The Combination Lock Test

A man dies, leaving behind, among other things, a combination lock. Opening it may just prove the existence of the afterlife.

A few weeks before my 30th birthday, my wife and I drove to the local hardware store to buy a combination lock. Inside, a man in an employee’s red vest, easily twice my age, approached us. “Help you find something?” he asked.

I thought I might answer him. A lock. No factory combinations. Something I can set myself. Then I thought better of it, for some small fear that the man might ask what I needed it for. I might have lied. A gym locker, a jewelry box, a gun cabinet.

“Nope, we’re fine, thanks.”

The store sold dozens of combination locks. “Hey, this one has a pink dial,” I told my wife. I checked the packaging. “But I can’t set the combination myself.” We looked for a few minutes more before she spotted a wide Master Lock. “Look at this one,” she said. The lock had five green dials covered with letters and numbers. The packaging claimed the lock offered more than 25 million possible options for opening its clasp, and offered an understated reminder: “Be sure to record your secret combination.” We bought the lock, brought it home, and I set my combination. I repeated the combination a few times to myself, then I placed it on my desk where, I expect, it just might stay until I die. And when I do, what will become of it then?

I was raised with a Catholic’s notion of life and death, the idea that a person’s mortal life determined how he’d spend eternity. By the time I was eight years old, however, I had started to pester my parents with existential questions. “Where do we go when we die?” I asked my mother one sleepless night. “Heaven,” she replied. Her answer briefly soothed me, and she returned to bed. A few moments later, I returned to my parents’ door. “But how do we know it exists?” My mother had my father respond to my questions for the rest of the night.

I struggled to find some concept—some key, some combination—that might help me make peace with my fear of death. Instead, I found Ian Stevenson.

Religion never settled my anxieties about death. Some nights, my heart raced while my mind looked for some idea that might calm my nerves. I struggled to find some concept—some key, some combination—that might help me make peace with my fear of death. Instead, I found Ian Stevenson.

I first learned about Stevenson through his obituary, which ran in the New York Times in 2007. My wife and I have a habit of sharing interesting obituaries with each other. I sent Stevenson’s to her, with a few sentences highlighted: “Tucked away in a file cabinet in the Division of Perceptual Studies is an ordinary combination lock, which Dr. Stevenson bought and locked nearly 40 years ago. He had set the combination himself.” A colleague told the Times that Stevenson hoped to communicate the combination to a friend or loved one, who could open the lock and prove that some part of Stevenson had survived death.

Ian Stevenson, who was born in 1918, spent about half his life studying reincarnation and past-life memories. He documented thousands of stories from young men and women who claimed to recall previous lives, whose birthmarks resembled fatal wounds sustained by others. Perhaps Stevenson’s death provided him with the answer he sought for most of his life. For me, it simply rekindled the question I’d struggled with for most of mine: What happens when we die?

As a child, Ian Stevenson suffered from frequent bouts of bronchitis. In an essay in Harper’s, he described the chronic cough that slowed his childhood—cool summer afternoons in Ottawa during the Great Depression and the redevelopment of the city center, spent indoors while his friends played football, his bronchial tubes flooded. “This went on for years … until gradually I became aware that respiratory function was not improved by sitting on my spine and hypoventilating,” wrote Stevenson. The recurring illness also prompted his first considerations of life and death. “As eternity approaches, temporality becomes more precious,” he wrote, “because it has been much wasted.”

Stevenson studied biochemistry and psychiatry then completed his residencies—first in Montreal, then in Arizona when an acquaintance suggested warm air might be easier on his strained lungs. He accepted a biochemistry fellowship in New York, studied psychoanalysis in Washington, and met Aldous Huxley and took LSD somewhere along the way. By 1957, he was in Charlottesville, Va., as chairman of the University of Virginia’s psychiatry department.

Stevenson’s childhood interests in eternity and temporality had tangled inextricably by the start of the next decade. He confessed in an interview that he “wasn’t satisfied with psychoanalysis or behaviorism or, for that matter, neuroscience,” and added, “Something seemed to be missing.”

