Right Here Waiting

After frequenting a local haunt where nobody knows his name, a Chicago writer makes new friends, rips on Richard Marx online, and then suddenly lands a real live celebrity musician at their door.

The Lighthouse Tavern occupies the bottom floor of an apartment house in Rogers Park, a neighborhood that is—both geographically and metaphorically—the attic of Chicago. Situated on a block that dead-ends into Lake Michigan, where a sign warns the city can’t be responsible for cars swamped by dangerous waves, the Lighthouse is the kind of place you discover—not as de Soto discovered the Mississippi, by following a trail of rumor, but by walking past its door for the dozenth time and realizing, “Oh, there’s a tavern behind there.”

When I discovered the Lighthouse, there was no sign outside, just a glyph of a glowing beacon on the maroon awning. The only beers on tap were Old Style and Miller Lite. Behind the bar was a framed photo of Bears coach Mike Ditka flashing the finger—the essential artistic adornment for any true Chicago tavern. The average age of the patrons was dead. At one time, Rogers Park had been an Irish and Jewish neighborhood, but immigration and suburbanization transformed its demographics to equal thirds white, black, and Latino, with a few Middle Eastern grocers mixed in for diversity. The Lighthouse was the last redoubt of white folks too sentimental—or too broke—to leave the old neighborhood. Sitting next to the stubborn ethnics on the torn vinyl stools were broken, drunken men and women who lived in adult care facilities on Sheridan Road, the neighborhood’s main drag. As an early-middle-aged transplant to Chicago who had lived in Rogers Park only a dozen years, I didn’t really fit in at the Lighthouse, but draft beer was a buck-fifty, and on Chicago Bears Sundays, the bar put out a picnic spread of fried chicken, potato salad, cole slaw, and rolls. When I drank, I usually sat alone at a table by the jukebox, reading paperbacks from the lending library. My profile was so low that when I walked into the Lighthouse to watch Super Bowl LXIV, the bartenders stopped selling $5 squares for the football pool. They thought I might be a Fed.

After that incident, I decided to step up my Lighthouse game—to drink there once a week until all those career alcoholics at least stopped looking at me with suspicion. But then the octogenarian owner died, and three guys half his age bought the bar. They were all graduates of the neighborhood high schools, but they were members of my generation, and I never saw them dragging wives around. That was a brotherhood I could crack. I had misspent a good portion of my 30s as one of the bachelors who bet on horses at Arlington Park. “You have an affinity for seedy male subcultures,” a friend once told me.

“What happens when two Irishmen and a Jew buy a bar?” I asked Jason, one of the new owners and the odd man out in that joke.

He thought for a moment, then exclaimed, “They drink the beer, and I count the money!”

I was like one of the background extras on Cheers. Even that, I was ambivalent about.

The new owners bought new barstools, got rid of the Ditka photo and the maudlin display of Mass cards from regulars’ funerals. They added craft beers to the taps and scheduled jazz combos and bar trivia nights. Despite their efforts to make the Lighthouse appealing to people who don’t yet need to substitute alcohol for any remaining hopes of money, fame, or sex, a local website named it one of the 25 least douchey bars in Chicago.

I started drinking there often enough for everyone to know my face, but I wasn’t one of the Lighthouse All-Stars. Not like Randy, the shaggy 51-year-old who could drain half a dozen pints while watching a golf tournament and whose vocabulary became more complex and erudite the more he drank. Or Vinko, Croatian mailman to the stars, who entertained us with stories of delivering mail to Michael Jordan and Billy Corgan. Or Even Bigger Sexy. He was six-foot-eight, so you had to notice him. I was like one of the background extras on Cheers. Even that, I was ambivalent about.

“I used to worry that I didn’t fit in at my local bar,” I told a friend after spending a boisterous evening drinking with Vinko and Mike, a plumber who co-owned the Lighthouse. “Now, I worry that I do.”

