The Marlboro Men of Chernivtsi

Where there’s smoke, there’s smuggling. Before the Ukrainian border became a dangerous war zone, it was a profitable bootlegging arena.

The 7:10 a.m. bus to Suceava was almost entirely empty and quiet. Well, except for the bus driver. With foamy spittle amassing on his lips as he spoke in a language I couldn’t understand, he kept thrusting a carton of cigarettes in my face, waving it wildly. And with each new response from me—all versions of “No, thank you” in any language I could butcher—both the cigarettes and the spittle came closer. My girlfriend, Erin, sitting next to me, was just as perplexed.

We’d arrived in Chernivtsi, the largest city in southwestern Ukraine, the afternoon before, and now were on our way to Romania. In the summer of 2008, well before Ukrainian borders were crossed by invading Russian troops, we didn’t think much of what lay ahead of us. We’d been bouncing around Eastern Europe for three weeks and figured our jaunt into Romania would be a forgettable affair.

“He doesn’t want to sell you the cigarettes,” a brown-haired man declared in British-accented English. “He wants you to take them across the border for him.”

With this, the driver sensed an opening and stopped waving the carton at us.

“Take them?”

“Well, he wants you to put the carton of cigarettes in your bag for him. He wants you to help him smuggle the cigarettes across the border.”

“Smuggle?”

“I guess that’s the technical term,” the British man laughed. “But I wouldn’t worry about it. It’s quite normal. This is the way things work here.”

Feeling peer-pressured in ways I hadn’t since I was 13 years old, I saw I had little choice. I couldn’t claim I didn’t understand what was happening, and now this episode had received the green light from a fellow English-speaker. Even if I wanted to say no, it didn’t seem like the bus driver was going to take no for an answer, and this was the only bus of the day. With a shrug from Erin—this was normal, right?—I accepted the cigarettes from the gleeful bus driver, opened up my backpack, and stuffed the carton of Marlboros inside.

What’s the big deal, I thought? I was just doing this bus driver a favor—all part of the international experience. How serious could taking a carton of cigarettes across the Ukraine-Romania border be?

In 2015, the dominant news stories about crossing the Ukrainian border involve armies and weapons. From the east, the Russian army has already marched into and annexed Crimea. The furious fighting right now in Donetsk and Luhansk, both near the border with Russia, has Western leaders perplexed over how to stop the bloodshed and secure Ukraine’s sovereignty. But before the Ukrainian border became a dangerous war zone, it was a profitable smuggling arena. And while weapons are now being smuggled across the border, the smugglers’ main product before this conflict broke out was cigarettes.

In 2008 Ukraine, the international cigarette companies that control 99 percent of the cigarette market there manufactured and imported 130 billion cigarettes. And for a country that adores smoking like few others—according to the Tobacco Atlas, the average Ukrainian in 2008 smoked 2,526 cigarettes—you’d have to assume that all 130 billion would be gobbled up by the populace. You wouldn’t expect, however, that nearly 25 percent of them were not.

According to the Tobacco Atlas, the average Ukrainian in 2008 smoked 2,526 cigarettes.

Officially, according to the four leading international cigarette companies in Ukraine—Philip Morris International, Japan Tobacco International, Imperial Tobacco, and British Americano Tobacco—30 billion cigarettes were “lost.” The reality was that these cigarettes were sold wholesale to international cigarette traffickers. According to Tobacco Underground, a group of journalists determined to uncover the rampant cigarette smuggling throughout the world, cigarettes are the most smuggled legal substance on earth. After the fall of communism, major players in the tobacco industry chose Eastern Europe for the expansion of the capitalist cigarette industry. During the 1990s, anti-smoking campaigns in the West were well underway, but this wasn’t the case in Eastern Europe. Smoking was ingrained in the communist culture and represented one of the few freedoms Eastern Europeans had. They weren’t about to give it up with the fall of the Berlin Wall. So Western cigarette companies moved in.

They weren’t the only ones who saw an opening in Eastern Europe, though. More daring than making profit from these “lost” cigarettes, one manufacturer in particular, the Baltic Tobacco Company, was established solely for the purpose of smuggling.