He began to travel to Sri Lanka and India, where he interviewed children who recalled their past lives. In 1966, he published Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation, which included many of the stories he gathered during his travels, along with his investigations of their tales. “In the international census of cases suggestive of reincarnation which I have undertaken, I now have nearly six hundred cases listed,” he wrote in Twenty Cases.

Perhaps, after the death of its keeper, a combination might be communicated, its lock unclasped, its mouth opened.

The next year, Stevenson launched a new office within the University of Virginia’s Department of Psychiatry called the Division of Perceptual Studies. Much of the division’s early work focused on Stevenson’s interest in reincarnation and past-life memories; during the division’s first five years, Stevenson and his colleagues traveled more than 300,000 miles and interviewed more than 1,000 men and women who recalled past lives. As Stevenson’s research attracted other scholars and increased funding, the division looked beyond reincarnation. Staff members also gathered accounts of extra-sensory perception, apparitions, and out-of-body experiences. Stevenson, however, remained focused on stories of past lives and reincarnation.

One such story came from Dolores Jay, who lived in Mount Orab, Ohio, with her husband, the Reverend Carroll Jay. In 1970, Rev. Jay attempted to hypnotize his wife in order to help her cope with back pain. As he spoke to his wife and stroked his fingertips along her forehead in a steady circular motion, she addressed him in German and claimed her name was Gretchen Gottlieb.

Dolores Jay grew up in Harrison County, W.Va., where her parents still lived. Stevenson interviewed them, along with her sister and neighbors, to confirm Rev. Jay’s claims and his wife’s background. None of her family members spoke German, nor did the Harrison County schools teach the language at the time.

The story of Gretchen Gottlieb attracted Stevenson to Ohio, where he met the couple. He invited Dolores Jay to Virginia, where he recorded numerous conversations with “Gretchen.” A reporter from United Press International who was fluent in German joined Stevenson for one interview. Stevenson posed his questions in English and Jay replied in German as Gretchen. Their conversation ran in the Chicago Tribune:

“How old are you?”

“Vierzehn,” replied Jay. Fourteen. She was actually 52.

“Where do you live now?”

“Eberswalde, ja.”

“Where is that?”

“Deutschland.”

There were other names—Laureen Tuttle, from Springfield, Ind., dead at 24 from a “blood disease”—but Stevenson spent most of his time with Gretchen Gottlieb. In nearly 20 sessions with Jay conducted in Virginia in 1974, Stevenson counted more than 200 German words and phrases—more, he argued, than a person could passively absorb.

Another story, collected by one of Stevenson’s colleagues, involved a 36-year-old Sri Lankan incense salesman named Jinadasa. In April 1985, a bus struck Jinadasa while he rode his bicycle to a market near Kelaniya. The accident fractured the ribs on the left side of his body, and Jinadasa died from his injuries.

Two years later, a girl named Purnima was born in the city of Bakamuna, more than 100 miles from the site of Jinadasa’s fatal accident. As a child, she recalled landmarks near Jinadasa’s home, and the names of the incense he sold. She also had birthmarks along her left ribs, in the same spots where Jinadasa’s ribs had cracked. In Life Before Life, another of Stevenson’s colleagues, Jim Tucker, writes that the evidence gathered by researchers for Purnima’s case “challenges attempts to write off this work with a quick, normal explanation.”

