Press Rewind

What one journalist learned by vicariously sitting in on David Carr’s master class—with only his teacher’s reputation, extant syllabus, and students’ recollections to guide the way.

A few weeks before New York Times media critic David Carr taught his first class at Boston University, the syllabus for his “Press Play” course appeared online. Press Play, Carr wrote, “aspires to be a place where you make things. Good things. Smart things. Cool things. And then share those things with other people.” Carr’s syllabus revealed for his readers the high hopes of an exacting and acerbic critic, a journalist that Times editor Dean Baquet called “the finest media reporter of his generation.” His online fan club—which included nearly half a million Twitter followers—shared the syllabus with each other, parsed his reading list and excerpted the candid “personal standards” Carr set for his students. (“If you text or email in class, I will ignore you as you ignore me. It won’t go well.”) Plenty of working journalists seemed ready to quit their jobs and go back to school.

On Feb. 12, Carr crumpled to the floor of the Times newsroom. He was pronounced dead that evening; an autopsy identified lung cancer and heart disease as contributing to the death of the 58-year-old journalist. Carr died in the middle of his second semester. The Times published his Press Play syllabus as his final column and praised Carr as a “natural teacher.” Ta-Nehisi Coates, who worked for Carr at the Washington City Paper and took over Carr’s second Boston class, told me he knew Carr “as a teacher before I knew him as a boss.”

After Carr’s death, his colleagues at Boston University convened a few people to review the syllabus for his spring course, on media criticism, and determine how best to continue the class in his absence. Those people included Coates and Clinton Nguyen, one of Carr’s Press Play students who later became his teaching assistant. “We spent a lot of time trying to recreate his thinking on why he picked the pieces he did,” Nguyen told me during an interview.

Press Play was Carr’s only complete class, but the syllabus and course materials reflect his unusual intellect. Carr read against his preferences and interrogated his own assumptions. He respected the power of narrative, prized creativity, and disdained grandstanders and bullshitters. He fixated on certain mediums and personalities and doubtless ignored many others. He liked what he liked, but he never knew what he might like next. If his celebrity-journalist status made “Press Play” attractive, then his thinking—contrary, scattered, scrupulous—made it exceptional. To recreate Carr’s thinking, as Nguyen and Coates and others tried, is to deny his death and keep learning from him.

This summer, I took a compressed version of Carr’s class. I worked through the reading assignments on his syllabus, week by week. I spoke with students from Press Play, and read his feedback on their work. I didn’t do the writing assignments, but I wrote my own final of sorts—a companion piece to his syllabus that followed his lessons.

“Before we begin the semester…”

In 2012, I moved to New York to work at the Columbia Journalism Review. My job was to contact journalists like Carr to share my own magazine’s shrewd takes on reporting, ethics, and the business of news, to encourage and support their work. (I used the compound modifier “clear-eyed” in more than one official report; I was watching a lot of Friday Night Lights.) On a few occasions, I emailed Carr to promote my colleagues’ work, with the hope he’d do the same. (You can imagine the cockiness.) His lack of a response confirmed what I felt was true: There was little I could teach David Carr about journalism.

In New York, I felt mastery over very little outside the apartment I shared with my wife. I wanted Carr’s authority—the strength of his convictions, the confidence that his voice rose above the din of the city—and so I read his “Media Equation” column every Monday morning like I had homework to do. When I left New York, it was partly because I wanted to write a book like The Night of the Gun, Carr’s memoir about his crack addiction, recovery, and struggle to report the blurry borderland between memory and reality. I applied to graduate school in Minneapolis—where Carr was born and worked at the now-shuttered Twin Cities Reader. When I was accepted, I wrote an email to Carr, where I tried to endear myself to him (“You like the Replacements? Why, I like the Replacements!”), then thought better of sending it. I moved to Montana, but still studied “The Media Equation” each week. When I started teaching, I still appealed to Carr’s authority on some matters, and made my students read his writing. I thought of him as better than human, which of course he wasn’t. I expect that many of his students thought the same.

For their first Press Play class, Carr’s students read three pieces of journalism by three different writers, including “The Wrestler,” Carr’s post-mortem tribute to Philip Seymour Hoffman. “Covering entertainment,” Carr writes early in the piece, “means that you come across people whose faces you first saw 20 feet tall on a movie screen. They tend to shrink when you meet them.”

Carr loomed large, in the movie-screen sense. There’s a scene in Page One, Andrew Rossi’s documentary about the New York Times, in which Carr interviews a few Vice staff members about their company’s media partnership with CNN. “What the fuck,” Carr begins, “is going on that you’re doing business with CNN?”

Shane Smith, a Vice co-founder, slumps in his seat as though Carr has called him into his office. He tells Carr about a reporting trip to Liberia, and Rossi cuts to footage of Smith talking with a Liberian warlord about cannibalism. “The New York Times, meanwhile, is writing about surfing,” Smith tells Carr, who stops the interview for a brief lesson.

“Before you ever went there, we had reporters there, reporting on genocide after genocide,” says Carr. “Just ’cause you put on a fucking safari helmet and went and looked at some poop doesn’t give you the right to insult what we do.”

“I’m just saying that I’m not a journalist—”

“Obviously,” interrupts Carr. “Continue.”

None of the students I spoke with had seen Page One before that semester, but they feared him. They were intimidated by his intellect and his tenacity as a reporter. A few of them read “The Media Equation” with some frequency. Several had read The Night of the Gun.

“I didn’t have many expectations other than he was this big scary hero of mine who existed and wrote amazing things and was terrifying,” said Emily Overholt, who read Carr’s memoir before college.

Brooke Jackson-Glidden, another student, said, “I felt completely nervous. I was wearing a blazer. I didn’t know what I was doing.”

Why do we fear those who we also admire? Overholt found the simple fact of Carr’s existence “terrifying,” and it seems like some of her classmates shared that terror. I don’t think everyone experiences this sort of intellectual insecurity, but I do think we often revere those people who embody our most noble ambitions, our best hopes for ourselves. Such people—let’s call them teachers—seem to know the world the way we want to. And so we desperately hope they might recognize our potential, forgive us our shortcomings, and teach us.

When I asked Nguyen what he knew about Carr before the class, he replied, “I knew that he was a big name at the New York Times, and I knew that he had a big mouth. And that was something he admitted.”

And then they met him. Carr had a cigarette before the first class started, and borrowed a lighter from one of his students. Then he walked into the class—“shambled,” another student put it, and that sounds right. Rumpled blazer, T-shirt, red iPad. A greying Alfred E. Neuman, his head swinging, pendulous, on top of his thin neck. He’d open his big mouth, and the room was his for three hours.

“That’s pretty much how the class went,” said Nguyen.

