Outside

Outsider artists draw outsider patrons, some who smell like horses. Not even the art gallery world’s aura of intimidation will keep them away.

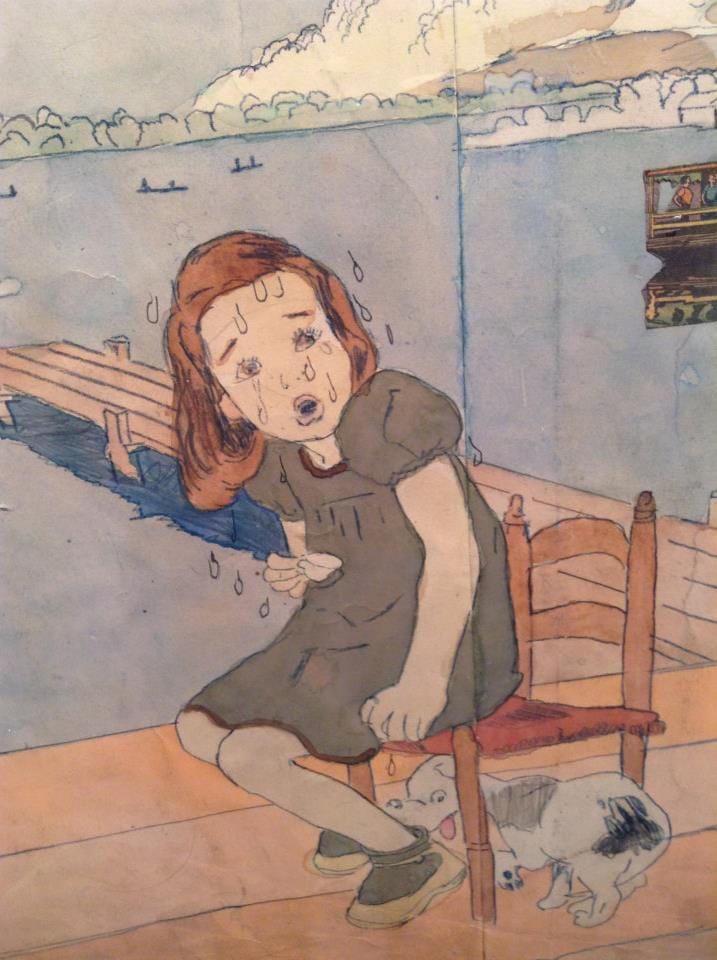

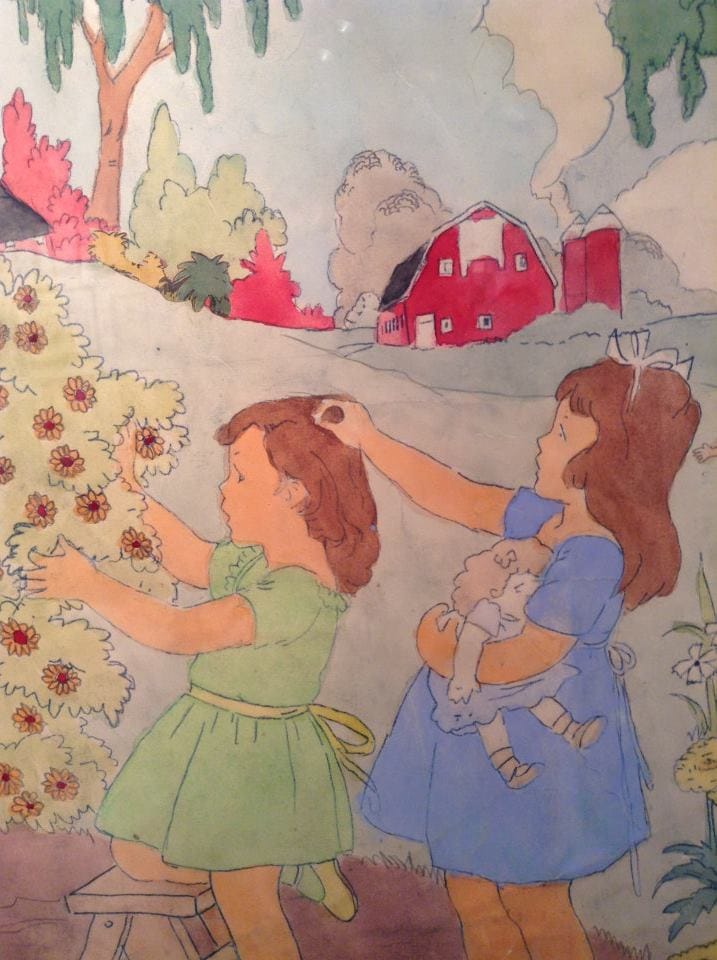

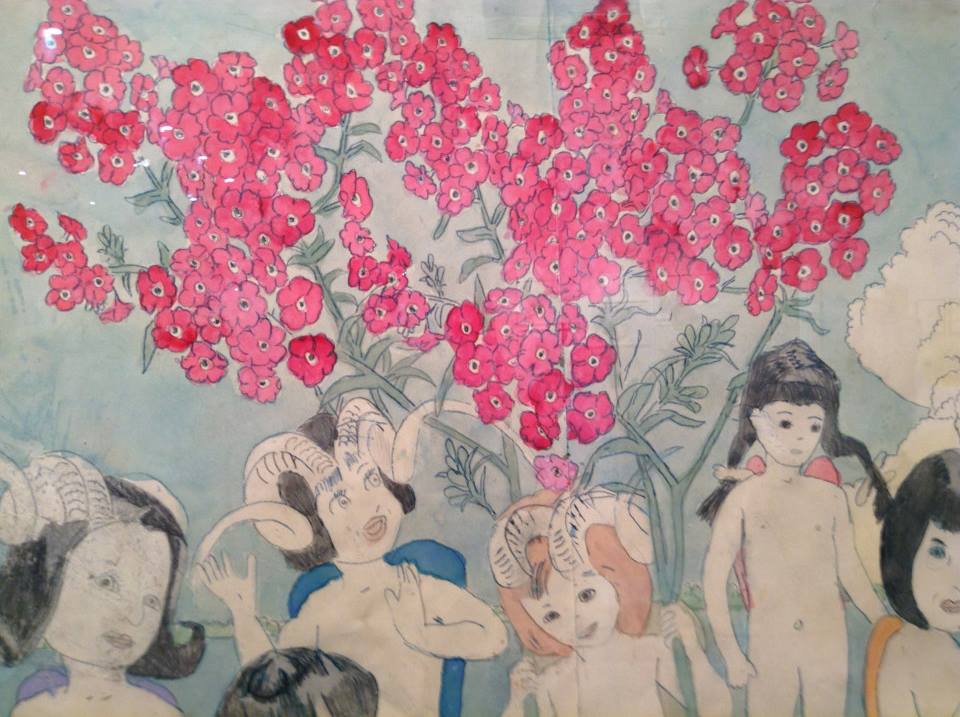

I know I smell like horses. I’ve come straight to the Outsider Art Fair in Chelsea from teaching riding, and I’m still wearing tall boots, jeans, and a T-shirt. I’m alone and looking at art. I take photos of the ones I like the most: William L. Hawkins, Susan Brown, Henry Finster, and a beautiful sixty-something woman with pink hair and colorful clothes who is her own work of art. And, of course, the Henry Darger scrolls. I get up close to them to photograph the details: a strange creature that could be a cat, the bright pink of a magnolia tree, a little girl sobbing.

The gallerist at the Andrew Edlin Gallery is kind to me. He tells me they rotate their Darger scroll once an hour, and that I should come back to see it again later. I ask how much and he tells me one million. Maybe he can tell I don’t have one million. But even if he can, he is kind.

I walk over to a different gallery to see another Darger scroll. I practice taking a panorama, walking slowly to the side and keeping the camera steady. The event program encourages online sharing, and lists a hashtag for the event. I sit down for a moment in one of several empty chairs and write out something on my iPod Touch to post on Twitter. I want to say how amazing the Darger scrolls are, and how everyone who can should come see them.

The gallerist interrupts me. “Can I help you?”

“No, thank you.” I continue to write.

He clears his throat, and his face contorts. “I paid for this real estate,” he says. “So you can take your—texting—elsewhere.”

I look up. I don’t know what to say. I look down at my boots. I feel a wash of shame. I don’t belong here, in Art World. I don’t have the money to buy a painting. I’m messy and running from work.

