The Moroccan Deception

A man follows his grandparents’ trek to Morocco—where the Alaouite Dynasty has ruled since 1666—to search for so-called “sacred music” amid a feedback loop of riots, arrests, and the promise of miracles.

In the fall of 1951, France replaced its Resident General in Morocco amid growing unrest and demonstrations across the country. General Augustin-Léon Guillaume, a battle-hardened soldier who first served in Morocco in 1919, was appointed in August with a mandate to keep the peace and suppress resistance to French rule. “Fighting is my business,” he announced upon his arrival. As for the Istiqlal, the country’s growing Nationalist party, he said, “I will make them eat straw.”

That winter, strikes broke out in cities across Morocco. Guillaume, determined to maintain French authority, hatched a plot to overthrow Sultan Mohammed V and install a monarch more amenable to the French Protectorate.

The sultan and the nationalists had much in common—the advancement of women, the establishment of trade unions, the broader aim of modernizing Moroccan society. But the French preferred to keep the country in a quasi-medieval state, divided internally and dependent on France. Guillaume’s predecessor, General Alphonse-Pierre Juin, advanced this policy by routinely allying with reactionary forces. Just before Juin’s dismissal, he sent an army of Berber tribesman to encamp under the walls of Fez in a show of force against the sultan.

Guillaume was worse. During World War II, he trained and commanded regiments of Berber goumiers, auxiliary mountain infantry units deployed in Europe and later accused of mass rape and other war crimes during the invasion of Italy. Months after Guillaume arrived in Morocco, government troops clashed with nationalists in Casablanca, leaving six dead. During riots in the city a year later, the death toll reached 400.

At that time, my grandfather was building an airport in Casablanca, working for a construction company under contract with the French Protectorate. He slept in a work camp near the construction site until apartments for families of the American workers were completed in the fall. My grandmother arrived in Casablanca in October 1951, six months pregnant. She had crossed the Atlantic alone from New York to Gibraltar on the Saturnia, an Italian passenger ship, then took a smaller boat to Tangiers, and finally a small plane from Tangiers to Casablanca.

My mother was born in Casablanca on January 4, 1952. A month earlier, the Moroccan unions, supported by the Istiqlal, called for a general strike. A few Europeans and scores of Moroccans were killed amid demonstrations; hundreds were arrested or expelled.

In August 1953, Guillaume deposed and exiled the sultan, and the country’s smoldering unrest exploded into violence. Lynchings and shootings broke out in Casablanca, the most politicized city in Morocco, where my mother and grandparents had been living. Even before the sultan's exile, my grandmother remembers riots, mass arrests, and public beheadings in the streets and squares of the city. They left as soon as they could.

The Alaouite Dynasty has ruled Morocco, with few interruptions, since Sultan Moulay al-Rashid bin Sharif was proclaimed Sultan of Morocco at Fez in 1666. Morocco’s royal family is one of the oldest and wealthiest in the world, whose current head, King Mohammed VI (grandson of Mohammed V), still rules as a genuine sovereign, wielding vast legislative and executive powers.

A protest movement sparked by the Egyptian revolution and the upheavals of the Arab Spring arose in Morocco in early 2011. In response, Mohammed VI hastily pushed through a new constitution and a series of reforms that seemingly preempted a violent revolt. There is now talk of a “Moroccan exception,” the notion that the country is immune to the forces that brought down long-standing regimes in Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt. Some say Morocco should stand as an example of how other Middle Eastern and North African countries can transition to democracy and escape civil war and revolution, and that the United States should draw closer to the North African kingdom and embrace it as a strategic ally in the region.

The average per capita income in Morocco is now about $4,500. The daily budget of the king’s 12 palaces is thought to exceed $1,000,000.

The grievances that sparked mass protests in Egypt’s Tahir Square—unemployment, poverty, rampant corruption—are the same as those behind Morocco’s February 20th Youth Movement, which led large protests in every major city during the Arab Spring, demanding an end to corruption and calling on the king to step down as head of the government.

Although it enjoys a better reputation in the West than its neighbors, Morocco is an impoverished country ruled by what Moroccans call the makhzen—a cabal of powerful businessmen, wealthy landowners, and high-ranking military officials close to the king and his entourage. The makhzen constitute what is essentially a shadow government, led by the king, whose family is at some level involved in nearly every major industry and corporation in the country. Corruption is a frank reality in Morocco but as long as there have been enough jobs to go around, most Moroccans have been willing to tolerate it—much like most Tunisians tolerated the dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and his family before they ousted him in January 2011.