I write a news blog for a local TV station, which requires me to have opinions on topics I know nothing about. I don’t know anything about music, but I know what I don’t like. And I didn’t like “See You in Chicago,” the city’s new tourism theme song performed by Buddy Guy, Umphrey’s McGee, and Chicago. The track combined every local music cliché: a guitar solo from an electric blues album, horns from Chicago IV, synthesizers from Chicago XVII, vocals inspired by Billy Corgan, and lyrics from a Richard Marx song. Mixed together, they sound like the B-side to the theme from an ’80s John Hughes teen comedy.

As I wrote in a review of the song on my blog:

Every one of these musicians has performed outstanding work on their own, but together, they’ve produced a power anthem that would have embarrassed Damn Yankees, The Outfield or White Lion. (But not Richard Marx. Richard Marx is shameless.)

Just like all the other snotty remarks I make about local celebrities, as soon as I posted it I forgot about it. My blog has a readership in the mid-three figures, so naturally I assume no one notices what I write. The next afternoon while at Naval Station Great Lakes for my sister’s stepson’s boot-camp graduation, I received an email with the subject line, “From Richard Marx.”

Edward,

How exactly am I “shameless?”

Do you know me? Have we met?

You print a statement like that in my home town, you better have a reason and I’d like to know what it is.

Richard Marx

“Wow,” I told my sister. “Richard Marx is blowing up my inbox.”

Until I wrote that blog post, I hadn’t thought about Richard Marx in more than 20 years. Back in 1989, my friend Marty was trying to describe the roster of a celebrity softball game, but couldn’t come up with the name of one of the musicians.

“Who’s that guy who really sucks?” Marty asked.

I knew immediately. “Richard Marx?” I replied.

Marty’s face lit up. “Yeah! That’s it!”

At that age, I don’t think I could have liked Richard Marx even if I’d liked his songs. I was too much the angry contrarian to listen to the same music as people who went to the prom. I didn’t even like REM—all their fans were in the Honor Society.

In the 1980s, my most memorable concert experience was hitchhiking to a Dead Kennedys concert in Detroit. Richard Marx—author of the 1980s pre-prom ballad “Right Here Waiting,” the 1980s prom ballad “Hold on to the Nights,” and the 1980s post-prom ballad “Endless Summer Nights”—was not just far outside my musical tastes, I thought he was ear cancer. I was convinced Richard Marx was a poor man’s Kenny Loggins who had written “Hold on to the Nights” after consulting with a marketing team who told him the cassingle could be sold to 18-year-olds at tuxedo rental stores and dress shops. At that age, I don’t think I could have liked Richard Marx even if I’d liked his songs. I was too much the angry contrarian to listen to the same music as people who went to the prom. I didn’t even like REM—all their fans were in the Honor Society.

My sister graduated from high school in 1992, so she’d been even more afflicted with Richard Marx’s music than I was. We looked up him up on Wikipedia and found out he lives in Lake Bluff, a 10-minute drive from the graduation ceremony.

“Maybe I should offer to stop by his house and explain,” I said.

We laughed it off, and I figured the email was just one of my few hundred readers messing with me. Why would someone who sold 30 million records care what a TV station blogger says? Then on Sunday I got this email:

No explanation for why you write that I’m “shameless?” You act pretty tough sitting alone in your little room behind your laptop.

If you’d written you hated my music, that’s cool. Like I could give a shit. But saying I’m “shameless” calls into question my character and integrity.

This is my hometown…where my kids live…where my mother lives…and this will not stand with me.

Would you say that to my face? Let’s find out. I’ll meet you anywhere in the city, any time. I don’t travel again until the end of the week. Let’s hash this out like men.

Never heard of you in my life before, but between various columnist/radio friends and an array of people at NBC, I now know plenty about you. You don’t know anything about me. But you’re about to.

This isn’t going away.

Richard Marx

I called my editor.

“I’ve been getting emails from some guy who says he’s Richard Marx,” I said. “I think it’s an impostor. The only thing that makes me think it might really be Richard Marx is that it’s from an AOL account.”

My editor had been a waiter at a pizzeria in Lake Bluff, where Richard Marx ate with his family.

“He was a terrible tipper and a real douche,” my editor said. “We used to argue about who had to serve him. His wife is taller than he is.”