Week One: “State of Play”

For the first few weeks, classes followed a loose template. First, Carr introduced a guest speaker. Then he took a cigarette break. Then he led a discussion about the week’s readings. For “State of Play,” he’d assigned pieces by Clay Shirky and Alexis Madrigal about the nature of storytelling experiments. Madrigal, a former staff writer for the Atlantic and current editor of Fusion, wrote an obituary for “the stream,” the term for how content providers like Twitter and Facebook deliver information: an unending cascade that, Madrigal argued, had come to its end.

“I think people will want structure and endings again, eventually,” Madrigal wrote. “Edges and balance are valuable.” In part—and let’s not strike the existential chord too hard—because edges and balance give value.

Carr picked the first week’s readings to give his students an “overview of the state of narrative and content.” To me, it seems like Carr also wanted to equip students with the language necessary to critique narrative and content, the tools necessary to map their limits.

Madrigal’s essay is, essentially, a vocabulary lesson. Madrigal defines “the stream” and offers examples like “Snow Fall,” a Times digital project that interspersed narrative writing with GIFs, large digital images and original video to create a novel multimedia story about an avalanche. (Just as “stream” became a noun to describe content delivery, “snowfall” became a verb to describe…well, doing what the Times did. A lot of places tried similar storytelling projects, including my old alt-weekly.) Carr paired Madrigal’s essay with “Baptism by Fire,” a “snowfall”-styled piece that profiles a rookie firefighter and follows him through his first blaze. I’m not sure what Carr’s students thought about the writing, which I found a bit breathless. But the multimedia content—interviews with firefighters and three-dimensional renderings of the burning building—provided the prose with a necessary and lively counterpoint, a translation, like shadows thrown by flames.

Carr also assigned an essay by Clay Shirky, who writes frequently about the internet’s evolving relationship with the way news is created and distributed. In his essay—written in 2009, before “the stream” and Instagram and the iPad—Shirky likened the way online content sharing upset the news business to the cultural and economic tumult that followed the invention of the printing press. “Experiments,” Shirky argued, “are only revealed in retrospect to be turning points.”

Things were quiet, which was reminder enough that I didn’t have classmates, or guest speakers, or the rasp of Carr’s voice in my ear.

I bet Shirky’s essay sounds different at the end of a semester than it does at the beginning, but it makes for an auspicious starting place. Carr charted experiments in reporting, storytelling, and the news business every week, and often circled back to declare turning points and dead ends. In Press Play, Carr encouraged the spirit of experimentation he admired in others; the course, as he envisioned it, was a space for students to tinker with the fundamental units of narrative, a storytelling lab.

“Things will be exciting,” Carr wrote to his students, “and sometimes very confusing.”

Carr also seemed to caution his students against reckless experimentation. Alongside Shirky’s essay, Carr’s students also read a piece of media criticism by Jessica Testa for BuzzFeed. The title—“Why did Jodon Romero Kill Himself on Live Television?”—suggests a psychological investigation. But Testa’s essay is actually an indictment of a medium: the live, televised coverage of car chases. When news teams cover events like car chases as they occur, those teams sign on for unpredictable and potentially traumatic consequences—in this instance, broadcasting the moment Jodon Romero emerged from a stolen car and shot himself in the head. Whether Carr intended Testa’s piece to work alongside Shirky’s, one conclusion seems clear enough: Even when some experiments become turning points, their products can be unwieldy.

I read the materials for “State of Play,” and each of Carr’s subsequent assignments, on my laptop, at a large wood table in a country house with spotty internet. It was gravel roads for miles around, so on the rare occasion that a car passed the house, I could hear it coming a ways off. But usually things were quiet, which was reminder enough that I didn’t have classmates, or guest speakers, or the rasp of Carr’s voice in my ear.

Week Two: “Choosing Targets”

Emily Overholt told me that readings “kind of fell by the wayside,” but I hadn’t realized how quickly until I asked about David Foster Wallace and “Consider the Lobster.”

“We didn’t read it.”

Overholt explained that the readings were icebreakers at first. Then they were simply part of Carr’s lesson plan: He wanted students to read different approaches to storytelling, hear different voices, develop different approaches to their craft. But as the semester picked up steam and students began their own reporting and writing assignments? “It definitely became clear that the readings were not as much a part of the class,” she told me. Skipping “Consider the Lobster” was “a gift,” she recalled Carr saying, “because it is massive.”

I felt let down. Sure, strict adherence to a syllabus makes a teacher inflexible. And there were two other sterling “readings” that week, anyway. For his profile of Harvey Weinstein, Carr bobs in the wake of the contentious Miramax co-founder, close enough to see how Weinstein makes waves. Carr’s story also features some elegant descriptive work. (Weinstein’s neck, for instance, is “inferred, not seen.”) Sarah Koenig’s “Dr. Gilmer and Mr. Hyde” was even better: an hour-long radio story about a physician who examines the case of another doctor and convicted murder who worked at the same office and shares his name. Koenig’s story showcased the same meticulous reporting and just-thinking-out-loud-here narration she brought to Serial, and in a single episode rather than a dozen. (The ending is tidier, too. Though I ask you, Serial haters: Why should all stories be tidy?)

I also felt a bit surprised by Carr’s hubris. The semester had just begun, and yet he had already assigned two of his own pieces. The previous class had felt empty without Carr’s voice; now, I wondered whether I was being exposed to too much of it, and at the expense of others.

Which makes this as good (and as bad) a place as any to mention that more than one person offered to me that they had some concerns about David Carr. Here’s an example: During the summer, a friend from Virginia came to Montana to visit. When I explained my project to her, she asked me whether I thought Carr was a misogynist, whether he favored male writers over female writers. I had never really considered the matter; most of the students in Press Play were women, and this piece in the Washington City Paper included tributes from journalists like Garance Franke-Ruta, Natalie Hopkinson, and Stephanie Mencimer, all women who Carr hired.

Anyhow. Carr had cut a piece by a white male writer with more name recognition than most of the journalists he’d included on his reading list. And the pieces he kept were fine. They were good, even.

Still: Carr cut “Consider the Lobster”?

When I began this project, I was finishing grad school. One of my final classes was a David Foster Wallace seminar. I’d re-read most of his nonfiction and finally finished Infinite Jest. So had Carr. Kind of.

“I am the kind of person that read Infinite Jest without reading the notes and loved every second of it,” Carr told an interviewer in September. (“Without reading the notes”? I’m not sure that should count.) Wallace was the writer Carr said he’d most like to meet. He’s on my list, too, and I had wanted to hear one of my favorite reporters talk about one of my favorite thinkers, even if it was secondhand. Now I wouldn’t get to.

So, since Carr deviated from his own script, why shouldn’t I do the same and steer us back for a moment?

“Consider the Lobster,” published by Gourmet in 2004, begins as a travelogue about Wallace’s trip to the Maine Lobster Fest. Then it turns a corner. Wallace wanted to write about suffering, and about the implicit ethical choices a person makes when he decides to “boil a sentient creature alive just for our gustatory pleasure.”

