The Downstairs Gays

Social media makes it easy to virtually tour our neighbors’ homes—and really, their entire lives. The hard part: finding the clear divide between entertainment and cyberstalking.

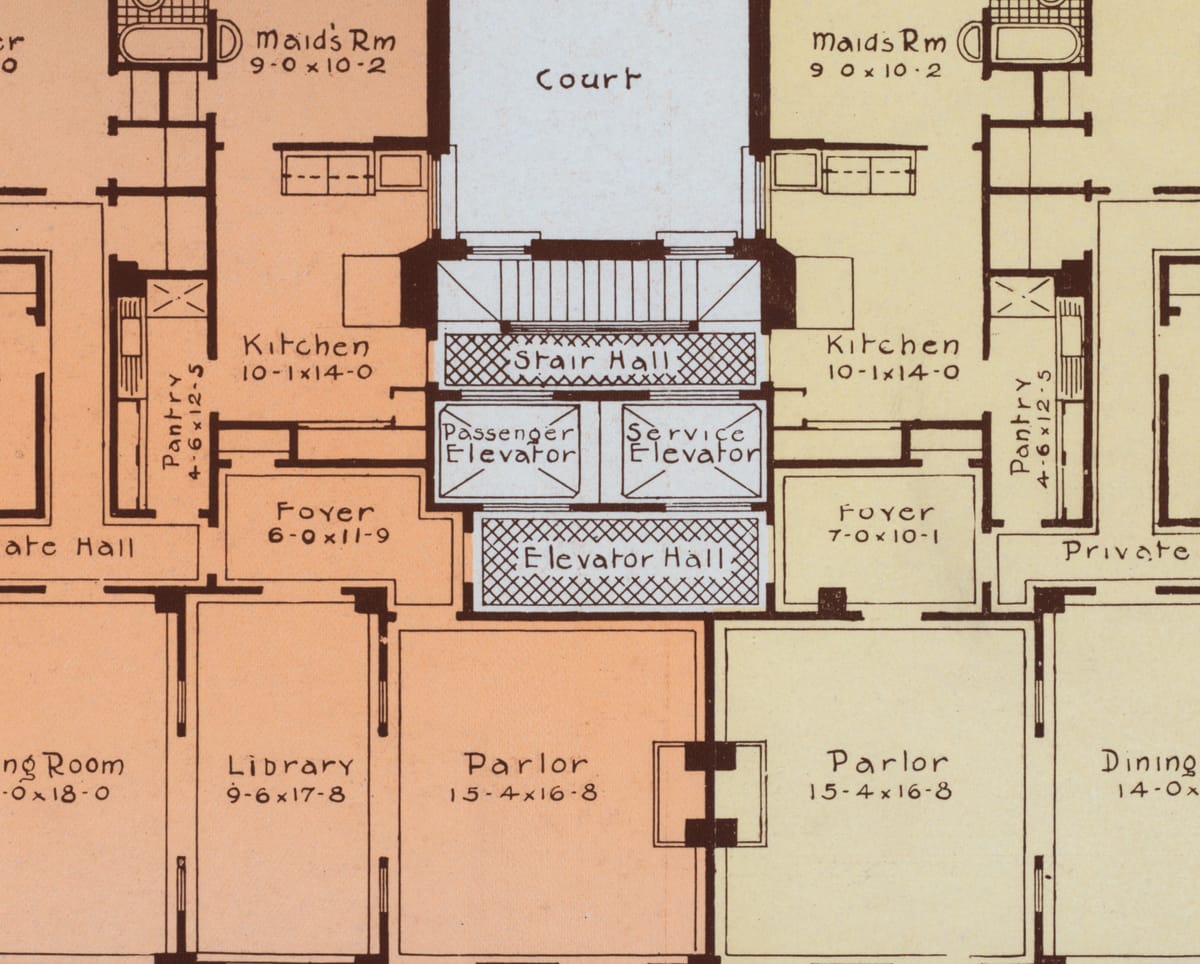

One afternoon about a year ago, I found a CB2 catalog in my mailbox addressed to one of my downstairs neighbors, a well-heeled gay couple in their early 30s. The super told me when I moved in that their apartment was twice as large as mine, and included something he called a “double kitchen,” whatever that is. Our building was one of those with a storefront on the first floor and apartments above designated “F” and “R” for Front and Rear. I lived in number 2F; they lived in number 1.

I spent my first few months in 2F wondering how to befriend the gay couple with the double kitchen, whom my roommate and I started calling the “Downstairs Gays.” I couldn’t ever think of a normal reason to go down and say hello, and with each passing day a “Hi, I’m new here!” introduction felt more and more contrived. I’d met the gluten-free vegan in 3F and the meek, pasty cat guy in 2R, but I could hardly get excited about either one—they were no better than me, humble peons of the single kitchen.