(According to Wikipedia, Richard Marx married a singer/dancer/actress who performed in the “Don’t Mean Nothing” video.)

The next day, my editor told me he’d traced the emails to a MySpace account with the same tag.

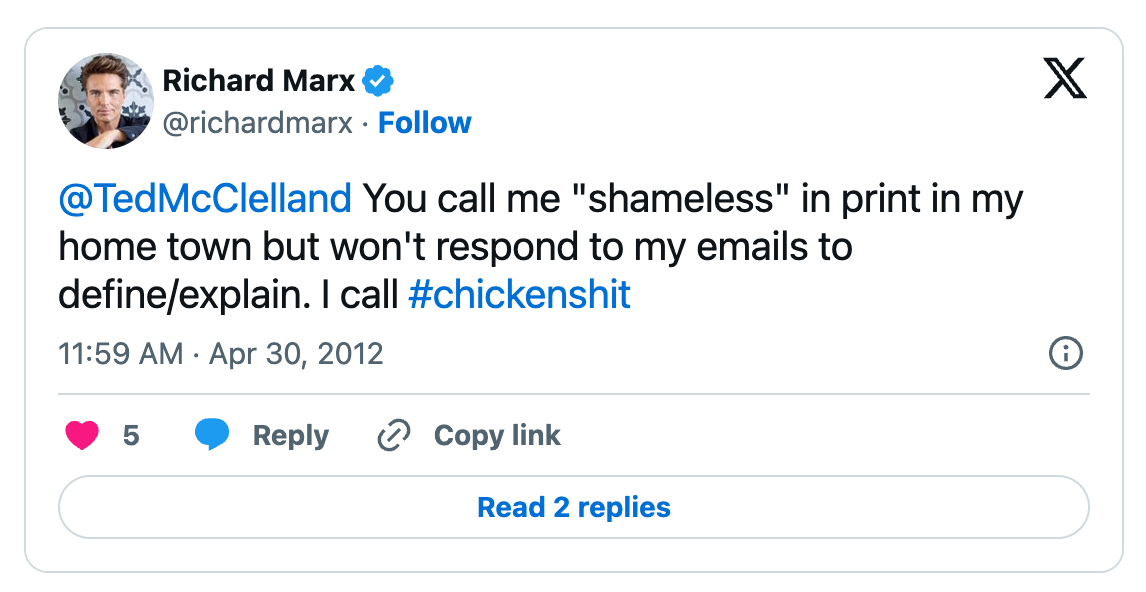

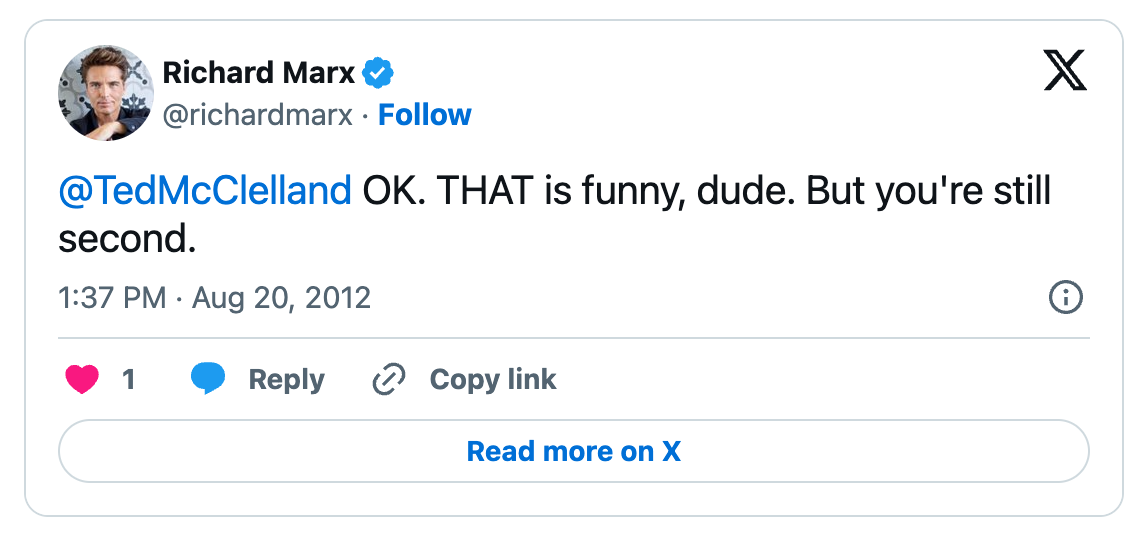

Except the emails hadn’t been coming from a guy with a MySpace account. They were actually from Richard Marx. How do I know? Because I received this tweet from Richard Marx’s verified Twitter account:

It was followed by this tweet:

“Richard Marx is totally calling me out on Twitter,” I told my editor.

“Just ignore it,” he said. “It’ll blow over.”

“I’m not going to ignore it. I’m not going to look wimpier than the guy who wrote ‘Right Here Waiting.’ He says he’ll meet me anywhere in the city.”

And besides, my life was a roundelay of the spare bedroom in my apartment, which I used as an office, the grocery store, and the Lighthouse. I needed some excitement.

So I emailed Richard Marx, inviting him to meet me at seven the next evening at the Lighthouse. Then I went down to the bar to prepare the boys for Richard Marx’s arrival. I wanted a posse behind me when he walked in the door. Vinko and Paddy, our token Irishman, were sitting at the end of the bar, next to the beer cooler. We looked up Richard Marx on Billy the bartender’s laptop and starting slagging him.

“You should send him an email and tell him you’ll be right here waiting for him,” Paddy suggested.

“We should do one of those rock ‘n’ roll cage matches,” I said. “Marx and Lennon. Richard Marx versus John Lennon.”

“He’s not going to show up,” said Vinko, after mentioning that he’d delivered mail to Richard Marx’s father, a jingle writer who wrote the Chicago Blackhawks theme song and had grown up in Rogers Park, when it was still Jewish. “What’s he got to gain out of it? I’ll bet he doesn’t come here tomorrow night.”

Regardless, I had to be there or lose face. I worried this might be a trap, that Richard Marx was going to send a process server so he could sue me for libel. He could afford to outsource his honor to lawyers.