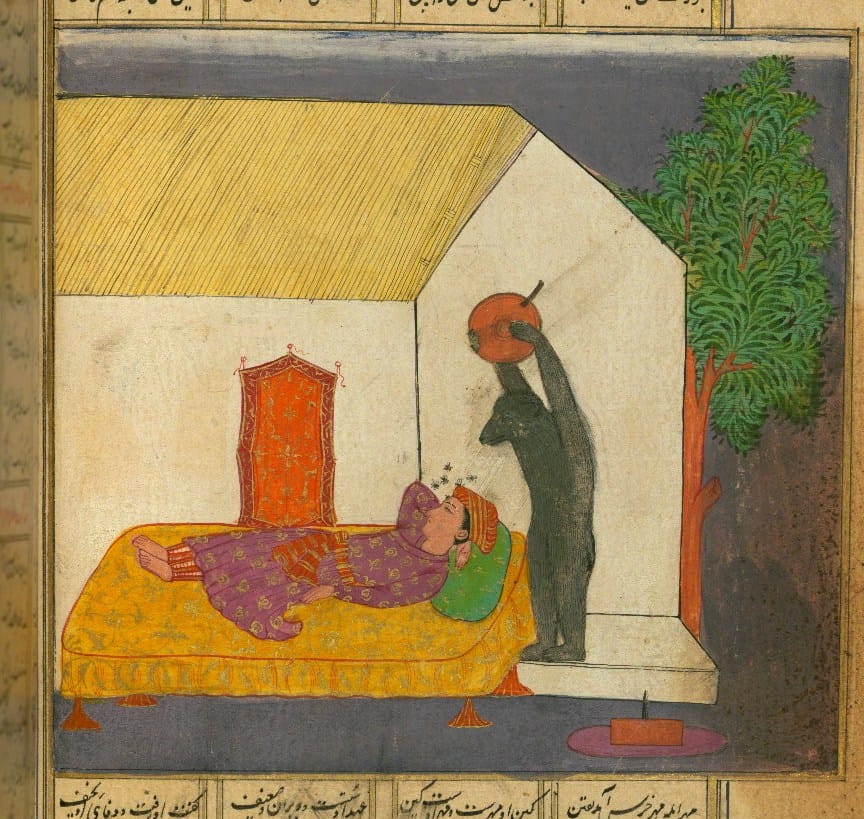

The Combination Lock Test for Survival began the same year Stevenson founded the Division of Perceptual Studies. Stevenson had heard a number of stories from colleagues about men and women opening combination locks set by deceased loved ones. In one instance, a widow opened a locked box, though she claimed her husband was the only person who knew the combination. In another, a widower asked a medium to help him open a lock set by his deceased wife, and the medium recounted the correct combination. Perhaps, after the death of its keeper, a combination might be communicated, its lock unclasped, its mouth opened.

Stevenson purchased a Sargent & Greenleaf model combination lock from Brown’s Lock & Safe, a Charlottesville locksmith located a few miles from his home. He set its password then placed the lock in a drawer inside his office.

“In setting my own locks, I started not with meaningless random numbers, but with a word or phrase that is extremely meaningful to me,” Stevenson said at the time. “I have no fear whatever of forgetting it on this side of the grave and, if I remember anything on the other side, I shall surely remember it.” Though, on one occasion, Stevenson opened his own lock—in 1975, to check either the lock’s reliability or his own—then closed it again.

The Division of Perceptual Studies collected 10 more locks—a duplicate for Stevenson, and nine others. Upon news of the death of a lock’s owner, Stevenson awaited contact from family or friends who might have received some suggestion of a combination, or might have visited a medium for help contacting the dead. When a colleague and fellow combination lock owner died in 1979, Stevenson received more than 40 letters that suggested combinations, and consulted two mediums himself, his colleague’s lock in his pocket. All combinations failed.

By the turn of the 21st century, Stevenson and his colleagues had investigated “more than 3,000 cases of possible reincarnation,” according to the New York Times. In 2006, Stevenson published a short survey of his work with past-life stories. “Let no one think that I know the answer,” concluded Stevenson. “I am still seeking.”

The same could be said for his combination lock tests. “Despite the disappointing results we have had to report,” Stevenson wrote, “these tests are not necessarily concluded.”

Stevenson died of pneumonia on Feb. 8, 2007. His physical world had been reduced to the community of his nursing home. His wheelchair-bound wife lived in a neighboring room, and his 90-year-old brother down the hall. Both were in Stevenson’s room when his heart stopped. A friend, visiting from Iceland, was also by Stevenson’s bedside. “We all waited, perhaps as if he might come back,” he wrote later. “We all sat or stood silent. He did not come back.” Stevenson’s lock remained in a filing cabinet in his office, closed for more than three decades, while the combination—along with thousands of reincarnation stories, and the last awareness of his family gathered around him—left his body, to go wherever all such things go.