Ukraine’s tangled relationship with Russia makes it an interesting case study for how international cigarette smuggling works. The Orange Revolution of 2004-2005 represented the first time in modern history that Ukraine broke away from Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union. But as an impoverished state where the GDP per capita was $1,800 US in 2005, the break from Russia didn’t immediately lead to a better life for most Ukrainians. Between 2005 and 2015, Ukrainians have seen wild swings in their economic fortunes and the notion of a stable economy has seemed like an illusion. It comes as no surprise that a country with a flailing economy would have so many people turn to smuggling.

And cigarette companies, it seems, have been eager to play along. Seizing an opportunity in a country with some of lowest cigarette taxes in the world, international companies are thriving in Ukraine. But Ukraine wasn’t always the culmination of their cigarette market. There were smokers all over Europe, but in recent years, many countries had seen a decline in smoking because of the added cost of massive taxes on cigarettes, levied to give smokers a financial incentive to quit and young people no incentive to start. In Ukraine in 2008, a pack of Philip Morris Marlboros cost $1.05 US. In Romania, that pack of cigarettes would cost at least double. That pack could cost at least five times as much in Germany, and even farther west, in Great Britain, it could cost over $10 US.

The international cigarette companies in Ukraine had a different, unofficial plan: make money by selling cheap cigarettes with low taxes to a smoking-hungry population, and then add to it with extra sales of “lost” cigarettes to smugglers who would be eager to flood European markets with cheap, tax-free cigarettes.

This plan was humming along when I unknowingly joined it. The production of Marlboros—the most popular brand in Ukraine—rocketed skyward 85 percent from 2003 to 2008. A portion of these cigarettes were illegally smuggled on the European black market, which in 2008 was a $2.1 billion industry. By 2015, the numbers have become even more staggering. According to the European Commission, the EU loses 10 billion Euros annually in tax and customs revenue due to cigarette smuggling. And in a study conducted from 2006–2012, illegal cigarette consumption in the EU has spiked by 30 percent. Worldwide, cigarette smuggling now costs governments $50 billion US in lost revenue.

The cigarette companies sell the cigarettes wholesale to buyers, and in some cases they might be aware they’re selling to smugglers. In other cases, they might not. It’s always possible that any wholesale purchase could be for legal purposes, so for them, it’s not in their best interest to ask too many questions. And once the smugglers have the cigarettes, the only issue is how to get them safely across the border.

We settled in for the 75-kilometer ride to the Romanian border. Factoring in the bad roads and the crawl our 1970s bus would be chugging along at, we knew this ride would take several hours. But I still found myself surprised that every one or two kilometers, the bus would sputter its way over to the side of the road and out of the trees would emerge a small colony of overweight, elderly Ukrainian women.

At our first stop, five of them trudged onto the bus. Less than five minutes later, we stopped again, allowing a new group of grandmothers to board. This was followed by another stop to pick up more of these women.

When the bus had departed from the station in Chernivtsi, including us, there were only six or seven people on it. Now, after a mere ten kilometers, we were crammed to capacity.

The women were dressed in the typical fashion: headscarves; long, dark skirts; and baggy blouses dulled by years of wear. Their most notable aspect was their luggage: Each was carrying at least two—sometimes three or four—identical large black plastic bags with the same striking white typeface: BOSS etched on top with HUGO BOSS in smaller print neatly below.

The bags all seemed to contain the same rectangular objects, rounded out as the women stuffed items of clothing on top.

Money began changing hands on the bus. This would be a normal occurrence as people typically passed their fare forward to the bus driver, but here, the women weren’t exchanging Ukrainian Hryivna but US dollars, mostly $20 bills.

“Do you understand any of this?” I asked Erin, whose nose was in a book.

“Wait a minute,” she nodded in the direction of two women standing in the aisle adjacent to us, “what exactly is she doing? She’s not, she’s not—is she?”

One of the women was reaching down into her shirt and stuffing her bra full of packs of cigarettes. Once she’d sufficiently loaded up her bra, she moved to her skirt. More packs of Marlboros were headed for her underwear.

“Oh my God,” Erin whispered urgently. “They’re all doing it!”

This was a cigarette smuggling bus. Each woman now had two Hugo Boss bags, and each bag appeared to hold about eight cartons—1,600 cigarettes. Our quick math led us to believe there were around 500 cartons—100,000 cigarettes—on this bus.

