked a pivotal skill when it came to the media: pandering.

First, some context. presidential candidates are usually advised to be nice to the Press and feed them lots of greasy food on the campaign trail so they slip into catatonic states and cannot report any weird offenses the candidates commit. The worst thing a candidate can do, besides having past proclivity for weed or lying about time served in the military, is to, say, attend a banquet in honor of journalists and give a speech calling them “hired men who no longer express honest judgments and sincere conviction, who write what they are told to write and whose judgments are salaried.”

A half-century before La Follette sabotaged his presidential bid, there was a time when the country had more pressing problems, like moonshine and women with opinions.

But that is exactly what La Follette did, and that is why he never became president.

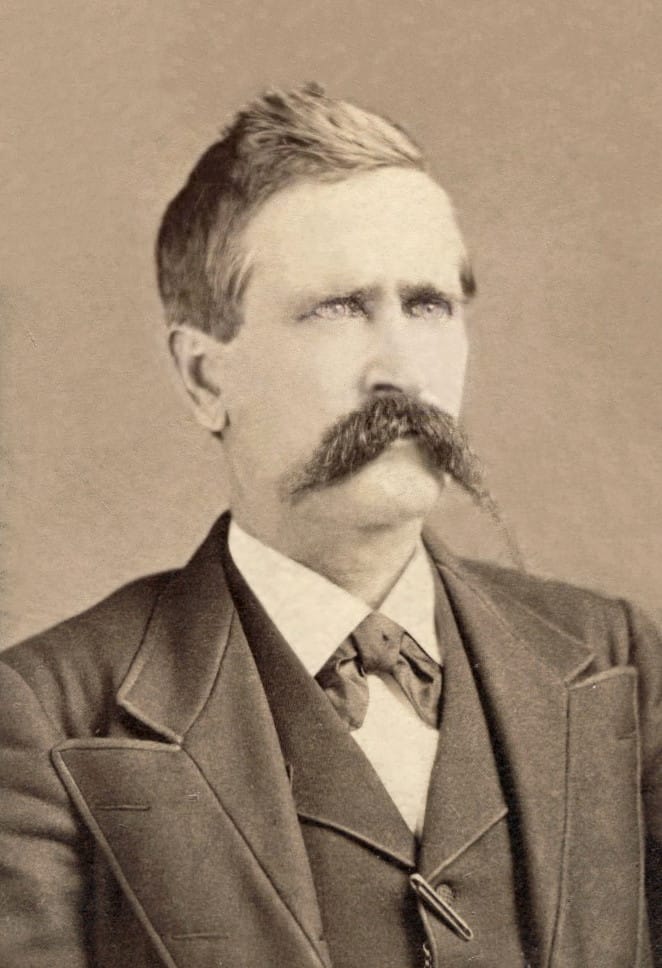

A half-century before La Follette sabotaged his presidential bid, before the strange breed of Republicans who believed in social reforms, there was a time when the country had more pressing problems, like moonshine and women with opinions. A time when people like Kansas Governor John St. John, who wrangled a wily mustache, lived and worked to make our country a better place.

After becoming the first politician in the nation to successfully outlaw alcohol in his state, St. John decided to take his civil servitude to the next level by running in the 1884 presidential election. His candidacy didn’t sit so well with the general public, but not because of the booze ban. Citizens were furious with St. John for deserting the Republican Party for that of the Prohibition Party. According to the Topeka Daily Capital, St. John was “burned or hung in effigy more than 500 times,” and also shot at twice for his move. Needless to say, he lost to Grover Cleveland. He died of heat exhaustion in 1916. (He is survived by his exquisite handwriting.)

Another candidate in the 1884 race was Belva Ann Lockwood, the first woman to be on an official presidential ballot. Widowed with child in her early twenties, Lockwood worked as a teacher and a journalist before going to National University Law School (now George Washington University Law School) at age 40. However, the school refused to confer on her a degree because of her gender. So what did Belva do? She wrote a letter to then-President Ulysses S. Grant demanding it. Her diploma came a week later.

Lockwood, a member of the Equal Rights Party, was a formidable candidate. She ran on an extensive platform, covering issues from women’s suffrage to Native American rights. She also knew how to play the press: Cannily, she told them that even though she couldn’t vote, nothing prevented a man from voting for her.

Alas, it is a sad but predictable fact that the media and America at large did not take to Lockwood. Newspapers dubbed her “Old Lady Lockwood“ and even her fellow suffrage campaigners deemed her a “Barnum.” (In their feeble defense, Lockwood did like to ride her tricycle around Washington, D.C.) She garnered just 4,000 votes.

A mere century after Lockwood’s loss, Ellen McCormack, a Long Island housewife, became the first female presidential candidate to qualify for federal Secret Service protection (illicit prostitutes notwithstanding). Girl power! However, McCormack was a member of the Right to Life Party, and she ran on one issue: outlawing abortion. Incongruously, the Republican party of yore refused to recognize the Right to Life Party’s existence. Perhaps this added to McCormack’s below-the-radar candidacy—according to the New York Times, not even her neighbors knew she was running for president (the Times also notes, somewhat icily, that McCormack “never held office in a local PTA.” Ouch).

A 2011 Tufts University study found that some kind of “outrage”—i.e., mockery, name-calling, exaggeration, character assassination—occurs on cable television or radio about once every minute and a half, and on nearly 83 percent of blog posts.

So by now you may have calmed down a bit about the 2012 race, which really pales in comparison to 1884, in my opinion. But let’s not forget our original question: Has political discourse really gotten worse over 100-odd years? Have elections gotten that much meaner and wackier, with the media leading the cause? A 2011 Tufts University study found that some kind of “outrage”—i.e., mockery, name-calling, exaggeration, character assassination—occurs on cable television or radio about once every minute and a half, and on nearly 83 percent of blog posts. The study found that syndicated newspaper columnists are more restrained in their fury, but less so than they were 50 years ago.

Naturally, blog rage and Fox News could not be observed and charted in the time of our forebears, but political vitriol has indeed persevered as an American pastime. One may conclude that, yes, political hostility is basically everywhere in our modern age. But, as the Tufts study somberly acknowledges, Americans consume media now in less uniform and consistent ways—if they are at all. It’s the grand quagmire of the ages: Ignorance will always be more dangerous than incivility. An insane bit of politicking—Sarah Palin here, Herman Cain there—can actually do wonders for the democratic process, bringing the glassy-eyed public to life and engaging them in the ritual that preserves their very freedom. Thus, the absurdity of politics is essential to our survival; it should be cherished.

Apropos of civic engagement, let us close with tale of one very special presidential loser, Wendell Willkie. An industrialist by trade with scant experience in politics, Willkie should serve as an inspiration to those entering politics with a mission to serve and inadvertently entertain. The Indiana neophyte emerged from near-obscurity with the help of grassroots organizing to grab the Republican nomination in 1940, leaving two senators and the New York district attorney in his wake. Unsurprisingly, Willkie couldn’t quite retain his political footing up against FDR and lost in a landslide.

But Willkie did not retreat softly into obscurity or become a spokesperson for the environment. Instead, he became one of Roosevelt’s closest confidants, published a best-selling book called One World, and allegedly had an affair with Madame Chiang Kai-shek.

Mitt Romney, take note.