I lived in Charlottesville, in a drafty two-story house on Ninth Street, when Stevenson died. The house had stucco walls, painted a pale yellow, and one of the two second-floor windows had been roughly plastered over. With the remaining window illuminated, the facade seemed to wink at the street.

The house had been built in 1925, a year that Stevenson, most likely, spent confined to his bed, his breathing strained, coughs racking his body. The house was a mile from the local newspaper, where I worked as a reporter. My morning walk took me past Brown’s Lock & Safe, where Stevenson had bought his combination lock, and where I had my keys cut.

My landlord, an architect, was the grandson of one of Stevenson’s colleagues, another participant in the Combination Lock Test. For a year, I paid him reduced rent to live alone in the 1,400-square-foot house, in exchange for yard work that we never quite got around to. On one occasion, I asked him about his grandfather’s work, but my landlord remembered very little about the man, and said his grandfather had not communicated anything to him after his death. “But,” my landlord added, “I’ve always tried to be open to that sort of thing.”

A few years after Stevenson’s death, a man named Mark invited me to spend two weeks with his paranormal research group, Spirit Search Paranormal Investigators.

A few years after Stevenson’s death, a man named Mark invited me to spend two weeks with his paranormal research group, Spirit Search Paranormal Investigators. The group had recently filmed a television segment for A&E’s My Ghost Story at the Gordonsville Exchange Hotel, a former Civil War hospital near Charlottesville. Mark asked me to join him for a return trip to the hotel, where he’d recorded hundreds of audio files that, he suggested, contained inexplicable sounds. I told him I’d bring my own tape recorder.

Mark might have revered Stevenson as a pioneer. Stevenson, in turn, might have considered Mark a crackpot. He wore a cheap silver necklace and a credulous expression, spoke with a stoner’s cadence, and drove a white Chevy TrailBlazer whose license plate holder read “Ghost Hunter.” Mark’s colleague, Chris, made a slightly better first impression, but only slightly. He asked me not to use his last name and, when I asked about his background, he showed me credentials he claimed were from the US State Department.

We spent two afternoons at the hotel. The building stood at the intersection of two railroad lines; more than 900 soldiers, Union and Confederate, had died there. As we moved from room to room, Mark elaborated on the building’s history, which made our investigation seem more like a publicity tour for the hotel. When the history lessons stopped, we silently ran our tape recorders for minutes at a time, to collect audio samples that we ran through digital filters on Chris’s computer.

“I can’t tell you 100 percent what’s going on,” Mark told me one afternoon. “All I can tell you is, what I do doesn’t make any sense when I get some of these recordings of voices.”

I showed him my tape recorder, tapping the red “record” light with my finger. “So, hypothetically, I could be getting something?”

“You could be getting something on that. It wouldn’t surprise me.” That makes one of us, I thought.

Near the end of our two weeks, I went alone to Chris’s house, down the street from the hotel, to review some of the audio I’d recorded. We spent 30 minutes on three minutes of tape; Chris amplified high-frequency sounds, and lowered the low-frequency noise. “Did you hear that?” he asked occasionally. His computer speakers played back a few short sounds, pops and crackles, but nothing that approached human speech.

“Were you earnest?” Chris asked me after we’d finished reviewing my audio files. “Were you open? Did you believe yourself, asking your questions in mid-air?”

During the weeks I spent with Mark and Chris, I also began reading research and stories by Stevenson and his colleagues—about Jinadasa and Purnima, Dolores Jay and Gretchen Gottlieb, the combination lock Stevenson kept in his desk drawer. I tried to contact Stevenson’s colleagues. I emailed people who research deathbed visions and near-death experiences. I left voicemails and asked to speak with men and women who study altered states of consciousness, out-of-body experiences, accounts of past lives. Each request was either politely declined or went unanswered.

Stevenson’s colleagues typically will not respond to questions about their work from journalists. Though part of a public university, the Division of Perceptual Studies offers no classes. The small staff does not recommend psychics or hypnotists; its website carries a note from Stevenson that cautions against hypnotic regression—the tactic that Rev. Jay used on his wife to summon Gretchen Gottlieb.