The Romanian border had to be getting close, and these women were all gearing up for the crossing. This seemed to be the least devious act of smuggling I could imagine. Even if cigarette smuggling were normal, wouldn’t it also be normal to try harder to hide it? But maybe they knew something I didn’t.

And maybe I shouldn’t have been worried about how the women were concealing their stash of Marlboros when I was a part of it, too. With that thought, sweat started to trickle down my neck. I leaned down and stuffed my carton of cigarettes deeper into my backpack.

Though we didn’t know it then, using a medium-sized bus to transport approximately 100,000 cigarettes was a small-time scheme. From Ukraine, it wasn’t uncommon for hang gliders to take off near the border and float their way into Hungary or Romania. Once they hovered in the general vicinity of the drop spot, they’d release their cargo—hundreds, even thousands of cartons cigarettes—make a hasty turn, and head back.

Sometimes vans would be equipped with secret compartments underneath the floor and roof panels. Trucks legally transporting materials would save room for illegal cigarettes. Bigger smuggling operations employed secret panels inside liquid gas tankers, providing space for thousands, sometimes even millions of cartons. (The largest seizure of cigarettes of all time occurred in 2009 when 4.4 million cigarettes were found inside a tanker.) Boats would include space for secret cigarette cargo among their other legally transported goods. Shipments of fruits and vegetables could be littered with illegal cigarettes.

In 2008, 66 million cigarettes were seized by Ukrainian police and border officials: less than one percent of what was believed to be smuggled that year.

In 2012, Slovakian authorities unearthed a 700-meter-long underground tunnel crossing the Ukraine-Slovakian border used for cigarette smuggling. The tunnel even included a rail car system. And even worse was their speculation that this tunnel was used for human trafficking as well.

The rampancy of cigarette-smuggling isn’t just limited to faraway Ukraine. A 2014 study in New York state revealed that 57 percent of cigarettes smoked in New York had been smuggled into the state in order to dodge taxes. This led to a massive bust of 500,000 illegal cigarettes on Staten Island in November 2014.

Organized crime flourished with the introduction of the Eastern European illegal cigarette trade in the 1990s. These syndicates weren’t entirely responsible for the global trade of smuggled cigarettes, but the market was too good to pass up. Not only were there huge profits, the penalties for getting caught were light. The Ukrainian government’s punishment for cigarette smuggling amounted to a slap on the wrist. In 2008, 66 million cigarettes were seized by Ukrainian police and border officials: less than one percent of what was believed to be smuggled that year.

And the international cigarette companies in Ukraine didn’t actually mind when their product was seized. They had already claimed these cigarettes as “lost” and would receive no penalty. In fact, they’d typically receive a sales boost, as the smugglers would just buy more cigarettes from the manufacturer for another run. Cigarette companies actually profited from the authorities busting the smugglers; smuggling was part of their business model.

But this was only an issue when the Ukrainian government seized the cigarettes and arrested the traffickers, which in 2008 rarely happened. For the smuggling operation to work fluidly, border guards needed to be bribed to look the other way. The entire process had the potential to be so profitable to so many players that it’s easy to see why authorities were reticent to stop it. It starts with the cigarette companies who are eager to make a profit, selling 30 billion cigarettes wholesale to smugglers in Ukraine. (These “lost” cigarettes must be accounted for on the books somehow, but how this transpires is something that I was unable to account for in many hours of research.) The smugglers support themselves and their families. The border guards receive a nice boost to their monthly salary. The well-oiled system seemed to be helping all involved.

Worldwide in 2015, one in 10 people die prematurely from smoking-related illnesses. Eastern Europe contains some of the smoking-happiest countries in the world. The massive cigarette smuggling operations are contributing to a global public health nightmare. According to Tobacco Atlas, the illicit tobacco trade has now become more lucrative than drug trafficking.

As we pulled up to the official Romanian border, the grandmas grew quiet. I could tell they were nervous, and this was rubbing off on me.

“Don’t worry,” Erin reassured me, but even her voice was a little shaky. “I’m sure it will be fine. There’s no way all of them would be smuggling the cigarettes this obviously unless they know they aren’t going to get caught.”

