Faulkner called New Orleans “the city where imagination takes precedence over fact.”

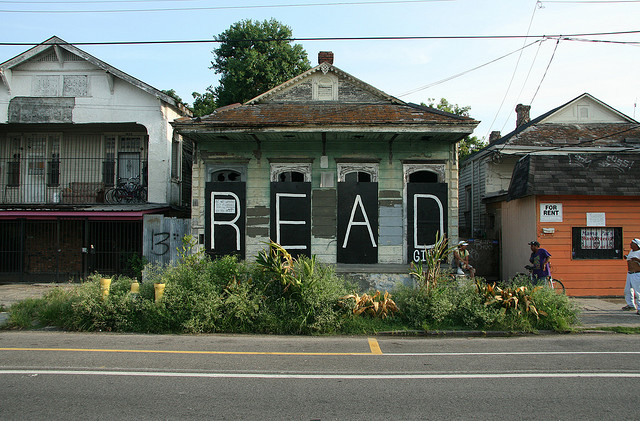

Fittingly, the miniature house on Pirate’s Alley where he lived during the 1920s is now a bookstore—and also a hub for much of the current New Orleans literary scene. Not far in any direction and you’ll find landmarks featured in some of America’s greatest literature, works like The Awakening, The Moviegoer, A Streetcar Named Desire, and A Confederacy of Dunces. With its opulent architectural charms, rich collision of cultures, and famously raucous celebrations, it isn’t any wonder why authors have long considered New Orleans a zone for inspiration. Even after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, the city continues to enchant not only its residents but readers and writers from around the country.

Gathering a panel of writers and scholars from the area, we asked them to talk a bit about the present, past, and future state of New Orleans literature.

Anne Gisleson’s writing about New Orleans and the Gulf Coast have appeared in various magazines and anthologies, like the Oxford American, the Believer, and Best American Non-Required Reading. She is the co-editor of How to Rebuild a City: Field Guide From a Work in Progress, a sort of citizen’s manual to post-disaster living.

Haven Kimmel is the author of several novels, including Iodine, The Used World, and The Solace of Leaving Early. Her book Something Rising (Light and Swift), about a pool hustler, is set in New Orleans.

Pia Z. Ehrhardt’s story collection Famous Fathers was published by MacAdam/Cage in 2007. Ehrhardt has also been published in Narrative magazine, McSweeney’s, and the Mississippi Review. She acted as guest editor for Guernica magazine in September 2009. She lives in New Orleans.

Duncan Murrell is a contributing editor at Harper’s Magazine and an instructor at the Center for Documentary Studies. He has written about New Orleans for Harper’s, the Normal School, and the Mobile Press-Register. Beginning shortly after Katrina, he lived and wrote in the Bywater neighborhood for eight months. He is @dvmurrell on Twitter.

Rosemary James and Joseph J. DeSalvo are the owners of Faulkner House Books and the founding directors of the Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society in New Orleans.

W. Kenneth Holditch is a literary scholar and professor emeritus at the University of New Orleans, and the author of numerous short stories, poems, and essays on major Southern writers. He is the author of Tennessee Williams and the South, and edited the Library of America’s two-volume edition of the works of Tennessee Williams with New York Times drama critic Mel Gussow. In his spare time, he gives literary tours of New Orleans.

New Orleans has one of the richest literary histories of any U.S. city, having housed such greats as Kate Chopin, William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, Lillian Hellman, Robert Penn Warren, Truman Capote, Walker Percy, and John Kennedy Toole. What’s one piece of literature set in New Orleans that you can’t live without?

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: All of the writers you mention have been important to me throughout my life, even before I moved here 30 years ago. Eudora Welty’s story, “No Place For You, My Love,” always knocks me down. Never more so than now because the couple drives south to Venice, “the end of the road,” for their tryst, a town slammed by Katrina and the oil spill.