“Isn’t being extra aware and attentive and thoughtful about one’s food and its overall context part of what distinguishes a real gourmet?” asked Wallace. The implication: Isn’t this just the sort of morsel Gourmet subscribers love to nibble on?

“What were you thinking when you published that lobster story?” one reader replied in the next issue. “Do you think I read your magazine so you can make me feel uncomfortable about the food I eat?”

Carr assigned “Consider the Lobster,” alongside his Weinstein profile and Koenig’s radio story, so his students could get a sense for how some subjects “lead to remarkable stories.” And, yes, trailing Harvey Weinstein (once he lets you) and meeting a source like Koenig’s early might mean they pull you toward some deeper, more complicated story.

But I’m not so sure the lobster led Wallace to a remarkable story. So many of Wallace’s essays—about cruise ships, conservative talk radio, the political slants of dictionaries—are the products of a writer who worked, hard, to better understand the culture we’re all submerged in. Likewise, it would be a mistake to say that Weinstein led Carr anywhere; rather, Carr worked his way close enough to hear “The Emperor Miramaximus” examine himself in his own words. (Weinstein might have begrudged Carr the access; actor Tom Arnold claimed Weinstein once told him, “Your fucking friend David Carr is an asshole.”) In that way, Wallace is no different than Carr. One man’s lobster is another man’s media mogul. Either way, you don’t catch a thing if you don’t do a bit of fishing.

Week Three: “You Are What You Type On”

Carr structured Press Play around Medium, which had made an early reputation for itself as a new forum for adventurous (and—shudder—“longform”) nonfiction—a reputation Medium has distanced itself from more recently.

For Week Three, Carr assigned “The Remains of the Night,” a personal essay published on Medium, about picking up garbage in a secluded portion of Prospect Park. Elizabeth Royte paces her story with pictures of her findings: lubricant, condoms, improvised sex toys. “For me, garbage is more of a medium,” she writes, “a portal into other people’s lives.” Royte’s shots are well composed and carefully integrated into the story, and she includes a few relevant infographics. As a result, the portal leads to more intimate places: the author’s anger toward the littering, but also her tenderness toward those people whose sexual flotsam allow her a glimpse at their lives.

Medium was also the launch pad for Epic Magazine, an online publication that’s big on narrative thrills. Carr assigned a few stories from Epic, which was founded by Wired contributing editor Joshua Davis and Joshuah Bearman, whose feature for the same magazine served as the basis for Argo. In a column he called “Magazine Writing on the Web, for Film,” Carr wrote that Bearman and Davis had sold the film rights to a combined 18 stories. When Bearman showed Carr an early draft of an Epic story, Carr wrote, “The visual narrative is gorgeous, with big photos and artfully arranged text that would look good on almost any device.”

I’d wager there were a few things going on in Carr’s head. First, there’s that quote—“any device”—and the hope that a deeply reported magazine piece functions well no matter your screen size. (Though, for “Deep Sea Cowboys,” a story by Davis for Epic and part of this week’s homework, I used an HDMI cable to read the story on my TV, and the visual narrative was gorgeous.) There’s also a concern for multimedia storytelling: If journalists create audio and video documents in the course of reporting a story, then how might those documents do some of the work of the prose? When a 55,000-ton ship starts to capsize, can photos convey the magnitude of the scene in a way that text can’t?

Moreover, what do Carr’s assignments say about the responsibilities of journalists and the preferences of their readers? Some reporters may be expert multimedia content producers, but I’d imagine that most dig for facts better than they wield a camera or edit sound, or vice versa. A news team could conceivably do it all well; if that’s the case, then when does multimedia storytelling become a spectacle that distracts from reporting? When should the voice of the reporter be made subordinate to other media?

Maybe I’m projecting. I’ve gone to report on stories with my backpack stuffed with video cameras and microphones, and placed lenses and viewfinders in front of my eyes to “better” document events as they happened. In 2010, while covering the murder of a University of Virginia student by her ex-boyfriend, I attended a candlelight vigil and filmed a three-minute a-capella performance of a Pink Floyd song. Was that time well spent? Probably not. Did the video further my reporting or improve how I delivered it? I can’t see how.

But that’s the benefit of experiments. Carr’s students weren’t writing conclusions—at least, not yet. They were testing hypotheses, learning how to synthesize their stories from their constituent parts. And Carr wanted his students to work in a medium that enabled risk-taking.

“Much of it will be text,” he told students about their own work for his class. “But if you want to make magic with a camera, your phone, or with a digital recorder, knock yourself out.”

Week Four: “Collaboration”

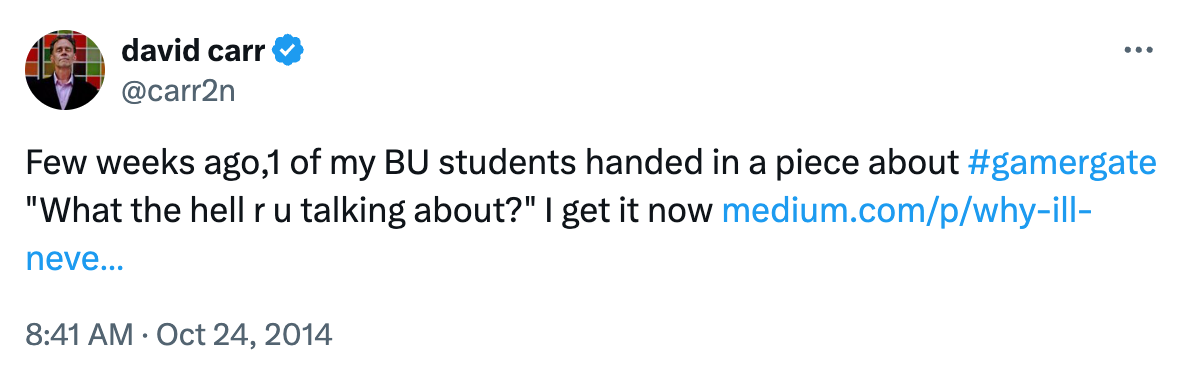

One of Brooke Jackson-Glidden’s early pieces for Carr was a personal essay about Gamergate, about issues of misogyny in online video-game communities. (If you didn’t follow, then here’s a Gawker explainer that touches on a few particulars.) She told me it was merely “something about Gamergate.”

“The point is, I was writing a lot of social justice-y stuff I couldn’t totally understand,” she said. Carr’s first comment on her story? “This is kind of a mess.”

