Ninety-Nine Bottles of Pee on the Wall

Everyone says they’ve got a book inside, but hundreds of people actually write them—and are preyed upon by scam artists. The greatest story of literary vigilantism ever told.

The first time I peed in a bottle was in the spring of 2006, at a folk concert in Ann Arbor—my brother Peter’s album release party. I was tending bar in the back of a small art space while Peter played for a packed house of friends, family, and local fans, crammed side by side in metal folding chairs. It’s hard to serve drinks without drinking plenty yourself, and by the middle of the show, I desperately had to take a leak. Peter was singing his most earnest, heartfelt tune, and the place was so full, there was no way I could’ve made it to the bathroom without creating a disturbance.

An empty Orange Mango Nantucket Nectars juice bottle in a bin on the floor called to me. Hidden by the bar, I twisted the cap off, popped my zipper, and as slowly and gently as I could, whizzed into the bottle, all the while standing straight and nodding my head to the music. You know how tinkling against the side of the toilet bowl keeps the sound down? I discovered that peeing against the inside of the bottle did the same. The bottle filled just past the top of the label. I was surprised at how hot my pee felt through the glass. I screwed the cap tightly back on, dropped the bottle in a trash can, and just like that the crisis was averted, a swift and easy victimless act. Of course, like speeding or shoplifting, once you see how simple it is to get away with something, there’s nothing to stop you from doing it all the time. On our months-long tours, where each night I’d read Found notes and stories and Peter would play guitar and sing a few songs, I often preferred sleeping outside in the back of our van while my brother crashed on the couches of friends or hospitable strangers. For me, the problem had always been what to do when I woke up in the van after a night of drinking and really had to pee. What had been an empty street at three a.m. could be alive and bustling at a quarter after seven. Now I began to plan ahead, and before I went to sleep, I’d make sure an empty Nantucket Nectars or Odwalla bottle was handy (wide-mouth bottles required less docking precision). At dawn, crouching in the van behind tinted glass, head pressed to the ceiling, I’d fill a bottle—sometimes two, a couple hours apart—and crash right out again. Before we got on the highway to head for the next town, I’d stop at a gas station or a park and slip the bottles into a garbage can, surreptitiously, like condom wrappers at your girlfriend’s parents’ house, or a vandal’s spent cans of spray paint.

Here and there, I began to pee in bottles even under less urgent circumstances. Sometimes, before our Found shows, if there was no bathroom backstage, I’d huddle in the corner and fill an empty water bottle with pee, rather than wade through the crowd, already in their seats waiting for the show to start. The more you do something—even something a bit weird and aberrant—the more normal it becomes to you. Nudists know this, as do bulimics, self-cutters, compulsive hand-washers, scratch-off lottery addicts, and people who masturbate while driving on the interstate. Peter walked in on me a few times backstage, caught me peeing into a bottle, and hissed, “That’s fucking sick, dude,” and I always thought he was the one being unreasonable.

Still, for every bottle I peed in while we were on tour, I took 60 run-of-the-mill leaks in a rest-stop urinal or behind a tree on the side of a country road. Mostly, the bottles were a last resort. And once I got home, I might never have peed in a bottle again if I hadn’t fallen off my friend Mike Kozura’s roof while helping him change out the storm windows for screens. My right ankle was completely shattered, and for a couple of months I was laid up in my bedroom—a hot, sweaty attic lair—feeling like Martin Sheen at the beginning of Apocalypse Now, but with only five-eighths the madness.

The staircase to my room was incredibly narrow and steep, and to descend it to take a leak required 10 minutes of precarious maneuvering. Instead, I began to pee almost exclusively in bottles. I became an expert at it. I knew, for instance, before I peed how much pee was going to come out of me—I could select the right half-filled bottle and fill it right to the top and be done with it, sending it to pasture on the floor behind the TV stand. Not that I meant to start a collection, but there was no easy way to dispose of them. My housemates were happy to bring a pizza upstairs when I ordered for delivery, but wouldn’t have been as gracious, I didn’t think, about carrying out my sloshing portable urinals. And with my useless, throbbing ankle, the thought of fighting my way downstairs and out to the driveway to dump them in the garbage bins felt overwhelming. The funny thing was, years before, I’d heard a story from a friend about a roommate he’d once had who was so lazy, he’d pee in an empty milk jug in his basement bedroom rather than walk upstairs and use the john. At the time, I’d thought that sounded completely nasty, but now my own pee-filled bottles had outgrown their nest behind the TV and began to line the shelves of the towering bookcase at the foot of my bed. I peed in all kinds of bottles, and developed favorite brands—Odwalla, Naked, SoBe, Fuze, and those small, round, glass bottles of apple juice called Martinelli’s, which, dangerously, looked like they contained apple juice even when filled with pee. I began to hoard empty bottles to have on reserve. When my housemates had parties, I’d creep down from the attic at five a.m. after everyone had cleared out and crawl back upstairs with abandoned 40-ounce screw-top bottles of Miller High Life and St. Ides tucked in my armpits.

The more you do something the more normal it becomes to you. Nudists know this, as do bulimics, self-cutters, compulsive hand-washers, scratch-off lottery addicts, and people who masturbate while driving on the interstate.

July Fourth arrived. From my window, I watched little kids running around freely in the park across the street, waving sparklers, peeing wherever they chose, and I cradled my swollen, misshapen ankle, heartsick—the girl I’d been dating on and off for several years and loved dearly, Sarah Locke, had decided to move to Oakland to live with her new boyfriend, an animator and budding art star she’d met on MySpace named Ghostshrimp.

Sarah was a tiny, beautiful punk rock girl who’d grown up on a Sioux reservation in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. She made me soup when I was sick, “answered” bananas like they were a telephone—“Hello? I can’t hear you. Hello?”—and helped me put together each issue of Found magazine in my basement. I’d never been involved with someone so closely or for so long. The night before she left, she stopped by my house to say bye and sat at the foot of my bed. We’d already talked through it all plenty of times, and by now the agony had subsided, and we were full of a love for each other that seemed larger than Ghostshrimp and the brokenness of the present. Sarah marveled at the collection of pee-filled bottles I’d amassed. “It’s absolutely incredible,” she said. “I’ve never seen anything like that.” She sniffed the air. “I can’t believe they don’t smell.” I was ashamed, but also sort of proud, and fascinated with them myself. The range of pee color, in itself, was striking—dark, hornet gold, to pale yellow, to nearly clear. “There must be 50 bottles here,” said Sarah.

“There’s more behind the TV stand,” I confessed.

Sarah said, “Let’s count.” We tallied them up. There were 99. Sarah began to sing, “Ninety-nine bottles of pee on your wall, 99 bottles of pee…” She trailed off. “I can’t believe I’m leaving you,” she said.

I picked up the song, and continued on, sadly: “Take one down, pass it around, 98 bottles of pee...”

Sarah was gone, and all I had was my pee bottles and a ruptured ankle that buzzed with excruciating pain if I brushed it against anything. I was as hobbled as the dude in Misery, but without a number one fan. Besides the sheer effort involved, it seemed to me that to simply bag up all the bottles, a dozen at a time, and crutch my way to the street to toss them out would be squandering a unique and bizarre opportunity. It’s not every day you end up with an arsenal of 99 bottles of pee, and though I wasn’t sure what exactly I might do with this kind of unusual stockpile, my instincts told me I’d somehow find a use for them, as part of a prank or a practical joke, perhaps, or some darker form of mischief.

Stuck in my tiny sweatbox room all summer, I spent hours at a time online, exploring the Internet’s odd, dark reaches and fanciful buttes. I researched how far flying squirrels and flying fish can actually fly, then watched clips of the kidnapped journalist Daniel Pearl’s beheading. I absorbed every beat of each national news story, first on the New York Times site and then on the sites of the local papers where the incident had gone down, enjoying the battles waged in the comments sections, which were often unrelated to the topic at hand, like a discussion—after an article about an armored-truck heist on KCStar.com—of the Royals’ relief-pitching woes. Before long, I was clicking on obscure links sent to me by relatives I barely knew, and reading mass emails I would’ve deleted in an instant in the days before my reverse jackknife off Mike Kozura’s roof.

An email landed in my inbox—“The Times Square Literary Agency Announces ‘Great American Novel’ Writing Contest!”—and I read it carefully through. It looked pretty standard: send us a copy of your book and a $60 reading fee, and if the stars line up right you’ll win a cash prize, along with the promise of agency representation. This particular entreaty had a few weirdly shaped cornices, though. For one, even though the contest was sponsored by the Times Square Literary Agency, the address for submissions was on Mission Street in San Francisco. Also, an awards ceremony was to take place in New York City in just six weeks, hardly enough time to collect all the entries and give a panel of judges an adequate chance to read through them. And another thing seemed strange—the email specified that any book was eligible, fiction or nonfiction, no matter when it had been written or whether it had been published or not. But despite its whiff of fishiness, I forwarded it to a couple of highschool kids I’d met on tour who were aspiring writers, and also to my dad, who’d just self-published a book of autobiographical vignettes called Brooklyn Boy. Then I dropped it into one of my email folders and moved on, probably to watch ‘80s rap videos on YouTube—“Iesha” by Another Bad Creation was a current favorite.

