Gentlemen, Formerly

A gentleman in 1720 could read Greek while mounting a running horse. Today’s gentleman reads GQ in the bathroom. From rapists to stylists, a history of the American gentleman.

Being a gentleman today means something very different from being a gentleman a few hundred years ago.

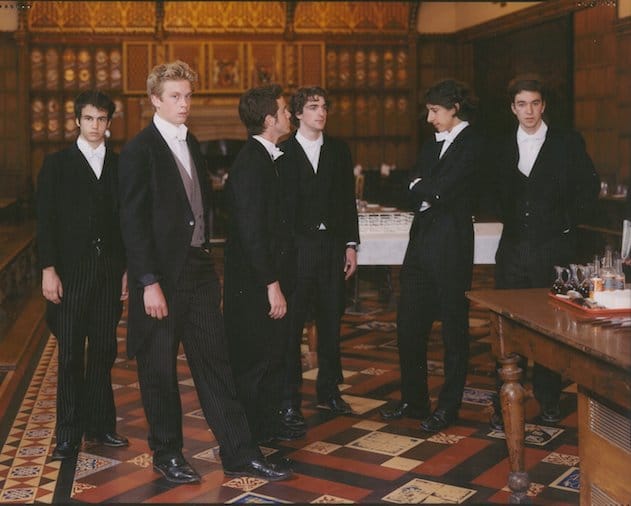

In the early 1700s, boys raised to be gentlemen would start learning Latin and Greek at seven, and by their early teens would know Hebrew and a handful of Romance languages. He’d read Homer. He would be able to carve busts, paint portraits in oil (and know how to grind his own pigments with linseed oil), and sketch animals and landscapes (which might be useful in battle). He would know how to sing, and to read and compose music. He would know cartography, geometry, astronomy, cosmography, and metalwork. He would know how to forge his coat of arms. He would know how to stalk a deer and train a falcon to hunt and return game. He would be able to wield a sword and a battle axe, and would be able to mount a horse as it galloped past. A gentleman traveled often, and kept a journal while he did so. He would pray every day. He would know the Bible front to back. And most importantly, the 18th-century gentleman would abide by emotional moderation, balance, and acceptance of all things—a sort of existential shrug to whatever misfortune landed on his mansion’s doorstep.

A noble family, land, and wealth were requirements, of course.

The Virginian planation owner William Byrd II, born in March 1674, considered what it meant to be a gentleman daily, sometimes hourly, in the secret diary entries he wrote in shorthand code in three-by-six-inch booklets. From a very early age, he’d been tutored with the The Boke Named the Governour written in 1531 by Englishman Thomas Elyot. Gentility was everything for Byrd; he used it to draw the line that separated his world of rabbit fricassee and a personal library from the deadly Virginian wilderness. Order, routine, reading Latin, and ascending in the House of Burgesses was his armor against the morbid colony. He prayed every day. He spent time calling on his friends. He exercised, and assiduously kept up his journaling. He gained political power. The question of exactly how to remain gentlemanly in the rough American Colony haunted him so persistently that one winter night, in 1710, when his wife was sick and the slaves on his plantation were dying from fever, he exhumed his father’s body (six years buried) hoping for some posthumous guidance on how to continue living calmly—with a sort of self-mastery a gentleman’s conduct required—in the face of so much death and sorrow. Apparently he got no answer, for he follows the exhumation diary entry with only, “Ate fish for dinner.”

And yet, Byrd is about as far from our current definition of a gentleman as one could get. He molested his servants, slept with his friends’ wives, and, at 67, regularly “played the fool” with a young slave girl, as described in his 9 May 1741 entry. He beat his servant Jenny and made another servant from England his sex slave, forcing her to make the two-month, cross-Atlantic passage. In his diaries, Byrd recorded his numbingly repetitive actions that are at once refined and deviant. Here is a sample from 1719:

I rose about 11 o’clock, having had my asses’ milk, and read a chapter in Hebrew and some Greek in Homer. I said my prayers, and had milk porridge for breakfast. I danced my dance [eight, cotillion-like dance moves, each one representing a virtue]. About one o’clock my Lord Percival came and stayed about half an hour. I read some English till 3 o’clock and then ate some brains. After dinner I put several things in order till 5 o’clock and then I went to see Mr. U-m-s where I drank tea and stayed till six and then went to Will’s, where I met my Lord Orrery and went with him to Mrs. Smith a woman that lives in Queen Street where I met with Mrs. C-r-t-n-y and to bed with her and rogered her two times. We lay till 10 o’clock and then rose and I went to Will’s and ate a jelly and then walked home and said Lord have mercy on me.

Byrd, in his deviance and misogyny, is exactly the opposite idea of today’s gentleman.

