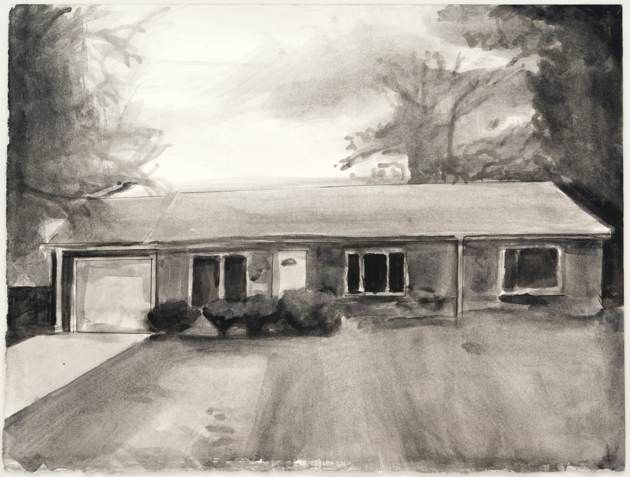

We were new then, living in new, too-big houses with too-small yards, the planted grass still looking like fresh hair plugs.

For the most part, we were Gen-Xers, our basements littered with guitars and amps, back issues of indie publications we’d once written for. None of the men had long hair anymore, although some of the women still favored the sort of chunky shoes they’d worn in college and grad school. We all had, or would have shortly, little kids who would draw on the sidewalk with fat stalks of chalk and jump in the mud puddles on the road that was not yet paved. They would have to be taught to stay out of the drainpipe with the big child-murdering drop-off, how to share (or politely not share) their belongings with the other children, and figure out which adults could be called by their first names and which required a Mr. or Ms.

We were in our first marriages, or second, the first ones having taken place in the distant past. We shared dinners in the common area, big potluck feasts for which someone always brought fried chicken. We’d drink at each other’s houses, where we’d compare the small details—the kitchen backsplash, the paint colors, the cherry or maple cabinets—that differentiated them. We’d all go in for pizza on Halloween; later we’d dole out miniature chocolate bars and drink beer on our porch steps, dropping the empties into identical recycling bins that we regularly stole from each other without malice.

Just as we never realized that we were new, we didn’t realize that we were becoming less new as the years wore on. We had more children, and one of us would make a schedule of dinners to be delivered after the births. We logged more time in our careers as professors and engineers and insurance agents and doctors and editors, and we took our leaves, either as sabbaticals or time off to care for the children. Some of us came into money and moved away. A few single mothers moved into those houses with their children. Some of the men started losing their hair and some of them preemptively shaved their heads. Some of the women grew plumper; some grew thinner. Some of us gave up drinking. Some of us ramped up our alcohol consumption. The children grew and graduated from their Montessori or international preschools and went on to public school. We were glad not to have to drive them as much.

There were skirmishes, of course, hurt feelings that had to be smoothed over and some agreeing to disagree, but for the most part, we had consensus. There was something creepy about the guy who lived adjacent to the neighborhood, the one who once filed a police report on one of our eight-year-olds. The dogs shouldn’t be allowed to crap where the kids play. A community garden would be lovely.

We’d known that there had been trouble between Nina and Ronald ever since last year when Nina discovered that Ronald had been engaging in a cliché of modern mid-life: a Facebook affair. They broke the news to us separately, Nina first, visiting us in tears while the kids were at school. Ronald would come by later, saying, “Let’s talk about the elephant in the room.” We obliged, although we refrained from pointing out to him that he was the one who led the elephant into the room. A few of us started thinking of the mistress as The Elephant, although, from what we saw of her Facebook headshot, she just looked like a trashy version of Nina.

Ronald would come by later, saying, “Let’s talk about the elephant in the room.” We obliged, although we refrained from pointing out to him that he was the one who led the elephant into the room.

Nina and Ronald reconciled until it came to light, one day before their family vacation, that he hadn’t broken it off with The Elephant after all. Nina went ahead and took their children to the beach—each meal out, she told us later, would start with a wrenching “Just the three of you?”—while Ronald packed his belongings and decamped to a basement apartment.

We were saddened and shaken. We liked both Nina and Ronald. They seemed to get along so well! Pretty Nina, with her easy laugh and almost comically efficient organizational skills, athletic Ronald with his wit and willingness to rap at our karaoke parties. We gave our own partnerships a thorough once-over and, after the lights were out, we’d seek our partners’ hands under the sheets, lace fingers, and whisper, “We’re OK, aren’t we?”