Duncan Murrell: The Grandissimes (1880), by George Washington Cable. It’s fashionable to call this one of the most underrated novels in American literature, and I would tend to agree, but I also don’t care that much about what’s in or out of the canon. I just love the novel for the way it takes the romance of Creole life and turns it against itself, exposing its seaminess. This was an audacious thing for Cable to do, since he had largely created the image of the picturesque Creole in the minds of the nation at large with the publication of his book of stories, Old Creole Days (1879), and in the pages of Scribner’s Magazine before that. It’s a novel built out of his close observation of New Orleans society, and out of legend and myth. The old Creole warhorses, the unreconstructed, degenerate, and even murderous pomposities exemplified by Agricola Fusilier, are not spared; neither is the Creole system of plaçage, a part of a larger racial hypocrisy that could lead to the birth of the two brothers named Honoré Grandissimes, one white and one black, whose tragedy is the tragedy of the Creole way according to Cable. This novel is brilliant, finely observed, exciting, and ahead of its time. Mark Twain knew it, and he took Cable on speaking tour with him. There was a time when Cable was nearly the most famous novelist in America. Then he wrote some very pointed essays arguing for a radical racial equality, and was shunned by New Orleanians generally. His essays were entirely ineffective; he wrote them not long before Homer Plessy borded a streetcar on Press Street, launching a series of events that would lead to Plessy v. Ferguson and the codification in law of the regime of segregation. But I like that he tried to use his power for good.

Haven Kimmel: The obvious answer is A Confederacy of Dunces, and I do mean it—that book remains one of the most effervescent experiences of my life—but in truth it would be The Moviegoer. Nothing, nothing compares to it.

If New Orleans could be said to have a downside for writers, it would be that there is too much material all around, all the time.

Anne Gisleson: I’m with Pia on Welty’s “No Place For You, My Love.” The way it spirals out and reels you back in. But novel-wise, The Moviegoer, hands down. When I was younger—high school, college—I was resistant to it because there was so much Walker Percy in the house, on the shelves, and there was that uncomfortable sense of superficial recognition that made me disdainful, in an immature kind of way. But now, as an adult, I’m just grateful for almost every sentence.

W. Kenneth Holditch: A Streetcar Named Desire. It has put New Orleans on the literary map of the world more than any other work. It is one of the great American dramas by the greatest American playwright, a man who empathized completely with the outcasts in society—and he found plenty of those here. [But] I can’t deny that I consider The Moviegoer a great novel. My Literary Walking Tours of the French Quarter included always Pirate’s Alley, which Binx Bolling is passing through when he sees William Holden walking along Royal and decides that the movie actor must be on his way to Galatoire’s. Once I was leading a group of ladies from a book club and when we exited the alley onto Royal we were confronted with an amazing sight: Lillian Gish sitting in the high back seat of an old Packard automobile. I pointed out to my group that this was iconic—a fact that Binx Bolling would have considered significant—but alas, no one in my group knew who Lillian Gish was, so the point was lost.

New Orleans is known for being a great city for musicians and music lovers. The same goes for cooks and food lovers. What’s it like being a reader and writer in New Orleans?

Anne Gisleson: Fun, conflicting. You grow up with all of this interesting stuff around you that you don’t even recognize is interesting, and then by the time you do and you want to write about it, you realize that tons of people have already done so, some brilliantly and some lamely. And the writers keep coming and keep writing about your home, and it can be a little anxiety-producing if you let it get to you.

W. Kenneth Holditch: It’s like being a reader or writer in any other place except that here life keeps intruding on cerebral pursuits. There’s always a party to go to or music to hear or simply the siren call of the streets of the old Quarter. It can be difficult for writers for the same reasons, and they must be committed, imbued with the Puritan work ethic, to stick with it. However, the amount of inspiration the city provides is ample recompense for the difficult task.

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: For me, it’s engaging. This city’s incessant, demanding. It’s rare that I’m driving down a street passive, distracted, because the place is so alive, loaded with beauty and decay, noise, crime, grace, poverty, flowering shrubs, live oaks and crazy big banana plants, interesting people. New Orleans doesn’t let you take her for granted. Living here is like being in an up-and-down relationship.

Haven Kimmel: If New Orleans could be said to have a downside for writers, it would be that there is too much material all around, all the time. If I tried to transcribe half of the peculiar, vivid, outlandish, timeless experiences I’ve had there I would do nothing else.

Rosemary Jones: It’s easy to be distracted by the sights, sounds, and smells of New Orleans, which are seductive. At the same time the voluptuous nature of the city is energizing and inspiring.

Duncan Murrell: My experience of being a reader and writer in New Orleans lasted eight months. I used to ride my black cruiser bicycle to Faulkner House, where I browsed and ordered books, including the great work of New Orleans nonfiction, Rings by Randolph Bates. I used to write in Mimi’s in the Marigny and at the Sound Cafe, along with dozens of other writers, activists, street punks and layabouts. One of the bartenders at Schiro’s across the street from Mimi’s had a story in the first post-Katrina edition of the excellent lit mag, New Orleans Review (Vol. 31 no. 2), and I didn’t even know she was a writer. I would drive to Maple Street Bookstore, and one time I saw Chris Rose chainsmoking outside a CC’s Coffee up that way. It’s very easy to feel connected to other writers in New Orleans. New Orleans’s unique amalgam of cultures (French, Spanish, Caribbean, Southern) is a major component in much of its literature.