But the deal only works if people can make a living, which is becoming more difficult to do. The country’s economic growth is slowing, in part because of its heavy reliance on trade with the eurozone. The average per capita income in Morocco is now about $4,500—the daily budget of the king’s 12 palaces is thought to exceed $1,000,000—half of what it was in Tunisia when the Arab Spring began. About 30 percent of Moroccans between the ages of 15 and 29 are unemployed, not counting those who have given up hope of finding work, while an estimated 40 percent of the population is illiterate.

For all his personal popularity, Mohammed VI is sometimes called “the king of the poor,” and his much-praised constitutional reforms have been criticized for being almost entirely cosmetic. Prime Minister Abdelilah Benkirane’s Justice and Development Party, a moderate Islamist party swept into power by the elections of November 2011, continues to serve more or less at the king’s pleasure, as elected Moroccan officials always have.

Every August in the capitol city of Rabat, political leaders participate in the annual ceremony of the Bey’a, or “celebration of loyalty and allegiance,” an elaborate affair in which they bow down before the king, swear fealty, and commemorate his coronation 14 years ago. The first such ceremony was held in 1934, to protest French rule.

Last year, the ceremony was protested by members of the February 20th Youth Movement, who staged a counter-protest they called “a celebration of loyalty to freedom and dignity.” Riot police dispersed the protestors by force.

I was in Morocco last summer during the World Festival of Sacred Music, held in Fez every June since 1994. The festival was founded by a group of Sufi Muslims to improve interfaith dialogue in the wake of the first Gulf War. That year, the festival’s theme was “re-enchanting the world,” which festival director Faouzi Skali defined in the festival program as “a means of refuting the current process of collapse and of reinstating mankind, culture and spirituality; of escaping from the all-encompassing economic diktat and rediscovering the freedom of the spirit. This could perhaps be the result of indignation at all that has gone before.”

A month before the festival began, a Moroccan court had sentenced a rapper, El Haqed (“the Enraged”) to a year in prison for insulting the country’s notoriously corrupt police with a song called “Dogs of the State.” A week later, police arrested 24-year-old poet Belkhdim Younes for organizing a sit-in to support El Haqed. The week after that, tens of thousands of people took to the streets of Casablanca to protest the government’s crackdown on artists.

But in Fez, the show went on. Most of the festival’s top sponsors were companies connected to or owned by the Moroccan royal family, like Attijariwafa Bank and Royal Air Maroc, and they did not want events in Casablanca to spill over to Fez. Likewise, the city’s merchants and shopkeepers rely on the surge of business the festival brings each year, and several locals told me that business owners made sure there would be no protests or sit-ins to disrupt commerce. With attendance already down due to the sluggish European economy, they could not afford demonstrations.

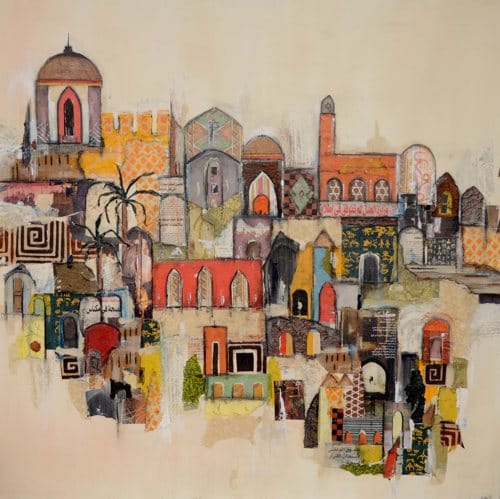

Fez is divided in two: the modern but crumbling Ville Nouvelle, built by the French in the middle of the last century, and Fez El Bali, the medina, or old city, founded by Idris I in the eighth century and now the best-preserved medieval city in the world. The medina’s streets are narrow and chaotic, sometimes widening to reveal a live-animal market or the entrance to a mosque, sometimes narrowing down to shoulder-width so that if you meet someone coming the other way, one of you has to back up.

As the festival drew near, the medina swelled with Europeans and Americans, who made up the core audience for the headliners, Björk and Joan Baez, both of whom kept silent about the arrests and protests in Casablanca. Lenny Kravitz and Mariah Carey would do the same a few months later at a major music festival in Marrakech, where they thanked Mohammed VI for inviting them to Morocco to perform.

On the last night of the festival I walked into the medina for a free outdoor concert in one of the city’s wide public squares, and on the way passed by the walls of the royal palace, where Mohammed VI stays when he is in Fez. Bored-looking soldiers leaned on machine guns in front of the palace gates, and I remembered something a tour guide told me a week before when I asked if tourists were allowed inside the royal palaces: “No, of course not. You would not have strangers come and tour your home, would you? It is the same with the palaces. They are the private houses of the king and queen. No one is allowed inside.”