I got to the Lighthouse an hour early. By 6:45, I had half a dozen guys behind me: Vinko, Paddy, Billy, Aquaman, Brian, and Mike. Nobody wanted to miss Richard Marx. By 7:15, Billy had left the bar, convinced Richard Marx wasn’t going to show.

Then someone spotted a black Jaguar rolling down Chase Ave. I looked out the window. Billy was walking back up the street, alongside Richard Marx. I had steeled myself for this confrontation by drinking an entire pint of light beer. Richard Marx didn’t get two steps past the door before a guy at the bar stuck out his hand and said, “Hey Richard, good to see you.” I waved to let Richard Marx know I was the guy who had called him shameless.

Richard Marx sat down next to me. We shook hands. He was wearing skinny jeans and a leather jacket. His black hair was combed in a pompadour. I don’t think he’s had a face-lift, but his skin looked like Silly Putty shaped over his cheekbones. He reminded me a little of Rick Springfield or David Cassidy—pop stars who try so hard to avoid aging they end up looking like bony versions of their youthful selves.

“Explain to me why I’m shameless,” Richard Marx said.

Had I given it more thought, I would have written that Richard Marx was the kind of musician who wouldn’t be ashamed to record anything he thought would sell a million copies. But I didn’t want to say that to his face.

“Listen,” I said. “If anything I wrote offended you personally, I apologize. It was meant to be a musical criticism, and I don’t think any reasonable reader would have taken it otherwise. I didn’t intend to impugn your character.”

“How is it anything other than personal when you call me shameless?” Richard Marx said. Then he asked, “Do you have any children?”

“No,” I said.

“Well, then you can’t relate. You called me shameless in my hometown, where my family can read this.”

That was a douchey thing to say, especially since Richard Marx is married to a model and I’d woken up alone that morning. I let it pass, though. I wasn’t there to start another argument.

