I.

A stack of weathered National Geographics sat inviolably on the bookshelves of my childhood home. I don’t think my parents ever subscribed, and, anyway, the set was strikingly incomplete: It included only issues featuring places that bordered Pakistan, the country of their birth, and its neighbors.

I remember clearly one with a photo of the Rajasthani boy tending his camel, and of course the beguiling image of the Afghan girl draped in a tattered burgundy shawl, her eyes hollowly aglow. We even kept an issue featuring Sita, a Bengal tiger, for its views of India’s jungles, women in saris squatting amid the shrubs. But I was most captivated by a cover showing a woman like a Mughal miniature brought to life, a cascade of pearls and gems hanging over her thick black hair to match the hues of her silken dress, seated amidst the sandstone columns of a palace court in Lahore. Tahira Syed sings elegiac melodies in a voice that shared the desperate and delicate dance of a butterfly caught in a jar. She is Pakistan’s most famous sitarist, but even before I heard her music, I saw her on the cover of that tattered magazine which had existed for longer than I had. I revered that single image of her the way most girls did Disney princesses.

It would be years before I discovered Syed’s voice, and many more before I could begin to understand what she was singing about. Somewhere in between, my brother began to play the tabla, a set of hand drums that sets the harmony for musical styles across South Asia. I joked with him about learning to play sitar so that we might travel the world as a brother-sister duo. It was sometime after that when I actually began to listen to the sitar and hear its range of emotions: the sounds as sultry as silk that slowly transitioned into lovers’ moans, the soft whimpering that turned into a frenzy of self-loathing. Some exposure to the sitar was natural enough, at least as the background of melodies that floated through backseat brawls on road trips, or bid sleeping passengers to wake up on flights to Pakistan. I can’t say that the instrument was the strange and seductive curiosity to me that it is to many other people. It’s music itself that has always been a little foreign to me―a language I could understand but never speak.

My parents didn’t root themselves in the suburban sensibilities that surrounded our cul-de-sac house; they never forced me to play piano or take up the violin, and by the time I left for college, I’d hardly touched an instrument that wasn’t handed to me for a public school Christmas program. Aside from leaving some old National Geographics lying around, my family didn’t make much of an effort to endow me with a reverence for the folk traditions of my people, either, and they never really indulged the collective fantasy offered by Bollywood films. I should say that they didn’t shun these things because of some very rigid interpretation of Islam―although my father did come to develop an almost religious hatred of headphones, claiming that the droning guitars and moaning voices my brother and I tuned in to would be forever trapped in our heads without the obvious escape route that his advice always seemed to follow.

The music I listened to was by and large a hymnal for Middle American angst. Still, it’s not that my own cultural topography was flattened into the tidy fields of corn I saw around me― I knew my ancestral terrain well enough, having spent nearly every other summer in Pakistan. I spoke fluent Urdu, even if it was pulled through the nose of a Midwestern drawl. I prayed dutifully whenever the azhaan drifted into the air from a little mosque-shaped clock that sat squarely on our mantel for years. I just hadn’t taken to exploring the sonic maps of my heritage until college, when the question of identity was first posed to me in a real way. It may have been since we were all around the same age that these other elements of our characters came to be more of a curiosity. Suddenly, “Where are you from?” and “Where are you from really?” were questions worth asking. Their answers carried conversations long into the night.

No such backstory was demanded of anyone in my small town of glowing grocery stores and 24-hour gas stations. Perhaps the people I played soccer with, went to movies with, crammed for tests with, swam in pools with, had no need to know about the country I hyphenated my identity with―although in some great way, they probably did understand, and not through my presentations of handmade rugs to my Girl Scout troop, or the samosas my dad fried up when my friends came by to watch bootlegged movies bought in Lahore’s bustling markets They knew I was different, knew not to ask why I wore tights to track practice on even the hottest days, knew never to ask me to dances, on dates.

Away from home, although just barely, I began to pore over Pakistani newspapers, though I had scoffed at my parents for watching satellite channels that brought them closer to their homeland.

This would all change in college, when boys from places that were my own hometown but with different names and in different states seemed to grow weary of what they had always known and suddenly found themselves slurring into my ear I’ve never been with a girl like you before. And with sober certainty, I knew just what they meant. For them, there was no doubt something seductive in this clash of cultures, a desire to conquer or to know intimately the other, but I could never shake the air of difference that hung between us. Still, I now wonder if it was through some desire of my own to engage the exotic that I took an interest in the sitar.