The next night, another email caught my attention—“The Golden Gate Literary Agency Announces ‘The Next Hemingway’ Writing Contest!” The details were identical to those in the previous email, with the same address for submissions, but for this contest the entry fee was eighty-five bucks instead of sixty. I clicked around the Web and discovered a half dozen other “literary agencies” of questionable provenance, all listing the same office address, responsible for a handful of dubious writing contests, including the Golden Typewriter Awards, the Guggenheimer Writers’ Circle Awards, and the O’Henry Awards (different from the esteemed, legit O. Henry Prize). Sketchy, no doubt, but I simply deleted the email and hauled myself up to put Black Knight in the DVD player and pee into a tall, empty Evian bottle that one of my housemates had left behind in the kitchen.

Then, two days later, blooping into my inbox—“Times Square Literary Agency Announces New Contest Categories!” The email explained that their Great American Novel writing contest was expanding from six categories (Mystery, Romance, Science Fiction) to 18, and that they were awarding six prizes in each category instead of just one. The more I poked around, the more I got the sense that someone was blasting out thousands of emails, sounding the call for these shady contests, then sitting back and watching the checks roll in. It was clever, in a sense, maybe ingenious, but over the years I’d always drawn a sharp distinction between hustlers and scam artists. Hustlers: me and the other eleven sad sacks scalping tickets outside a Chicago Blackhawks game in mid-January, freezing our fucking asses off, and heading home with a hundred bucks in our pockets, if we were lucky; or the kid in Albuquerque, say, who used to sell me nickel bags of weed outside the Laundromat at Central and San Mateo. Scam artists: the guys outside Soldier Field before the Rolling Stones concert dealing counterfeits, which are handsome enough to fool the untrained eye but don’t scan at the gate and get turned away; the dude who takes a twenty from you, presses a Ziploc bag of oregano into your hands, and darts off. Hustlers get you what you want at a price you’re willing to pay; the “hustle” is convincing you that you want what we’ve got. Scammers abuse your trust and hang you out to dry—they’re the ones who make things tough for your everyday honest hustler, and among hustlers, no one is more despised.

I read back through all three of the contest emails. It became crystal clear that some piece-of-shit scam artist was preying on aspiring writers just hoping for a wisp of recognition. I considered this an added insult—nobody deserves to be swindled, but it took a particular kind of cruelty to bilk sweet, earnest, well-meaning writers, especially the ones who’d worked hard enough to actually finish a book and were now struggling to get it out there and read by people. Still, the world’s full of hostile scams, as I well knew from the dozen hours a day I was spending online, and in the Internet’s Wild West, I was no sheriff, just a lonely homesteader trying to get by. The question was: What was I going to do about it?

About a week after Sarah left, my dad stopped by my house. A year before, at the age of seventy-one, he’d retired from the University of Michigan Health Service, where for almost three decades he’d managed the janitorial staff and overseen building repairs. He now reveled in his new freedoms, reading books he’d always meant to read, taking theater classes, and writing plays and stories. We’d had a party for him at a local mom-and-pop shop called Nicola’s Books when Brooklyn Boy had come back from the printer’s.

But in retirement, money was tight, and I often got texts from friends who’d seen my dad hustling tickets outside U of M football, basketball, and hockey games, and concerts at Hill Auditorium. I was sitting on my front porch when he pulled up in his ’81 Ford Fairmont, muffler hanging by a rusty tendril, clattering along the pavement, sending up a geyser of pink sparks. He waved and cut the engine and the Fairmont went into its customary death rattle and coughed up a cloud of green smoke. “Check it out!” he said, crossing the street to my house, a wide U.S. Postal Service flat-rate box in his hands. “I got your email. I’m sending Brooklyn Boy to that contest you told me about!”

Scammers abuse your trust and hang you out to dry—they’re the ones who make things tough for your everyday honest hustler, and among hustlers, no one is more despised.

Oh fuck. He gave me a hug and sat next to me. I said to him, “Don’t do it, Dad. It’s my bad. I shouldn’t have sent you that thing. It’s a scam.”

“No it’s not. I went to the worldwide website.” He told me he was sending in four copies of his book, entering four separate contests—the Great American Novel, the Next Hemingway, the Golden Typewriter, and the Tom Wolfe Memorial Challenge. He’d written a check for $265.

We haggled about it for 20 minutes. Here was my dad, 72 years old, who couldn’t afford to get his tailpipe fixed and was on his way to scalp tickets at the Ann Arbor Summer Festival for the gospel group Sweet Honey in the Rock, about to flush a couple hundred bucks down the shitter. But he couldn’t understand why I wasn’t being more supportive. “Maybe they’ll like Brooklyn Boy,” he said forlornly. “You told me it was good.”

“Dude, I’m telling you, it’s just some fucking scam.”

“How do you know?”

“I don’t know. I just know. I mean, Tom Wolfe’s still alive! Why would they have a Memorial Challenge? Look, I’ll see if I can figure out a little more about it, just give me a few days.”

“Today’s the deadline,” he said. “I’m sending this in. I want people to read my book. Finding an agent’s the first step to getting a real publisher.” He turned the package over in his hands, addressed to the Times Square Literary Agency in San Francisco. “I better go. Sweet Honey in the Rock’s an early-arriving crowd.”

I watched my dad drive away, then crutched back into the house and crawled up the stairs to my room. In a fever, I slapped and Googled my way through dozens of websites, trying to peel back the curtain on the Times Square Literary Agency’s sleazy Wizard of Oz. It only took about half an hour to find him—his name was Lon Hackney, an appropriate name for a failed writer, which is what he seemed to be. A film-biz veteran, he’d written a somewhat prescient book in the nineties about Hollywood’s overreliance on stars to deliver blockbusters at the box office, which was largely ignored. Since then, he’d freelanced for a series of dodgy Internet news sites like the Bong Smokers’ Review, published a couple more books through a vanity press, and then, a few years before, had created a series of nationwide music and film conferences which he dubbed “The Future Is Now,” where turnout had been dismal, according to a couple of disgruntled accounts I tracked down from those who’d paid to become sponsors. The writing contests appeared to be his latest concoction—meant, perhaps, to exact revenge on a publishing world he’d found impenetrable, but actually victimizing writers like himself. I could hardly think of a more cynical, mean-spirited swindle. To be fair, I knew it was possible that I was only jumping to conclusions. In a couple of online interviews, he spoke earnestly about the role of independent literary agents in helping new authors gain exposure. Reading between the lines, though, I could smell the bullshit.