The bus stopped at a customs gate so the Ukrainian border guards could inspect us and our luggage outside the bus. Out on the pavement, we stood in a single-file line. Erin and I clung tight to our backpacks while the smugglers clutched their Hugo Boss bags and smiled. Looking at their bags, there was no way anyone would believe they contained just clothing.

But none of this mattered. The guard glanced at us, lit his own cigarette, smiled, and then waved all of us back onto the bus, whereupon the women checked the cigarettes stashed on their bodies. The protruding packs made weird angles, but they didn’t seem too concerned. With a border guard who’d clearly been bribed to let us through, everything was certainly in order. This was just another day in southwestern Ukraine.

What’s happening on a regular basis on the Ukrainian border is happening on borders in other parts of the world, too. With 11 percent of cigarette sales worldwide coming through illegal sales of trafficked cigarettes, countries more powerful than Ukraine—and groups more powerful than the smuggling grandmas—play a vital role. In China alone, hundreds of illicit cigarette factories produce a whopping 400 billion cigarettes a year, with fake Marlboros being the most popular brand. Both Hezbollah and the Taliban count on their control of illegal cigarette trade to finance some of their terrorist activities. And even though fines for cigarette companies’ role in the illegal trade of their “lost” product have now eclipsed $1 billion, profits from the illegal cigarette trade are still much higher.

Closer to home, in Canada, police believe that there are 105 different groups—most related to organized crime—involved in smuggling cigarettes to and from the United States. In April of 2014, Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrested 25 people in Quebec as part of a smuggling ring that included 40,000 kilograms of illicit cigarettes worth roughly $7 million.

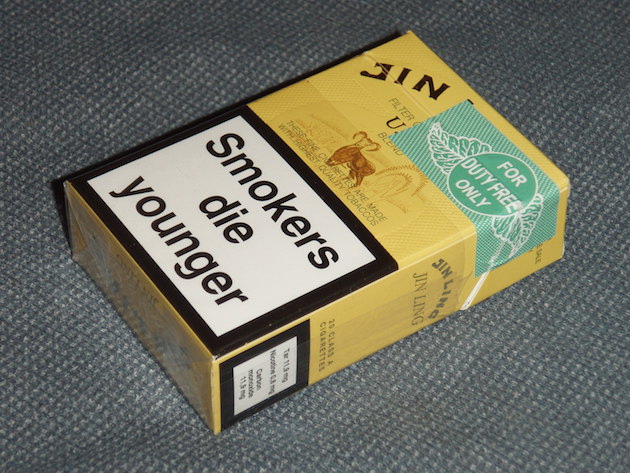

But there’s one particular company that seems to defy all sense of decency in the world—even in the shady world of cigarette trafficking. The Baltic Tobacco Company, located in the western Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, has been producing Jin Ling cigarettes since 1997. Jin Ling is known for its labeling and artwork, which are almost identical to the US brand Camel. The packaging is so similar, in fact, that if the cigarettes weren’t produced in Russia, I’m guessing Camel could sue for copyright infringement.

Jin Ling cigarettes are churned out at a clip of around 13 billion a year in Kaliningrad. And while this nets Baltic Tobacco an annual profit of about $1 billion, the cigarettes have no legal market. The Jin Ling brand is intentionally manufactured, transported, and sold exclusively by cigarette traffickers. While other cigarette companies might knowingly partake in the illegal cigarette trade on the side, they all rely primarily on legal sales. Baltic just skipped that part.

Perhaps this was a wise business move. In 2008, a container of Jin Lings—one container is 10 million cigarettes—would cost a little over $100,000 US. In Western Europe, that same container would be worth somewhere between $3 million and $6 million US. And with governments all over the world starting to crack down on smuggling, legitimate companies are feeling the heat. The fines are getting steeper and the PR fallout is starting to become more dangerous for business.

But Baltic is based in Kaliningrad, a haven for organized crime, and the Russian government doesn’t generally interfere with anything that goes on there. Baltic has yet to be fined, and even if international monitors were to step in, it would be difficult for them to do so. Baltic’s headquarters are hidden away with no signage on the building, and there’s a good chance that many Kaliningrad residents don’t even know the place exists.