Everything I heard seemed to revere eclecticism. Green-eyed, brown-haired harpists in vintage dresses were mainstays in the music made for the entitled intellectuals and unabashed hipsters we couldn’t help but become. Boys in fedoras and tweed vests pounded out melodies on glockenspiels, children’s toys, both at once. But maybe eclectic is not so far from exotic. Maybe this was why I began to practice my scales in the hallway of my dorm, a massive brick haven for the artists and activists we defined ourselves as on our college applications. Now, away from home, although just barely, I began to pore over Pakistani newspapers, though I had scoffed at my parents for watching satellite channels that brought them closer to their homeland but farther and farther from the place they had made their home. Now, I got mad at my mother for having never taught me to wrap a sari, to read Urdu. I still refused to learn to make roti, though. I loved its steaming rounds but felt with some unplaceable certainty that by clapping that dough from hand to hand, I’d sound off a whole chorus of domestic obligations that I couldn’t bear to assume.

In the end, it seems that no identity is wholly administered. We pick the parts of ourselves we wish to carry around in our pockets and leave others tucked into drawers, hidden away, even from ourselves. Of course, our social selves are constantly renegotiated, and half of any culture is compromise. Knowing this, my mother had a makeshift kitchen set up in the garage to keep the pungency of her curries from settling into our sofas and pillows, from seeping right into the drywall. Still, I wonder what combination of ideas led me to so readily take up the sitar, and whether George Harrison or Ravi Shankar had more to do with it.

II.

The sitar has six strings to be plucked by a small wire pick worn on the index finger like a thimble, or by fingernails grown long to serve the same purpose. Another dozen or so thinner strands of metal run beneath. These sympathetic strings, as they’re called, form an underlying grid that offers the instrument its characteristic resonance. Like the chorus in a Greek tragedy, these strings provide a sort of integral accompaniment to the main chords, replicating their tones and forming an echo of the emotive melodies of an evening raag or a morning one.

So much of South Asian culture is based on just this sort of mimicry. An original idea is almost always balked at until some current of the masses embraces it, until it isn’t original at all anymore. When change does come, it is seen invariably as a growing pain, an awkward contortion of an escape artist pressing the bounds of the acceptable, the feasible, with no guarantee of success. It’s not that conformity is valued, but that failure in its exacting, individual nature is what is most feared. Scrutiny comes readily to admonish difference, but it is its own gesture of love, social pressure meant as saving grace―the only net that will catch those who veer off course.

I severed a centuries-old chain of events. Either you hum along to the age-old melody of obedience, or you strike discord.

Perhaps it is for this reason my mother took such offense at my refusal to wear the floral ensembles she bought for me, why she wove my hair into an unforgivingly tight braid even when I wanted it free. Worse than an ungrateful daughter, I was an unpredictable one. This was cause for consternation for someone who always had liked the things given to her, simply because she had liked those giving them. Because she was her mother’s daughter and I, somehow, was a stranger pulled from her own womb. Whether her dreams for me were polluted by the air of the industrial Midwest or my otherness came as a mutation caused by the genetically modified fruits of this soil, it was seen always as infectious, incurable. With revulsion, my mother would remind me, but you have your own mind, and that is what we get for coming here, the cruel gift of this country.

Slight and tawny, my body resembled hers, but it was the thoughts that Ammi could never trace. She blamed the stubbornness of adolescence when I disavowed the simple success of a career in medicine, but when I refused a suitor who was from a good family with a good job and good-enough looks, she began to fear that I had wandered too far astray to ever be roped back in—though she called me crying for nights on end, screaming into the phone, “Who is it that you think you are, anyway? Who is it that you think will be good enough?” In between these jabbing questions, she cursed herself for letting me venture off as much as she had, for leaving her own preserve.

Happiness is mapped onto the next of kin, displaced, as every generation tries to please the one before it. I denied my mother her right to plan for me the life she herself could not lead. I severed a centuries-old chain of events. Either you hum along to the age-old melody of obedience, or you strike discord.

III.

