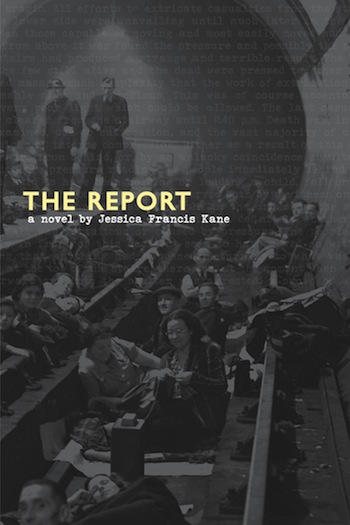

The Report

An excerpt of Jessica Francis Kane's forthcoming novel, The Report, about London's Bethnal Green disaster, where 173 people died in WWII's largest civilian accident.

The tragedy does not remain the story. Like any other public property, it is transformed by use. What you want is a loved one, child, friend, to be found, safe, alive. That’s not possible now.

A few days earlier you might have accepted an apology from the government, or an explanation of what happened, or a promise that it would never happen again. But none of these things came about, and now you want someone humiliated, forced to resign. You want someone to admit responsibility, someone held accountable. Desperate for these things, grief hot in your blood, you stand on a cold curb in front of the town hall, chanting with the others who are there every day, “The light, the light,” because to the crowd, the light is at the heart of the matter, the accident, the disaster, the catastrophe, whatever today’s papers are calling it, the event that ended the lives they had and gave them new ones they never wanted and never will. All their misery, all their unmitigated despair at what their lives have become, reduced to two words.

As the inquiry began, winter rallied. Temperatures sank, and the radiators in the room were not up to the task. That first morning, a crowd gathered and watched Laurence Dunne arrive by cab the way, he imagined, defeated villagers awaited their conquerors. They looked wary, but when Laurie stepped out and waved an arm in greeting, he needed the help of several constables to move through the sudden surge. They were not angry or violent, just insistent. Men called his name but were mute when he turned to listen. Women begged him not to forget the shelter orphans. They pulled back rough sleeves to show him their bruises, their children’s bruises.

Laurie strove to be warm and cordial yet noncommittal.

Inside the town hall he addressed Ross, the constable sent from the Bethnal Green police station to serve as messenger to the inquiry. “Our mission,” Laurie said, “is to create an encouraging atmosphere. Everything different from what Gowers started. An inquiry at the police station. Imagine.” He looked around the room he’d chosen for the proceedings. “A wobbly table shows we’re making do, just as they are.” He put a hand out and pressed the table’s edge. One of the legs clunked obligingly against the floor. “We want to be official in tone, helpful in mood. It’s a powerful combination. We will sit here and here.” Laurie pulled two wooden chairs forward and placed them on one side of the small table, angled as if for a fireside chat. “The witnesses will sit here.” He pulled a soft armchair forward from the front row and set it facing the table, close enough that the witnesses could put their feet up if they wanted to.

Laurie stared at Ross and waited a moment. He gave the impression of choosing a course from several available options. He had, as always, only one in mind. “Let’s go to the shelter,” he said.

They left the town hall and walked down Cambridge Heath Road. A low fog skirted the trees and buildings and seemed to make the sounds of a still-stunned community ring louder. Laurie was surprised by the amount of antirefugee graffiti he saw. Various statements about the manners and vices of “four-by-twos.” Crude opinions on “the Jewish problem.” It made him quiet, but Ross talked all the way there.

“The shelter entrance is parallel to the line of the street, sir, but the stairs leading down lie at an angle.”

Laurie would no doubt see that for himself. But the accident had occurred in a corner of Bethnal Green he didn’t know well, and so he was willing to listen. His life tended north, along the eastern end of Old Ford Road and toward Approach Road, which led into Victoria Park. Although their house was closer to St. John’s, he and Armorel had been attending St. James’s, off St. James’s Avenue, for years. Their butcher and green grocer lay north. And when Laurie went for a walk, he was more likely to head north to Victoria Park than south to Museum Gardens or the Bethnal Green Gardens, even though both were closer to him. He simply preferred the winding lanes and large lake of Victoria Park to the simple circle paths and paddling ponds that filled the parks of Bethnal Green.

