The Big Apple's Nametag

Though it was dark for over 30 years, the neon sign above the New Yorker Hotel, for many of its former residents, never truly dimmed. Attending the hotel's anniversary celebration, the night the lights switched back on in Midtown.

Joe Kinney wore a camera around his neck like an old-fashioned reporter. It was a cold night in early December, and he was working the ballroom at the New Yorker Hotel, his flash firing off at regular intervals like the accent cymbals of the canned big band music that filled the hall. This evening the hotel was celebrating its 75th anniversary and Kinney, chief engineer, one-time resident, and unofficial historian of the New Yorker, was in good spirits.

“Who’s been kissing you?” his wife asked as she wiped lipstick off her 55-year-old husband’s boyish face. Kinney stretched his grin into an exaggerated grimace meant to imply quick-thinking.

Kinney first met his wife in the very same ballroom 20-some years earlier, when the New Yorker served as headquarters for the Unification Church. They were married across the street—along with 4,150 other apostles of the Reverend Moon—in Madison Square Garden; then, as newlyweds, they lived in room 2559. When the Kinneys, along with many of the other young church members, traded their quasi-communal lifestyle at the New Yorker for mortgages in New Jersey, the church decided to return the historic building to its original purpose. Closed to the public since 1972, a victim of the city’s fiscal crisis, the New Yorker Hotel reopened in 1994, with 178 of the original 2,500 rooms available for guests. By 2005, more than 800 guest rooms were open, as were several floors of student housing, commercial tenants, and a television broadcast studio. Kinney helped oversee the renovation.

“It’s like you’re asked to restore a classic car—your 1957 Chevrolet or your ’38 Duesenberg,” he said.

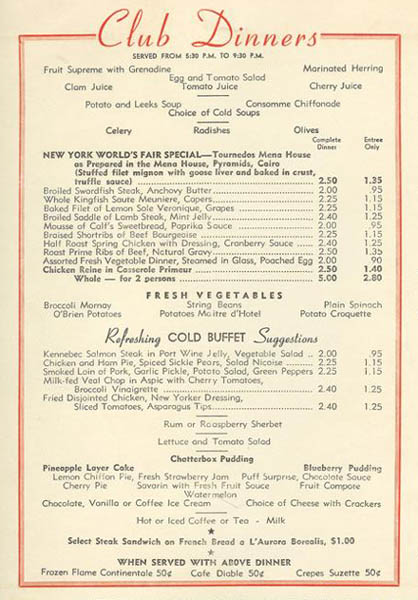

In fact, the New Yorker is a Depression-era Deco Supreme, and, when it was built in 1930, the biggest hotel in the world. The power plant in its basement was the largest private plant in the country, powering the 42-story building and its 10 private salons, five restaurants, 42-chair barber shop, and 92-operator switchboard. Its world-famous Terrace Room, where Benny Goodman played nightly from 7 p.m. until 2 a.m., had a retractable ice rink for luncheon stage shows, and for two bucks you could get a deluxe dinner of sweetbreads mousse or a whole sautéed kingfish. Early advertisements promoted the hotel’s Protecto-Ray Bathrooms (“They’re sealed with cellophane!”); central air and heating (“made-to-order weather!”); and the truly unique amenities of something called Novolescence (“a word coined to describe our $2,000 improvement program!”) which may or may not have been, simply, in-room television.

During World War II, thousands of soldiers on leave stayed at the New Yorker, which is connected to Penn Station by an underground tunnel—now filled with box-springs and drywall. Wartime ads quoted celebrity patrons in a reminder to all hotel guests that it was their patriotic duty to make reservations well in advance: “We’ve overlooked this battle,” said J. Edgar Hoover of the hotelier’s efforts. “America is on the double-quick,” was the admonition from Will Rogers Jr.

The New Yorker held onto its reputation as a swank affair after the war. Even punks like Holden Caulfield made a point of inquiring about who was playing at the New Yorker. But as the big-band era drew to a close, so, too, did the New Yorker’s heyday.

Some of the attendees at the anniversary gala scrutinized the memorabilia arranged by Kinney in display cases near the bar or were engrossed in the slide show that highlighted the hotel’s most famous guests (Muhammad Ali just after he lost his 1971 “Fight of the Century” against Joe Frazier, Joe DiMaggio during the 1941 World Series, inventor Nikola Tesla during the last years of his life). Most there got their retro-fix from the music alone—a steady stream of Sinatra, Garland, and Glenn Miller. “My mother said you wouldn’t even walk down Fifth Avenue in those days without white gloves on,” commented a representative from the hotel’s lead bank. “And every man wore a hat,” her colleague agreed between bites of shrimp cocktail and potato au gratin.

After dismissing the urban legend that labels the sign as the cause of the blackout in 1965, Smith conceded, “We’re really, really crossing our fingers tonight.”

At one table, a divinely silver-coiffed lady in a feathered black dress and pearls sat tapping her foot to the music. She was Jeanne Cummins, and she had flown in from Columbus, Ohio, to attend the party, despite a fall that had necessitated more than 50 surgeries. “I have an artificial knee, an artificial hip, and a rod and 30 plates in my leg. You should have seen me going through the metal detectors,” she laughed.

Ms. Cummins was born Ethel Mae Thompson five years after the New Yorker Hotel opened. By the time she was 15, she was singing in nightclubs in central Ohio. That’s where the hotel’s bandleader, Bernie Cummins, on tour with his orchestra The New Yorkers, found her and signed her up. “I wasn’t allowed to date anyone in the band, so I married the bandleader’s brother,” she explained.

At six o’clock the general manager of the hotel asked the guests to turn their attention to the monitor at the front of the room. It showed the view of the top of the hotel’s ziggurat-like tower, as seen from Ninth Avenue. The 21-foot letters spelling out “The New Yorker” were barely visible in the dark. The sign, which figures prominently (and in simulated neon) in the opening of the David Letterman show, has in fact been dark since sometime around 1967. After dismissing the urban legend that labels the sign as the cause of the blackout in 1965, Smith conceded, “We’re really, really crossing our fingers tonight.” Then he called Jeanne Cummins up to flip the switch. The assembled crowd counted down from 10 and then, as the sign lit up and went into a blinking letter-by-letter mode, like a string of strobe Christmas lights, everyone cheered. In the crowd, Joe Kinney wiped a hand across his brow and made a face of mock relief.

Ms. Cummins took her seat and listened to details for the $40 million renovation scheduled to begin in March, which will replace the current neo-classical lobby and non-descript room interiors with stylistic Deco details linked to the hotel’s heyday. “The pendulum swings,” she said, “and they say it swings back the other way. But I don’t know.”

After the party, Joe Kinney headed home with his wife. As he looked eastward over the Hudson from Linwood, he said, the New Yorker was the brightest thing on the horizon. Brighter even, he mused, than the spire of the Empire State Building. For a minute he wondered if the New Yorker was leaching the light from the rest of Midtown… if there was some truth behind the urban legend of the blackout of ’65.