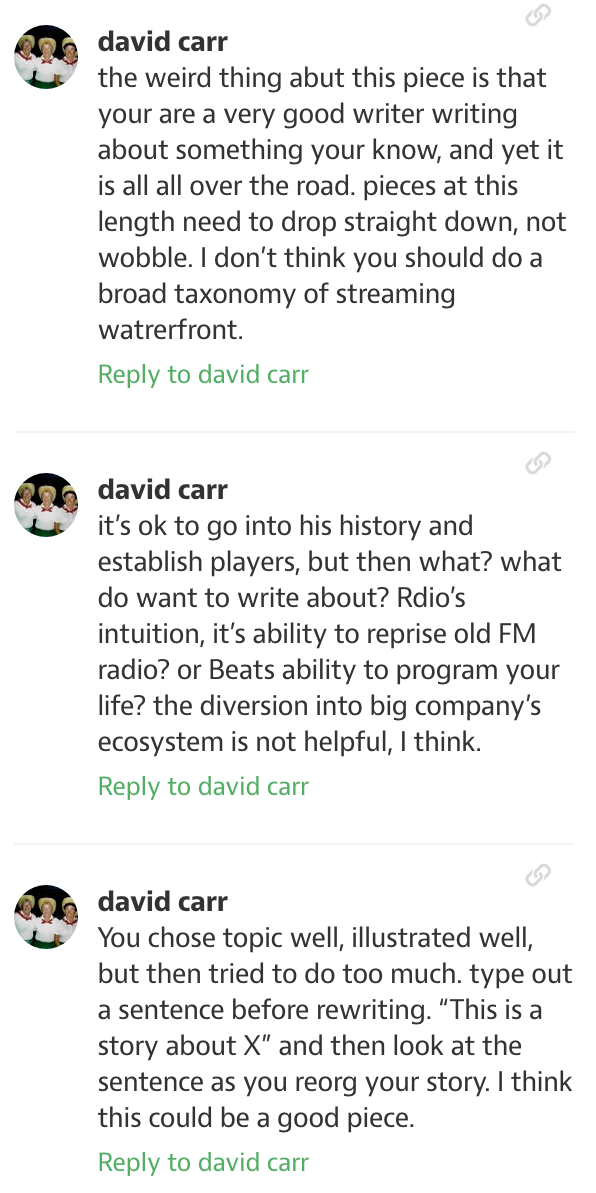

Carr was blunt. When Nguyen wrote about competitive strategies among free music streaming services for his first assignment, Carr cautioned him against writing that was, at moments, “kinda headsnapping,” “all over the road,” and “termpaperese.” Carr, said Nguyen, “was keen on pointing out when people were being lazy.”

And, while students were free to ignore Carr’s feedback, they did so at their own peril. “He told us if there was something he said that we really didn’t agree with, we could choose to keep it,” said Overholt. “But we’d know he really didn’t like it.”

After her first draft, Jackson-Glidden went to Carr’s office. He offered her a handful of jellybeans from the stash he kept on his desk, and they talked about her story, which was bulky with jargon. Instead of writing about a subculture, Carr said, she’d written for one. What is your experience of this, he asked her. Why does it matter to you? Jackson-Glidden pledged to get him a better story in a week.

“I think I spent a lot of that class trying to redeem myself,” said Jackson-Glidden. “I think that was something he was familiar with.”

The same week Carr workshopped his students’ work, he asked them to read two more stories he’d worked on. The first, “My So-Called Stalker,” is an anonymous account of one woman’s four-year interaction with the violently delusional man who tracked her, and with the law enforcement system whose seeming indifference jeopardized her safety. Carr published the story when he was editor of the Washington City Paper, and once called it “the story I cared most about.” The second, reported and written by Carr, is a deeply reported story about the Tribune Company, whose acquisition in 2008 by Sam Zell coincided with complaints of a culture of sexual harassment perpetrated by executives. Carr’s reporting on the Tribune Company became the dramatic peak of Page One.

“It’s gonna be a pretty rugged story, and I want it to be fair, which is why I’m calling you,” Carr tells a company spokesperson in a scene from the film.

The stories are interesting choices for a week when Carr’s students were focused on collaboration. “My So-Called Stalker” preceded national debates about the protective rights afforded to victims of domestic abuse and stalking, but it also came before stories like Sabrina Erdely’s discredited Rolling Stone feature on campus rape. The City Paper’s decisions—to print a one-sided account, by an anonymous author—suggest what must’ve been a great deal of trust between writer, editor, and publisher.

If “My So-Called Stalker” was the story Carr was most proud of, then his Tribune Company exposé was a fan favorite. I doubt Carr would have billed it as such. Clinton Nguyen told me that Carr didn’t introduce his own work with much fanfare. Some pieces, like his Weinstein profile, “he didn’t touch on very much,” said Nguyen, who added that Carr also introduced his essay about Philip Seymour Hoffman as “a good example of off-the-hours writing.” For “Me and My Girls,” an excerpt from his memoir about his addiction, grad student Prim Chuwiruch said Carr “explained that everyone has demons, and sometimes those demons are good for our work because they give us an interesting edge. The key is to embrace them.”

For a week devoted to “collaboration,” Carr’s story on the Tribune Company is a neat fit. For the story, Carr spoke with more than 20 current and former employees to substantiate claims of an abusive culture, and assembled the story with input from his editors and researchers. Stakes were high: A Tribune Company spokesperson called Carr’s story a “hatchet job” on the phone, and that was prior to publication. If Carr felt confident about his work, then surely some of his confidence came from sources and colleagues whose efforts helped his story succeed.

In Carr’s office, between jellybeans, Jackson-Glidden confessed to Carr that her Gamergate story confirmed a doubt she had in herself. “I worry I might be a case of wasted potential,” she told him.

“It’s probably true until it isn’t,” he told her. “Even when it is no longer true, you probably won’t know.”

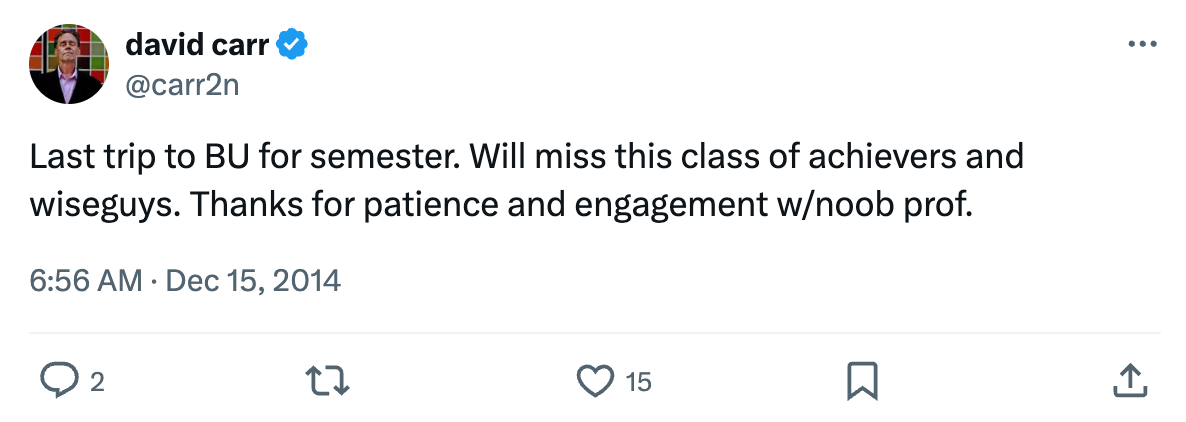

Jackson-Glidden rewrote the story and published a new draft on Medium. Then Carr tweeted:

Several of Carr’s students told me they felt unhappy with how their assignments turned out. “It wasn’t the story I wanted it to be,” one student told me about her final. “It wasn’t the story David wanted it to be either.”