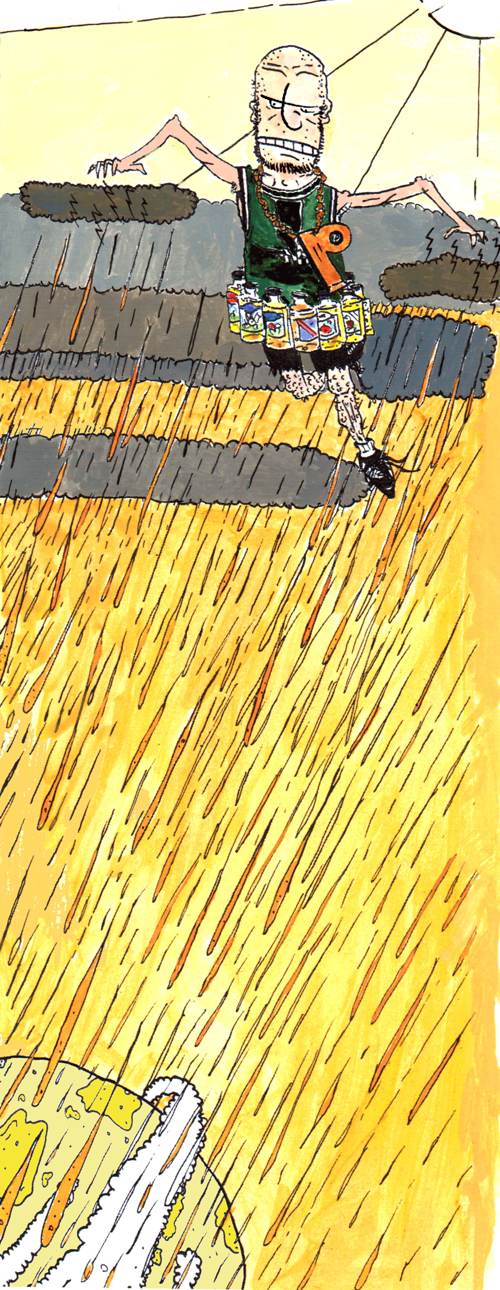

Night had fallen. I looked up from my laptop, and in the darkness of my room, quietly humming, stood more than a hundred bottles of pee, proudly at attention, like soldiers ready to be shipped off to battle. In an odd, deranged trance, I tucked four bottles into a plastic grocery bag, put the bag inside my backpack, strapped it on, and scooted awkwardly downstairs, keeping my swollen ankle raised high. I pulled myself across the floor of the kitchen and down to the dank basement where I have my Found office. It’s a true fact that at the University of Michigan I lived in the same exact dorm room on Prescott Hall in East Quad that had been inhabited thirty years before by a student named Theodore Kaczynski, who became the Unabomber. No doubt I was channeling a bit of old Kaczynski’s rage and maniacal righteousness as I composed a six-page handwritten letter to Lon Hackney, lambasting him for being such a fraud. I signed it, “A Concerned Citizen.” Finally, I cracked the folds on a USPS flat-rate box, placed the bottles of pee inside, and stuffed it with Styrofoam packing peanuts to keep the bottles in place and make sure they didn’t pop open in transit. I folded my letter and squeezed it into the box.

Before I sealed it up, though, I second-guessed myself. I remembered a story I’d heard from a scalping pal of mine in Chicago who went by the name of Lobster. Lobster had told me about something this dude called Thirty-fifth Street Frankie—who I’d met a few times—had once felt compelled to do. Some guy owed Frankie eight grand—maybe for tickets, maybe a gambling debt, who knows—and he kept laughing it off whenever Frankie levied a threat. At last, Frankie hired four giant Southside thugs (friends of his, probably) to take care of the matter. One night when the guy came home from the bar, they grabbed him outside of his apartment, tied his hands behind his back, blindfolded him, shoved him into the trunk of a Lincoln, drove him up to Wisconsin, and left the car deep in the woods for two days. Then they drove him back to Chicago and dropped him off in the same alley they’d snatched him from, still tied up and wearing the blindfold but without a scratch. All they said, before roaring off in the Lincoln, was, “Hey, buddy, fly right.”

“Can you imagine?” Lobster had said to me. “Two days in the trunk of a car, literally shitting yourself, not sure if you’re going to live, and the whole time wondering who you wronged. And the message wasn’t ‘Pay Frankie,’ it was ‘Fly right.’ He might’ve guessed it was Frankie, but he probably had debts all over town. Frankie got his money the next week.”

I had no idea how true Lobster’s story was, but something about it was inspiring. Down in my basement, reading over my long, chicken-scratched letter to Lon, I realized there would be something splendidly ominous in sending him the bottles of pee without any note of ordinary, petty complaint. Most likely, he’d just shrug off my criticisms and tear the note up. Instead, why not let him be haunted, like the dude in the trunk of the Lincoln, led to a deeper reflection of who might be angry with him, and why? I ripped up my Kaczynski letter and with a black ballpoint pen carved a new note, tracing the words 50 times over: “FLY RIGHT.”

The next day, I drove 40 minutes south on M-23 and mailed the box from a post office in Toledo, Ohio.

That was only the first shot fired. As August edged in and the dog days of summer wore on, I packaged up fresh pee bottles every two or three days and cruised around Lower Michigan, northern Ohio, and northern Indiana, left foot on the pedals, right foot up on the dash in a bag of ice, scouting post offices and mailing packages. I preferred post offices with an automated scale in the lobby so I could pay the flat-rate postage and drop my box through the parcel slot without coming face-to-face with any postal clerks. Then I’d crutch it back to the van and blast tunes on my triumphant drive home, flush with adrenaline, like George McFly in Back to the Future after finally punching out his nemesis, Biff. I may have been a brokenhearted writer blowing $9.85 to mail his own urine to California, but I felt like a fucking cowboy, a vigilante, rolling into town on my steed to dole out my own brand of frontier justice. I never fully lost track of just how psychotic all of this would’ve seemed to anyone else, so as with most weird, fucked-up things you find yourself doing in life, I kept these outings a secret. But to me, at the time, it all made sense. It even seemed courageous and noble. I was just trying to make America right again.

In response, seemingly, the emails from Lon Hackney’s phony contests intensified. “Great American Novel Deadline Extended!” “Reserve Your Gold-Area Booth For The Golden Typewriter Awards Gala!” “Tom Wolfe Memorial Challenge Now Accepting Submissions in 12 Languages!” I’d lie in bed sweating, gulping mouthfuls of Advil to keep my ankle from throbbing, and growing more and more incensed at Hackney’s bold, unapologetic deceits. At last, I’d haul myself to the basement and compose short, blunt grenades of condemnation, writing with my left hand to disguise my scrawl: “STOP IT LON,” “NO MORE CONTESTS,” “GET RICH? DIE TRYING.” One night, sealing pee bottles into one of the flat-rate boxes, I cut my hand on its sharp, gummed edge, and went ahead and smeared blood all over my note before tucking it inside. I was half Travis Bickle, half Jimmy Stewart from Rear Window—laid up, certain I was witness to a troubling crime, but unable to do much about it or get anyone to pay attention.

One weekend in late August, just to get outside, I crutched across Wheeler Park to a house party on Main Street and drank a pint of Maker’s by myself, watching young punk drifters twirl fire in the yard. Wasted, I called Sarah in the East Bay. “Oh my God, are you okay?” she said. “Your voice sounds really weird. Not just drunk, but weird. Are you crying?” I tried to explain my battles with Lon Hackney, but I’d drunkenly conflated Hackney with Sarah’s new boyfriend, Ghostshrimp, and I kept saying one name when I meant to say the other. In a certain sense, they’d merged in my mind, even when I was sober—not only was Hackney robbing from the poor to give to himself, it sometimes seemed to me, he’d stolen my girl, too. “I can’t talk to you when you’re like this,” said Sarah. “I’m hanging up now.”

I made it home, dragged myself up to my room, opened a bottle of water, and took a long, mighty swig—but it wasn’t water, it was my own goddamn pee. Even through my rigorous drunkenness, the taste was horrendously, mind-meltingly sour. I gagged and spit out what I could into the trash can, accidentally leaning my weight onto my useless right foot. A bolt of hot pain lanced up my leg and I crashed to the floor, crying to myself, full of sorrow and self-pity. I desperately had to get the taste of pee out of my mouth, but the only thing within reach was a small carton of blue Play-Doh that I’d bought as a gift for my nephew. In utter defeat, I clawed loose a couple of doughy chunks and chewed on them until I passed out.

Late one night, a new page appeared on the Times Square Literary Agency website, an overview of a conference Lon Hackney had put together in San Francisco the previous summer called “The Future Is Now”—apparently he’d been recycling the name from previous scams. This new conference featured an awards ceremony where authors were invited to read from their work (and rent vendors’ booths for a hefty fee). Twenty thousand people had attended the day-long event in Golden Gate Park, Hackney boasted. He’d posted a dozen pictures, perhaps to try to legitimize the festival in the minds of any doubters—especially, I figured, his pee-bottle provocateur. In the photos, folks read from self-published books in front of a tiny bandshell to a half dozen people seated in folding chairs, while joggers, rollerbladers, tourists, and young mothers with strollers sidled past without a glance. Twenty or thirty folding tables had been erected haphazardly across a concrete plaza, and authors hovered behind them with stacks of their own books, lonely as Yankee Stadium ice cream vendors during an April snow squall. Yellow, blue, and green balloons clung to trees in sad clumps, draped with wet streamers, and amid the gloom, a woman dressed as a clown, wearing a blue Afro wig and face paint, stood picking her nose. If Hackney’s intent in posting the pictures had been to lend credibility and glamour to his writing contests and their associated events, he’d failed miserably.

I noticed in one photo a young, pretty woman seated behind a table stacked with books, which I presumed she’d written, holding up a copy, and smiling wanly. Her name was visible on the book’s cover—Ondrea Wales—and after a quick Google search, I found my way to her website. She’d written three teen novels for a major publisher, and in her author photo looked confident and bright. I dropped her an email: Investigating Lon Hackney and “Future Is Now” conferences. Please call. My phone rang the next night—Ondrea.

“It was one of the most humiliating days of my life,” she told me. “I’d been hearing from so many people that these days publishers don’t have the resources they used to, that if you want your book to get out there, you have to do it yourself. I paid five hundred dollars for that table, and sold two books the whole day. It was a disaster.” Ondrea told me that she was the only one there who hadn’t self-published their book or put it out through a vanity press. The most embarrassing moment of her day was when an editor from another publishing house had wandered by and stopped to chat. “She was aghast that I was out there—she thought my publisher had set it up. I confessed that I’d set it up myself, and she just kind of smiled at me like I was a crazy person and walked away. I felt duped. I felt lied to. The whole thing had been misrepresented to me in every way.”

She got a little upset, just thinking back on it all, but her voice was sweet, even silky, and as we talked on, I gazed at Ondrea’s author photo on her website, aware of the beginnings of a crush, the tips of my fingers tingling. I asked her if she felt so out of place simply because she was an established author surrounded by self-published folks, and she said no, that wasn’t it. “It’s not that I didn’t belong there because I thought I was better than the other authors,” she said. “It’s because nobody belonged there. The awards gala was a joke. Everybody was disappointed.” A conference aimed toward self-published authors could still be dignified and inspiring, she said, but this one lacked even the slightest semblance of anybody’s effort or care. No press, no promotion. People had come from all over the country, only to get up on stage and read for ten minutes to a crowd of three. Twenty thousand people? There might’ve been twenty thousand people in Golden Gate Park that day, she said, but there were never more than a couple dozen at the bandshell. Ondrea lived in New York City, and she’d flown to San Francisco to participate. One guy she’d met, a children’s book writer, had traveled all the way from Belgium. “He was really disconsolate,” Ondrea said. “But he—and all of us—tried to put on a brave face, at least till we got home. Who wants to admit that they’ve been scammed?”

We talked for another 45 minutes, the longest conversation I’d had with anyone since Sarah had left for California. Ondrea was likable, upbeat, thoughtful, and perceptive, and apparently a fairly successful writer with a healthy dose of talent—the kind of girl I often fantasized about meeting. I thought of Lon Hackney, that piece of shit, and my swollen ankle pulsed and throbbed. It was one thing to gyp my dad for a couple hundred bucks, it was another to put sweet, darling Ondrea Wales through a day of hellish awkwardness and shame.

“How’d you get interested in all of this, anyway?” asked Ondrea, a flirtatious note of curiosity creeping into her voice. I told her my dad had been suckered in, and explained that I’d been sending hate mail to Lon Hackney, without mentioning any specifics.

“I met Lon,” she said.

My ears perked up. “Yeah? What was he like?” I hadn’t been able to find any pictures of him online, I told her.

“He was—and look, I don’t have anything against fat people—but he was a fat, sweaty slob.”

I laughed nervously. My bedroom was as hot as a sauna, and I was sticky with sweat; I hadn’t showered in a week and hadn’t shaved in two. “Really?” I squeaked.

“Yeah,” said Ondrea. “He could tell I was on to him, and he avoided me the whole day.”

“He’s got to be stopped,” I said. “Listen. Ondrea. I’m gonna stop him.”

“Yes, Davy!” she cooed. “My hero.”

I flew to San Francisco. It was November, and I could walk again, sort of, but only short distances and with great pain. My mission was twofold—visit Sarah and beg her to come home with me to Michigan, and confront Lon Hackney and dump a bottle of pee on his head. That was my actual plan—to dump pee on his head, and let him know that I was doing it in the name of all the writers he’d ever fucked over.

I’d thought I would surprise Sarah, but when I called to tell her I was in the Bay Area for a week, she told me she was camping with Ghostshrimp in the Redwoods and wouldn’t be back for five days. While I waited for her to return, I turned my focus to stalking Lon Hackney. His office was just a few blocks from my friend Eli’s apartment in the Lower Mission, where I was staying. I shuffled my way over around three in the morning after a long night with Eli at the Peacock Bar, just to scout things out.

The headquarters of the Times Square Literary Agency (and Lon’s entire trick deck of business ventures) were housed, I discovered, in a single dingy office among a block of six others above a liquor store and a tanning salon. A flight of exposed concrete steps led upstairs from the parking lot to an outdoor T-shaped corridor, with a row of office doors on either side, numbered with faded stickers from a hardware store. I found Suite #4. After all those months of sending flat-rate boxes to the address on Mission Street, it was a rush to actually be there, outside the door where my pee bottles had been delivered. The shades were drawn, and for all I knew nobody had been there in months, though a handwritten label remained affixed to the mail slot that said: LH LITERARY SERVICES/FUTURE IS NOW—Lon’s umbrella groups. The mail slot’s inside duct kept me from spying into the room, but I was able to peek down at the floor, where a mid-sized pile of manila envelopes and bubble-wrapped packages lay spread on the worn carpet, like a Christmas haul prepped by elves from Staples. I could read a few of the return addresses—Guymon, Oklahoma; Key West, Florida; Regina, Saskatchewan—enough to confirm the reach of Lon’s operation. It was late, I’d had plenty to drink, and I had to pee, but had no bottle to piss in. I looked around to make sure I was alone, unzipped, and peed straight onto the door of Lon’s office—one of the most enormously pleasing whizzes I’d ever taken. Then I headed back to Eli’s place.

It gave me an evil thrill to picture him arriving at his office and finding my bottles waiting for him, creepy as tarantulas, announcing my arrival in California.

Over the next few days, I visited Lon’s offices a dozen times, hoping to cross paths with him. In a plastic bag, I carried three bottles of pee in Vitamin Water bottles in case we met face-to-face. I tried to imagine how he might respond as I doused him—would he run? Would he fight? But as the days passed with no sign of him, I began to fear that his office visits were few and far between. Maybe he’d glimpsed me from the parking lot, lingering outside his office door, and had known to stay away. Mail accumulated on the floor of his office. My pee bottles were too big to fit through the mail slot, but one night I left one wedged between the knob of his office door and the door jamb, and another balanced atop it. It was one thing for him to receive pee bottles in the mail—deranged threats shipped from the Midwest—but it gave me an evil thrill to picture him arriving at his office and finding my bottles waiting for him, creepy as tarantulas, announcing my arrival in California.

When I showed up the next morning, I saw that the bottles were gone, and my heart flim-flammed at the idea that he’d returned to his post, and was in there, on the other side of the door. But his office was dark, and through the mail slot, I saw that all the packages were still heaped on the floor. Most likely, the bottles had been chucked out by the old Bangladeshi woman who owned the building and ran the liquor store below, or her teenage grandson, who halfheartedly swept the parking lot every day at dawn and at dusk. I’d asked them one afternoon about Lon, telling them he was an old friend I was trying to get in touch with, but they’d noticed me skulking about gimpily the past few days and seemed to sense my darker intentions. After conferring in Bengali, the grandson turned back to me and said, “Sorry, boss, we don’t see him much. But I got you a case of those Orange Mango Nantucket Nectars you were asking about.”

Sarah returned from her camping trip and called me, and we made plans to hang out the next day. “What do you want to do?” she said. “Go to bookstores? See a movie? You ever been to the Cartoon Art Museum?”

“I need your help,” I told her. “It’s a stakeout.”

Sarah brought disguises—a tiger mask for her, glasses-with-giant-nose-and-bushy-mustache for me. We sat for hours on a pair of overturned buckets in the alleyway beside the liquor store, within sight of the cement steps from the parking lot to the offices upstairs. Anytime someone disappeared up the steps, Sarah raced over, tiptoed after them, then emerged a minute later, shaking her head: “Not our guy.” We played Go Fish, worked on Word Search puzzles from a gigantic book, filled out Mad Libs, and munched wasabi nuts, while I drank mango juice and a half pint of R & R whiskey, and Sarah sipped a jug of chocolate milk through a tiny straw. I was still in love with her, and told her so plenty of times over the course of the afternoon, and she found ways to politely deflect my advances without making me feel too crummy. She even tolerated me squeezing her knee, kissing her ears, and resting my head on her shoulder. “Come back to Michigan,” I said, my voice crackling with emotion. “Let’s just try this one more time. Come home, Sarah.”

She jumped to her feet. “Did you see that? The mailman! He’ll know something.” She dashed across the alley and up the stairs. I waited, hunched on my bucket, swirled in the hot shrieks and honks of rush-hour traffic. When she came back, she told me what the mailman had said: he’d met Lon once or twice but almost never saw him in the office. Often, packages arrived that were too big to fit through the mail slot, and he’d leave them for Lon with the accountants in Suite #6. “I knocked on their door,” Sarah said. “I thought they might know when he’d be back. But they already left for the day.”

“You’re really not gonna come back home with me?” I asked her.

“I can’t,” she said. “I love you, but I’m happy out here, I’m happy with Ghostshrimp. We’ve got Keenan and Banksy”—their dog—“we’ve got the apricot trees, we’ve got the Draweteria.” This was their daily art project where Ghostshrimp whipped up illustrations and Sarah colored them in; they sold the results on his website, often for hundreds of dollars. “Don’t cry,” she said, putting her arms around me. “Everything’ll be okay.”

“I’ve got to take a leak,” I said, my heart twisting. “I’ll be right back.” I scooped up my empty half-pint R & R flask and limped up the steps to Lon’s office door. Lights were on in some of the adjacent offices, but I was slightly buzzed and by that point of my West Coast visit no longer gave a fuck—I dropped trou and filled the slender liquor bottle with pee. Someone poked their head out of a door and quickly slammed it shut. A moment later, the Bangladeshi woman from the liquor store came rushing up the steps, shouting at me and waving a cordless telephone. “I’m calling the 911!” she shouted. “Police come. It’s ringing right now! You must go. You must go.”

“Okay, okay,” I shouted back, buttoning my pants, feeling like a mutant superhero who has only good intentions but is generally viewed as a freak. Quickly, I tightened the cap on the bottle and launched it through the mail slot into Lon’s office. I rushed past the old woman, my ankle flaring with pain.

“Don’t come back here!” she hollered after me. “Only for office workers and their guests. Want to go to jail? No thieves allowed!” A fuse lit within me. I turned and exploded on her: “Thieves? Lon Hackney’s the thief! Your tenant, Lon Hackney. A criminal! You’re harboring criminals here. You’re sheltering an extortionist. You’re complicit! Look, I’m a fucking police officer. Want me to call the FBI?”

She looked at me tiredly, unimpressed by my wild, nonsensical lies and impotent threats. For a police officer, I supposed, the glasses-nose-and-mustache disguise lacked a certain aura of professionalism. I tugged the rig off my face. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I fell off a roof and things have been really hard for me lately. I like your liquor store. I think it’s cool that you guys sell stamps. No one sells stamps anymore. And you have a really nice grandson.”

“Thank you,” she said, dropping her hands to her side. “I didn’t really call the 911. But I guess it is time for us to say goodbye. You can find another place to be yourself.”

Sarah walked me back to Eli’s apartment. My flight was early the next morning. “Text me when you land in Detroit,” she said, “so I know you made it home safe.”

At 6:30 a.m., on the way to SFO Airport, I convinced Eli to shoot past Lon’s office on Mission Street one last time. I’d written a note to slip through his mail slot, to go with the bottle of pee from the evening before, half veiled threat, half last-ditch appeal to his conscience: “WE'RE WATCHING EVERYTHING YOU DO. DO THE RIGHT THING.” But when I got to his office door and poked open the mail slot, I was stunned to see that the pile of mail on the floor was gone. I heard myself say out loud, “What the fuck?” Sometime during the night, apparently, Lon Hackney, stealthy as a ghost, had flitted through, collected two weeks’ worth of contest submissions—or at least the checks from each package—and disappeared again into his bunker. After a week spent staking out his office, I couldn’t believe he’d spirited past me, that I’d missed him by hours. Still, it meant he’d found the bottle I’d left for him, and that thought alone—the eel of spooky unease I was sure now circulated in his belly—kept me smiling the whole way home.

Ten months passed. Lon seemed to be lying low. Had my efforts huffed and puffed and blown his house of cards right down? It was hard to say, but all of his lit agency emails slipped to a trickle and then fell off completely. Maybe he’d found a new racket, I imagined, and was sticking people with balloon-payment mortgages, or peddling shady investments, or running a three-card monte game on Fisherman’s Wharf—nothing to be proud of, to be certain, but all fine by me. One Saturday in the fall, a guy left his Chevy Silverado parked in front of my house, with Ohio plates and swathed in Ohio State Buckeyes bumper stickers, and I gifted him my remaining bottles of pee in the bed of his truck, with a note that said, “GO BLUE.” I spent the winter in Michigan, trying to regain strength in my ankle, with mixed success, and talking to girls at the bar, trying to forget about Sarah, with no success.

In the spring, out of nowhere, I got an email from Lon—not a personal email, but the standard call for submissions for his latest writing contest, the Noble Pen Awards. The bastard was back, and I saw that after his brief hibernation, he’d snaked his greedy paws to every corner of the country, expanding his empire from six bogus literary agencies to twelve, each scheduled to host an awards gala at a slew of far-flung “Future Is Now” conferences, beginning with New York City and proceeding westward. Among other contests, he’d christened his newly hatched brood the Golden Pencil Awards, the QWERTYUIOP Quest (okay, that one was clever), and, with what was starting to feel more like ill will than inattention to detail, the Cormac McCarthy Memorial Challenge. What the hell? Couldn’t he at least pick writers who’d already died? I forwarded his email to Ondrea Wales, whom I’d continued to trade messages with here and there, and she wrote back four minutes later: “Oh no! He must be stopped. Come to New York—let’s vanquish him!”

Middle of June, I flew to New York, the weekend of the Noble Pen Awards and Lon’s sham “Future Is Now” conference. I claimed to Ondrea that I had other business there, and I guess I sort of did, but mostly I just wanted to meet her in person and dump pee on Lon Hackney’s head. The conference was now spread over two days—an awards ceremony on Thursday night at the swanky Emerald Bell Hotel, and outdoor readings in Tompkins Square Park the following afternoon. Me and Ondrea made a dinner date for Thursday evening, with plans to head over to the Emerald Bell afterwards to confront Lon.

At five o’clock Thursday, I showered and shaved at my cousin’s apartment in Midtown, and transferred a pair of wide-mouth Aquafina bottles to my backpack from the gym bag I’d brought from home and checked on the plane. The blue, plastic tint of the bottles gave the pee sloshing inside them a greenish, radioactive glow. In the subway station, on the way to meet Ondrea at a sushi place she’d picked out, a police dog eyed me with grim disapproval, as though it sensed I had a bomb in my bag.

In person, Ondrea was even prettier than her picture. She had long blond hair, green eyes, rosy cheeks, and a wide, easy smile, and she wore a white lace top and a purple beret that seemed fashionable, not pretentious. The fact that she’d applied gloss to her lips and a trace of eyeliner—and were those sparkles dusted across her cheeks?—reassured me that I wasn’t crazy for thinking of this as a date, even though in my emails and texts I’d held back from any romantic innuendo and had said only, “Let’s grab a bite,” and, “It’ll be great to hang out.”

What can I say? Ondrea was smart, funny, and inquisitive, entertainingly opinionated, endlessly adorable. For two hours, we tossed back tuna rolls and pounded sake. We talked about writing, our families, our childhoods, our friends, our fears, our hopes, our dreams. I told Ondrea about the old, beautiful, abandoned movie theater with a glorious marquee I’d spotted in the town of Tres Piedras, New Mexico, and how I wanted to move there, fix the place up, and share my favorite movies a couple of nights a week with the locals and whatever road-tripping folks found their way in. Ondrea said she had relatives on her mother’s side who lived in a giant, dilapidated castle in the Slovakian countryside, a hundred miles outside of Bratislava, and had offered to put her up while she worked on her next book. We lapsed into silence, gazing at each other, pondering a home-and-home series: Slovakia, New Mexico.

I ordered another carafe of sake and turned the conversation to Lon Hackney and our impending collision with him at the Emerald Bell, which stirred me with a kind of open-dammed bloodlust. Ondrea wanted to know what our plan would be when we confronted him, and I patted my backpack, on the chair between us, and told her not to worry, I had the whole thing figured out.

I took her hand, and she pulled away to adjust her purse, then reached for my hand again. My heart felt buoyant, hyper-oxygenated. It was the most exquisite of gentle June nights.

“What do you have in there, a gun?” she asked.

I laughed cryptically. “Lon will not forget what happens tonight,” I promised her. “It will haunt him. As long as he keeps it up with all the contest bullshit, this night will haunt him.”

“Cheers to that,” she said. She lifted her sake, and we clinked glasses and downed our drinks. I filled our cups again, and again we downed them. “Might as well finish this stuff off,” she said, with the cutest of shrugs. She poured the rest into our cups and we knocked them back, like a couple of college freshmen on spring break, shooting tequila on Bourbon Street. Ondrea giggled. “I have to pee,” she said. “I’ll be right back.”

“Okay. I’ll get the check.”

We headed for the Emerald Bell, walking cross-town. I took her hand, and she pulled away to adjust her purse, then reached for my hand again. My heart felt buoyant, hyper-oxygenated. It was the most exquisite of gentle June nights in Manhattan. Taxis flared past; the smell of kabobs and sugary roasted almonds wafted from street vendors’ carts; snatches of conversations fluttered through the air from other passersby in Greek, Mandarin, and Jamaican patois. There’s no city on Earth I’d rather walk through filled with drink and holding a girl’s hand. Even my bad ankle, for the first time in a year, felt brand-new.

Outside the Emerald Bell, Ondrea said, “Okay, seriously, what’s our plan gonna be?”

“We’re gonna ambush him,” I said.