I ran into one of the Downstairs Gays on my way into the building one Saturday, a few weeks after I moved in. He was dressed head to kneecap in the Lycra gear that separates cyclists from mere bikers. He introduced himself as we climbed the stairs, his DayGlo track bicycle hefted onto one shoulder, but the only thing I could focus on was the fact that his face was at my butt level, an awareness that made me a poor conversationalist. If I’d been thinking strategically, I might have asked him out for a neighborly drink, something to cement our interaction, but instead I scurried my self-conscious butt higher, past his door, and we entered our respective apartments uncemented.

My boyfriend had been pestering me up until then to bring them down a bottle of wine or a pie to curry neighborly favor. His apartment curiosity had begun to rival mine since we’d discovered, peering down from the roof, that their apartment also had a back deck, draped in ivy and standard-issue Brooklyn backyard globe lights.

Now, several weeks beyond a reasonable welcome-pie threshold, CB2 catalog in hand, I climbed the stairs from the mailboxes and wondered idly about just which neo-modern arc lamp they’d selected for their living room. I laid the catalog neatly on their welcome mat, face-up. But in the brief flight, I couldn’t help but note the last name on the mailing label—the first name matched the cyclist who’d introduced himself to my butt. Once inside my apartment, I couldn’t help but Google it.

In a dozen keystrokes and two clicks, I’d gained access to more specific information about my downstairs neighbor than I have about most of the people I actually know.

It was a unique enough name that the first hit was his Twitter account; the second hit was his website, [hisname].com, which featured a sidebar of links, including his Twitter, his Instagram, his résumé, his portfolio, his Tumblr, his Pinterest, his LinkedIn, his Vimeo, YouTube, and SoundCloud likes, as well as links to a few “obscure Netflix faves” and several TED Talks he’d enjoyed. Ironically, the only link not listed was his Facebook—perhaps that would have been too personal.

In a dozen keystrokes and two clicks, I’d gained access to more specific information about my downstairs neighbor than I have about most of the people I actually know. The extent of my hope in googling my neighbor had been to find out what he did for work, and to marvel at how he and his cohabitant could afford such an enormous apartment. I thought at most I’d find his Facebook, and maybe find out whether the two of them were married. Within an hour I’d learned they weren’t, but could pinpoint their upcoming nine-year anniversary within a matter of days. With a single scratch, I’d opened a gushing wound of auto-reportage, learning answers to questions I never would have thought to ask about a pair of strangers. Now that I’d found what I’d found, however, my curiosity was catching up to my knowledge.

I had an impulse to fetch the catalog from their doormat and reserve returning it for a time when I was sure they’d be home—finally, I might have a reason to talk to them. I briefly imagined what I’d say. Hi, sorry to bother you, but this was in my mailbox and I accidentally brought it upstairs with me. Oops! Say, is that the Big Dipper Arc Floor Lamp from page 9? No. I’d give myself away immediately as an over-interested creep. A CB2 catalog hardly seemed worth saving longer than a single trip to the bathroom, much less hand-delivering to a stranger. I decided to leave it.

Unfortunately, though, because I had nowhere else to be that afternoon, and because the internet is shaped like a whirlpool, I was slipping deeper into the eddy of the Downstairs Gays internet. Downstairs Gay #1—the one I’d met, whom I called Mustache after the truly awful blond shape floating above his upper lip—worked in tech, as did Downstairs Gay #2, whom I just called Brown Hair. He seemed super boring, to be honest—he had no discernible web presence, aside from an empty Twitter and a school-picture-day LinkedIn profile picture—and had few distinguishing features, except that he was way cuter than Mustache. Mustache’s Twitter was mostly boring tech-industry nonsense and links to his Instagram. His Instagram was gold.

Alone in my apartment, the sun setting slowly between the buildings across the street, I loaded page after page of vacation photos, wedding snapshots, and selfies around the city. I saw the Downstairs Gays on bikes, on Fire Island, on their back deck, and on a Grand Tour of Southeast Asia, for which they’d invented an unpronounceable hashtag. I watched their hairstyles and outdoor hobbies ebb and change with the seasons. Nestled among these mementos of glamorous, moneyed couplehood, I caught the first glimmer of what I’d been looking for: a photo of their apartment.

Technically, it was a photo of the luggage they’d packed for their unpronounceably hashtagged Southeast Asian vacation. But underneath the luggage was gorgeous parquet inlay bordering diagonal hardwood. It was perfect.

It was like an HGTV special in the form of a scavenger hunt, built only for me.

I continued my journey back through time, scanning for interiors, noting the moulding, the paint color, the carpet, and the mid-century furniture. (I probably should have confiscated that CB2 catalog, to be honest.) It was like an HGTV special in the form of a scavenger hunt, built only for me. I pored over their second living room—the same space occupied by both bedrooms in my apartment, one floor up—and the lush expanse of their back deck, where I saw them picking cherry tomatoes and relaxing with beers and houseguests.