[Kate] Chopin was fascinated with Creole culture, Percy with the changing attitudes of the South, Toole with the city’s “Yat” dialect. As times change, is this unique cultural quality still a concern for contemporary New Orleans literature?

W. Kenneth Holditch: I would think so, although as the city becomes more and more “progressive” and “Yankeeized,” there is perhaps less material than there once was.

Anne Gisleson: That can be such dangerous ground to tread and the results are often painful. The “uniqueness” of the city has been a great boon and great enemy to writers down here for ages. The evocativeness of the surface—the architecture! the characters! the color!—can render such an easy payoff and is so seductive that it can distract from the real difficulties, complexities and thorny realities of the city. It’s one of the reasons Percy fled across the lake to Covington, a “nonplace,” to steer clear of the city’s particular influences.

I recoil from any novel or play or movie that has the obligatory scene at the Café du Monde.

Duncan Murrell: Too much can be made now, in 2010, of the French, Spanish and Caribbean influences. The French live on mostly in people’s last names, the Spanish in the architecture of the French Quarter. The Caribbean influence folds in both Spanish and French colonial influences, as well as aspects of the African diaspora. Of the three, the Caribbean influence is the most persistent. We should also note that the Irish and the Germans were major players in New Orleans culture. I think it’s somewhat misguided to try to pick out cultural influences by language and geography. It becomes hopelessly muddled the more you look into it. The most persistent cultural influence to me is the fact that New Orleans was a port city and a crossroads, a collector of people and things, the end of the river. And it’s still that way. It’s hard to overstate how much New Orleans loomed in the imaginations of 19th century frontier settlers, for instance. Once you got over the Appalachians and through the Cumberland Plateau and into the Mississippi drainage, one’s orientation to the world shifted from an east-west movement to a north-south one; or more specifically, an upriver-downriver one. And at the end of that river sat New Orleans. Nearly every outlaw legend that sprang up in the western territory in the early 19th century has some aspect that takes place in, or is related to, New Orleans. There is no legend of the Natchez Trace without New Orleans. The city is where crooks, race-traitors, Catholics, vagabonds, and every other marginalized person could go to hide and, sometimes, recreate themselves. To a great extent, it’s still that way. I see this culture of the crossroads in much of contemporary New Orleans (and south Louisiana) literature. You get it in Robert Olen Butler’s A Good Scent From a Strange Mountain, right alongside Poppy Z. Brite’s Liquor series of novels, Yusef Komunyakaa’s collections of poetry Magic City and I Apologize for the Eyes in My Head, James Lee Burke’s Robicheaux novels, Tom Piazza’s City of Refuge, and again, Randolph Bates’s great profile of the boxer Collis Phillips, Rings. (I’ve mentioned Bates’s book twice but I don’t know him or have any interest in selling the book, which is out of print.) I should also mention Nik Cohn’s very strange, recent book on New Orleans hip-hop, Triksta, which is also pretty terrific.

Anne Gisleson: One writer who captures certain voices that are unique to the city exceptionally well, not self-consciously or preciously is Patty Friedmann, author of Side Effects and A Little Bit Ruined. To go back to Percy again, he once wrote that ”the next Southern literary revival will be led by a Jewish mother, which is to say, a shrewd self-possessed woman with a sharp eye and a cunning retentive mind who sees the small triumphs and tragedies around her and has her own secret method of rendering it, with an art all her own.” And that is totally Patty Friedmann.

Rosemary James: The city’s rich ethnic diversity and its diverse dialects are still a tremendous concern. One only has to read Patty Friedmann’s Too Jewish to know that.

Residents of New Orleans are very protective of the ways in which their city is represented. When writing about New Orleans, have you ever gotten anything wrong? What kinds of stereotypes and misconceptions are easy to fall into?

W. Kenneth Holditch: The stereotypes are obvious: I recoil from any novel or play or movie that has the obligatory scene at the Café du Monde and has characters saying “chère” and eating jambalaya or gumbo all the time. Some people get it right, in literature and in movies: consider Treme, which, to my mind, gets it right almost all of the time and is therefore a masterpiece.