Because they aren’t sold commercially, Jin Ling cigarettes are not well known in Russia, a country, like Ukraine, that loves its cigarettes. If Baltic Tobacco were to sell its cigarettes legally in Russia, the company would have to play by some of the government’s rules, and it has no interest in that. That’s because there are plenty of places where Jin Lings can be found all throughout Europe—all on the black market.

Jin Lings are in perfect position to be trafficked all over Europe. Kaliningrad is geographically separate from the rest of Russia, sandwiched between Lithuania and Poland with a sizable coastline on the Baltic Sea. Jin Ling cigarettes can easily be smuggled on land through Kaliningrad’s two former Soviet bloc neighbors. They have made it as far as Britain, and in case anyone needs a highly ironic reminder, all packs of Jin Lings have a duty free sticker on them. (They also don’t include any of the EU-mandated health warnings.) In Britain, it’s common for Jin Lings to be sold door-to-door in poorer housing developments or at convenience stores. Less officially, traffickers open their trunks and sell the cigarettes directly from their cars to customers.

In 2007, 258 million Jin Ling cigarettes were seized by European officials. But Baltic Tobacco isn’t simply dodging taxes. In 2012, a house burned down due to a woman leaving a cigarette unattended. All legally produced cigarettes must comply with a law requiring a cigarette to self-extinguish if the smoker leaves a it unattended. In this case, the unregulated Jin Ling kept smoldering and a 71-year old woman died in the fire. In 2014, in another raid of Jin Lings, officials discovered some of the cigarettes contained asbestos. But even with all these deterrents, Jin Ling production continues to increase—so much so that the apparent owner of Baltic Tobacco commented that the company is having trouble meeting the demand for its cigarettes. And, one can only assume, since Baltic has little to no interest in the Russian market, the Kremlin doesn’t see any need to do anything about this. As far as they’re concerned, Baltic Tobacco is a huge success story—a homegrown business that employs Russians and keeps the economy growing.

And in Ukraine and all over the world, there’s little doubt that cigarette smuggling is a way of life.

I’m guessing the grandmas would have far more misgivings crossing the Ukrainian border in 2015, no matter how desperate they were to smuggle their cigarettes. With fighting raging on for more than a year now in the eastern part of Ukraine, it’s difficult to even ascertain where the borders are anymore.

For all of us on the smuggling bus in the summer of 2008, we knew we’d have to cross the border twice: once on the Ukraine side and then again a few minutes later as we were about to enter Romania. For the Ukrainian grandmas, this second check was the biggest hurdle to clear.

Once we’d reached the Romanian border, the bus driver stopped and called out to the passengers. More hands shuffled and more US dollars were passed forward. A border guard rapped on the door to indicate that we should all exit the bus.

In Ukraine and all over the world, there’s little doubt that cigarette smuggling is a way of life.

Once again, we all gathered up our luggage and filed off. Unlike the quick Ukrainian border check, however, on the Romanian side, we waited for several minutes. I began to sweat once again, and this time, I could see that my fellow smugglers were sweating, too.

The first one to be searched was the bus driver. With the wad of greenbacks protruding from his back pocket—this had to be part of the plan, right?—he stepped forward once the three Romanian border guards showed up. Their black guns seemed to leap out at all of us. But maybe three men on the border patrol just meant that the total bribe money would end up being a little steeper.

When the first guard asked the driver to show him his Hugo Boss bag, I figured we were getting another up-close look at the sham of an international border check.

But the Romanian guard didn’t stop at the top of the bag. Removing a single sweater, he revealed the cartons upon cartons of Marlboros beneath it. Furious, the guard started shaking his head. The bus driver started talking to him, pleading with him, but the guard was having none of it. He yelled at the bus driver, who appeared to be trying to plead his case. I wondered if the American money in his back pocket would come into play.

Instead, another guard confiscated the bags and banished the bus driver back to the line. His head down, he retreated as the first woman was summoned forward.

“I don’t think this is going well,” I whispered to Erin, looking at my own backpack on the pavement and trying to ascertain if my carton of Marlboros was visible from the outside.

More yelling followed from the border patrol. They’d taken the clothes off the top of the grandma’s Hugo Boss bag, too. She was berated and then dismissed without her cartons. I could see tears streaming down her wrinkly cheeks.

