Remember the General Slocum

The morning of June 15, 1904, promised a day of fun for more than a thousand residents of the Lower East Side. In an instant, it turned deadly.

Walk with me: left out of my building on East 89th Street, straight across East End Avenue and into Carl Schurz Park, up the stone stairs, past Gracie Mansion, and down the broad and curving pram steps to the benches that face the river. Sit down. It’s peaceful here, with the ruffled waters of Hell Gate spread before us, the big Siberian elm casting its shade over the path, a few gulls circling, maybe a cormorant diving near the seaweed-covered rocks below. The whoosh of traffic on the FDR Drive is muted, invisible underneath the park; across the water, cars flash along the span of the Triboro Bridge, too far away to hear.

One hundred and six years ago today, just before 10 o’clock on a morning of glorious sunshine, the paddle-wheel steamboat General Slocum churned into view just in front of where we’re sitting. As long as a city block, her three tiers of open deck were dazzling in a fresh coat of white paint. A band was playing gaily on the topmost deck, and more than a thousand holidaymakers thronged the rails, all in their Sunday best, even though it was a Wednesday. For their much-anticipated annual Sunday School picnic, the parishioners of St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church on East Sixth Street had chartered a cruise from the Third Street pier to Locust Grove, out beyond Oyster Bay on Long Island Sound.

Being that it was a workday, the passengers were mostly women and children; being that they came from St. Mark’s, they were mostly German immigrants. In 1904 their Lower East Side neighborhood was still known as Little Germany, though the promise of cleaner streets and better amenities had already lured many of their more successful neighbors uptown to the fast-growing German enclave of Yorkville.

As the General Slocum passed the lighthouse at the northern tip of Blackwell’s Island—now Roosevelt Island, which you can see from our bench if you look to the right—a little boy tugged at the sleeve of a deckhand. “Mister, there’s smoke coming up one of the stairways.” Yeah, sure there is, thought the deckhand, but he went below to check as the boat veered gently to starboard past Ward’s Island, and the pilots concentrated on the tricky currents of Hell Gate.

When roll was called at P.S. 25 on East Fifth Street the next morning, 51 children were missing.

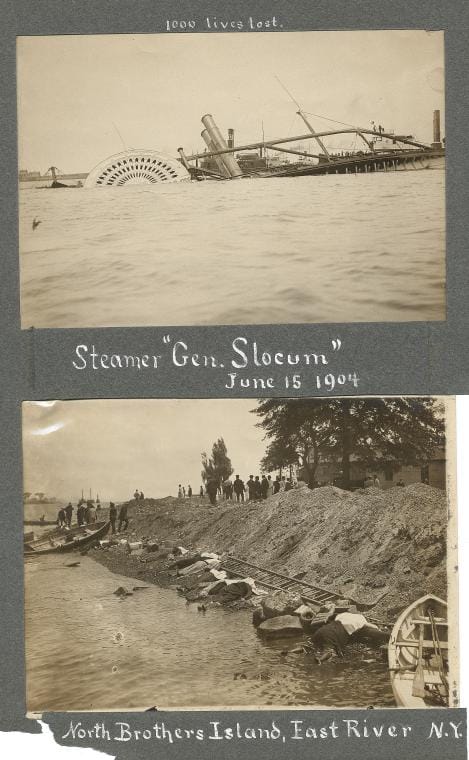

Seven minutes later the voice of the first mate thundered up through the speaking tube into the pilothouse. “The ship’s on fire!” As the captain emerged he was driven back by a wall of flame. Retreating into the pilothouse, he ordered the ship full steam ahead, aiming for North Brother Island off the Port Morris section of the Bronx, just a mile away. When the blazing ship hit the beach, the top two decks collapsed.

More than a thousand people died that day. The captain’s decision to speed straight into the wind instead of pulling toward a Bronx pier fanned the flames. The General Slocum was constructed entirely of wood. The aging firehoses on board burst when the water was turned on. The lifeboats, it turned out, had been wired to the deck and glued down with each season’s new coat of paint. The life preservers were more than a dozen years old; the cork inside the tattered and brittle canvas covers had disintegrated. Terrified mothers strapped the useless vests onto their children, threw the little ones overboard, and watched in horror as they sank. A blanket of sodden cork dust spread across the water. Waves of jumpers landed on top of those who had jumped first, pushing them under, and the towering 31-foot paddle wheels bore down on the bodies in their path. Those lucky enough to know how to swim were in danger of being dragged down by the panic of the drowning.

Ignore the thumping of the helicopter overhead. Screen out the Triboro with a hand to your brow. Focus on the water as it swirls, just as it did a century ago, at the tidal convergence of New York Harbor and Long Island Sound. For most of the General Slocum’s city-dwelling passengers, water was just as frightening as fire. Until Sept. 11, 2001, the date of the city’s deadliest tragedy was June 15, 1904. In the days following both events, desperate survivors and relatives searched the city, carrying photographs of the missing.

Today the General Slocum is all but forgotten. The victims came from a single neighborhood—few New Yorkers were involved directly. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire seven years later, with its epic backdrop of class struggle, eclipsed the tragic Sunday-school outing as the city’s most infamous blaze. The outbreak of the First World War a few years later provoked a lasting wave of antipathy for all things German.

Seven decades after that fateful excursion my mother’s sister married a man named Slocum, the great-great-grandnephew of Major General Henry Warner Slocum, West Point alumnus, Union Army commander, lawyer, and U.S. congressman from Brooklyn. General Slocum died in 1894, three years after they named a steamboat for him. There’s an equestrian statue of him near the entrance to Prospect Park. It was unveiled on Memorial Day in 1905, less than a year after the boat bearing his name burst into flames.

Six hundred and twenty-two families lost relatives on the General Slocum. Half of the congregation of St. Mark’s Church died. By Memorial Day 1905, more than a quarter of the stricken families had left the neighborhood. By the end of the decade, Little Germany had largely ceased to exist, and thousands of Eastern European Jews had moved in.

Sometime shortly before 1910, my teenaged great-grandfather, a Galician Jew, landed at Ellis Island. A baker, he got married and raised three children at 168 East Second Street, a few blocks from St. Mark’s. Perhaps the previous tenants of his tenement apartment had been parishioners. St. Mark’s shut its doors in 1940, and reopened soon after as a synagogue. The remnants of the congregation merged with Zion Lutheran, on East 84th Street in Yorkville.

We’re sitting in Yorkville now. It’s no longer particularly German. But the Upper East Side, of which Yorkville is the easternmost part, was home to more victims of the Sept. 11 attacks than any other Manhattan neighborhood. Another catastrophe that unfolded on a gorgeous day. Remember the General Slocum today, and ponder the currents of history that are part of the view from one park bench.