Rosemary James: The worst and most persistent stereotype about New Orleans is that it is an Acadian city and that everyone here speaks in Cajun slang. There is nothing whatsoever wrong about the Acadian culture and language of south Louisiana. What is wrong about the stereotype is that this Acadian culture is not the culture of New Orleans. Even such journals as the New York Times, which take pride in being being “journals of record,” translated as “journals of truth,” consistently get this wrong.

Joseph J. DeSalvo: People can’t keep the difference between Cajun and Creole straight, they also can’t get it through their heads that the vast majority of New Orleanians do not speak with a pronounced southern drawl, that, in fact, a huge percentage of New Orleanians sound like they come from the Bronx and that is because of the 19th and early 20th century ethnic migrations to New Orleans and New York were similar.

Haven Kimmel: I only focused on New Orleans in one book [Something Rising (Light and Swift)], and the only reason I’m fairly certain I got nothing wrong (and no one has ever said I did) is because I reported it exactly as I experienced it. Those characters and conversations were recorded in my journals very carefully, and over a number of years. Nothing I fictionalized happened all at once. I first lived in Biloxi, Miss., when it was still a strange and funky and kind of outlying place—that would have been 26 years ago—and then in New Orleans. My history there stretches across my entire adulthood. That is not to say that stereotypes and misconceptions aren’t the most dangerous and obvious pitfall for writers there—because of the extreme light and vivacity of the place—but they are everywhere else, too.

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: The city’s charms and clichés are hard to keep at bay. Before Katrina, I worked small, inside the houses, inside the characters. I’m interested in the unexpected, corner-of-the-frame details. The stuff tourists can’t get to without a local taking them in. People work hard and play hard here. It’s not all gumbo and parades, bohemia and funk. The books written after Katrina—Dave Eggers’s Zeitoun, Tom Piazza’s City of Refuge, Mary Robison’s One D.O.A., One on the Way—dealt with the aftermath more frontally. It’s going to be interesting to see how writers handle Katrina now, to see what role the storm plays in novels and stories, and if it’s anachronistic to set a book right after Katrina. I think many of us are made uncomfortable by the series Treme, how it’s rehashing and generalizing what we have moved beyond. How will we write about the quieter, less obvious pressures of living right now in a wounded, mending city?

Anne Gisleson: I think in writing about a place as complicated as New Orleans (or any city) you’ll always be getting things wrong. I’m sure I have. There are some things about the city that I once wrote with great certainty and no longer believe. Does that count? After the storm there were writers who were often referred to as the “voice of New Orleans.” I know what people meant by that or wanted to mean by that, but I still thought it was bullshit. The storm was a great unifier in a lot of ways, but there were still many voices, many, many perspectives. One of the most damaging stereotypes is the laissez-fare, lackadaisical local hanging out on the stoop all day drinking (coffee, beer, mint juleps, whatever), not caring about the future, just too caught up in enjoying the moment. There are so many hardworking people in this town, folks who have gone into overdrive over the last five years, but who are also unrepentant about enjoying themselves when they get the chance. Grocery checkout lines may move a little slower here than most places, but valuing conversation over expedience doesn’t mean we’re lazy. Just different priorities, I guess. The myth of some mystical nature of the city could be one of the worst because then it absolves you of the responsibility to investigate anything. Like I said before, it’s easy to get seduced by the enigmatic surface and go no further. We have suburbs, industry, boredom, like every other place in America. And now, somehow, a Superbowl-winning football team. As wonderful as the French Quarter is, it’s only about 14 blocks long, but it defines our national (and international) image. As locals we’ve often bought into our own myth and exoticism. We brand and sell ourselves that way, too.

Since Katrina, I’d say the number of AmeriCorps volunteers and ambitious millenials arriving in the city have outnumbered the “freaks.”