If you’ve worked as a journalist, then this isn’t news to you. Doing the work means learning to live with dissatisfaction. Most editors don’t have time to stroke your ego after it’s been bruised. Sources will assume they know your angle and tell you to fuck off. Your mistakes will feel unforgivable; your corrections will be preserved for all eternity. But, as David told one student, “We like to make our mistakes in public.”

Week Five: “New Business Models for Storytelling”

Homework? “Just the readings.” Of the three assigned pieces, the most interesting was an overview of content marketing by Shane Snow, Chief Creative Officer of the branded content company Contently.

Branded content is a term for companies that publish “high-quality stories told on behalf of commercial clients,” Carr wrote in a column, though he qualified that description: “Over the years, this content has had an unsavory reputation—most have been infomercials masquerading as editorial content.” It’s an interesting nexus, then, between journalism, business, advertising, and ethics. Carr wrote that General Electric once employed Kurt Vonnegut as a corporate storyteller. Now GE works with media companies that help supply a corporate-owned newsroom with content that GE hopes will appeal to customers, written by (mostly, I imagine) well-meaning bloggers whose publishing affiliation with GE suggests corporate support for “thoughtful” analysis and discussion. A quick search on GE’s IdeasLaboratory.com (“where influencers convene”!) turns up pieces like “The Robot Soul” and “The Rise of Democratization” and “Women Don’t Need Quotas, They Need Opportunity,” written by the Tupperware Brands CEO, who uses the tactless line, “Invest with a woman and you’ll get higher returns.”

Snow’s company pairs writers with corporate brands that want to use storytelling to improve business. “Storytelling is the best way to build relationships with audiences and make them care about your brand,” the site says. “And Contently is how the most effective brands do it.”

Which is interesting because Contently’s roster of freelance contributors includes plenty of journalists. Snow published Contently’s ethical standards for both branded content and journalism. But those ethics were published in a “magazine” on the Contently site. Should that magazine be considered advertising for Contently? If so, is Contently touting its ethical credibility in order to sell its services?

Snow also discloses Contently’s marketing business, but disclosure doesn’t necessarily equal transparency. Here’s an example: A post on Contently that rounds up “the best branded content in June” claims that YouTube “helped normalize homosexuality and provided a comfortable platform for gay people to talk about their lives” because it hosted videos created by and featuring gay men and women. The post is clearly about branded content, but it attributes YouTube’s #ProudToLove montage to pure altruism without reminding readers that any popular footage on YouTube serves YouTube’s business interests, too.

Imagine Scheherezade before the king. Her life as a storyteller—her life, period—required constant innovation. One thousand unique stories. Repetition meant death.

(Also: David Foster Wallace was deeply concerned about this sort of thing, and I’m certain he would’ve been pissed to see A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again on the Contently homepage this summer, above logos for NBC Universal and TD Ameritrade, especially when said book’s title essay includes this argument: “Whatever attempts an advertisement makes to interest and appeal to its readers are not, finally, for the reader’s benefit.” But let’s not get distracted again.)

Snow’s article on branded content was published on Poynter, a leading media watchdog. He mentions and links to Contently numerous times, and uses a client of Contently’s branded marketing arm as a source. Does that make Snow’s article an advertisement for Contently and its clients? Does it make Snow a journalist? The rise of branded content (and its cousin, native advertising, which Carr called “advertising wearing the uniform of journalism”) suggests, among other things, that many people are easily taken in by storytelling. Narrative becomes a way to commodify your attention. Contently’s transparency may be admirable, but should we admire the work that it does?

I’m being stubborn and pissy here, so how about a few overly simple reminders? Journalism has a long relationship with advertising, and the news business has suffered from declining ad revenues, plus people are free to support the businesses they choose. To his credit, Snow seems interested in clarifying the relationship between journalism and the money that frequently supports it, perhaps even educating those people who consume news the way others consume advertising.

Maybe it’s enough that Carr assigned the piece as a reminder to his students that the relationship between advertising and journalism deserves steady vigilance. If Contently’s business model succeeds, Carr wrote, “it would be a good story to tell.” But if it doesn’t, or shouldn’t, then the story should still be told—if not by Carr, then perhaps by one of his students.

Week Six: “Storytelling Innovations”

This week, Carr’s students watched a short documentary about the relationship between India’s lack of toilets and incidents of sexual assault. They read “Zombie Underworld,” Mischa Berlinski’s tale for Men’s Journal about his efforts to navigate Haitian secret societies and return a “zombified” woman to her family. (Carr’s students read Epic’s “remastered” version of Berlinski’s story.) They watched the music video for Arcade Fire’s “Reflektor,” an interactive narrative where viewers can alter the video’s effects on their laptop with the wave of a phone. And—perhaps most surprising, given its companions—they read Caity Weaver’s Gawker story about a Delta Gamma sorority sister whose idea of motivational speech was so violent and profane that Funny or Die hired Boardwalk Empire actor Michael Shannon to read it aloud (NSFW audio).

How did Carr imagine these pieces fitting together? I asked Prim Chuwiruch how Carr had explained the readings to the class.

“The best way to go about the course is to go in with a blank slate,” she told me. “Get rid of your biases, whatever styles you like or voices you enjoy, and read those pieces as a blank reader. Take knowledge from what it is.”

Imagine Scheherezade before the king. Her life as a storyteller—her life, period—required constant innovation. One thousand unique stories. Repetition meant death.

Carr spent 13 years at the New York Times, and wrote roughly 2,000 stories and columns for the paper of record, a paper he loved. That’s in addition to his years steering the Washington City Paper, his work for New York and Atlantic Monthly, his memoir. Sure, Carr asked students to read a lot of his own work, but the range of those pieces—profiles and personal essays, writing that showcased deep investigative reporting and rhetorical versatility—was unique. Plenty of writers can file 2,000 stories in a lifetime, but few use their writing to reveal themselves to us as fully as David Carr often did.