Last fall, I visited my 83-year-old grandmother in Yakima, Washington. Over dinner, I asked about Morocco, and she got up from the table and came back with a scrapbook of old photos, ticket stubs, travel brochures, and postcards, all carefully arranged. She remembered everything—places they visited, names of friends and acquaintances, how she once rode in the rumble seat of their 1930s convertible when they took a day trip to Fez. She even had a photo of her and my grandfather sitting in the giant car, parked in front of Bab Boujloud, the famous Blue Gate of Fez.

They did not see the violence coming. It began very quickly, in Casablanca and also in Fez. But in Casablanca, she said, they were never in danger. The Moroccans were not interested in Americans; their fight was with the French and the Jews and the Berbers. I did not believe her, but I didn’t say so.

My grandparents left with my mother by ship from Tangiers in early 1953. They traveled to Paris and then sailed for New York via Southampton on the luxury ocean liner RMS Queen Mary. Back in Morocco, between August and December of that year, 53 people were killed in bombings, shootings, and train derailments in the major cities. On Christmas Eve, a bomb exploded in the central market of Casablanca, killing and wounding dozens.

Two years later, Mohammed V returned and successfully negotiated Morocco’s independence from France. In 1957, he took the title of King and ruled until his death in 1961. His son, Hassan II, succeeded him. Four years after taking the throne, he dissolved parliament and ruled directly for the next 34 years, surviving two assassination attempts in the early 1970s. Upon his death in 1999, Mohammed VI, just 36 years old, became king.

On April 28, 2011, a bomb exploded at a tourist café in Marrakech, killing 17 and wounding 24. Eight of the dead were French nationals. The government blamed the attack on Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, although Al Qaeda denied involvement. Nine people were arrested and charged, and that fall they were tried and sentenced. All of the accused maintained their innocence throughout the ordeal. The purported ringleader, Adel Othmani, was sentenced to death. He told the judge, “They’ve arrested an innocent man to sort out their own political problems.” The evidence against Othmani and his coconspirators was based solely on confessions obtained by police; the defendants claimed their confessions were extracted by torture. During the trial, defense attorneys were not allowed to call witnesses.

During a visit from French Foreign Minister Alain Juppe in October of last year, a Moroccan appeals court handed down harsher sentences for the convicted, upholding Othmani’s sentence and changing another convict’s sentence from life in prison to death.

Four days before the Marrakech bombing, tens of thousands of protestors marched in every major Moroccan city, demanding more jobs, less corruption, an independent judiciary, and a new constitution. In Casablanca, some 20,000 protestors, inspired by the upheavals of the Arab Spring and unappeased by earlier concessions from Mohammed VI, chanted, “We want a king who rules but does not govern.”

The crowd at Dar Tazi sat on the ground, cross-legged and hushed, eyes closed, waiting for a miracle.

Today, the February 20th Youth Movement is all but extinguished. Late last year, a protest organizer told the New York Times, “It is just too hard to keep going. They used so much violence against the protesters that people just stopped.” Disenchantment with the 2011 reforms has set in. In May, the Istiqlal withdrew from its ruling coalition with the Justice and Development Party, saying the party has failed to realize the gravity of the social and economic situation.

The night I went to the music festival, the Moroccan pop star Hatim Idar played to a crowd of 30,000 at Place Boujloud in the medina. Although Idar is a “TV singer” (he was discovered on Superstar, the pan-Arab version of American Idol), he is also considered a tarab singer. In the Arab musical tradition, tarab refers to a trance-like state of emotional ecstasy created by the interaction between singer and listener. It’s like a feedback loop—audience members give the singer energy by responding to the performance, which in turn induces a state of ecstasy in the singer that spills over to the audience. Most often, tarab conjures images of the whirling dervishes of Sufi liturgies, but it is not a religious concept per se. The idea is to achieve a higher emotional state through music, and Idar’s fans were after just that, helped along by dancing and kif-smoking.

Nearby, at Dar Tazi Palace gardens, a smaller audience was hoping for a quieter version of tarab. La Hadra Chefchaounia, an all-female Sufi ensemble, performed Sufi poetry set to slow, intertwining melodies accompanied by sparse hand drums. Such a performance is a rare thing to witness at all in Morocco; women’s Sufi ensembles don’t normally play public concerts, and the hushed, reverent mood at Dar Tazi stood in stark contrast to the raucous show at Boujloud.

The crowd at Dar Tazi sat on the ground, cross-legged and hushed, eyes closed, waiting for a miracle. I sat down, too. The singsong chants of La Hadra Chefchaounia drifted through the square, conjuring the promised re-enchantment of the world right there among us, under the stars and swaying trees. I closed my eyes to let it wash over me, to experience tarab and be re-enchanted. Within a minute, I was asleep.