Direct access denied, I requested an appointment to visit the division library—“a well-stocked library of scholarly books and journals on paranormal phenomena” and, according to its website, one of only a few such collections in the world. I received a response from the librarian, who also studies past lives and near-death experiences.

“I can let you in the library for a while to do your own research,” she wrote.

She must have consulted with her colleagues, however, because she sent another email the following day. She wrote that “the press has trivialized our work here ... for entertainment purposes, and we are very wary of this sort of thing happening.”

Stevenson’s work attracted an eclectic mix of enthusiasts. Carl Sagan said past-life memories like those collected by Stevenson and his colleagues “deserved serious study,” and the psychiatrist Harold Lief said Stevenson’s work could make him “the Galileo of the 20th century.” The man who invented the technology that birthed Xerox was a major supporter of the Division of Perceptual Studies. Perhaps Stevenson’s most generous supporter, however, was a silent film actress named Priscilla Bonner.

In 1920, Bonner moved to Los Angeles from Washington, DC, to become an actress. Her characters often suffered the pains of patience. She played the burdened single mother who shared an apartment with Clara Bow’s capricious knockout in It. In two Frank Capra films—The Strong Man and Long Pants—Bonner plays the fated love of Harry Langdon, first as a blind woman who strives to recognize the soldier she sent wartime letters to, then as a childhood sweetheart whom Langdon attempts to shoot before their wedding.

Bonner played her final role in Girls Who Dare, and then retired from film. She had married Bertrand Woolfan, a medical student from Chicago turned celebrity physician. They bought a home in Sunset Hills—a Spanish villa that acquaintances likened to a castle. When asked about her retirement, Bonner said she chose her husband over her career. However, in 1927, The Jazz Singer broke the silver screen’s sound barrier and took in nearly $4 million at the box office. One writer argued that Bonner’s voice “was not ideally suited to talkies.” She maintained otherwise.

As Bonner’s name receded from headlines, Woolfan’s health steadily declined. The actress’s husband suffered back pains that left him, he claimed, a “hopeless cripple.” When he was 67 years old, Woolfan explained to Bonner that he preferred death to pain. On Dec. 26, 1962, Woolfan composed a suicide note, retrieved his .35-caliber handgun, and shot himself in the chest.

Bonner called police to report his suicide attempt and admitted medical attendants to their house, but Woolfan sent them away.

“I have diagnosed my wound and it will kill me,” Woolfan said. “My lung is filling up with blood and I am dying. I wish to die at home.” Someone gave him a painkiller, police and medics waited outside the castle walls until Bonner summoned them inside to declare her husband dead.

Bonner buried her husband in Enduring Love, a section of the Forest Lawn cemetery. She outlived him by more than three decades, never remarried, and never returned to film. In her nineties, she moved into a retirement home in Beverly Hills. When a reporter tracked her down and asked her about Woolfan, Bonner called her late husband a “remarkable man,” though she added, “There’s nothing good about being old.”

One night over dinner, I asked my wife whether she’d be disturbed if I tried to contact her after my own death.

At 97, Bonner planned a dinner party for a few friends. She set a date—March 30, 1996—and promised to pick up the bill. However, Bonner never made the party. In the Queen of Angels Hospital, one month before the date, she instructed a friend: “Tell the boys I won’t be able to have the dinner.” She died five miles from the castle she shared with Woolfan, and a few miles more from Forest Lawn cemetery. Other internment sections had come available since Woolfan’s death—Peaceful Memory, Courts of Remembrance—but Bonner was buried beside her husband in Enduring Love.

Bonner’s interest in Ian Stevenson’s work emerged in the papers after her death. An obituary in the Los Angeles Times said Bonner “believed in the survival of human personality after physical death,” and directed memorial contributions to the Division of Perceptual Studies. In her will, Bonner left $2.6 million to fund Stevenson’s research.

I found no links between Woolfan’s death, Bonner’s financial support, and Stevenson’s work. Still, it seemed like a strong coincidence. Perhaps Bonner hoped her husband, as Stevenson had theorized, would reach out to her after his death, speak to her as he once had.

