Go Your Own Way

The recent ho-hum reaction to the purchase and ensuing buyback of Frommer’s obscures one key fact: Guidebooks are creators of social change. A defense of their place in the canon.

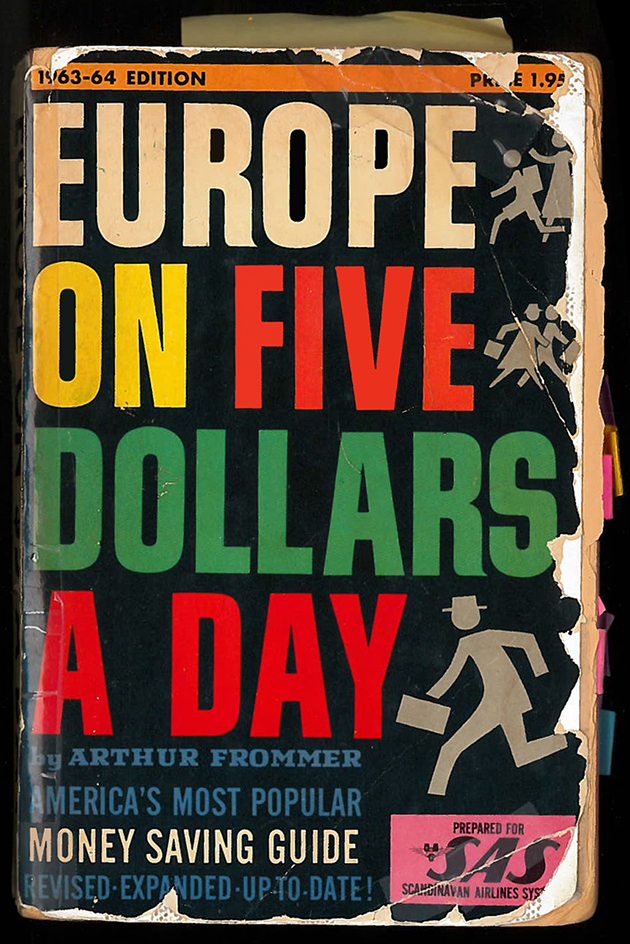

For a time, back in the 1960s, the big-name travel guidebook writers were bona fide celebrities. In 1967, Nora Ephron wrote a lengthy profile for the New York Times of Arthur Frommer, the fast-rising author whose then 10-year-old Europe on Five Dollars a Day would lead some 350,000 Americans around the Continent that year. Two years later, Frommer’s bitter rival, Temple Fielding, was the cover story for Time. The two men were at the leading edge of the late-1960s budget-travel boom (the UN decreed 1967 the International Tourism Year, with Human Rights having to wait until 1968), helping forge what we now think of as the beaten path, and becoming media darlings in the process.

Last August, Google bought the Frommer’s brand from then-owner John Wiley & Sons. Then, in April, Google announced that it would no longer print hard-copy editions of the guidebooks. The travel press burst out into hand-wringing and soul-searching, but for the general media and public, the news passed all but unnoticed. Two weeks later, Arthur Frommer himself, now in his early 80s, bought his namesake brand back from Google and announced plans to start publishing new books this fall. And once again, the mass reaction was a collective yawn, among those who took note at all. It was only last week—July 15, more than three months later—that the New York Times covered the story.

I can rattle off the authors of history’s iconic guides, in order. My default topic for party small talk is the evolution of recommended packing over the decades.

I, however, have been on the edge of my seat all along, endlessly fascinated, emotionally invested. I’ve followed the drama with the intensity typically reserved for die-hard sports fans—whooping at the highs, despairing at the lows, poring over the stats.

I am a Guidebook Nerd. I can rattle off the authors of history’s iconic guides, in order—Murray, Baedeker, Fodor, Fielding, Frommer, Wheeler, Steves—and tell you the specific innovation and authorial tone of each. My default topic for party small talk is the evolution of recommended packing over the decades. I’ve spent the last six years immersed in the history of guidebooks and their under-appreciated cultural impact, and I have come to believe that it’s high time they were granted their spot in the literary canon. Put simply, guidebooks are uniquely effective documents of a changing world—and, more to the point, they have been underappreciated actors in creating social change.

And my Exhibit A, the book that has become my personal lodestar, is the one that birthed Arthur Frommer’s iconic brand in the first place: Europe on Five Dollars a Day, originally published in 1957.

I first encountered Europe on Five Dollars a Day when I happened across a 1963 edition at a used-book sale several years ago. As with the best novels and memoirs, this book’s transportive powers gripped me the moment I began idly flipping through its yellow, brittle pages. Tiny flecks broke off as I turned to new sections, each one a time capsule of mid-century Europe, conjuring a world that was at turns familiar and jarringly strange to me, a child of the 1980s.