I only learned that there were sitar classes offered on campus from Sairah, a friend who was, of course, also Pakistani and incidentally, from my own hometown. She met me and Zaib, a new and mutual friend also of Pakistani origin, on the grass of the quad. Her cloth-wrapped sitar sat silent beside her.

“Where did you get that?” I asked, enchanted by the little ivory flowers and perfectly glazed mahogany Sairah revealed from beneath its graying cotton pouch. I don’t think any of us had actually seen one before that afternoon.

Sairah said she’d just bought it from a teacher and was planning on taking lessons off-campus twice a week. I found it impressive that she had discovered these classes, committed to them, while I was still getting lost en route to my political science lecture and regularly walking in to the cafeteria only to find it had just closed. To me, learning to play the sitar represented what I had always thought college to be: a quest toward arriving at some universal interdisciplinary enlightenment that could only come from amassing an array of mostly irrelevant skills and nearly ineffable ideas.

Zaib and I called the teacher the next day and signed ourselves up, but we soon came to find that neither of us was any good.

Overwhelmed by all there was to know and to do, we hardly made time to practice, and the little stickers scribbled with the monosyllabic notes—sa re ga ma pa—that our instructor had placed on our rented instruments never did come off. We joked about being in the remedial class. Kids no older than 10 moved ahead of us after a quick couple of lessons. The truth is that neither of us had ever played an instrument before, and our dorm rooms were so small we hardly had any room to keep our sitars, much less practice them. My roommate and I were constantly moving the thing around―from leaning against the mini-fridge, to perching on a reclining zebra-print chair, to lying on my lofted bed. All this shifting took its toll on my sitar: I cracked its base, only then learning that it was made from a dried gourd, and in fact quite fragile.

I tried to hide the crack from my instructor, a stern old man from a very serious school of classical Indian music that would have had no patience for my heedlessness. Needless to say, it didn’t take him very long to notice my Scotch-tape repair work. We would get no more than 15 minutes into our session when he would send us away with lectures about how our form was still all wrong, our scales still reprehensible. “There’s no way you can move on,” he would say, “until you master the basics,” and so Zaib and I remained stuck in a state of sitar purgatory.

I could barely even sit with the thing for those 15 minutes. You have to wrap your legs up around the sitar to play, and doing so would invariably make my feet go from completely numb to painfully prickly. One time, as I stood up, thanking our teacher for his reprimands, I fell right back down, nearly on top of him. That, and the damage I’d done to the rented instrument, basically sealed my decision to quit playing, but not before one very fateful incident in the elevator of my building.

I didn’t trust myself with the sitar on the narrow stairs after I had cracked it, so even though it was only two floors to the ground, I always took the elevator. One afternoon, I cradled the instrument with both hands and headed to my lesson when a tall, lanky boy I’d never before seen slipped in right as the elevator doors were about to close. Just after we passed the first floor, he asked me if I was carrying a bazooka.

“What?”

“Is that a bazooka? You know, the gun?”

“No, it’s not, and no, I don’t know. Why would I know?”

“Well, you seem to be from the part of the world where people like to tote those sorts of things around. Just try to remember, you’re in America now.”

The door opened before I could think of any sort of response to this, the other side of difference. He turned and grinned at me before stepping off, but I just stood there, fury rushing so fervently within me that I could hardly move. Later, I wished I had told him squarely that I was from a part of the world that retained an unhealthy obsession with weapons, a place where the vast majority of government money is spent on the military and other comparable sums go toward fueling conflicts around the world, including those in the place my family is from, but logic failed me in the face of such biting words, at that moment and in every other one like it.

IV.

The summer after I graduated from college, I got a scholarship to study Urdu in Lucknow, India. I had grown up hearing that anyone wanting to learn the language in its truest form should look no further than Lucknow. Once a gathering place for poets who competed for the praise of the court by improvising rhyming couplets, the city had long outgrown its indulgence of literary regalities. By the time I got there, hardly a trace remained of the graceful swoops of Urdu’s nastaliq script. Road signs and campaign posters were printed in side-by-side linear blocks of Hindi and English. Urdu and all of its majestic history had fallen from glory everywhere in its original domain except for the schoolhouse where I spent long, languishing days becoming literate in the language that had been my first to speak.