The border patrol stopped after the third smuggler’s bag was searched, and summoned over two more guards. The five of them stood next to the piles of Hugo Boss bags they’d confiscated, seemingly discussing how to handle the situation. They hadn’t inspected any of the women’s bodies, but the plastic bags contained the great majority of the cigarettes. Part of me wondered if maybe this was still part of the plan; maybe the guards were using this as a tactic to extract an even larger bribe.

“Please tell me,” Erin said quietly, “they’re not going to check your bag.”

The meeting of the border patrol broke up, and two of them headed right for the middle of the line, where Erin and I were standing with the British man.

They were coming for us.

In the same authoritative tone, the guards pointed at us and roared, “BAG-GAJ! BAG-GAJ!”

Terrified, I looked down to my two bags in front of me and did the only thing I thought might save my skin: I grabbed the smaller, cigarette-free bag and offered it up to the border guard. He interrupted me with his booming, irritated voice.

We had no idea what happened to the rest of the smugglers; were they fined, jailed, warned, barked at, or just left on the side of the road?

Oh shit, I thought. I’m screwed.

But as the guard continued yelling, I could see that he wasn’t looking at me anymore; he just kept pointing to the bus.

“Hey,” I said, “I think he’s telling us we can go back to the bus.”

“Are you sure?” Erin countered.

The pointing continued, and the British man chimed in.

“Yeah, I think they’re telling us to go—telling us to get our bags and head to the bus.”

With this, the guard nodded his head. I grabbed my bags and tried to act like I wasn’t about to flee wildly. Once back on the bus, we quietly settled into our seats.

Erin was the first to speak.

“I can’t believe what’s going on. Can you? What in the world is going to happen to all of them?”

“I have no idea,” I responded as I shoved the backpack containing the Marlboros as far under the seat as I could.

Of course they were breaking international laws, but these weren’t exactly hardened criminals. Their smuggling was only a drop in the bucket of much larger worldwide operations. The cigarettes they intended to sell in Romania for probably double the price they’d purchased them most likely helped feed their families. And from what I’d seen in Ukraine, there wasn’t an abundance of economic opportunities for women like them. While they were clearly committing a crime, knowing that they were in the process of getting caught, I started to wonder if I saw them as the victims.

A few minutes later, the grandmas started to rejoin us on the sweaty bus. The first came flying up the stairs in a huff, peeling away at the layers of clothing on her body, revealing a multitude of Marlboro packs fastened to her arms as she headed to the back.

In all, only seven or eight of them returned. These were the best disguise artists, as far as I could tell. The remainder—at least 30 women—we never saw again.

The last person to re-enter the bus was the driver, also looking relieved. He wiped his face and headed straight for me.

“Cigareta! Cigareta! Cigareta!”

When I withdrew the Marlboros from my backpack and handed them to the driver, he held them so close to his face that I thought he might kiss the carton. It was the only one of the 500 we’d left Ukraine with to make it across the border. As he marched to the front of the bus, I noticed his pockets no longer contained any US dollars. But he was focused on the glory of his one carton of cigarettes—a carton that might net him $10 of profit in Romania. For a country where the average annual income per person in 2008 was around $3,900 US, that one carton of cigarettes certainly meant something to the bus driver. By the time 2015 rolled around, the per capita GDP was exactly the same in a country that’s struggling mightily to move forward economically. Every pack of smuggled cigarettes counts.

We had no idea what happened to the rest of the smugglers; were they fined, jailed, warned, barked at, or just left on the side of the road? Perhaps Philip Morris had a shuttle ready to pick them up and take them back to the factory so they could buy more cigarettes. Perhaps they’d dive back into the smuggling ring. This was, after all, a profitable business when you didn’t get caught.

The driver started the engine and we rattled along the bumpy Romanian road. As he swerved to avoid potholes, he lit a cigarette and started puffing away. I still didn’t understand the appeal; at the age of 29, I’d never even smoked a cigarette.

The green, hilly forests of northern Romania whisked by us as we gazed out the window. We passed a dilapidated farmhouse painted a faded red. In the distance, an older woman was bent over, working in the fields. As she glanced up at us and waved, I wondered which brand of cigarettes she smoked.