Here were charming Parisian hotels that charged two or three dollars per night, and Left Bank bistros recommended for their “buxom waitresses.” Here were tips on getting to each city’s American Express office, the 1960s traveler’s proto-internet hub for receiving mail, transferring money, and planning excursions. Here was Berlin, cleaved by a hulking wall and patrolled by heavily armed men. To the west: a vibrant city whose fatalism was manifest in its “erotic and exotic nightspots,” including one where you could ride a horse on the dance floor. On the other side, accessible only via Checkpoint Charlie: “the drab existence of East Berlin” and its “sawdust-filled” sausages. Even Frommer’s writing voice—populist, lyrical, low on cash but not on opinion or sense of wonder—conjured a bygone era. Postwar, pre-globalization, pre-jaded-backpacker. Norman Rockwell gone abroad. Witness his opening lines:

This is a book for American tourists who

a) own no oil wells in Texas

b) are unrelated to the Aga Khan

c) have never struck it rich in Las Vegas

and who still want to enjoy a wonderful European vacation.

Europe on Five Dollars a Day’s voice and imagery propelled me halfway around the world. I set off to travel around Europe in 2009, using this as my only guide, to see how it held up more than 50 years after it was first published. It was a strange and wonderful whirlwind of an adventure, one that became my own book, Europe on Five Wrong Turns a Day. By the end of my trip, after two months and eight countries worth of delightful discoveries, awkward encounters, and jarring differences between then and now, I could hear Arthur Frommer’s voice in my head.

What struck me most, on the road and in my later research, was not that change had occurred but that, in a very tangible way, Europe on Five Dollars a Day had guided the very path of cultural change itself, its impact manifest in every hostel-lined Amsterdam alley, every Roman trattoria whose tables bore more guidebooks than wine bottles.

Organizers of the Marshall Plan had encouraged middle-class Americans to travel to Europe, but it was Frommer who told budget travelers how to realize their Continental dreams.

Organizers of the Marshall Plan had encouraged middle-class Americans to travel to Europe as part of the rebuilding effort, but it was Frommer who told budget travelers how, exactly, to realize their Continental dreams, offering the guidance and reassurance that pushed them out the door. Earlier travel guides, such as Fielding’s and Fodor’s, had been aimed squarely at the steamer-trunk tourists, the elites who could afford to cross the ocean before the advent of commercial long-haul flights in 1958. The books’ highbrow tones and hefty weights matched their recommended daily budgets, dense with flowery digressions like the extended rumination on French wallpaper that Fodor included in his first Europe guide, in 1936. Europe on Five Dollars a Day marked a different approach, egalitarian through and through, from its budget to its pithy, straightforward prose—a self-help manual of sorts, starting with its descriptive, proudly populist title.

Think of Julia Child and how Mastering the Art of French Cooking changed the collective outlook on cooking, making it more accessible. That’s what Arthur Frommer did for European travel, showing the average American that this aspirational experience was, in fact, within reach. And in doing so, he created mass tourism as we know it.

Back home, I started buying more vintage guidebooks. The best of them, like Europe on Five Dollars a Day, not only informed but inspired, even implored: You’ve got to see this place, and you’ve got to do it my way. A world and a worldview, packaged for consumption, keenly aware of its specific audience.

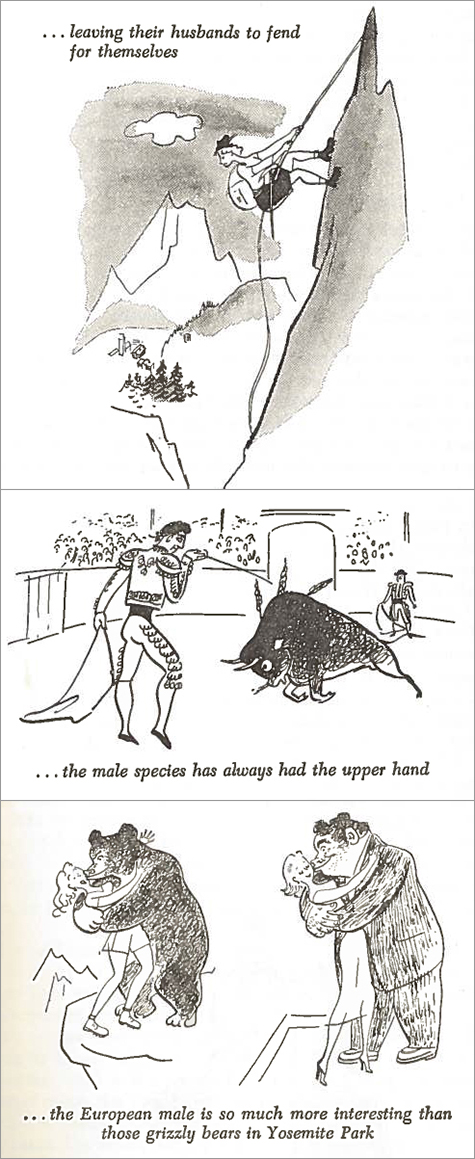

A 1963 copy of Eugene Fodor’s Women’s Guide to Europe offered advice for discussing “the suffragette movement” in Switzerland—where women weren’t allowed to vote in federal elections until 1971—and pronouncements like this: “I wouldn’t go so far as to say that the male sex is expendable. But if you can possibly manage it, I would suggest you try to work in one jaunt to Europe all by your little self.” A Havana guide dated December 1956 showcased a swingin’ paradise of gambling, rum, and “gay boulevards” lined with shops to compete with New York’s Fifth Avenue, the jaunty narrator unaware that the same month his book was to be published, 82 revolutionaries, led by Fidel and Raul Castro, would land on the island in the yacht Granma.