“With weapons?”

“Kind of, yes. I brought one for you, too.” I pulled my backpack

off, then thought twice before reaching inside, wondering if my urine bottles were too much to reveal on a first date.

Ondrea saw me hemming and hawing. “What’s going on?” she said, laughing. “What’s in the bag?”

I thought about how humiliated Ondrea told me she’d been in Golden Gate Park the day she’d set up her booth, about her anger at a guy who would take advantage of struggling writers, folks who had the least money to burn. It was what made a pee-bottle attack so appropriate—we’d be fighting fire with fire, lashing him back with the shame he’d splashed remorselessly on so many others.

I pulled out the Aquafina bottles and shook them up, green brew bubbling like a magic elixir. “This is gonna be the night I’ve been waiting for for a long-ass time,” I told her. “We’re gonna give Lon an extremely memorable shower in front of everybody. In the middle of the awards ceremony.” I passed her one of the bottles. “Are you down or what?”

“What’s in these?” she asked. “Well. It’s pee.”

“Pee?”

“Like, urine.”

“Your pee?”

“Yeah, I filled these,” I said, with drunken pride.

“Tonight?”

“In Michigan.”

She stared at me. “Oh my God,” she said. She seemed to recognize my plan’s sinister brilliance.

“We’ll dump these on his head,” I went on, light-headed, filled with glee. “You first, me first, at the same time, it doesn’t matter. We’ll let him know what we think of his scams. We’ll let everyone know. Then—and this is just my suggestion—we should walk up to Central Park and climb in one of those horse-and-buggies, and kiss each other for like an hour and forty-five minutes. I really can’t wait to kiss you.”

Ondrea peered at me, her face frozen into the most curious expression. Over the course of the next couple of seconds, I swear I saw each tiny muscle fiber in her face—from her eyelids to her nostrils to her jaw—drop, one by one, like coins in the Plinko game on The Price Is Right, until she’d reached a look of confused, horrified revulsion. A dagger of instant regret gutted my insides, and I felt all the hopefulness and joy gush out of me, like a gooey knot of intestines.

“No,” she said. “No! I don’t think that’s a good idea at all.” She looked at the pee bottle she was clutching with trembling, fearful disgust, like an accident victim coming off morphine, discovering a hook where her hand used to be. “You don’t even know me!” she cried. “I’m seeing someone right now. I’ve been seeing someone. Did you think this was—oh my God, take this from me!” She thrust the bottle back into my hand.

“I was kidding?” I said, feeling a great sadness rush in. “This is just lemonade. But Lon, he’ll think it’s pee!”

“It looks like pee,” she said.

“That’s the genius of it!”

“It’s pee. Am I right? It’s pee!”

“Okay, it’s pee—but doesn’t he deserve pee? A lot of pee? We’re letting him off easy here!”

Two young West African bellhops, in their trussed-up, tasseled attire, heard our commotion and came trotting near. “Everything okay here?” one of them asked.

“It’s fine, thanks,” I said. “Except she’s breaking up with me.” He looked at Ondrea.

“Everything okay, miss?”

She nodded, but retained her look of distress.

“You two guests of the hotel?” asked the bellhop. His cohort headed away to unload luggage from the trunk of a town car. I shook my head. “Just here for the Future Is Now conference.”

“Oh, cool, man. You guys authors?”

“Yeah.”

“What kind of stuff ? Biographies?”

“Well, this is Ondrea Wales, she writes teen novels. They’re really good—I mean, I think older readers get something out of them, too. Girl of the Century, check that one out, it’s awesome.”

Ondrea’s withering gaze softened. “You read Girl of the Century?” she peeped.

“I read all your books.”

She smiled despite herself, and looked away.

The bellhop edged between us. “Well, if you know anyone who writes biographies, if they want a crazy life story, I know someone they should write about.”

“Who’s that?”

“Me!” For the next several minutes, while Ondrea stood with her arms crossed, sighing and scowling, the guy outlined the strange, unexpected turns that his life and career path had taken, from a nickel mine east of Dakar to a falafel shop in Hamburg to the bellhop stand at the Emerald Bell Hotel near Times Square. His partner kept shouting for him, urging him to get back to work, to which he’d holler back in French, “Deux minutes! Deux minutes!” I tried to gauge Ondrea’s mood—on the one hand, she seemed to think I was a fucking psycho, on the other hand, she hadn’t left yet. Finally, me and the bellhop traded cell-phone numbers and shook hands, and he hurried off. I realized I was still holding the pee bottles, and quickly stuffed them deep into my backpack.

I reached for Ondrea’s shoulder and she shied away. “What do you think?” I said hopefully. “Come on. Time to get Lon?”

She looked at me for a couple of seconds, her clear, green eyes widening. It still felt like anything could happen. At last, she took a sharp breath and said, “I don’t think so. I’m late somewhere. I should go.” She took a step back. “It was great meeting you, though. Good luck in there.”

The air whooshed out of me. “I’ll text you how it goes.”

“Do that,” she said.

“I’m here all weekend,” I said. “I mean, if you want to hang out another night.”

“Okay. Text me.” She turned and headed off down 44th Street, without a handshake, a hug, or even a high five. Then, a half block down, she glanced back at me over her shoulder and flashed a warm, genuine smile, the kind of knowing, intimate smile that, an hour before, I’d imagined she might have had on her face after a long lovemaking session at our castle outside Bratislava.

“I’m gonna get Lon for you!” I shouted, but already she’d flagged a cab and was hopping in. The light at Fifth Avenue slipped from red to green and the cab shot away and Ondrea was gone.

“Oh. Yeah. The Future Is Now,” said a guy at the hotel’s front desk. “They’re in the Legacy Ballroom. Fourth floor. You can take the elevator or you can take the stairs.”

I took the stairs, grand and winding, floating up them three at a time, around and around the lobby’s enormous atrium, gazing at the magnificent, six-story crystal chandelier in the center, sparkling like a frozen waterfall. The steps were layered with thick, luxurious carpet and my shoes made no sound. I felt an assassin’s sense of raw fury mingled with quiet, pulsing determination. It was eight thirty, and the Noble Pen awards ceremony had been slated to begin at eight. Outside the giant oak doors to the conference room, I slid my backpack around and rocked it front-pack style, tugging the zipper open; the tips of my Aquafina pee bottles quivered in the heavy, massive silence. I hauled on the doors and slipped in.

The Legacy Ballroom, for all its lofty name, turned out to be a drab and gloomy low-ceilinged hallway in the shape of three batting cages strung together end to end. About thirty-five men and women in their early fifties to mid-seventies, clothed in rumpled suits and faded dresses bearing Hello, My Name Is name tags, sipped wine from Dixie cups and milled aimlessly along a row of tables, where red plastic plates of carrots, celery, grape tomatoes, and cubes of cheese had been laid out, along with bowls of Chex Mix, a few boxes of Ritz crackers, and loose packets of ranch dressing. It was like a Super Bowl party for homeless academics.

Fucking Lon. He was an apparition, a wisp of smoke—Sasquatch and Keyser Söze rolled into one.

“Excuse me,” said a perturbed-looking woman with long strands of gray hair, grasping my arm. “Are you Lon?”

“No,” I said. “I’m here to look for Lon.”

She called to an older man a few feet away. “Come here, honey,” she said, waggling a finger toward me, “I think I found Lon.”

The man creaked near and offered his hand. “Lon? Pleased to meet ya. When’s the ceremony start?”

I shook his hand. “Thanks. Not Lon, though. Thanks.”

“What say?”

“I’m not Lon!” I quickly apologized, feeling bad for lashing out at the very people I was there to defend. I’d just rarely been so amped up.

“Well, who’s in charge here?” said the man. He turned to his wife. “He says he’s not Lon.”

She looked at me. “You sure you’re not Lon?”

“Fucking positive.”

She gave an exasperated sigh. “Well, ain’t this a fine mess.” It only took a few minutes of poking around, talking to people, to piece things together. The “awards ceremony” was hardly a ceremony at all. According to an old woman in a wheelchair who said she’d been stationed there since six o’clock, a giant, hairy, lumpy guy had shown up around six fifteen, carted in a stack of chairs, set up some tables, and spread out the food and drinks, along with the blank name tags, a couple of markers, Future Is Now pins, and certificates for each of the prize winners. He talked to almost no one and was out of there before seven. The old woman had assumed he was a hotel employee, but when I suggested it might have been Lon, the director of the festival, she said yes, that sounded right, she’d heard someone use that name with him.

