How to Paint an Oak Tree

A man who spent three years painting the same English tree repeatedly—in all weather, day and night—explains how exactly, and why.

Starting Points

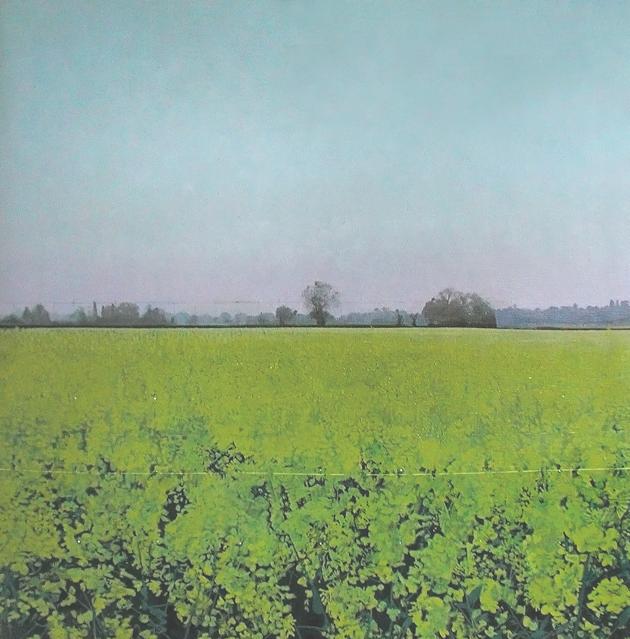

The natural world is visually very rich and constantly changing. From light reflecting on a mountain stream to the pattern of fallen leaves in a forest, nature is visually unpredictable and often very hard to see clearly. So I use painting to help me discover what is there. My methods are designed to clarify the complex colors and shapes I see. The approach is empirical, and I use science to help me observe. At the same time, a painting is more than a neutral record. My choice of colors is selective, and the picture expresses the associative and emotional concerns of the observer-painter. There are two sides to the way I work: one that takes place outdoors and another indoors. I trace the steps I took in creating Swallows at 9pm as a way to show my typical working process for a large painting. Seeing a picture develop from start to finish should help to get closer to the painting and to see how it can be both observational and expressive at the same time.

Outdoors

Outside, everything I do is to help my senses and my reactions adjust to the natural world. I want my work to come out of an intimate connection with a place. By the time I came to paint Swallows at 9pm, I had been working in the same field for six years, so I was familiar with its character. Each picture is unique and requires its own set of adjustments: for an evening picture like this, I arrive early to let my eyes adapt.

I strapped a pochade box around my neck so I could work standing up in the crop, which was chest high at this time of the year, and I mounted a digital camera on a tripod. I had a canvas seat to rest on, as well as hot coffee, snacks, fruit, and a tot of whisky. I take an extra set of old clothes—even in summer I can get cold if I’m standing still. I probably look like a tramp. I remember feeling utterly happy at this point, with my brushes, palettes, and rags, just looking...

I sometimes use photographs—taken years, days, or just minutes before—as inspiration. You can shoot, evaluate, adjust, and reshoot digital shots on the spot. I do not always start color studies with a photographic prompt, but I will take selective exposure shots as soon as I see the effect I’m after.

I had already taken photographs of the field of rape around six o’clock during a previous summer evening. (I had taken them because I felt that people don’t really look at rape as it responds to sunlight.) I wanted to use the bright yellow of the industrial crop to create an extreme contrast with the delicate tones of the trees, so I would paint in the early evening, when sunlight has a reddish color that makes the field look luminous.

I was set up under a clear sky, ready to go. I first put an approximate base key (a set of background colors that helps judge subsequent local colors more accurately than is possible on a white background) over the entire board using quick-drying acrylic. At six o’clock the crop started to catch the warm light of the setting sun, and I started to paint quickly in oil.

I make color mixes in clear, definite values, each one based on what I see and carefully compared with the other colors around it. This exacting comparison and mixing is fundamental to observational painting and is something students need to practice. Each color we perceive is effected by the colors surrounding it, and by analysing individual colors and their relationships to those around them, you can discover the unique character and lighting of a scene. Each study is a form of empirical discovery—and also a race, because the faster the light changes, the faster you have to work.

When I lay down the main colours, I start with big areas first. But in this case, they did not seem to work together. The light was fading very slowly, so I waited for something different to happen. I sat down and prepared another board in a darker key for the lower light that would come.

As the sun set behind me, the shadow of the earth rose on the horizon, reversing the usual gradient so that the sky above became brighter than the lower sky, which passed into a grey limbo. The crop was now in shadow but still luminous; detail in the trees on the horizon began to fall away. I noticed new, unimaginable red-blue greens within the rape.

I worked fast and in under an hour had laid down all I needed. At the same time, I took a series of selectively exposed photos. It was about nine o’clock when a small group of swallows flew straight at and passed me like bullets. The lead bird looked violet against the rape. I rapidly painted some colours to record this, then noticed the crimson light of a radio mast in the distance and included that, as well as the cold yellow of the headlight of a passing car.

I packed up and went home.