Duncan Murrell: I’m not sure how protective New Orleanians are of the way their city is represented. I think New Orleanians, with some exceptions, have been remarkably accepting of how outsiders portray the city, so long as they spell things right and pronounce Esplanade correctly. They certainly don’t mind outsiders swooping in and writing about the place; they even adopt them as their own sometimes. Faulkner lived in New Orleans only a few years, and while in residence wrote a decent if uneven first novel (Soldier’s Pay), and one terribly mediocre novel about New Orleans (Mosquitoes). Tennessee Williams was born in Mississippi, spent most of his childhood in St. Louis, and moved to New Orleans when he was 28. Kate Chopin, also from St. Louis, married a New Orleanian when she was 20 and they lived in the city for nine years before moving away. Robert Penn Warren, from Kentucky, lived in Baton Rouge for nine years. Truman Capote was born in New Orleans but spent most of his childhood in Alabama and New York. Lafcadio Hearn was Greek-Irish and grew up in Dublin. Sherwood Anderson grew up in Ohio, Walker Percy in Mississippi and Georgia, and on the list goes. All of them were outsiders of one sort or another. John Kennedy Toole was a native, and so was George Washington Cable. I run down this list not to impugn native New Orleanian literature, but to point out that New Orleans is a beacon for a certain kind of person, especially literary Southerners. It’s a freak capital, and thank God for it. The city is a shelter for a lot of creative people, and it couldn’t do it if its artistic culture were terribly insular and resistant to the outside. The opposite is the case.

That’s interesting to think of the city as a haven for outsiders, in that it seems to mirror New Orleans’s outsider status in American culture. But do you think a “freak capital” can be self-sufficient? Or will it always depend on the mainstream to be interested in it?

Anne Gisleson: I’m going to pick on Duncan on this one because I disagree with him on a couple of fronts. It’s one thing to use canonical examples of “outsiders” who represent New Orleans lit from the 19th and early 20th century (many of whom had deep connections to the city or spent years here exploring the culture) and somehow connect that to the contemporary, post-Katrina situation. Among writers and non-writers I know it’s been great sport over the past five years picking out the offensive, inaccurate and irresponsible things that even good and well-meaning writers have been claiming about the city, writers who “swoop in” for some great material, maybe hang out in some bars and coffee shops for the local color, maybe visit the struggling Lower Ninth Ward for some gravitas, swoop out to file and get a check. A lot of us are actually pretty sensitive to how we are portrayed because much of the support for the rebuilding depends on our national image, on an accurate portrayal of the city and its people. As I said before, it’s easy for some writers to pursue the low-hanging fruit of “freak” culture and eccentricity, ending up with a very narrow view of the situation here, [but it’s] a little more difficult to delve into the really complex issues of the rebuilding and the city in general. This is my home, my family’s home for generations, it was nearly wiped out and yes, I guess that has made me pretty raw and sensitive at times. But I don’t want to sound too cranky—because there have been really fine writers from here and abroad who’ve done thoughtful and important work regarding the city over the past few years.

The other night at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, the high school where I teach, we held a great reading by some newly transplanted poets, who all came here for different reasons, called New to New Orleans. In the discussion afterwards about the effect the move has had on their work, a few of them mentioned they were very tentative and deferential about using the city in their writing, feeling like they had to earn it because of the city’s deep culture and literary heritage/reputation. They were extremely thoughtful and weren’t taking anything for granted. And I agree that we value individuality, cultural connection and creative expression and that many outsiders are drawn here because of it—that sense of shelter Duncan referred to. But I take exception to the “freak capital” moniker. It’s another romanticization that I don’t think matches up to reality. And I live in the Bywater, which could be called the “freak capital” of a city pretty mainstream in its values. Take a real good look at this city, at the majority of its residents, of its neighborhoods, at who and what drives it. Since Katrina, I’d say the number of AmeriCorps volunteers and ambitious millenials arriving in the city have outnumbered the “freaks.” Which is OK, because they are generally better with a hammer or a grant proposal.

Prior to Katrina I had a great deal of optimism that soon the entire city would be gradually comin’ up and we would all live happily ever after. That…you know. Not so much.

Duncan Murrell: Culturally, a self-sufficent city is a discernible and distinguishable place, and most importantly, not dependent on outsiders for the perpetuation of that culture. By culture I’m not talking restrictively about art, but about the broader way people live generally. New Orleans is such a city; it has a large-enough native population with powerful attachments to the place, and these are the bearers of the culture. Yes, artists flit in and out, but the culture doesn’t depend on them to regenerate. New Orleans has figured out how to have its own culture, the fullness of it experienced out of sight of tourists, while also presenting a tasty and not terribly demanding version of that culture in a self-contained, sealed area of the French Quarter, with satellite outposts uptown and in the Garden District. Culturally, New Orleans is healthy. I exclude all bookstores from that characterization of the French Quarter. Bookstores are by definition subversive. I don’t have any idea whether all this can pay the bills into the future. And I’m sorry for calling you people freaks.