Fucking Lon. He was an apparition, a wisp of smoke—Sasquatch and Keyser Söze rolled into one. I’d been to both coasts to track him down and still he kept eluding me. I roamed the hall, chatting up one kind soul after another, trying to get a line on our mystery man, but they were all as mystified as I was. For the most part, everyone’s spirits were up—this was a celebration, after all, and whoever they spoke to, mutual congratulations were in order (they’d all been named prize winners)—but beneath their joviality, a creeping sense that all was not right had begun to seep into the room like a rank smell. And this was just the beginning, I knew. The next day, in Tompkins Square Park, the full extent of Lon’s con would slowly become clear.

Another woman stopped me to ask if I was Lon. “I want to switch booth locations for tomorrow,” she said. “I’m in the Self Help tent, but I asked for Romance.”

I couldn’t bear another second of this. I’d fucked things up with Ondrea, I’d fucked things up with Sarah, and Lon Hackney, I figured, was off counting his riches somewhere, laughing at me and his legion of Noble Pen suckers.

“Well, if you’re not Lon,” said the woman, “you must be an author. What kind of books do you write?”

“Biographies of bellhops.” I was fuming, and trying to sort out my next move.

“Neat.” She reached into her shoulder bag. “Hey, would you like a copy of my novel? I’d like to give you one. I can sign it for you.”

My dad, I knew, if he was in the room, would have been reduced to the same—traveling to New York with hopes of making some publishing contacts, landing an agent, and finding the right home for his book, and before long, feeling lucky just to find a stranger generous enough to accept a free copy.

The woman’s book was called Aiden’s Quest; it was spiral bound, with a sheet of cellophane over the cover, and had been printed at a Kinko’s near her home in Bemidji, Minnesota, she told me. She described it as a ninth-century romantic thriller about a faerie held captive on a Scottish isle and the young monk who fights to free her. “What’s your name?” she asked, peeling to the title page to write an inscription.

“You know,” I said, “would you mind signing it to Sarah?”

“Who’s Sarah?”

“My wife.”

She gave a little squeal, and said, “I’d be happy to. Sarah with an ‘h’?”

“Sarah with an ‘h.’ ”

She signed her book carefully and handed it over, and I thanked her sincerely. Another author approached, offering me a copy of his book, and within a few minutes I’d collected a half dozen freebies before I beat it for the door. I felt my emotions crashing and burning—things with Ondrea were ruined, Lon had blue-balled my pee-bottle siege, and all that was left to do was find a bar and get smashed.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to go far. A half-level below the Emerald Bell’s lobby was a hotel bar called Maroon. I sat on a stool and ordered a Booker’s on the rocks and watched the NBA Finals with two middle-aged Orlando Magic fans who said they were Nextel salesmen from Kissimmee. The guy next to me, chugging rum, was the smaller but rowdier of the two—he was rocking a Hedo Turkoglu jersey and waved his arms in the air when the Lakers shot free throws, going nuts if they missed, as though he’d caused them to brick it, while his bulky friend on the far side brooded and nursed a Heineken. “What’s wrong, Big Fella?” I asked.

“Aw, he don’t like sports,” said Turkoglu. “He just wants to smoke weed.”

“I’ve got weed,” I told him.

At halftime, we went up to Big Fella’s room on the twenty-second floor and I passed him a little baggie of homegrown to roll into doobies, while me and Turkoglu found the game on TV and raided the minifridge for airplane shots of Crown Royal and Jack. Soon we were all pretty fucked up. The game was a battle—Hedo and Kobe going toe-to-toe, and before long I was waving my arms along with Turkoglu when the Lakers shot free throws, and eventually we goaded Big Fella into waving his arms, too, as we all laughed and shouted.

During an ad break halfway through the fourth quarter with the score tied, I stumbled into the bathroom to take a leak, and somehow set my glass on the counter and knocked it off in the same motion, and it shattered to pieces at my feet. A second later, I slid backwards on my own puddle of ice and went crashing down—wham—to the floor. Something bit the side of my right hand, it felt like, and when I held my hand up, I saw darkred blood bubbling from a long wound that ran from my wrist to my pinky—I’d sliced myself good on a broken piece of glass. I winced, but had enough drink in me, it didn’t hurt too much, I just didn’t want to have to get stitches. Lying on the floor of Big Fella’s bathroom, I reached for a washcloth and wrapped it tightly around my cut-up hand, then began picking up all the broken bits of glass. Something caught my attention on the floor next to the little waste bucket under the sink—it was one of those long, glossy luggage tags stamped with your final destination that they slap on your bag at the airport before tossing it into the plane’s belly, which you tear off and toss out once you get where you’re going. But there was a name on this one, and it took me several dumbfounded seconds to process it cleanly—L. HACKNEY.

What the fucking fuck? I scrambled to my feet and charged out of the bathroom. Turkoglu turned his head from the game to look at me. “What the hell,” he said. “Holy shit, you’re all bloody, dude.”

I looked past him, at Big Fella, and held the luggage tag high above my head, shrieking wildly, “What the fuck is this shit?”

“Whoa, man,” said Turkoglu, rising to his feet. “I think you got overserved.”

“Is this true?” I howled, waving the tag, shaking drops of blood onto my neck and chin.

“Yeah,” said Big Fella. “I flew into JFK. So what.”

“For what?”

“What?” His eyes were glazed and red.

“You flew in for what? Why are you here?”

“For the Future Is Now conference, man.”

Three hours before, when I’d first walked into the Emerald Bell, the righteousness of my mission had sharpened my focus to a fine, deadly point, but now, caught off guard, drunk and stoned, I felt confused and frantic, like a man swarmed by bats. “I thought you said you sold cell phones!” I cried.

“Phil sells cell phones,” said Big Fella. “I run a literary agency. What’s it to you?”

“I don’t ‘sell cell phones,’” Turkoglu piped up. “I get retail stores to carry Nextel products. You make it sound like I’m hawking ’em out of my trunk.” He turned back to the TV and cranked up the volume.

I was losing it. “But I thought—I thought you guys worked together.”

I said nothing, struggling to fend off a strange rush of unexpected tears, and reached into my backpack with my un-bloody hand. One at a time, I drew out the Aquafina bottles of pee.

“Who?” said Turkoglu. “Me and him? Naw, I just met Lon downstairs, an hour before you showed up.” He leapt to his feet, cheering a blocked shot by Dwight Howard, and shouted at the TV, “Our house, baby! You’re in our motherfuckin’ house now!”

I stared at Big Fella—Lon Hackney—feeling sick with adrenaline, herb, sake, and bourbon. He looked like Jabba the Hutt dressed as a burned-out music producer for Halloween—long, scraggly hair, a wide, splotchy face, in a black turtleneck and black jeans. Not a salesman at all—what had I been thinking? He eyed me through hooded lids, warily, high as hell but aware that something dangerous had been set into motion. “Your name is Lon?” I asked him over the TV’s roar, with a bleat of hysterical laughter.

He nodded.

“Lon Hackney?”

“Yeah. Who are you?”

I said nothing, struggling to fend off a strange rush of unexpected tears, and reached into my backpack with my un-bloody hand. One at a time, I drew out the Aquafina bottles of pee. “Here, Lon,” I said. “Catch.” I lobbed them across the room to him, quickly, one-two, and he caught the first and fumbled the second; it bounced into his lap, gently fizzing.

Slowly, in his weed-dwindled, morally rotted, pea-sized Jabba brain, he began to put two and two together. His face went slack, and he slumped a little, took a deep breath, and said in a flat, low voice, edged with both fear and menace, “I know who you are. What do you want from me? Why are you here?”

The quiet, eye-of-the-hurricane drama of our long-awaited face-off was lost on Turkoglu—Phil, from Nextel—who couldn’t understand why we’d stopped paying attention to the game when the score was so close down the stretch. “Hey, you guys, shut up and focus! We need a bucket here!”

I felt like the German shepherd tied to a stake in the yard who for years barks ferociously at the little poodle next door, and then, when he finally breaks loose from his chain, races over, sniffs the poodle’s ass for a second, and then wanders off, directionless, down the road. All of life’s urgent pursuits are rendered meaningless once they’re actually in your grasp—I wondered why I’d thought confronting Lon Hackney would be any different. I still had to pee. I could pee on him, I mused. I could empty the bottles of pee over his head. I could shout at him and call him names. But what, in the end, was the fucking point? Here he was before me, a washed-up fat-ass, hiding from his own conference’s participants, lighting joints in a lonely hotel room, his two best friends a pair of dudes he’d just met that night, watching basketball with us though he didn’t even like sports. There was nothing I could say or do to knock him any lower. Still, I’d come to New York to make him stop, to end his writing contest scam. For my dad. For Ondrea.

“Lon, you fucker, you supreme fucker,” I said. “I know your fucking scam inside and out, so listen to me, you don’t have to deny anything, ’cause there’s no point in that. I know the scam exactly. Okay? I know. I know it all.” I kept my right hand raised high toward the ceiling, clutching the washcloth, and it’s possible that with all the blood dripping down my arm, I seemed crazier and more dangerous than I really was. “Here’s the thing,” I growled. “You got to quit. You got to quit this shit.”