The decline of Urdu in India is a tale tangled in politics and trapped in ancient animosities, and the decline of North Indian classical music mirrors that of Urdu and of the rulers who adored it. Sybaritic and sensational, the nawabs—princely rulers—of Awadh, the territory that contained the capital city of Lucknow, prioritized artistic development over administering denizens. As early as 1764, Shuja-ud-Daula, then the nawab of Awadh, offered up a third of his fortune to British officials in exchange for a promise of protection against the looming threat of the Delhi Sultanate.

Ignoring increasingly fraught relations with the British, Shuja-ud-Daula’s son focused his attention on building increasingly imposing structures to serve as palaces, mosques, and the religious shrines known as imambaray―one fitted with an impossibly complex second-story labyrinth to flummox potential invaders. I tried to find my way out of this maze, once and then again a week later, but was unable to do so. Still, the thing that puzzled me most was how such an intelligently designed and intricately executed defense could offer protection from the brute force of mortar fire and cannonballs.

It was their patronage of the arts, and the arched doorways and endless corridors of their prized architecture, that mark these nawabs’ greatest feat, and also their greatest folly, for as the story tends to go, while their hallowed halls were filled with opulence, the people who lived in their shadows fell further into poverty. Unwilling to dirty noble hands by caring for commoners, the nawabs of Awadh relinquished more and more of their authority to the British, who eventually ran something like a mercenary government in the state. Charged with warding off invasion and collecting taxes, the British, of course, maintained always their own interests, allowing the nawabs to indulge their own―and they did.

The most notorious for lavishing in the arts was Wajid Ali Shah, who ascended to the region’s throne in 1847, when his family’s hold over Awadh had been all but lost to the British. Still, the young nawab reveled in the company of courtesans and musicians and dismissed ministers upon the advice of poets and eunuchs. Wajid Ali Shah would be exiled by the British from his ancestral land after a rebellion in 1857, but not before heralding a new school of classical music meant to keep up with the traditional Indian kathak dancers he so adored.

His voice took solemn tones as he admonished the British for looting his beloved Lucknow, the sore still infected more than a century after the injury.

Utilizing a wider range of notes than the “pure” Delhi tradition, the Lucknowi style of music had quick shifts that mirrored kathak dancers’ sharp movements. These innovations faced near-extinction after the British annexation of Awadh, during which the aristocratic nawabs dispersed for fear of the new regime’s wrath against their ways. Most people in the region despised Lucknowi music, which, in their minds, was connected to courtesans who they saw as no more than mere prostitutes. Were it not for a few enthusiasts who retrieved these disregarded compositions and introduced them to a generalized audience, the Lucknowi school of music would have been lost along with the rule of its patron family. Though the nawabs were once seen as selfish dandies, the 1857 rebellion and the increased power held by British officials in Awadh and across India made many nostalgic for the old regime, preferring the corruption of their own to the exploits of the other.

There are still some proud Lucknowis who lay claim to the city’s once-noble ruling family, including one mustachioed man who bared his breast to demonstrate his inherited bravado as he led me and a friend through the city’s royal gallery. He tucked it all away again when I asked why the gallery contained only poster-quality prints of those grand patrons’ portraits. Our tour guide spoke reverently of the nawabs’ construction of unparalleled palaces, their patronage of poetry. His voice took solemn tones as he admonished the British for looting his beloved Lucknow, the sore still infected more than a century after the injury.

I never asked and still don’t know who commissioned those portraits of Asaf-ud-Daula and Wajid Ali Shah, but to my surprise I would find the original oil paintings looking down on me from the walls of the British Library in London months later. I was working toward a master’s degree in South Asian studies at the time, and when I mentioned the paintings to a British classmate, he said at least they were preserved a world away from the dust and debris of India. All I could think of was the taxidermied heads of elephants and antelopes on lacquered plaques, trophies to the power of man over beast.

V.

Once, as I was leaving the British Library after a full day of leafing through yellowed correspondence and brittle-spined books, I saw a man amid the five o’clock hurry carrying something like an oversized squash beneath a tattered bit of cloth. He slung it over his shoulder with a woven cotton rope. Its size and shape, along with its makeshift packaging, made me sure it was a sitar. When I caught up with him, he said that it was actually the sitar’s smaller and easier-to-play cousin with just two stings, called a dotara.