But, more interestingly, a gentleman today is equally distant from Byrd. The rigors, birthrights, and enormous skillset that a gentleman needed in Byrd’s time have blown away. A polite, self-sufficient, put-together man who reaches for the check usually qualifies now. Requirements of land, rank, and title have gone—along with, thankfully, “rogering” the servants. What you’ll mostly find in blogs and articles on how to be a gentleman today is tips on how to attract women.

WikiHow, for instance, tells us that to be a gentleman, start by taking regular showers, brushing your teeth, and trimming your nails. Pay for a woman’s drinks, all the time. Give up your seat for women on the bus. Don’t talk too much about video games, because that bores women. Don’t talk too much about yourself, either—a woman won’t think you’re intriguing if you tell her too much. Talk to her about music and politics, but avoid uncomfortable subjects, so, maybe, avoid politics altogether. Walk on the street-side of the sidewalk—women need to be protected from oncoming traffic. If you already have a girlfriend, pick up heavy things for her. Don’t talk about how hot other girls are around your girlfriend. Let her watch her favorite television shows instead of yours. Make it sound meaningful when you tell your girlfriend you love her. And most importantly, the one thing a gentleman must do is hold the door open for a woman.

But the variety of definitions only expands—into weirdly specific criteria—the further one looks. American Gentleman magazine gives a punchy definition on its cover that reads something like a high school pep-rally cheer: Passion, Etiquette, Fashion, Decorum, Drive, Determination. In a recent issue, articles ranged from Copenhagen Fashion Week to the makings of a “sophisticated barbeque” to a review of a Harley-Davidson. Business Insider this past Fall published a list called “The Unofficial Goldman Sachs Guide to Being a Man” that includes, “Buy a tuxedo before you are 30. Own a handcrafted shotgun. Don’t split a check. Desserts are for women—order one and pretend you don’t mind that she’s eating yours. Read more—it will make you more interesting at a dinner party.” Esquire’s “25 Skills Every Man Should Know” skips Copenhagen Fashion Week and barbeques and starts off with “How to Skin a Moose.” The list wanders from “How to Give a Good Massage” to “Buying a Woman Clothing” to “Google Efficiently” to “Console a Crying Woman” and “Kill an Injured Animal.” In such muddled definitions, I wonder if the moose killer and the fashionista would recognize the gentleman in the other?

The rigors, birthrights, and enormous skillset that a gentleman needed in Byrd’s time have blown away. A polite, self-sufficient, put-together man who reaches for the check usually qualifies now.

At least The Gentleman’s Handbook: The Essential Guide to Being a Gentleman (2013) is sensitive to the elusiveness of the definition: “It’s like trying to describe the feeling of true love or the look of perfect beauty,” the introduction reads. “The very vagueness and mutability of the concept is designed to keep us on our toes, so that we constantly strive to be the very best version of ourselves.” But, the Guide continues, we can be certain of few rules: A gentlemen dresses well, smells good, is social, is respectful of women (“but not too ”), and is witty and ambitious. Chapters include style and seduction, among others.

To discover that a gentleman today only has to brush his teeth, console his crying girlfriend, and barbeque with confidence would have terrified men like William Byrd II. Aside from not becoming a true gentleman, Byrd feared more than anything that he and his kind would become irrelevant in the New Colony’s future. He feared that all he had achieved to become a true gentleman, all his Greek and social climbing and hard-won backroom dealing, would be overwhelmed by the tide of immigrants whose mashed-up social customs would swallow up him and his friends. His class of elite and educated English gentlemen wouldn’t be needed or respected. I can almost see the beads of sweat forming on his forehead as he writes about the Scots-Irish.

Byrd’s fears weren’t exactly accurate, but in the time between 1720 and 2014 the definition of a gentleman changed: from an English nobleman to a Colonial aristocrat to a showered tuxedo-owner. The root of the change, as is so often the case, was money. In the 1700s in America and especially England, city merchants were becoming wealthier than the landed gentry. The newly rich—without the “breeding” that 17th-century English philosopher John Locke deemed essential for a gentleman—socialized with the “nobility,” blurring previously strict social boundaries. As one early 18th-century writer put it, “Any one that, without a Coat of Arms, has either a liberal or genteel education, that looks gentleman-like (whether he be so or not) and has the wherewithal to live freely and handsomely, is by the courtesy of England usually called a gentleman.” In a lineup of well-dressed men, it would have become hard to separate the entrepreneur from the old money. And after the Revolutionary War, the introduction of the democratic system of government meant Americans didn’t (ostensibly) need the rich nobility who formerly made and executed laws to govern a nation.[[1]]

Aristocracy (inheritance of titles, nobility) was left in England, and America’s “aristocratic” families fell prey to the markets. The middle class would eventually expand. Unlike in England and Colonial America, Americans not born into nobility or wealth had a chance at getting rich and to be buoyed up into higher social spheres. With wealth came access to higher education. Education meant access to position and title. Civil rights and feminist movements in the U.S. tweaked a gentleman’s standard of conduct to include respectful treatment of others. Gone for the most part, thankfully, are violent sexism, misogyny, requirement of wealth, racism. If anything, the revised “gentleman” may be one piece of evidence of the legend of the American Dream.