Phil gave me a glance, thoroughly confused by what was happening, but too intent on the game’s closing minutes to worry too much about me and Lon’s detente. He was on his cell phone with a buddy in Florida who was also watching the game.

“I can’t quit,” said Lon, very, very quietly, almost inaudible over the cries of the announcers on the TV. “I need the money. I have a wife. I have a kid.” He rocked back and forth a little, inspecting the bottle of pee in his hand.

“You have real victims,” I said. “Go down to the Legacy Room. Talk to them.”

“It’s nothing they can’t afford,” he said, with a hint of bitterness.

“You know what the worst thing is? You don’t even read their books!” I reached into my backpack and pulled out the spiralbound novel that the woman from Minnesota had given me, Aiden’s Quest, along with the other books I’d collected. I felt my voice rising to a shout as I held them out and shook them in the air. “All these people, all they want is for their books to get read!”

“Guys, chill out!” snapped Phil. “Hit the peace pipe. Or take it into the hallway.” He said into his phone, “Yeah, no, just the usual riffraff that can’t handle their drink.”

Lon sat staring at the floor. His heavy girth weighted the bed down low, and I had the thought that it must be really difficult to go through life so obese. “I’m just trying to live my life,” he said. “What do people want from me.”

We fell into a stalemate. In the end, even if Lon shitted on some people’s heads, it wasn’t genocide. It was extremely fucking lame, is what it was, and truly hurtful to some, I was sure, having witnessed just the tiniest bit of his casual destruction firsthand, but he wasn’t prostituting 10-year-old girls, or abducting family pets, or selling guns to gangs—he was organizing failed literary conventions.

“Leave my room or I’m gonna call Security,” he said at last.

That pissed me off. “You know,” I said to him, “the only motherfucker who’s more of a loser than you is me. ’Cause I’m the one who’s gonna spend my life following you, hounding you, harassing you, dirtying your name, and mailing you bottles of pee, until I shut you down.”

“Aaiiieeeeeeee!” screamed Phil suddenly, from between us. He slid from the near bed, by the TV, where he’d been sitting, down to the floor, hands over his face. “You can’t leave that guy alone!” he wailed. “Fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck!” Derek Fisher had just drained a long three for the Lakers to send the game into overtime; they kept replaying the shot from different angles in slo-mo. “Fuck this,” he said, “I’m going downstairs to watch. You guys and your lovers’ spat, you’re bringing me down. It’s bad juju.” He grabbed a beer from the minibar and padded his way out the door, letting it slam behind him.

Somehow, with Phil gone, the room felt suddenly tense and unpredictable. Lon looked at me, upset, angry, and scared, as though I might rush him. “Well,” he said, wobbly voiced. “What happens now?”

“Here’s what happens, I think. I’ll tell you. Actually, one of two things.” I was making this up as I went along. “The second thing, what I don’t want, is—we fight. You’re a pretty big dude, and I don’t want to fight you, you’ll probably get some licks in, but I’ll warn you, I’m wily, I know how to inflict damage, and I fight like a cornered animal. But that’s no good for either of us. If you agree to the first thing, we don’t have to go to the second.”

“I can’t shut down the contests,” he said. “I wrote freelance for twelve years. I basically lived out of my car. I’m not going back to that.”

“Okay,” I said. “That’s not what I was asking. Here’s what I’m asking.” The room seemed to tilt on its side, and I wondered if my wooziness might be due to a loss of blood. “I’m asking you to drink that bottle of pee, right now,” I said. “Every drop.”

He lifted the bottle close to his face, as though mulling it over. “I don’t know,” he said at last. “Why do you want me to drink pee?”

“Everyone leaves your shitty conferences feeling burned. I want you to see what it feels like to get a bad taste in your mouth. A bad taste you’ll never forget.”

“Huh.” He slowly unscrewed the cap off the bottle and bent his head to take a whiff. Deeply revolted, he grimaced and screwed the cap back on. “I would throw up,” he said. “I can’t drink this whole thing.” He took a quick gander around the room, as though sizing up what objects close at hand—a lamp? an ashtray?—could be used as weapons, if things took that sort of turn.

“Drink half, then. Half is enough.” I scowled and took an imposing step closer.

“Oh God,” he said, burying his face in one of his meaty palms. He took a long, staggered breath, and shook his head back and forth. “Fuuuuuuck.” It seemed to me that somehow I’d gotten through to him, and that for the first time, whatever regret he must have had for his writing contest scams was finally beginning to surface. As he sat there, head bowed, I felt a burst of quiet satisfaction. But still, I intended to follow through with my improvised punishment. “Go on,” I said. “Bottoms up.”

Lon raised his head and stared at the pile of books I’d pulled from my backpack. “Look,” he said. “Here’s another idea. You want people to read those books so bad? Fine. I’ll read ’em.” Quietly, he went on. “I know I can run these conferences better. It’s just, I’m only one person.”

It rankled me that he was still ducking responsibility by making excuses, but he had a tone of genuine self-reflection that took me by surprise. “What are you saying?” I asked.

“I’m saying I can’t drink this bottle, but if you’ll give me a pass, I’ll make some changes. And I’ll start by reading those books.”

I thought about that for a moment, hesitant to let him off easy. But I wasn’t sure that drinking my pee was going to lead him to any greater epiphanies. “You’ll read every one of these books?”

“Yeah,” he said. “Every one. Hand ’em here.”

“What about all the other books people send you?” I thought of my dad’s essay collection, Brooklyn Boy, which had surely been tossed in a Dumpster as soon as his check had been cashed.

Lon nodded. “I’ll make sure they get read. That was the whole idea, from the beginning, to help people get their books out there. Mine, too.” He rubbed his ear.

“Fine,” I said at last. I picked up Aiden’s Quest. “You can start with this one. I met the woman who wrote it. She’s here. Downstairs. She entered it in your contest.”

“What did she win?”

“Third place, I think. Historical fiction.”

“Let me see.”

I limped over and passed him the pages. He turned it over in his hands, reading the back cover. “This sounds more like fantasy,” he said. “Historical fiction is more... historical.” He heaved a breath. “All right, I’ll read this one first.”

“Cover to cover.”

“Yeah. Cover to cover.” He gave me a look. “No more pee?” “No more pee.”

“You’re fuckin’ crazy,” he said, starting to laugh. “Fuckin’ nutjob. Okay, I guess we’ve got a deal. Shit.” He scooted up his bed toward the nightstand, where he’d mashed out a joint, sparked it, took a long hit, blew smoke toward the ceiling, and leaned back on a pile of pillows, fumbled a pair of glasses onto his face, and turned to page one. “Can you turn that TV down?” he said. “I can’t hear myself think.”

I reached for the remote and settled down on the other bed to watch the end of the basketball game.

“You better wash out that cut,” said Lon. “You think you need to get it stitched up?”

“I don’t think so.” But I got up and went to the bathroom to wash it out and wrap it in a fresh cloth. When I came back, Lon was making little interested reading sounds—a “Huh,” a “Hmmm,” and a chuckle.

I poured myself a nightcap in a plastic disposable cup—Canadian Club over ice—and sat on the edge of the bed, sipping it down, watching the rest of the overtime, while Lon, in his bed, slowly turned through the pages of Aiden’s Quest. With 30 seconds to play, Derek Fisher nailed another three to put the Lakers up, and they went on to win by seven, taking a threegames-to-one series lead, effectively crushing the Magic’s hopes of a championship. I thought of Phil, down in the bar, or maybe back in his own room, glumly removing his Turkoglu jersey, and starting to drunkenly prepare for his presentation the next day at Nextel HQ. Sometimes in life things didn’t go the way you hoped and imagined they would, I thought, resting my head back, but still, somehow, it all worked out okay.

I woke up hours later. It was maybe three or four in the morning. The room was dark and quiet, apart from flashes from the TV and the hushed voices of golf announcers. My head was pounding, my hand burned where I’d sliced it, and my ankle ebbed with a low-grade but steady ache. In his bed, turned away, webbed in sheets, hair flopped this way and that, Lon breathed heavily, a half-snore.

I stood up and inspected my hand. The wound had closed and was matted with dried blood, which looked black in the TV’s dark flicker. I headed for the door. Just as I reached for the handle and turned it, a sound startled me from the far side of the room.

“Hey,” Lon whispered in the darkness. “Hey, is that you? Guess what?”

“What?” For some reason, I was whispering, too.

“I finished that book.”

“You did?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s good,” I said. “That’s really good.”

“Yeah. Yeah, guess what?”

“What?”

“I’ll tell you something,” Lon said. “I got to tell you. It was pretty good.”