Or maybe Bonner hoped to attain immortality herself, through some means other than her Hollywood work. As I watched Bonner perform in Capra’s films—each character infinitely patient, timelessly beautiful, utterly silent—I wondered what comfort a lasting body of work brought her. Actors inhabit other lives for weeks or months at a time then leave them behind. One of film’s great thrills is the recognition of a familiar person in an unfamiliar character. I imagine it’s the same thrill Stevenson experienced in his own work. It’s also the one I most desired to experience myself.

I replayed both of Bonner’s films dozens of times. In Long Pants, Harry Langdon, Bonner’s co-star, plays an immature man-boy seduced by mobster fantasies. He approaches Bonner, his patient fiancée, his enduring love, in coattails, top hat, and cold feet, and asks her to join him for a walk in the woods. Langdon tries three times to draw his revolver and shoot his fiancée, but fails; each time, Bonner turns around before he can draw. She approaches him, incandescent in her white gown, as Langdon tells her to stay put. “Count five hundred,” he mouths as he readies his gun again, “and hold still.”

After I hit “rewind” on that one a dozen times, I switched to Strong Man, in which Bonner plays a blind woman whose letters to Langdon’s soldier win his heart and pull him from battle to her hometown to find her. Langdon approaches Bonner again. Ecstatic at the sight of her, he begins to peacock. He dances and struts before her, pushes his jacket out, walks on his heels. Then he stops, smiles, and asks, “Aren’t you surprised to see me?” No, I thought. Relieved, actually.

Years after Bonner died, the castle she shared with Bertrand Woolfan went up for sale. Realtors created a video tour of the home—a series of still photographs that the camera slowly drifts toward or away from. Two stone lions stood watch on either side of the heavy wooden front door. Tiered swimming pools dominated the backyard, their levels maintained by a series of waterfalls that emptied unceasingly into the next lake. The camera moves through the formal dining room, painted a royal blue that, at night, must dim to the somber tones of Picasso’s “La Vie,” then suddenly shows a mint-green kitchen. Each room dissolves into the next, which gives the feeling of passing through walls.

I had hoped that a glimpse at Bonner and Woolfan’s home might reveal something about the couple’s interest in past lives and reincarnation research. I wanted a sign that the couple had learned to negotiate their future as nimbly as they could discuss their past—to move in time as they did in space, to somehow reach the next room though no doors go there. But nothing within the castle resembles the home that Bonner would have kept with Woolfan. For all my desire to scale walls and open locks, I had no more perspective than the neighbors whose homes surrounded the castle and who, noting the “For Sale” signs along Queens Road, might speculate who will move in next.

One night over dinner, I asked my wife whether she’d be disturbed if I tried to contact her after my own death. “I don’t think so,” she said. We bought my combination lock the next week.

I like to think my approach to death is a logical one, steeped more in science than in religion. Albert Einstein called death “the most unjustified of all fears, for there’s no risk of accident for someone who’s dead.” What I fear—a fear that Stevenson and Bonner perhaps shared—is the loss of a world in which I can enjoy the love of those closest to me.

After I bought my lock, I wrote to the Division of Perceptual Studies and asked whether they still accepted submissions for Stevenson’s combination lock test. A few days later, I received a note in response, from the librarian I’d spoken to years earlier:

Dear Brendan,

Yes we are still accepting submissions for the lock. Please send it on to me and I will submit it to the researchers. We thank you for your interest in the research being done at the Division of Perceptual Studies.

I haven’t decided what to do with my lock. “A recently deceased person who survives death will have many new experiences to assimilate and many things on his mind apart from the combination lock that he set,” Stevenson wrote. “So will the persons he has left behind.” I’m tempted to send it to Stevenson’s colleagues, but their work matters less to me than my wife does. What I most want is some assurance that I can find her again and again, approach her in different roles and characters, as Harry Langdon does Priscilla Bonner. I’d like to dance for her again, someday, ecstatic in my love, and ask her, “Aren’t you surprised to see me?”