We spoke for a few moments, amid a flurry of city striders. I must have stammered something about how I was interested in Indian classical music. (I was sick of stiff upper lips and frankly, desperate for friends.) He told me he was headed to a concert that would start in an hour or so. Since I had planned just to take the train back home, I saw no reason not to go, too. He wrote the venue’s address along with his name on a scrap of paper I’ve long since lost. He read out his name, an old Indian one, a couple of times but I still I couldn’t keep all the syllables straight when I tried to repeat it. I felt bad: I had wanted to say it perfectly, without disclosing any surprise that a rosy-cheeked Irishman with closely cut blond hair―it was almost a halo―would offer me some epic, clamoring Sanskriti phrase as his name.

Since I had time, I walked down the streets nearby, their quaint pubs and clean pavements bidding me on, as they might any American. I wondered how these streets must have seemed to South Asian students at the turn of the century. They were the subject of my research and their polite words in the face of a country that began to reveal itself as one unimaginably large contradiction whispered constantly in my ears.

Those students were, in many ways, just like me―inhabiting two worlds, brown skin in white collars. I was born in-between, but they were trained to be, as one British official put it, “intermediaries” in the social project of governing another man’s land. Arriving as students to the heart of empire to in hopes of joining colonial administration, many became, instead, revolutionaries. Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah―their faces became the very currency of independence for Pakistan and India, due, in part, to the ideals of a learned liberalism and a less-expected lesson in hypocrisy.

The ghosts of the old guards of Indian independence filled the alleys of Cambridge, too. As I struggled to find my own place as a student there, I wondered if Subhas Chandra Bose, a man who would take up arms against the British army in Japan, puzzled over which roll was his at a formal hall, and if Aurobindo Ghosh, the famed spiritualist, ever made it up to the roof of King’s College. The spirits of these men and so many others were with me in those arched corridors that must have reminded many of them, too, of Mughal palaces, but I felt those old boys draw especially near when I stumbled upon Gray’s Inn, the professional training ground for barristers, where so many relentlessly ambitious but inadvertently awkward South Asian students learned the legal codes they would later use to make a case for the independence of India—and Pakistan. And this is what England is for so many in the world, I thought, a pop-up book of our own past. A history I now lived.

Turning those pages, crossing those streets, later that evening I stepped into an empty storefront holding only some bikes, a couple crates of books. Two faces aglow in front of a computer monitor directed me without question down planked stairs. There sat the Irishman who had invited me to the concert, but he was no longer clad in the nondescript London uniform of well-tailored trousers and pale blue button-down. He was now swathed in saffron and crimson robes, sitting at the head of the room, cross-legged on a cushion, casually strumming his sort-of sitar. I awaited a conspiratorial smile, a sheepish grin, but got neither from Satyavachana or Ramchandra, né, no doubt, Christopher, Edward, or David. Instead, he greeted me just as he did the other few who stepped carefully down those stairs, with a chorus of low chants, readings from the Bhagavad Gita in translation, and a talk on forgiveness as the order of the world.

I thought immediately that I’d been deceived, but after some deliberation, I decided that hadn’t been conned, maybe only because the longer I sat on my dank carpet square, the more I felt calmed by all of it, dare I say, the essence of it. I realized quickly enough that this was a worship session and not a classical Indian concert, but wasn’t that the original point of that style of music anyway? And after so many quiet days breathing in 18th-century dust and taking notes on the transformation of young boys from the Punjab, fitted with their first tailcoats and taught to tie bowties, it was heartening to see the culture and faith they tried desperately to maintain still practiced on these streets they knew so well―and by the descendants of those who said they would freeze without meat during dreary English winters. And although I had fallen out of the routine of my own faith, I let myself absorb the rhythm of another, which said to seek the spiritual wherever you are, within whomever you meet.

I must admit that I had been reared to think of Hinduism as little more than blasphemy, and to my shame, I hadn’t thought all that much more about it, even as I toured temples and lived in the home of a Hindu family. But now, as my mouth opened to an om, I offered more than acquiescence. It was never asked for, but I sent along with that shared reverberation my acceptance. In India, at times, I feared being “found out” as a Muslim; yes, there are nearly as many Muslims in India as in Pakistan, but my understanding of the place was dictated by reports of sectarian violence and a very pronounced discrimination that kept me from opening my heart to appreciate Hinduism—in this or any other form, until I sat among a group of British Hare Krishnas in the former imperial hub of the world. The tales I had heard―the aversion I had been taught, I lost as the dotara hummed on.