“You need to have a thicker skin,” I said. “People write things about me on the internet all the time.”

“Nobody has a thicker skin than I do,” Richard Marx said.

“Have you ever confronted a writer before about something he’s written?” I asked him.

He said he hadn’t.

“So, why are you doing it now?” I asked him. “I’m not anybody big. I’m not Rolling Stone or the LA Times.”

“It’s in my hometown. And it’s on NBC. How much do you know about music?”

“I don’t care if you criticize my music. There’s nothing more subjective than music.”

“I’m not a music critic,” I said. “That’s not the theme of my blog.”

“How much do you know about my music?”

“I know what I heard on the radio,” I said. “I have to admit I’ve never owned one of your CDs. I was listening to punk rock in the 1980s.”

“Fair enough,” he said. “I don’t care if you criticize my music. There’s nothing more subjective than music.”

I reached down for my satchel. I’d promised in my email that if he showed up at the Lighthouse, I’d give him a copy of a book I’d written about the president.

“Do you like Barack Obama?” I asked Richard Marx.

He made an irritated face. I pulled out the book and handed it to him.

“I don’t like your blog,” he said. “Why would I like your book?”

“Well,” I said, “this is me when I sit down and am more thoughtful than I am when I’m blogging.”

So Richard Marx accepted the book and then posed for pictures with several young women before walking back to his Jaguar. As soon as he was out the door, everyone in the bar began post-gaming the showdown.

“When I put my hand on his back to pose for picture,” one of the young women said, “he was trembling.”

“I gotta say,” Vinko offered, “the guy’s got balls to walk into a strange bar in a strange neighborhood all by himself.”

Mike was less impressed.

“Why couldn’t you have insulted someone cool?” he asked me. “Like Iggy Pop or Keith Richards?”

The summit with Richard Marx made me a Lighthouse All Star, at least for that night. A young woman who had never spoken to me before showed me a photo she’d taken of my conversation with Richard Marx, and she touched my chest while doing so. When I returned to the bar that Friday, Paddy and Vinko cheered as I walked through the door.

“Shameless Ted!” Vinko shouted.

Nothing marks you as a regular like a nickname. On the chalkboard behind the bar someone had written, “Lighthouse Tavern wants to thank Richard Marx for stopping by.”

Vinko tried to come up with other celebrities I could insult on my blog. The boys had been touched by their encounter with celebrity and wanted more.

“Hey, Ted,” he shouted, trying to get my attention. “Ted! How about Billy Corgan? He’s on my mail route. He lives in a house on the lake. You can’t even see it from the road.”

I never thought of Richard Marx as a top-tier celebrity. He’s probably famous enough to get on The Surreal Life or I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here, but not famous enough for Dancing With the Stars. He was, however, the most famous human being ever to walk into the Lighthouse Tavern. The only famous human being, I’m sure. Such is the power of even Richard Marx’s celebrity, especially in the context of a neighborhood tavern, that it is transferable to anyone with whom he comes in contact. Richard Marx’s celebrity can generate a homunculus celebrity. In the small society of my local bar, everyone knows me as the guy who brought in Richard Marx. It’s not how I imagined being famous, but at least people won’t stop betting on the Super Bowl when I walk in the door.

After that evening, my only contact with Richard Marx was over Twitter. After Todd Akin said women couldn’t be impregnated during a “legitimate rape,” Richard Marx tweeted, “Todd Akin just jumped to the front of the line of faces I’d most like to punch.” I retweeted it, with the word “Whew!” in front.

So Richard Marx hasn’t forgiven me. Which is fair, because I haven’t changed my opinion of him either. A few months after visiting the Lighthouse, Richard Marx released a Christmas album. With Kenny Loggins. Available exclusively at Target. Maybe it’s easy for me criticize sellouts because I have nothing to sell myself, but when I told Mike the Plumber about Richard Marx’s latest release, he agreed.

“A Christmas album?” he said. “At Target? You know, I was kind of ehhhh on what you said about him”—Mike lifted his palm to chin level and wobbled it back and forth—“but that is shameless.”