“Hard to imagine such a thing happening next to the church, sir,” Ross was saying.

They arrived at the shelter, and Ross showed him the steps, pointed out how the first one, because of its relation to the pavement, was not of uniform width. “Could have been a contributing cause.”

Laurie looked at Ross with an expression calculated to impress upon him the value of circumspection. Then he glanced quickly at the wooden gates, the corrugated iron roof, relieved to find no graffiti. Still, the flimsiness of the structure depressed him. There were more of the hand-lettered signs, black ink streaked with rain, about collecting the victims’ belongings. In another hand, someone had written that tea and small sandwiches would be available.

Laurie was a religious man and an orderly one, and he believed in the necessity of war, but death like this at home? He knelt by the steps and pulled out his measuring tape.

Laurie and Ross descended to the landing at the turn in the steps to the booking hall. This was where the crush had occurred, and although the concrete had been scrubbed, there hung about the place a disturbing odor of urine mixed with damp and the smell of the garden above. Laurie quickly paced out the space and found it to be roughly fifteen feet by eleven. As he moved about, the gritty shuffle of his soles on the concrete bothered him. He found he could not escape an image of the fallen, interlocked bodies. He was a religious man and an orderly one, and he believed in the necessity of war, but death like this at home? He knelt by the steps and pulled out his measuring tape.

“Twelve inches, sir. Five and a half high.”

Laurie swiveled and looked up at Ross.

“I took the liberty of measuring the stairs this morning, sir.”

Laurie swiveled back. Plain concrete steps with a wooden insertion at the edge, he noted. Fairly even, though the wood dipped slightly below the level of the concrete. Ross’s numbers were exact. “Well done,” he said, standing, and Ross, embarrassed, shrugged.

Laurie pointed at the light socket above the steps.

“Empty,” said Ross.

“Obviously,” said Laurie.

“I mean, it’s a bit of a controversy, sir. It was always dim. Some wanted it brighter, others wanted it dark until a more protected entrance could be built. I’m not sure, sir. I’d have to reserve judgment on that.”

Laurie gave him a nod. “In general, a good idea.”

In half an hour they made a cursory review of the rest of the shelter. Laurie was impressed by the library, built on cement slabs over the tracks. A small mullioned window gave it the appearance of an 18th-century shop, right there underground. Beyond it was a recreation hall, and at the other end of the platform, a nursery painted with bright murals. It was all quite extraordinary. He’d had no idea. Farther on, Ross showed him a canteen selling hot soup, cocoa, sandwiches and cakes; two sick bays, one with a bathroom for delousing, the other with a rack of several dozen toothbrushes donated by the Junior Red Cross of America; and several nurses’ stations. The whitewashed tunnels were fresh and surprisingly bright, triple-tiered bunks lining the walls on either side as far as the eye could see. Well-posted signs gave polite directions and instructions to shelterers of all ages: You are requested to be in your bunk by 11 p.m. as the floodgate closes at that time. Laurie found himself nodding in approval. The underground life was better than he’d imagined, though when he looked at Ross, he saw him scowling.

“Very sad, sir,” Ross said, “if you remember why most people come here. Many have lost a home, and a family member or two with it.”

They walked back to the town hall in silence, Laurie watching the people on the streets, wondering which of them had been in the crowd that night. He thought how afraid they must have been, their passage to the shelter mysteriously impeded. But with that fear, there must have been annoyance, mounting to anger, fueled by exhaustion. He saw sleeplessness on every face.

Ross cleared his throat. “I wondered if I could be secretary to the inquiry, sir? Instead of messenger?”

Laurie pretended to consider a moment, then agreed.