I suppose this could be a karmic response to all of the bland Hare Krishna lentils I consumed in college without ever caring to learn what their barefooted street songs meant, what place the blue-skinned deity had assumed in the lives of so many suburban, middle-class moms and disaffected college kids. As the words of the Gita rose around me in a motley chorus of British accents, I realized that giving lasts far longer than looting, and in the endless mathematics of time, there is space enough for sharing.

VI.

Many people I met in England told me of their time in India―spent no doubt, in Thai fisherman pants and T-shirts, clutching always a full liter of mineral water like so many of the Brits I ran into in temple cities or on mountain outposts. I wanted to write off their interest in India as a nostalgia for empire, a long-lost longing to know what had once belonged so squarely to their forebears, the same sort of intrigue that draws one up the attic stairs of an ancestral home. But this meant I had to reconcile my own interest in India, since while much in the way of culture is shared, my own fascination with the country next door may well amount to a similar separation anxiety from a subcontinent sewn together in the mismatched prints of a pre-colonial quilt very nearly dyed the same hue before being torn in two.

This was something I wanted to make clear to people in England―I had no connection of my own to India, not by blood nor by land. My family, as far as I know, has always lived squarely within the boundaries of what is now Pakistan. My ties to the India came first through history books, and then through collections of short stories about subcontinental severance that I read in a language that had been all but pushed out of India. In the early 1930s, as the protests led by Ghandi against British rule gained force, fault lines began to emerge between faiths, and political leaders postured around these societal ruptures. The result was two countries born from the end of a single empire. Sectarian violence swept all corners of the region, forcing Hindus to flee to India and Muslims to seek refuge in Pakistan.

They took only what they could carry: family gold tied up in the seam of a sari, bundles of money tucked uncomfortably into a loafer. There was no place for anything that weighed more than one’s life.

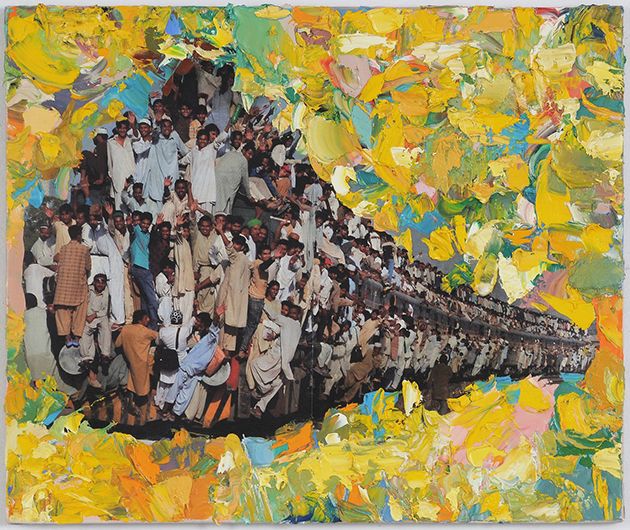

Millions of Muslims walked like herded animals to a country whose name meant “land of the pure,” crossing paths with Hindus and Sikhs just like them. Their bodies were alike, yes, but their spirits? Either way, they were skin and bones, many of them, when they collapsed in a land that embraced some―and expelled others.

The border wasn’t even demarcated fully when murderous rumors turned to brutal killings. Men carved their names into the flesh of Muslim women after raping them; a Sikh man shot his daughter, sister and niece to “save” them from being abducted and abused; whole trains of Hindus arrived at the end of the line with only corpses for passengers. There seemed no mercy left for those who sought God’s graces in contrasting ways, so millions were left to march. Living rivers of thirsty salvation seekers, bound for India or Pakistan. They took only what they could carry: family gold tied up in the seam of a sari, bundles of money tucked uncomfortably into a loafer. There was no place for anything that weighed more than one’s life. For brand-new radios or cases of books, for handmade rugs.

I can’t imagine leaving behind a home, a chicken coop, a set of fine silverware, the golden-sequined excess of a wedding dress, family photos, antique furniture with ivory inlay―to carry instead only a key on a pant string along with a prayer for a peaceful return to the four walls in which one’s father spoke his final words, sputtering the last of them into a brass spittoon. So many marched east and west holding on to keys as proof that they would not live as nomads, that they would again settle―but where, but how? In a land promised by politicians, pulled apart from what had been consecrated for a European queen. Still, it had been theirs all along―not as a country, but in corners, along alleys, in open fields they had belonged.