Computer Work

The next day my study looked both unfamiliar and somehow complete. These were both good signs. I transferred the photos into Adobe Photoshop to analyse as layers to help me discover the distribution of colors, a method that I first used to study colors in a field of corn. Traditional oil painting also has layers: painters, like Titian, built images up from separate layers of color, wet onto dry. This is the way I work. I use the colours from the study made outdoors to determine colors for the wet-on-dry layers that I build up on my painting in the studio.

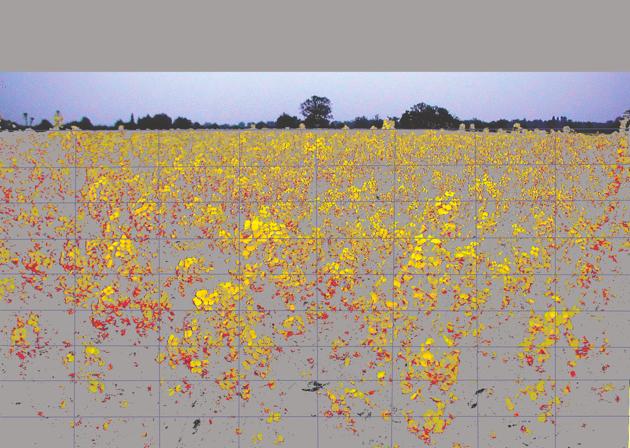

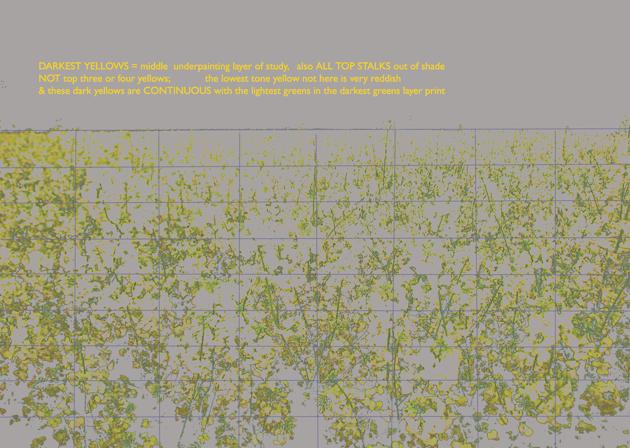

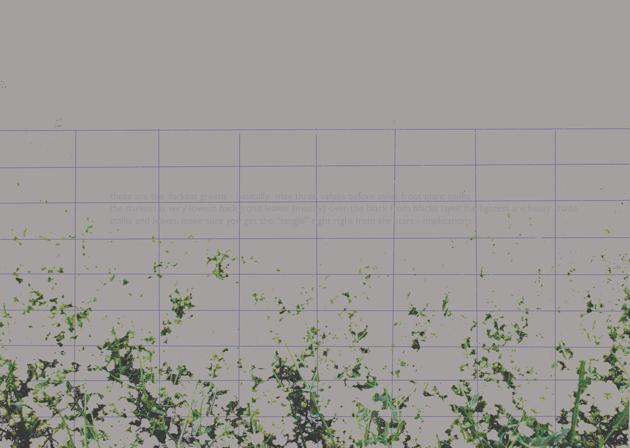

The photos I took at the rape field were variously exposed for different parts of the scene. To find the distribution of a color in the painted study, I first chose the photo that was best exposed to show that colour. I then used Photoshop’s selection tool to pick out that color in the photograph. Photoshop can then indicate every point in the photo where that color appears. This breakdown reveals details not obvious to the naked eye and can clarify the scene in an unexpected way. I could now use this information to guide the distribution of paint of that color onto the canvas. Only three photos were needed for this painting. After some trial and error, I could use this method to see the color distributions in a way that would help me to read the scene more effectively.

The layers also revealed the color distribution as a texture gradient, a regular increase in the number of texture elements proportional to the distance from the viewer. In experimental psychology, a texture gradient is a recognised depth cue. Since each texture is so closely associated with a color, it seems more appropriate here to refer to them as color-textures.

Some experimental psychologists are currently studying these types of association as an important new channel in visual processing. For me, they are a fundamental means with which human vision can disentangle or parse nature.

Studio Painting

I first had in mind a square painting, a night scene with the oak placed in the center (to pair with an identically composed picture, Swallows at 11am, set in the morning). This canvas had already been prepared with a dark acrylic underpainting. I decided to change the time of day of the scene but used this underpainting because the emotion I now wanted to express had a sense of floating on blackness about it.

After the painting was finished and I had compared it to its finished companion, Swallows at 11am, I decided to call the new painting Swallows at 9pm. The reference to the birds and to time suggests temporal scales at play. At least a year has passed between the two images, as evidenced by the crop rotation, rape following barley. The birds would have migrated to Africa and back. Of course the same 250-year-old oak remains; it offers a very different way of measuring time. There are only a few days in the year when the crop looks like this, only a few minutes in the day when light is like this, only a few seconds to see the birds.

In the ancient Roman world, bird watching was connected to augury. In the end there were four swallows, like little horsemen, and a tiny red light. I think this makes the beauty of the scene both uneasy and somehow more truthful.