Week Seven: “The Holy Music of the Self”

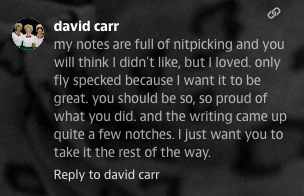

For their second assignment, Carr’s students wrote profiles—of musicians, immigrants, calligraphers, radio hosts, bookstore owners, burger artists, and someone called Super Giraffe. Carr read each and posted his notes in the margins (“clunky” and “passive writing” and “memorable and unlikely” and “me likey”) and then shared a few final drafts with his followers.

Students had the option of making private the comments and edits from their classmates and Carr. Clinton Nguyen “kept edits out and left trenchant remarks in,” he told me. So did many of his classmates. I’m not sure I would have done the same but, then again, why not learn to live with edits and criticism, with a few dozen pieces of marginalia?

“In many other classes, my work was either seen only by the professor or at the most, by other classmates,” said Prim Chuwiruch. “It never extended beyond the classroom’s walls.” Publishing her work on Medium, edits and all, “braced me to deal with different people with all sorts of feedback as a reporter now.”

When Carr posted his students’ work on Twitter, he did so with affection. Chuwiruch told me Carr “never really shared his thoughts on making work public, but I know he always stressed the importance of developing tough skin. One can only assume from there.”

The week’s theme, “The Holy Music of the Self,” comes from Descartes, and is a sort of parallel to the philosopher’s cogito ergo sum—“I think, therefore I am.” When a person listens to the holy music of the self, he identifies with the song in his head, the rhythm and melody and lyrics he knows best. Carr clearly loved this line, in part because he knew the risks it carried.

“People remember what they can live with more often than how they lived,” Carr wrote in The Night of the Gun. Carr’s book took its title from a memory of a bad night: an argument with a friend and fellow drug buddy that ended with Carr staring down a barrel. That memory was holy music, and Carr played it on repeat until he interviewed his friend years later, after Carr had cleaned up. When they got to the gun, the friend told Carr, “I think you might have had it.”

Many of the media innovations Carr wrote about in his “Media Equation” column are devices designed to loop the holy music of the self. “There are now vast, automated networks to harvest all that narcissism,” Carr wrote in January. Fitting, then, that Carr’s students would work on profiles of other people. When the holy music gets too loud, why not listen to someone else’s song?

Carr’s own holy music didn’t suit everyone. While I lived in New York, a colleague named Michael Massing published a critique called “The Two David Carrs.” There was the analytical reporter, Massing wrote, and then “another David Carr, one who is breezy, knowing, star-struck, and insidery.” As with many critiques of Carr, that piece establishes Carr’s bona fides before it singles out his shortcomings and then pegs him as inconstant. But, as with many critiques of Carr, there’s an idealized version of him between the lines, and we’re responsible for it. David Carr made himself a character in his own work, but so did we, and we attributed qualities to him that he wouldn’t have necessarily attributed to himself.

Before he wrote The Night of the Gun, Carr spoke with dozens of people about his inconstancy, people who corrected every faulty note he’d mistaken for gospel. I can’t imagine he always loved the song it left him with. But he sang it with grace.

Week Eight: “Voice Lessons”

I can be a fairly literal person, so “voice lessons” brought back memories of my elementary school lisp, lip-synching my way through middle-school chorus, and trying to dodge the microphone during high-school band practice. I’m pretty sure I stammered through my marriage vows and my friends and family are just too polite to tell me. “Try to sound more like yourself” seems more paradoxical than it does helpful. For me, writing something down—and taking the time to rewrite it, again and again—is less about using my authentic voice and more about trying to pin it down, and learning to live with it.

For his lesson on voice, Carr wrote that “who you are and what you have been through should give you a prism on life that belongs only to you.” Again, he dodged a few J-school standards in favor of more contemporary and less obvious readings. (And why not? Some of us have had quite enough of “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” thanks.) Instead, I read Camille Dodero’s profile of Adalia Rose, a six-year-old with progeria who became an internet celebrity, and Hamilton Nolan’s critique of Katie Roiphe.

Both Dodero and Nolan use their voices for criticism, but their approaches are different, and equally laudable. Dodero is empathetic. Rather than rage at the trolls who terrorized Rose’s family, she portrays Rose with dignity, enough to shame the people who bully her.

Where Dodero used thousands of words to subtly chastise her targets, Nolan took fewer than 500 to dismantle Katie Roiphe’s over-generalized and –simplified Newsweek cover story, “The Fantasy Life of Working Women: Why Surrender Is a Feminist Dream.” I wrote a bit recently about Roiphe’s work, which sometimes seems to confuse cultural analysis with deep reporting.

Read that last sentence again. See? That’s my voice—or, at the very least, the voice of the part of me that worries I’ll offend someone if I’m too direct. Hamilton Nolan, buoyed by the strength of his convictions, doesn’t have the same inhibition:

Katie, in the future, your rape fantasies should be presented in first person essay format rather than thinly-veiled-projection-upon-imaginary-ideological-opponents format.

Carr had his own secret codes. There’s his literal voice, of course, which Jeff Jarvis likened to “a badly tuned diesel engine struggling up a mountain against the wind.” And there’s the way he delivered his stories, which Emily Overholt told me was “the most bizarre speech pattern you’ve ever heard.” Here’s how Carr described himself (in third person) in his syllabus:

He is an idiosyncratic speaker, often beginning in the middle of a story, and is used to being told that people have no idea what he is talking about. It’s fine to be one of those people. In Press Play, he will strive to be a lucid, linear communicator.

I did most of my Press Play readings in the morning, before my wife and daughter woke up. Once they did, we’d have breakfast together, and then my wife would work for a bit while I took my daughter on a hike. Someone had seen a bear near our house earlier that summer, so we stuck to the gravel roads, though they were quiet as the forests, and the only noises were our own.

My daughter doesn’t really speak yet, but during our hikes she tried out the few single-syllable sounds she could make. I’d wear her in a carrier, strapped to my chest, and as I walked with her I’d describe the things we passed—a family of deer, a horse barn, the turkeys that lived in a nearby field. Sometimes, she’d see a deer before it hopped a fence and disappeared into the woods, and she’d make a soft, gurgled gasp. Once she was talked out, she’d fall asleep, usually with a mile or more to walk before we made it home.

When she was asleep again, I’d listen to interviews with Carr. This summer, On the Media ran an old segment by John Solomon, about editing sound for radio, where he played unedited tape from a Carr interview to demonstrate where a stutter had been removed. (“People have to speak in complete sentences or you—you—you—you don’t—you don’t use it.”) After he died, Fresh Air ran two interviews with Carr, from 2008 and 2011. In the first, Carr told Terry Gross that his fear of errors made him a restless sleeper. “After I’ve written something,” he told Gross, “I wonder if I got something right.” In the second, Gross described Carr’s voice (“a little raspy,” “a kind of hoarseness”) and asked him whether it had always sounded so.

I spent a lot of time thinking about how to describe the texture of David Carr’s voice. It could cheer and skip, or grumble and skulk.