W. Kenneth Holditch: Actually I don’t understand the term “freak capital.” Is it meant to be derogatory or just “cutesy?”

William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams both lived for a time in the French Quarter, which was famously inexpensive in their day. A lot has changed. What other neighborhoods have since emerged as the city’s artistic centers?

Haven Kimmel: In New Orleans a neighborhood is either “comin’ up” or “goin’ down.” In my years there I’ve seen the Marigny go up, as well as the Bywater and Bayou St. John, and certainly the Art District and parts of downtown. Prior to Katrina I had a great deal of optimism that soon the entire city would be gradually comin’ up and we would all live happily ever after. That…you know. Not so much.

Anne Gisleson: I will be unequivocably partisan in saying the Bywater, two neighborhoods down from the French Quarter, where I live and work, is the most active new art scene—it’s totally exploded recently. We’ve been calling it Williamsburg South because we keep meeting kids from Brooklyn and we can’t keep up with the new writers and artists who’ve been moving into the neighborhood. New coffee shops, new galleries—we don’t know what’s going on, but it’s kind of exciting. And also scary, I mean, what do they want with us? Rents aren’t that cheap since Katrina. I imagine it’s the post-Katrina sense of purpose and romance, and also the tanked national economy?

Rosemary James: While the French Quarter remains a Mecca for many visiting, semi-permanent artists, today the Warehouse District, Faubourg Marigny, Bywater, and Tremé are just as important, primarily because the city’s leadership has for at least the last decade attempted to turn the French Quarter into a permanent stage for festivals, which are destroying the residential quality of life in the Vieux Carré. Tremé, always important in the cultural fabric of New Orleans, has been given a big national image boost by the new HBO series Treme, which has let people outside of the city in on the secret of this neighborhood adjacent to the Quarter on the north side of Rampart Street.

Joseph J. DeSalvo: For young artists, the Irish Channel neighborhood on either side of Magazine Street in New Orleans and Mid-City are still affordable. Both have wonderful neighborhood saloons and restaurants which are likewise affordable.

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: Barb Johnson (More of This World or Maybe Another) and Cheryl Wagner (Plenty Enough Suck to Go Around) live a few blocks from me. Is that enough for an emergence? Seriously, I’ve found that writers sort of keep to themselves here. And they’re scattered all over: the West Bank, Uptown, Downtown, Bywater, around St. Claude, in Holy Cross. This city’s extroverted but also private. I’m a transplanted Yankee and it took me 20 years to feel like a local, and even longer to find the writers. Although it took me about that long to admit I was a writer.

“The peculiar virtue of New Orleans, like St. Theresa, may be that of the Little Way, a talent for everyday life rather than the heroic deed.”

Duncan Murrell: The obvious choices are places like Marigny, Bywater, parts of Mid-City, the area around Spruce Street, and Maple Street Books in the Uptown/Audubon Park area. The lower French Quarter still has a scene, too, especially as a place for performances and readings. (See earlier mention of the reading series at The Gold Mine Saloon.) I think, though, if I wanted to write a great work of New Orleans literature, I’d live in the Irish Channel around the Norwegian Seamen’s Church. It’s got some of the louche vininess of the lower Garden District of Prytania Street, but there’s still plenty of places to live on the cheap. I’d rather live in a place like that, or in Mid-City, than in a place that is self-consciously and forcefully “arty,” like Marigny. Which is no longer cheap, anyway. Another area would be where I lived after Katrina, in Bywater right by the railroad tracks, two blocks from NOCCA. The New Orleans Center for Creative Arts is really unusual, being a high school that doesn’t wall itself off from the neighborhood. As a result, it’s had a positive effect, and the area around the school is hopping. It draws great artists, writers and musicians, they hang out in the restaurants and cafes, they show their work around the area, and are generally fun to have around. Thirdly, if I had to choose a place to live, I would kick Pia Ehrhardt out of her house with the great view of City Park and move my stuff in, pronto.

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: You’re gonna need a gun to get us out of this house. Better to bring cigars and we’ll spot you the gin and the porch.

In his 1968 Harper’s essay “New Orleans, Mon Amour,” Walker Percy said that “the luck of New Orleans is that its troubles usually have their saving graces.” What do you think he meant by that?