Like an epistolary novel, guidebooks tell a story in the curated aggregate of seemingly mundane components. Cafe recommendation builds on list of safety tips builds on political aside builds on confounding hand-drawn map, with the reader invited to project himself or herself into each micro-scene as the protagonist. Bit by bit, a narrative coalesces, narrow in time but vast in detail, showing a society’s values, aspirations, limitations, anxieties, and general state of affairs. A tale of two cultures—the author’s and the destination’s—and the state of relations between them in one narrow slice of time.

This is the crux of my nomination for guidebooks—the best ones, anyway—into the literary canon: They capture a specific historical moment better than any other form of literature I know.

They also stand out for shaping history, if not always intentionally, because of their authoritative reputation—they have long been the best insight into that which would be otherwise unknown. Most notoriously, the Nazis claimed to have used Baedeker’s guides in a 1942 series of air attacks on English cities, which would become known as the Baedeker Blitz. There’s some disagreement among historians as to whether the Nazis really did use the books, but this was Nazi propagandist Baron Gustav Braun von Sturm’s claim: that Baedeker had unwittingly identified the targets by highlighting Britain’s most beloved landmarks and towns, the places whose destruction would deal the biggest blows to the national spirit, including the cities of Bath and Norwich. More recently, shortly after American troops entered Iraq 10 years ago, Lonely Planet Iraq was pressed into duty for precisely the opposite goal, assisting officials who were prioritizing sites for protection.

Other guidebooks have specifically sought to right societal wrongs, like The Negro Motorist Green Books, a series published from 1936 to 1964, which guided African Americans traveling the U.S. in the era of Jim Crow. As civil-rights leader Julian Bond, whose parents used Green Books, told the New York Times in 2010, “It was a guidebook that told you not where the best places were to eat … but where there was any place.”

Today, of course, all of this sort of information is available in an internet search. I get it. I realize this is why the broader response to the apparent demise of Frommer’s guidebooks was an indifferent shrug. Well, that’s what Google’s for.

Yes. But. Beyond the standard book-nostalgist’s lament that digital devices are battery-dependent and bulky and theft-prone, there’s also this: Google is only good if you know what to look for—if you’re willing to sort through pages of possibly helpful content to find the genuinely helpful content. Good luck if you, like most travelers, are stepping out into the abyss with a general sense of a goal: I’m going to Paris. Help. Guidebooks can create information overload of their own, to be sure, but the mass of facts here is thoughtfully crafted, not redundant. Currency, culture, history, restaurants—all in one place, along with all manner of details you hadn’t thought to wonder about. A good guidebook makes you want to keep reading and discover its serendipitous rewards, just as a good city makes you want to keep wandering its streets.

The key is that voice, that fine-tuned curation that binds the pieces together into more than a scattered array of anonymous opinions and unverified facts. You don’t get that on Yelp, on TripAdvisor, or on Google. Of late, most guidebook lines have strayed from a focused approach, seemingly aspiring to Google mimicry, bloated, interchangeable, and bland—a world, but not a worldview. Canon-worthy reads have become as rare as a truly “undiscovered gem” on the tourist trail. Case in point, the modern Frommer’s Europe, whose 2013 edition has 1,070 pages (compared to 443 for my 1963 edition) and 29 authors, and is just flat-out less readable and engaging than its progenitor. And at two pounds, it’s heavier than an iPad.

Back in April, after I heard that Arthur Frommer had bought his brand back, I sent him a congratulatory email. He wrote back right away, his ebullience unmistakable, saying that his new books “will be very much like the early $5-a-day books: opinionated, intensely personal, practical, cost-conscious.”

As the New York Times reported in its story last week, the new books will be called EasyGuides, “an answer to the increasingly lengthy travel guides on the market that Mr. Frommer said were too long to be practical.” Most of the new guides will also be written by locals rather than freelancers brought to town specifically for the assignment.

Opinionated, practical, pithy, built on insider knowledge—actually, that sounds like a fairly good formula for a guidebook, circa 2013. I’ll withhold judgment until I actually read one of the books, but it does give me hope that, from Mr. Frommer or from someone else, our current historical moment will have its own iconic, enduring guidebook after all, one that speaks, in an authoritative, distinctive way, to who we are and where we’re going.