“It sort of comes and goes based on the amount of fatigue I have,” Carr replied. “I could have surgery to remove the vocal nodes, but I’ve had a lot of surgeries… I have no spleen. I have one kidney. I have no gallbladder. I have half a pancreas. And the idea of sort of willingly allowing people [to] cut into me—I’m probably not for that. I’ll just deal with the hoarseness of the voice.”

I spent a lot of time thinking about how to describe the texture of David Carr’s voice. It could cheer and skip, or grumble and skulk. It seemed like a necessary part of the portrait. I listened to it throughout the summer and wrestled with how I might describe it; I typed and deleted the word “sandpaper” over and over. I thought about it while I hiked with my daughter. Every now and then, a car would pass us, raise a cloud of dust and rearrange the gravel I’d just walked over. I’d look at the dust and gravel, then the woods and the mountains, then the top of my sleeping daughter’s head, from which all her flawed and beautiful noises come, and think, “Maybe that’s it.”

Week Nine: “Distribution Models”

I went a bit overboard with the “voice lessons,” so I’m going to keep this short. Millions of people read Carr’s columns, and nearly half a million followed him on Twitter. He used his platform to promote work by his students—which is precisely the sort of generosity that made me (and everyone else) tweet at him and email him so he might promote my work. David Carr became a distribution model, and he did it by being a model distributor.

Week 10: “Beyond Clicks, a Look at Reader Engagement”

Tony Haile visited Carr’s class on Nov. 10, 2014. Haile, the CEO of web analytics company Chartbeat, wrote a feature for Time to dispel myths about how people engage with content online, and Carr gave it to his students. Here’s the upshot: People who share or click on articles don’t necessarily read them, and native advertising—which, as my colleague Dean Starkman described it, “seeks to become part of content that is itself defined by being separate, apart, independent”—won’t necessarily fool enough people to save journalism. (Haile doesn’t get into “branded content,” which seems to me like advertising that masquerades as something separate, apart, or independent.)

“It’s no longer clicks [companies] want,” Haile writes. “It’s your time and attention.” Elsewhere, Haile calls time “a rare scarce resource on the web.” Time is scarce on the web? Wait ’til he logs off.

Haile’s emphasis on time upset me because I knew what was coming. When Lillian Ross approached Ernest Hemingway about profiling him for the New Yorker, he replied in a letter, “Time is the least thing we have of.” It’s Nov. 10, 2014, and David Carr will die in three months, but he’s in his classroom, listening to Tony Haile with his students and hoping that they’ll make good work in what time they have.

And it’s a coincidence, and not at all linear, but here it is: My daughter was born the same day. Nov. 10, 2014. I’d spent the previous 24 hours next to my wife, watching her contractions intensify and her labor stall, holding her through some of the hardest work and most intense feelings a person can bear. After my daughter was born, just after 4 a.m., the three of us fell asleep together. When I woke up, it was light out, and work—good, honest work—was the only thing on my mind.

Week 11: “Telling Stories in a Visual Age”

The previous week, Carr’s students had pitched their final projects. This week, they brought what they had with them to class, to get feedback before they submitted their first drafts. With the exception of one student, a photojournalist working on a project about the ways in which Muslim men and women interact with American culture, every student was writing.

Carr’s guidelines for his students’ assignments boiled down to “impress me,” said Emily Overholt. “I don’t really care if you hit a homerun,” she recalled him saying. “I just care that you swing big.” Overholt’s final—an essay about her experience acquiring a gun license, set against statistics about gun sales and research into different state firearm policies—was a big swing. It didn’t connect as she hoped, but she told me that it was one of the first times she chose not to take an edit from Carr. Early in the semester, Carr had explained that students were free to ignore his feedback, but if they did, then they would be writing against the preferences of an experienced editor.

“There was a final moment where I chose not to take an edit, and I thought, ‘Wow,’” Overholt told me. “It was a really strange feeling.”

Though they may have had his voice in their heads, none of Carr’s students wrote like their teacher. They wrote critical essays about race and the cosmetics industry, and narrative stories about augmented-reality video games. One student, Cat McCarrey, wrote about the disappearing Shaker community, and her piece considers, with admirable subtlety, whether a faith can outlive its practitioners. I read them all, but the last one stayed with me most vividly. One of McCarrey’s interview subjects, Brother Arnold, told her about men and women who try to become Shakers and wrestle, alone, with their doubts and feelings of inadequacy. “Well, you know it’s just humanness,” he told her. “You always hope that people understand that and find that answer for themselves rather than you having to tell them.”

As students revised their final assignments, Carr gave them a break from readings. This week, he assigned three short documentaries, two of them by—wait for it—Vice.

Surprising, given that showdown between Carr and Shane Smith in Page One? Not really. Carr was a top-notch ethicist, but his ethics didn’t preclude him from studying how stories might be more effectively shared. “Getting a media message…into the intimate space between consumers and a torrent of information about themselves is only going to be more difficult,” he wrote in January. The Vice documentaries—a profile of a cannibal named Issei Sagawa, and a report on the food replacement Soylent, told through a combination of explanatory reporting with vlogging—have been viewed more than 11 million times.

Carr had warned students that “sharing” didn’t mean “reading.” But he also recognized that a few million shares or clicks represented some sort of new audience impulse, some raw material, which could be refined. And artists in every media might consider how to engage with that impulse.

“I’ve been around since before there was a consumer internet,” wrote Carr, “but my frame of reference is as neither a Luddite nor a curmudgeon. I didn’t end up with over half a million followers on social media—Twitter and Facebook combined—by posting only about broadband regulations and cable deals.” Maybe that’s what Massing meant when he called Carr “knowing.”

Ah, but Carr seemed to know that, too. “Not all self-flattering portraits are rendered in photos,” he wrote. “You see what I did there, right?”

Week 12: “Pitching for All the Marbles”

I can’t tell you David Carr’s secrets for successful pitches. I don’t know them. When I asked the students I spoke with whether I could look at their notes from the semester, most told me they didn’t keep any. I felt at a loss for words. So did my editor.

“Something about contemporary students and their lack of…something?” he wrote. He suggested a comparison to W.H. Auden and his students at the New School, who took such detailed notes that Auden’s Lectures on Shakespeare could be reassembled and, in a way, live again. Maybe someone will comb through the work on Carr’s red iPad, where he kept long lectures he’d read to his students. Maybe some exacting note-taker will emerge. Regardless, notes can’t really revive Carr any more than they can Auden.

Even if I had Carr’s secrets for pitching stories, my temptation would be to omit them from this essay, and try to forget them myself. Carr doesn’t seem like the sort of person who dealt in short cuts. In his syllabus, Carr said he was “rarely dazzled by brilliance” and called himself “a big sucker for the hard worker.” When a journalism student asked Carr, during a Reddit “Ask Me Anything” in 2013, for advice on how to succeed in journalism, Carr replied, “No one is going to give a damn about what is on your resume, they want to see what you have made with your own little fingies.”