I have never lost anything, really. An odd earring, fine, a cellphone, at least one glove every winter, and once, somehow, a single sandal on a beach. The only thing that I have ever lost and then longed for was my sitar.

I bought it, my own glorious instrument, in India. Handmade, of course, with a rich sandalwood finish and little bits of mother-of-pearl embedded along its neck. I picked it out with a friend from my language program and our sitar instructor, our ustaad. Once a week, we toted our matching sitars to his home to take our lessons on the same mat on which he slept and ate. That all-purpose bit of foam was where he taught us our scales. Where we sucked our fingers after repeating over and over again the only song we learned, one from an old Bollywood movie about a girl kidnapped from the carefree youth of a tree swing and raised in a brothel where she sings coyly, “What’s a heart? Go ahead and take my life.” We performed this song, imperfectly but joyously, at an end-of-term event. We would be leaving for America the next day. My sitar would not make the journey.

I had gained much in India, a wealth of insight that stretched a learned national identity to a regional one, an understanding of a literary tradition I’d never known before, good friends and memories, but as any such trip does, this one came down to two plump suitcases and no money to my name. Worse, I’d spent all I could of my parents’ generosity. Without the funds to pay for excess baggage fees, I took my sitar to the post office to mail it back to Ohio―and prayed it wouldn’t cost more than the few thousand rupees I had in my wallet.

Instead, I was told that the sitar in its custom case would not be allowed―it had to be shipped in a separate box with a more standard shape. So the search began. My ustaad rode with me on cycle-rickshaws searching for someone to build one. Construction workers sent us to cabinet-makers who referred us to a man at the edge of town who built coffins for Christians. We found him, but not before nightfall. I pleaded with him to put the box together then and there, just a few nails, some thin board, but he refused. My teacher promised he would mail my sitar to me in England, since it was only half the cost of mailing it to America. I promised to wire him money.

I got back and dialed his number after the string of digits on a calling card. The post office had originally estimated about $150 for shipping. But now he said it would cost $600, which was nearly twice as much as the value of the sitar, its custom case, and the coffin put together.

I didn’t want to think he was cheating me, but I could see why he might. I was a kid who made an investment to indulge a hobby I hadn’t yet taken up. Who he knew carried back whole suitcases stuffed with so much else: saris, embroidered tops, silver jewelry set with stones a fortune-teller told me to wear. And I was from America, after all, which no doubt implied wealth to him and so many others in India, if only because of the exponential allowance of its exchange rate. Maybe I could have sent the money along knowing the sitar’s value would be so much more in the States, inflated by all the miles it would have to travel to get back to me. I could have obliged just to help a teacher who took time to show us the best of his city, who treated his students like friends. But in the end, I couldn’t justify the cost.

I wanted it. I did. I wanted to keep playing, to find my college sitar teacher again and tell him I would practice this time, that I had finally learned how to sit with my legs folded up under me, finally, that I was building up callouses enough to force the sound. I tried calling my Indian ustaad back once to tell him to send it just to Lahore where my dad’s sister lives, but I couldn’t get through. I could have tried harder, called the program and told them to put me in touch with that long-haired and lonely musician, but instead, I resigned myself to the sitar’s loss.

Many, no doubt, did the same in 1947. I have no way of knowing how many sitars were brought across the border during partition. Surely, for some, the instrument was a livelihood, carried through deserts and across plains, always under a splintering sun. Then, as now, I’m sure sitars were made in Pakistan, too. In Lahore, certainly, I could buy a new one. But classical music ails in that “pure” land. Unlike in Hinduism, where art can be worship all its own, many Muslims see it as nothing more than a distraction from one’s faith, a contest to the creative powers of a solitary God―or worse, a beckoning call to the devil. Simple percussion and maybe a harmonium are all that accompany the repetitive, devotional songs that taken to the fore of Pakistan’s folk music. The evocative twangs of the sitar are largely relegated to red-light districts, where women like the courtesan Umrao Jaan must still ask, “What is a heart?”

Something that can be bought and carried? Something that can be left behind.