The Procreant Urge

Ted Williams’s last game for the Red Sox was almost a flop. But it provided fuel for one of the best sports essays of all time—until the author started tinkering. On baseball, “The Simpsons,” and the creative impulse to never stop.

On an “overcast, chill, and uninspirational” day in late September 1960, John Updike watched Ted Williams play his last game for the Red Sox. Updike went to Boston that afternoon to have an affair, but the woman was a no-show. So as a fallback, he went with his alibi for the trip: He bought a ticket to Fenway.

His libido’s loss was literature’s gain. Less than a month later, the New Yorker ran “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.” It is, according to the New York Times, “Probably the most celebrated baseball essay ever.” But it’s a lot more than a “baseball essay.” It’s as good a piece of writing as you will ever find. Here are some highlights:

My personal memories of Williams begin when I was a boy in Pennsylvania, with two last-place teams in Philadelphia to keep me company. For me, “W’ms, lf” was a figment of the box scores who always seemed to be going 3-for-5. He radiated, from afar, the hard blue glow of high purpose.

And:

He struck the pose of Donatello’s David, the third-base bag being Goliath’s head.

And:

Whenever Williams appeared at the plate—pounding the dirt from his cleats, gouging a pit in the batter’s box with his left foot, wringing resin out of the bat handle with his vehement grip, switching the stick at the pitcher with an electric ferocity—it was like having a familiar Leonardo appear in a shuffle of Saturday Evening Post covers.

And with that I stay my hand from any more cutting ‘n’ pasting. You get the idea: Updike missed his tryst, but then the universe threw up a perfect alley-oop pass, and he slammed the rock home. (Pardon me if I resist a baseball metaphor.)

Famously, Ted Williams hit a home run at his last at-bat. He took the field in the ninth inning but the manager immediately replaced him. Williams sprinted back to the dugout—and with that, left baseball forever. It was not his team’s last game of the season, just their last home game before a final three-game series against the Yankees in New York. Here are the last three sentences of the essay:

On the car radio as I drove home I heard that Williams had decided not to accompany the team to New York. So he knew how to do even that, the hardest thing. Quit.

On April 30, 1992, the last episode of The Cosby Show aired. That same night, at that same time, The Simpsons was a rerun. You don’t compete with the venerable Bill Cosby on his last night if you’re a show not yet two and a half years old. Even if The Cosby Show had hung around too long, it was extremely popular in its prime. The programmers at Fox knew that tens of millions of Americans who no longer cared what happened to the Huxtables would tune in to see the finale.

Not me. I was 17 and a Simpsons fanatic. I’m 99% sure the episode that night was “Saturdays of Thunder,” where Bart is a soapbox derby racer and Homer attends the National Fatherhood Institute. There, he studies Bill Cosby’s book, Fatherhood, and, of course, masters it. Toward the end of the episode Homer holds up the book and says, “Bill Cosby, you just saved the Simpsons!”

After the credits—or maybe during them—there was a vignette not connected to the episode. As far as I know, it was never rebroadcast. Homer and Bart are watching TV. The dialogue goes something like this:

Bart: Hey, Dad, why did Mr. Cosby decide to end his show?

Homer: Because he didn’t want the show to stay around too long. He wanted to end it while it was still on top.

Bart: I don’t understand that. If I ever get my own TV show, I’m gonna run it into the ground.

Homer: Amen to that, boy. Amen to that.

The Cosby Show did not go out on top. The last few seasons were seldom funny and often preachy. Credited on his show as “Dr. William H. Cosby, Jr. Ed.D.,” the Cos could not resist trying to teach us a lesson.

The Simpsons won’t go out on top either. A few weeks ago, after one of those public squabbles over money common to both Hollywood and major league sports, Fox picked up the show for two more seasons—the 24th and 25th. Bart may get his wish.

Why is quitting the hardest thing? Because of:

Urge and urge and urge,

Always the procreant urge of the world.

We like to imagine our heroes always doing that hardest thing—walking away with their glory intact. We didn’t like it when, a few years after supposedly retiring with the Chicago Bulls, Michael Jordan donned a Washington Wizards jersey. It bothers us that The Godfather: Part III exists. R.E.M. broke up last month, but many fans will say they hung around a decade and a half too long. Willie Mays’s 22 seasons went from excellent to good to mediocre to “Oh, Willie…”

We should never be surprised when this happens. The fuel that drives people to greatness, what Walt Whitman so perfectly called “the procreant urge,” does not stop flowing when talent declines. For the greats, it never stops. “Song of Myself,” the poem where these lines appear, was first published in 1855. The version open next to me right now is the 1881 version. He revised it until he died. Urge and urge and urge: Whitman knew the feeling well.