I can tell you that Carr offered to help his students get jobs by testifying to their intelligence and hard work. And I can tell you that a good number have journalism jobs that allow them to further their intelligence and work even harder. Carr’s TA, Mikaela Lefrak, works for The New Republic. Prim Chuwiruch works for the Boston Courant. Clinton Nguyen works for Vice’s Motherboard. Emily Overholt chases stories for the Associated Press—the sort of job Carr warned her might feel like “shoveling coal,” generating so many stories so quickly.

“I thought, ‘I’d love that,’” Overholt told me. “Here I am, shoveling coal.”

After she took a leave of absence from school, to work in the Boston Globe’s co-op program, Brooke Jackson-Glidden returned to Boston University. She currently contributes to the Globe and Boston Magazine, where she is an intern. Jackson-Glidden’s first big story for the Globe was a profile of Lena Dunham, who sent Jackson-Glidden an email in January that read, “D. Carr said you’re looking for me and won’t abuse my email.” After Carr died, Dunham tweeted:

Jackson-Glidden told me she heard from Dunham again after Carr’s death. “Our man is gone,” Dunham told her. “Sweet sweet brilliant DC. He adored you.”

Week 13: “The Unveil”

Finals week. Show me what you’ve made with your fingies.

Week 14: “So What Have We Learned?”

(Link)

Ta-Nehisi Coates met David Carr in 1996, when Carr hired Coates to work at the Washington City Paper. At the time, Coates was 20 years old. He was a Howard University student, but wasn’t taking classes that semester.

Carr ran his newsroom like a classroom. He photocopied magazine articles for his reporters and gave them books—Sims & Kramer’s Literary Journalism anthology, Sherwood & Jaffe’s Dream City, Joseph Mitchell’s Up in the Old Hotel. Coates called Carr his tutor in the art of “argument by reported narrative,” the genre in which Coates has written some of his most effective, impactful work, including “The Case for Reparations,” which Carr made his students read. After “The Case for Reparations” won the George Polk Award for Commentary, Coates wrote at the Atlantic that the award was “the property of David Carr.” Coates also dedicated his new book, Between the World and Me, to Carr. And then the day his book was published he tweeted:

I miss @carr2n terribly right now.

— Ta-Nehisi Coates (@tanehisicoates) July 14, 2015

Teaching, said Coates, seemed natural to Carr, and Boston University had afforded him the opportunity to do it more often. “He’s always been big on young people,” said Coates. “He didn’t say this to me, but I think he liked interacting with young people about the craft.”

Carr cherished his young students the way they cherished him. Chuwiruch told me that she’d texted Carr when she and her younger sister took a trip to New York. Carr invited them to the Times Building, gave them a tour, had coffee with them, asked about their plans. “He was just really curious about our lives,” said Chuwiruch. For the rest of their New York visit, Chuwiruch got texts from Carr—what to do, where to go.

After Carr died, reporters converged on the students in his class. One told me it felt like a class-wide conversation through obituaries. Overholt said, “It was really kind of exhausting.” Brooke Jackson-Glidden watched Page One for the first time, and told me, “It was lovely to be able to see him again.”

Boston University asked Coates to teach Carr’s media criticism class for the rest of the semester, and Coates accepted. Teaching the class, he told me, was “incredibly emotional.”

“It was surreal,” he said. “I thought about him all the time. I felt bad for the kids because they got cheated.” So, each week, Coates shared a story or two about Carr with his students. “None of which,” he told me during our interview, “are coming to mind right now.”

Carr taught Coates to approach narrative with humility, and to use it to its most powerful effect. Here, then, was an equally powerful testament to Carr’s teaching, from a student who had known him for nearly half his life. No stories but silence. Over the phone, I listened to the sounds of traffic on the street of wherever Coates had called from.

Later, I wondered about his response. Coates spoke with me during an exceptionally busy week. Between the World and Me had been published days before our conversation. It seemed believable that Coates was incredibly busy, that the stories about Carr simply wouldn’t come to mind. But maybe Coates, like many of Carr’s students, decided to keep those stories private. When I asked him what Carr’s hopes for his students and other young journalists were, Coates replied, “Go out there and kick some ass.” I asked him another version of the question later, hoping for more, and Coates stuck to the same answer. He had already written a tribute to Carr in February, and shared the stories he wished to.

I also wondered about my own response. I didn’t ask the follow-up, didn’t press Coates for more, and so if there’s something lacking here, then I’m to blame. But there would have been something lacking here anyhow, as there is in any profile, whether the subject is alive or dead. I can’t recreate David Carr’s holy music. I wouldn’t know where to begin.

“Go big or go home”

—Carr’s email signature during his days at the Washington City Paper

For his “Voice Lessons” unit, Carr wrote to students, “ending stories with a quote from someone else is often the coward’s way out.” That’s a shame, because I had mine all lined up. The day Jackson-Glidden went to Carr’s office to confess her insecurities, he confessed his own.

“You never feel like you’re good enough,” he told her. “And that’s how you know you are.” Wouldn’t be a bad way to end, would it? And why not give him the last word?

But I wouldn’t be working very hard if I left you there, would I? And Carr didn’t champion cowards and slackers.

Carr didn’t live long enough to write a farewell column in which he hovered over the vast body of his work and told us what it all, ultimately, meant. Instead, the New York Times (which recently announced a fellowship named for Carr) published sections from Carr’s Press Play syllabus. One of his colleagues wrote that the syllabus showed Carr “in his purest form — at once blunt, funny, haughty, humble, demanding, endearing and unique.” The column quoted a few of Carr’s students, and detailed Carr’s reading list; it even singled out “Consider the Lobster,” which I found funny, considering Carr and his students skipped it.

Tony Haile was right when he called time a “rare scarce resource.” There could never be enough time for Carr to tell us everything he wanted to. What we’re left with—and let’s strike that existential chord now—are the stories Carr shared with his students.

Are those stories enough? I doubt it. Writing about Carr feels to me, finally, a lot like taking his class. Carr tracked the evolution of journalism and its practitioners, their steps and missteps and his own. He provided students with his own exquisite perspective on how news is made today, and might be made tomorrow. But his stories are, by their nature, incomplete.

“Journalism and teaching are both acts of transmission,” my wife told me, when I told her that I didn’t know how to end this properly. And those acts can be noble, selfless, revelatory. But we misinterpret them, or fail to take notes, or simply forget them.

Certainly Carr knew this and tried to impart it. Go back to Week One, to Alexis Madrigal’s essay. There’s a balance, Madrigal wrote, and then there’s an edge. A structure and an end. In that sense, Carr could never tell a complete story. Neither can I.

But that didn’t keep him from trying. Which is perhaps why I find his final lesson most instructive: On the night he died, David Carr was simply going back to work.