I am an outsider at the Outsider Art Fair.

I don’t say anything. I get up and walk away. I look at some other paintings. I don’t tell anyone to go look at the ones I liked. I keep them to myself. I think, Maybe he only wanted someone sitting in that chair if they were writing out a big check for a painting. I force myself to consider compassion. Maybe the gallery is struggling. Maybe they really need that big check.

Then I consider pranking him. How does he know that I wasn’t texting my billionaire boyfriend or wife, my boss or my assistant? “I like this one, but do you think it might look strange next to our Renoir collection?” I could talk loudly on my cell phone and say, “I was going to buy this one, but the gallerist was rude.” Could he tell I didn’t belong?

Henry Darger was locked up in the Illinois Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children because of “self-abuse,” the preferred early-1900s euphemism for masturbation. He worked as a janitor, and it wasn’t until he died that his landlord discovered yards upon yards of scrolls in his apartment, including often-disturbing artwork and a 15,000-page novel. The images form a fractured fairy tale, familiar and yet completely their own thing. The cheerful colors manage a melancholy. When the children smile, it’s only because they don’t know what horrors may come next.

I go back to visit the first scroll, with the kind gallerist. He shows me a small Darger that’s not displayed. I ask if I can photograph it. It’s the closest I’ll get to owning one, and that’s OK.

“Do you ride?” he asks.

“I do,” I say, curious before I remember my boots.

“I do, too,” he says.

I wonder how Darger felt, living as an artist in secret. His remarkable talent was hidden from the people who saw him every day, who looked over at him and made their own assumptions. Meanwhile, his head held gorgeous, gruesome masterpieces.

I want to remember this with everyone I meet.