We were accustomed to the seeing the ex-husbands of the single mothers among us as these fathers loaded their children and their belongings—an overnight sack, a special pillow, various sports paraphernalia—into their cars, which were never minivans. We couldn’t quite remember their names (Rob? Tom?), but we were friendly nonetheless. We assumed Ronald would become one of those men, someone to whom we’d give a friendly wave or with whom we’d engage in some small talk as he ruffled his children’s hair. This is how a modern divorce was done in our generation: with civility and an expectation that, while the parents no longer lived together, the children would have plenty of access to both of them. We were a little smug about this. Enough of us had been children in Boomer divorces, witness to painful and embarrassing spectacles: the public shouting matches, the wardrobe on the front lawn, the bad-mouthing of “your mother” and “your father.”

Meanwhile, Nina was having a hard time talking. She’d respond just fine to a text or an email, but a phone call was rough, and in-person visit required a box of tissues. A week or two after Ronald’s departure, she emailed the women. She said she was ready to talk about it.

We scrambled to see who had an available house that night, whose family could be ushered out for the evening. It was late summer then, past the prime season for catching fireflies in the dark, but bedtimes were still lax. One of us came through with an open house, and the women traipsed over after dinner, our hair still smelling of sautéed onions or spaghetti sauce. We carried wine and beer. One of us carried a full pack of cigarettes that others of us would filch, hiding from the sightlines of the children.

We found seats in the living room, so similar to our own, with the white baseboards and gas fireplace. We were uncertain how to proceed, uncertain what Nina needed from us. The last thing we wanted to do was to make her feel foolish, which already goes with the territory of infidelity. For the first time in a long time, we were dealing with something new.

We chitchatted for a while until we got sufficiently drunk to start with the real talk. Nina started the tale. Like all cheating stories, it was a familiar one, the differences only in the specifics. The Elephant had left her own husband a year ago for Ronald. While Nina and Ronald had been reconciling, The Elephant had had her friends call the family home to plead with him to speak with her. Appalled by her ballsiness, we came up with unkind nicknames for her; she had a last name that begged for lewd puns.

We don’t think of him often, but when we do, it’s as if he’s dead. We can’t quite believe he’s still out there somewhere, playing basketball with a different group of men.

But then Nina laid this on us: Ronald told her that he’d be moving across the country in a few months. To where The Elephant lived.

Up until that point, we’d all been weighing our words, mixing our outrage and support with carefully chosen memories that didn’t denigrate Ronald and didn’t convey that somehow we’d known all along that he was an ass. We didn’t want to think this of him. We aspired to be the Friends of the Modern Divorced Couple, the people who did whatever was the divorce equivalent of bringing the casserole to the new parents.

But as the details emerged—Nina had to talk him out of telling their children that he was moving to be closer to “family”!—we felt the room shift. We didn’t want to believe this of Ronald any more than Nina did, but there it was. Ronald was pursuing a Boomer-style divorce, complete with semi-estrangement from his flesh and blood, the very thing that some of us had had to reckon with, or not.

When one of us posted on Facebook the next day, “I love my neighborhood!” Ronald commented, “I miss my neighborhood.” No one responded. We were a tolerant people, accepting differences in politics, religion, marital styles, child-rearing techniques. But when it came to leaving the children’s daily lives to pursue a romance with unpalatable origins, we agreed, without even speaking, to an old-fashioned shunning.

We returned home that evening and quizzed the men on what they thought. Nothing could surprise them. “He left a perfectly good family,” one of the men said, implying that given that decision, whatever bad decisions Ronald would make were pale by comparison.

We supported Nina in the ways we could, offering job contacts, dinner and drinks on Friday nights, our service as witnesses in the divorce hearings. We supported her decision to go for more than half of the marital assets, although hearing a lawyer yell, “Objection! Hearsay!” nearly brought us to tears. Slowly, the Friday nights became less about Ronald and more about just regular life. She made spreadsheets to figure out the most cost-effective way to manage their TV, movie, and Wii consumption, the one thing that Ronald had been in charge of. She adopted a serious-faced little dog that the children doted on. She put up lace curtains that Ronald would have hated.

We took special care with their children, some of us having traveled the same road ourselves. We bought them small gifts and listened to their stories and sometimes said kind things about their father. They would grow up, as we had, and either forgive him or not, either make peace with the fact that he lived with a new set of children or not, either have a real relationship with him or not.

Ronald married The Elephant in a foreign ceremony, involving neither his nor The Elephant’s children. We speculated that they didn’t do a real wedding because his side of the aisle would be empty.

We don’t think of him often, but when we do, it’s as if he’s dead. We can’t quite believe he’s still out there somewhere, playing basketball with a different group of men, going out for dinner and making witty conversation with his new neighbors, insisting on dessert even though every one else is full. His birthday is just another weekend now, and we’ve forgotten if his short-cropped hair is curly or straight. On the rare occasions we spot him back here, it’s as if we’ve seen a ghost.