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: Grace, for me, is the key word in the quoted sentence, and, I think, in the essay. Grace in spite of long memories. I want to believe that proximity—blacks and whites living close to each other—is a second chance to treat each other with respect. There’s too much racial pain and viciousness to forgive—in our past and, sadly, ahead—but we can get along person to person, and know that our children, our worries and pleasures, and, also, this city, connects us. What Percy says here is closer to ground level: “The peculiar virtue of New Orleans, like St. Theresa, may be that of the Little Way, a talent for everyday life rather than the heroic deed.” I’m not sure that people in Philadelphia and Dallas don’t also have days filled with “Little Ways,” but I know firsthand that New Orleans does.

Haven Kimmel: Fate—and by that I mean daily events and obligations, either the delicate or the profane—has a way of containing manifold possibilities in New Orleans. And it almost doesn’t matter how they turn out, because the story one can tell about them is invariably fascinating and weird and captivating and like nothing else. It remains, for me, the richest city for a writer in the world. I miss it every day.

Anne Gisleson: I think he was referring to how the horrors of slavery eventually gave rise to the joys of jazz. It’s a difficult paradox that we live with but don’t acknowledge too much, that much of what we love about the city was built thanks to some hideous and sinful behavior. We are still struggling with it. The “luck” part, I think comes from New Orleans being a port city, a Southern, practically Caribbean port city, that embraces a culture of amalgamation and thus can produce some really cool stuff.

W. Kenneth Holditch: He says that in New York if one fell down in the street, the locals would step over him and grumble. In New Orleans, on the other hand, he said that there was still the chance, though it might be lessening, that locals would pick him up, take him to the nearest bar, and treat him to an Early Times. When I interviewed him late in the 1970s and asked if he still felt as positive about the “benign violence” of the city, he said he was not.

Rosemary James: The essay was originally written for a Dallas newspaper and I am pretty sure that what he meant was that New Orleans has been saved from becoming another Dallas, Houston, Atlanta megalopolis with no center, nor soul by the fact that the city’s leadership has traditionally been either incapable of putting together significant urban development or lacking the ambition to affect change for the sake of change. New Orleanians have an enviable indolence when it comes to change, knowing they have an enviable lifestyle and possessing a strong resistance to those hawking progress. I have seen New Orleans wear down some of the best, most ambitious developers in the country, putting so many stumbling blocks in the way of projects proposed by outsiders that the developers just throw up their hands in surrender and go away.

Percy writes—30 years ago, granted—from a perch that affords him the distance to be critical and pithy. Some of his observations make me squirm.

Joseph J. DeSalvo: New Orleans still has its architectural heritage while cities like Houston and Dallas have destroyed theirs in the name of modernization and progress. What those those cities have now is a complete lack of charming visual symbols of their history. They have only uninteresting concrete monuments to making money. As as a result of the lack of “progressive” leadership and the mañana attitudes in New Orleans, we still have something that people want to see and enjoy, such as our 90 separate and unique neighborhoods. It has been the strength of these neighborhoods and the resilience of their people that have fueled a remarkable recovery in the wake of the worst man-made disaster in American history, Hurricane Katrina. New Orleans endured a terrible ordeal as a result of Katrina. Most cities would not have been able to cope as New Orleanians have coped because they do not possess the backbone of strong neighborhoods, each with its unique cultural identity and each with a special pride of neighborhood that creates strong bonds between the residents. New Orleans suffered from Katrina but as a result of the storm-created building boom in the city, the crash of the national real estate market has been less devastating here than in the Dallas-Houston-Atlanta types of cities. And there are other saving graces from the Katrina troubles worth commenting on: Many young New Orleanians who left home to find better jobs before the storm have returned, bringing their talents to bear on the city’s future. They’re joined by young people from all over the country who see New Orleans as a sort of new frontier of exciting opportunities since Katrina. This is a roundabout way of saying that New Orleans has a history of being able to get up and come back alive quickly after blows that would have spelled death for many other towns. That is because New Orleanians have an enduring, strong strain of resilience in their DNA. And I think that this resilience is among the main attractions for outsiders, who stand back in awe of people who can lose everything, pick up and start all over again and sing in praise of the lord in the most beautiful voices on earth while they are at it.