But our new model also hacked away at the requirement of the huge knowledgebase and skillset a true gentleman needed to deserve his title. The resulting gentleman is far more holographic, an image of refined man, without the required substance: He can own a handgun but need not know how to hunt; he should read a book for a dinner party but knows no more Greek than a few letters; he buys expensive paintings but can’t paint; he reads a list of to-do items in Esquire and does none of them. He probably can’t mount a horse at full gallop, lift a battle axe, or quote the Bible. He just plays the role convincingly.

When Byrd was 46, in 1720, he wrote in a letter to his friend in England that American Indian boys undergo an initiation rite called husquenawing:

This operation is performed upon the Indians of this part of the world at the age of puberty when they commence men, and is in order to make them forget all the follies of their childhood. For this end they are lock’t up in a place of security, and the physicians of the place ply them night and morning with a potion that transports them out their senses, and makes them perfectly mad for six weeks together. When this time is expired, they are kept upon meager diet for three days, and in that space they return to their understanding, but pretend to have forgot every thing that befell them in the early part of their lives.

Though Byrd obsesses over being a gentleman, what he seems to want more, here and in other entries and letters—ignoring the distracting social and historical context—is to reach his full potential, to feel like he’s crossed the finish line into adulthood, to shed his younger self as the boys undergoing husquenawing do. Maturity.

In his forties, Byrd wrote a “commonplace book”—aphorisms and life lessons from a man in the early evening of his life—written in over 500 numbered paragraphs. It ranges topics like advice from the ancient Greeks to sexual positions. But a huge part of the book is devoted to Byrd’s idea of maturity, of maintaining order and stability. Take, for instance, the commonplace book’s number 332: “Pythagoras was wont to inculcate, that no thing is so tyrannical as our Passions, when we have dethroned Reason, and usurped the government of actions.” He later wrote, “Tis a more noble conquest to get the better of what we love than of what we hate: For what we hate, if it do its Worst, can destroy our Bodys, but what we love, may destroy both Body and Soule.” One must be armored against selfishness, both his own and that in other men.

The revised “gentleman” may be one piece of evidence of the legend of the American Dream.

Byrd was riffing off John Locke in his definitions of maturity. As Locke wrote, “the Principle of all Vertue and Excellency lies in a power of denying our selves the satisfaction of our own Desire, where Reason does not authorize them.” To be a gentleman, to be mature, is to distinguish what we want from what we need, what we can do from what we should do. In Byrd’s words in his writings later in life, one must command oneself.

In Byrd’s commonplace book, there are many links to our modern gentleman, and to the Business Insider list. Just update the language and spelling and you’ve got savvy, professional advice for anyone wanting to move up in the world: “The great Secret of thriveing,” Byrd writes for number 356, “and being happy in this world, is to keep some worthy & profitable End in view, and after that to find out the properest means of attaining that End.” Also in accordance with today’s gentleman, Byrd does mention good taste—in clothes and art—as essential knowledge. There are also some similar life lessons: Byrd read Greek and Latin to access the wisdom of the ancients, whose big lessons—Byrd highlights in his commonplace book—were about preparing for the disappointments of life, and when encountered, to gracefully move on. That, I think, is an example of a gentleman’s maturity that everyone today, men and women, can relate to.

But even with the similarities, maybe we’ve expunged too much from the definition. Maybe we are falling short these days, trading a deep education for a tuxedo and quick reach for the door handle. Maybe the word has lost its formerly sleazy gravity to a fault. Is this just another shortcut of our time? Because, if you go back far enough, the word gentleman comes from Old French, gentil, meaning “highborn” or “noble.” And “noble,” for those who took Latin will remember, shares an Indo-European root of the word “to know.” As 17th-century French essayist Charles de Saint-Evremond wrote, “Knowledge begins the Gentleman.”

[[1]]: “The proper Business of Gentlemen…” essayist John Clarke wrote in 1731, “is to serve their Country, in the Making or Execution of the Laws.” Clarke also includes in a gentleman’s duties “finding out Ways and Means of employing the Poor” and “the Encouragement of Virtue.”