When my roommate came home a few hours later, I’d worked myself up into a thick lather. I’d neglected to turn the lights on after sunset, and she walked in to find me sitting in the cold bath of a laptop screen in one corner of the living room—our only living room—babbling about hairpin furniture legs and crown moulding and how come we didn’t have any? I told her about the catalog and the arc lamp and the parquet and the second living room, and pulled up a picture of a truly horrendous wall treatment they had DIYed in what I had by then determined was the dining room, involving old Sears catalogs decoupaged inside frame mouldings. In another room, double-frame mouldings featured a triple-layered treatment of matte black wall paint, high-gloss white, and loud black-and-silver floral wallpaper—it was Jo-Ann Fabrics boudoir chintz. It was awful, and I was in thrall.

My roommate seemed alarmed at the amount of information I’d been able to gather about the Downstairs Gays in a single afternoon, but was nonetheless shamelessly intrigued. We discussed the attractiveness of each half of the couple—she agreed that Brown Hair was way too cute for Mustache—and lamented that nowhere along our respective career paths had we decided to go into tech. If I’d known it would come with such charming original details I might have seriously considered it. (I mean, the parquet alone.) Still no sign of the double kitchen, in any case.

One post was a photo of the back of a postcard, thanking the Downstairs Gays for a lovely weekend; the caption referenced their “wonderful Airbnb guests.” Without consciously boarding this train of thought, within about five seconds I’d hatched a plan to install a disconnected friend as an Airbnb guest at the Downstairs Gays’ apartment, where we’d see once and for all what this double kitchen was all about, and taste the cherry tomatoes of victory from the lambent late-evening light of their private deck.

The Downstairs Gays were living the gay life I’d dreamed of living ever since I internalized that living well might be the best revenge for a difficult adolescence.

I was starting to feel like Judi Dench in Notes on a Scandal—in a bad way. I closed my laptop, poured myself a mug of wine, and ran a shower.

I tried to unpack the obsession I’d stumbled into. I chalked most of it up to a decade or so of HGTV, of consuming living spaces as intensely and invasively as most people consume pop stars and Real Housewives. The gulf between my life and the Downstairs Gays’ life felt narrower than your average HGTV experience, since we shared 80 percent of a street address, but in a sense it was more extreme, our proximity serving only to highlight my relative real estate shortcomings.

The Downstairs Gays were living the gay life I’d dreamed of living ever since I internalized that living well might be the best revenge for a difficult adolescence. From the hardwood to the track bicycles, the Downstairs Gays were a photogenic wonder of homosexual living with a dual income and no kids—ill-advised wall treatments notwithstanding.

Months passed, the cherry tomatoes died, and neither I nor the Downstairs Gays made any overtures toward friendship IRL. Their apartment went quiet for several weeks last winter, and we worried they’d moved, but their Instagram meanwhile told another of its grand, globetrotting sagas, this time in a difficult-to-identify sun-soaked wonderland.

They became a casual fixture of my apartment. When friends came by, I’d share the latest on their comings and goings, like a soap opera recap—a trip to Fire Island, a new couch. (I’m not being stereotypical; these are actual Instagrams.) Most of my friends, I’m sure, found my casual updates strange, if not outright creepy, but they nodded politely in any case, and allowed me to continue.

The more I focused on the quotidian Instagrams of the Downstairs Gays’ lives, the less I considered how bizarre it was to be sifting through the social media of a person I didn’t know, and who was not in any way styling himself as an Instagram personality. This was not his brand. It was just his life.

Under normal online circumstances, the notion of “stalking” as it’s commonly used—Facebook stalking, or Instagram stalking—seems to me overstated. It’s not a matter of hacking, or of breaking and entering anything; it’s often simply a matter of paying greater-than-passing attention to someone or something accessible through public channels, or at least channels to which you’ve been granted access, via friend request. Even the language we use—“friending” on Facebook, but “following” on most other platforms—underlines the stranger-based nature of the interaction. At a time when googling is standard operating procedure for a coffee date, how weird is it to follow the thread a bit further?

I moved out of 2F a few months ago to a less posh apartment farther east. My new living room has an airshaft view, which has presented one naked neighbor and one neighbor with a selfie habit—far more embarrassing than nudity, in my opinion. I miss the neighborly intrigue of my old apartment, but the gift of the internet means I haven’t had to leave the Downstairs Gays, not entirely. I still look them up every once in a while, just to see what exciting vacations they’ve taken, what fresh, high-gloss Hell they’ve applied to their interiors. They’ve been making preparations for Burning Man, and I could hardly ask for more, content-wise. They are, at least, internet strangers at a more appropriate remove now. Though I still know where they live.

In certain moods, I flatter myself that they might have been keeping tabs on me, too. That in my squirrelly unfriendliness, I might have inspired some malicious curiosity about just what I, with my ripped jeans and tote bags, was doing in their building, they of the Dual Income and No Kids. I wonder if some mislaid issue of the New Yorker may have opened me up to googleable scrutiny; I wonder, once this ode to the Downstairs Gays—my Downstairs Gays—is published, if they might find it, and whether they’ll recognize themselves if they do. If they can help being deeply disturbed, I wonder whether they might feel a tinge of sadness at my absence, and a well of gratitude that we can still know each other, without knowing each other, from afar.