Duncan Murrell: I’m going to throw something out there to spark an argument, as I know my feelings about this essay are not generally shared. It’s a beloved essay for a lot of people. Even so, I’ve come to think of that essay as an elaborate hoax, a put-on by Percy. It begins with the startling idea that New Orleans might offer “the way out of the hell which has overtaken the American city.” Well that’s interesting, the reader says, and utterly unexpected; let’s hear the argument. The argument consists of some perfunctory and unpersuasive examples of wishful thinking and outright fantasy, everywhere qualified by the exceptions. And the exceptions are long and detailed descriptions of a city that is anything but an example of fine city planning and thawing race relations. Percy’s recitation of these exceptions are by turns sad and hilarious, historically aware, and strange with juxtaposition, just like his fiction. I’d like to argue, absent a telekinetic link with the dead philosopher-novelist, that Percy knew he was damning the city with faint praise. I want to believe he meant to do this, and that the essay was a big joke. If it’s not a hoax, it’s a picturesque and near-total mess that undermines itself at every turn.

W. Kenneth Holditch: Certainly it is not a hoax. I talked often to Walker about the essay, and he stood by what he said, even as the city became more violent and he began to be less optimistic about its future in terms of racial harmony and other social matters.

After having prepared yourself by living and reading, write with your entire being. Be a good observer; be someone upon whom nothing is lost.

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: I don’t think it’s a hoax but the condescending tone rankles me. Maybe since Katrina, I’ve lost my perspective, my sense of humor. Percy writes—30 years ago, granted—from a perch that affords him the distance to be critical and pithy. Is his affection and concern for the everyday people of New Orleans genuine? Some of his observations make me squirm. He comes from a world more Comus than downtown, and Rexes get every bit as drunk as Zulu Kings. And do I feel guilty criticizing Walker Percy? Yes, I do. I just re-read The Moviegoer last month—for the first time since college—and the book’s truly heartbreaking and observant and generous. I thank God he wrote it.

Anne Gisleson: He was having fun with it, but a hoax implies a deliberate deception and I like to think Percy would’ve abhorred that. Despite the title, it’s not a love letter to the city. He was being thoughtful and honest in acknowledging the city’s great and deep flaws, its not-so-commensurate charms, and his hopes and fears for the city’s future, but expressing all of it with the same humor and nonchalance of polite, informed cocktail banter. It’s not a joke but rather a rhetorical choice. Percy was all about exploring the paradox that is the human condition and this essay is in line with that. Duncan, your description of the essay is exactly what Percy was trying to convey about the city: “it’s a picturesque and near-total mess that undermines itself at every turn.” A nearly 300-year-old mess we’re trying to dig ourselves out from now.

Duncan Murrell: Hoax is probably not the right word. But I do get the feeling he was having a little sport with the reader. Or, and this strikes me as being even more likely, Percy was constitutionally incapable of writing anything that didn’t simultaneously contain its own critique. The metaphysician often wins out in his fiction, why not in this little essay?

What advice would you give to New Orleans’s next generation of writers?

Pia Z. Ehrhardt: If you mean to the young writers coming up, I’d tell them to not waste a minute. To write with a full and worried heart and to proceed without fear. Don’t show your parents or your friends your work until it’s finished, or published, a done deal. If you mean writers navigating through the next 10 years of living in New Orleans, I’d tell them to get down low, work in close, crop the frame in unexpected ways, and let the characters tell their stories, not the city’s. Or maybe all of this is advice—even retroactively—that I’m giving to myself.

Anne Gisleson: Since I teach high school writers in New Orleans this is a question I guess I should have a ready answer for, but don’t. These students are in such a different position than any previous generation of New Orleanians, or Americans for that matter, in that they were all simultaneously forced from their homes and scattered across the country. Their worlds were blown open, and they saw different possibilities for living, some found themselves in better schools, safer neighborhoods, or places they thought intolerably boring compared to home or places they couldn’t wait to go back to once they had the opportunity. They brought that knowledge of differences back with them, and since New Orleans is such a notoriously insular town, where people can live whole lives within one neighborhood, this is pretty significant. Even so, Katrina has already become just another accepted part of their lives, their norm; they’ve grown up along with it. I think that’s where there’s a possible danger—the tendency to stop questioning and just accept things as the way they are. As a native, it took a long time for me to really see New Orleans, since it was part of me, and I’m still discovering and still learning about it. There is an incredible amount of historic rebuilding and reshaping of the city happening right now, and it’ll take years to sort through the outcomes. What was gained and what was lost. So, I guess I’d give the advice I’d give to any young writer, keep asking questions and paying attention.

W. Kenneth Holditch: Read. The major fault with much writing these days is that the writers have not studied monuments of unaging intellect. After having prepared yourself by living and reading, write with your entire being. Be a good observer; be someone upon whom nothing is lost.

Duncan Murrell: Don’t take the bus to Baton Rouge.