In the last paragraph of “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” right after Williams’s home run, Updike quotes a Boston College student sitting near him:

One of the scholastics behind me said, “Let’s go. We’ve seen everything. I don’t want to spoil it.” This seemed a sound aesthetic decision.

We make that kind of decision all the time. The news of two more Simpsons seasons is irrelevant to most fans because we stopped watching long ago. It’s not suddenly terrible, but we’ve seen the glory days and don’t want to spoil it. Few of us watched Jordan score a mere 22.9 and then 20 points per game with the Wizards. We saw the 1998 Bulls and didn’t want to spoil it. And though we all got lured into seeing The Godfather III, it wasn’t a mistake anyone made twice.

That’s what makes Ted Williams’s last season so rare. He went out on top—or close to it. A home run in the last at bat to make 29 for the season. A respectable if, for him, modest .316 for the year. And with that final shot into the bullpen, he quit. “So he knew how to do even that…” You can see Updike behind the wheel on his drive home, shaking his head, saying those words aloud. Updike knew his American lit. He knew that urge and urge and urge is the driving force of athletes and artists alike. In fact, the procreant urge of the world drove him more than in any other writer of his generation.

The news of two more Simpsons seasons is irrelevant to most fans because we stopped watching long ago. It’s not suddenly terrible, but we’ve seen the glory days and don’t want to spoil it.

The Updike bibliography I am now looking at only goes up to 2002, and he died in 2009. So start with these numbers and then add one or two to each category: Seven books of poetry. Twenty novels. (I think he got up to around 23.) Fourteen short story collections. Seven collections of essays. One play, one memoir, and five children’s books. As of 2002, that is. He still had seven more productive years to go.

Updike is a prime example of “Nature without check with original energy.” (That’s Whitman again.) Many think he was too prolific, though I think that’s unfair, since on his worst day he could make a grocery list lyrical. Yet master though he was, even he could not do that hardest thing.

In 2010, the Library of America published “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu” in book form. Updike, just before he died, had added a preface, an afterword, and—wait for it—some excellent footnotes that reinforce observations he made in 1960 with statistics he did not have access to at the time. It’s even bound beautifully. However, the text itself is not the original New Yorker version. It’s an updated version he made in 1965 for his Assorted Prose. That version changes the ending—to my everlasting sorrow.

The closing lines from 1960:

So he knew how to do even that, the hardest thing. Quit.

Now read:

He had met the little death that awaits athletes. He had quit.

The entire point of the essay is that Williams is different—better than—every other baseball player ever. The 1960 version ends with him in absolute control, even of his exit. The whole essay drives toward that conclusion. The revised version ends with Williams much like every other athlete, meeting the “little death” of any old ball-player. This in spite of the fine .316 season, the 29 home runs, and the final at-bat. The whole point is that he did not hang around too long. The whole point is that he went out—as Homer Simpson said of Bill Cosby—on top! AGH!

This edit was not a sound aesthetic decision.

Urge and urge and urge. I don’t blame Updike for tinkering. I don’t blame the Simpsons staff for eking out more seasons. I’d do it too, probably. We all like to think that we too are the type, if the talent were ours, to sock one over the center fielder one last time and then skip the trip to New York. We like to think that we wouldn’t have made a third Godfather. We like to think that if The Simpsons were ours and ours alone, we would have spiked the football after the seventh season and headed to the locker room. But really, we wouldn’t. Most of us would spend 1881 revising, yet again, a masterpiece that we wrote in 1855, and most would spend part of 1965 and 2009 tinkering with an essay that we wrote perfectly well in 1960. Always the procreant urge of the world.

When I heard about The Simpsons’ contract renewal, I rushed to Twitter—where justice lives—to declaim: Thank God. Now they can continue watering down their legacy.

Yikes! Why the snide tone, self?

John Updike, in one of the many brilliant observations that make “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu” so much more than a baseball essay, had the answer: Greatness necessarily attracts debunkers.

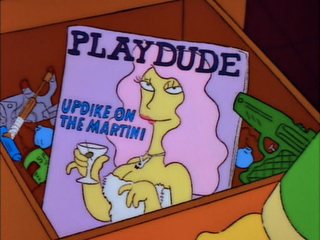

In an early Simpsons episode, Mrs. Krabappel confiscates Bart’s yo-yo and tosses it in her desk drawer with other confiscated stuff from students. Here is a picture of the drawer: