This Was No Accident

Forty years after Jaws, why the very first blockbuster should be considered art—and how it helped one man to survive.

When he got back from the movies, my father’s face was uncharacteristically bright. Shaped by the sensibilities of his generation—Korea, John Wayne—he had always maintained a careful emotional blankness, the impassivity taken, at the time, to signify masculine strength. Every morning in the fall he would drive us to grade school without speaking, thirty minutes each direction, so that my brother John and I rode silently in the back seat, like taxi fares.

Yet today, this same man could hardly contain his excitement. It was that rarest of moments—I would later understand—in which the masks had all dropped away, and we were witnessing Da’s own inner child: the wonder-filled part that almost never emerged. Our family was vacationing at Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. I was nine.

“It’s a great movie,” he said, his voice made strange with enthusiasm. “Just great. I would definitely go again, if you guys really want to see it.” He hesitated, turning to consider us. “But it is scary.”

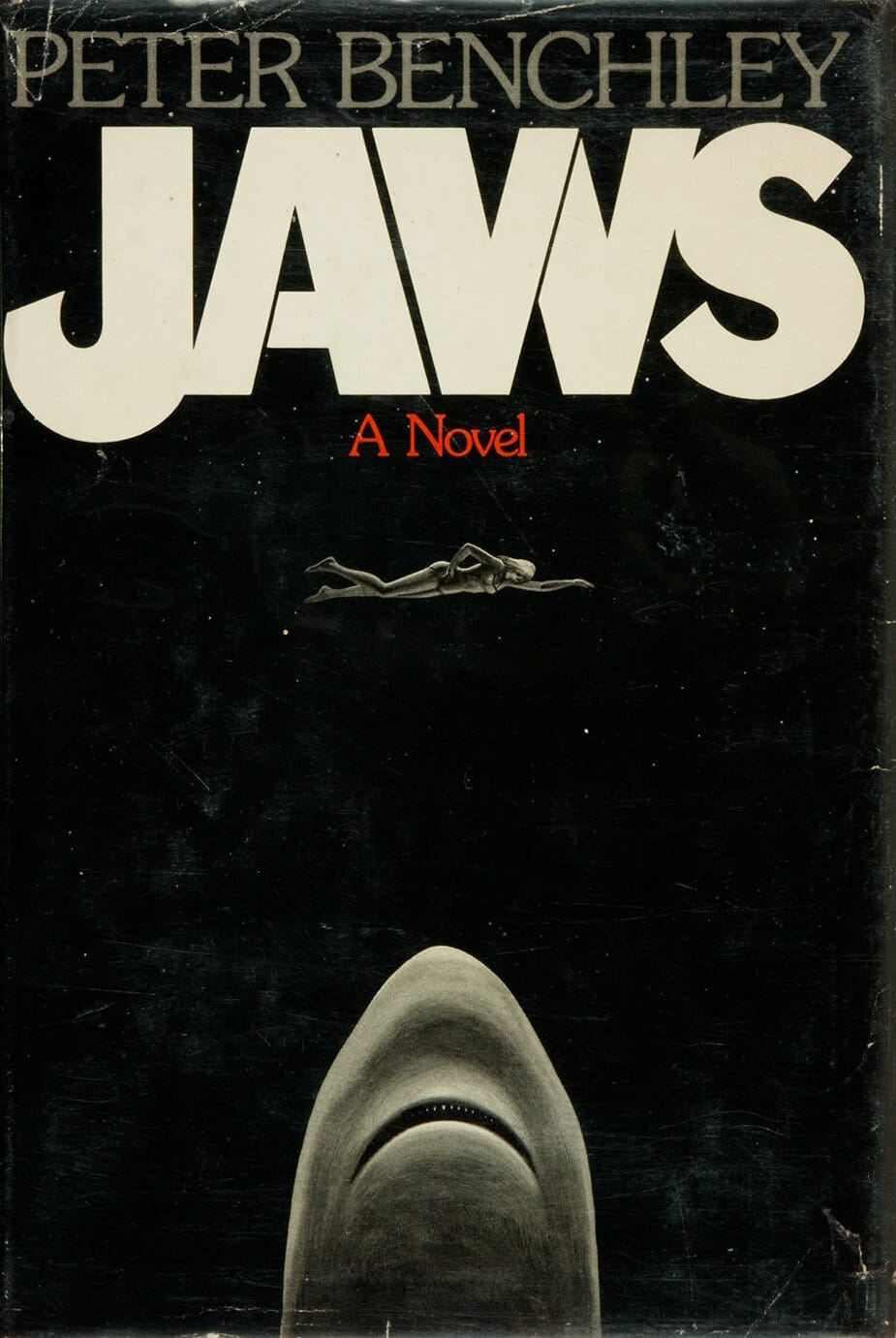

There we stood, the reason Da had made a solo foray to determine whether this film was all right for children: two shirtless boys in Day-Glo bathing suits, circa 1975. John and I had begged him to take us as soon as we saw the newspaper advertisements: that naked woman swimming in deep water, that rising, titanic mouth. There had even been an ominous TV commercial:

There is a creature alive today who has survived millions of years of evolution. It lives to kill. A mindless eating machine. It will attack and devour… anything. It is as if God created the Devil… and gave him…

“Yes,” Da said, his stern face remembering itself. “It’s pretty scary, men. Maybe we shouldn’t go.”

Da had a habit of calling us “men,” as if he were commanding a platoon of two very short recruits. “All right, men, I want to see you mowing the lawn.” “All right, men, let’s get those sleeping bags rolled.” He had served in the Air Force briefly during the battle for the 38th parallel, and favored military talk around the house.

“I said I would take you, if I thought you could handle it,” he conceded to our disappointment. “And I will. But I won’t lie. You might be afraid to swim in the ocean afterwards.”

These were unexpected terms. I looked at John’s face to see what was happening there. In his pupils was something I had never witnessed: My older brother was scared.

“I’ll go,” I said.

In the 40 years since that summer, I have often reflected on that decision. The moments from our childhoods that hurt us, that salt our faces with tears: These are easy to remember. The human system is so evolved as to recall pain and disappointment and loss in precise terms. Perhaps that’s what pain actually is—the formation of critical memories. But who can point to the moment of their most formative childhood joy?

I can. It was that afternoon my father took me, and me alone, to the movies. We would go to sea together, like men. Together, we would challenge the shark.

Jaws is a spectacular film, one of the greatest to come out of American cinema. It is rightly catalogued in the Library of Congress, where it has been preserved as a major cultural milestone. It also belongs in the very small club, alongside Herzog’s Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht and Friedkin’s The Exorcist, of “monster” pictures that are simultaneously true artistic achievements. After the movie opened, Steven Spielberg would become the household name he has remained ever since, but he would never again—forgive me for saying so of a billionaire with a shelf full of Oscars—make a film as seamless, and as dramatically accomplished, as this.

Spielberg’s most memorable images across the last four decades have been powerful indeed, but it is notable how often they hearken back to Jaws. On a light note, the kids trapped in the car as a T. Rex tries to bite them in Jurassic Park is essentially Matt Hooper inside the cage. (The director knows this: As the camera sweeps by, a careful look at the computer screens in the Jurassic Park control center reveals one of them to be playing Jaws.) On a heavier note, the bloodstained waves lapping gently ashore in the opening of Saving Private Ryan echo the same image in Jaws after the death of the little boy on the raft. There is also the moment at the climax of Ryan when our protagonist, with his last breath, repeatedly fires a gun at a tank—yes, it’s a visual pun—that suddenly explodes. What moviegoer in America doesn’t remember the exploding oxygen tank at the end of Jaws, shot through by Chief Brody as he hisses, Smile, you son of a bitch?

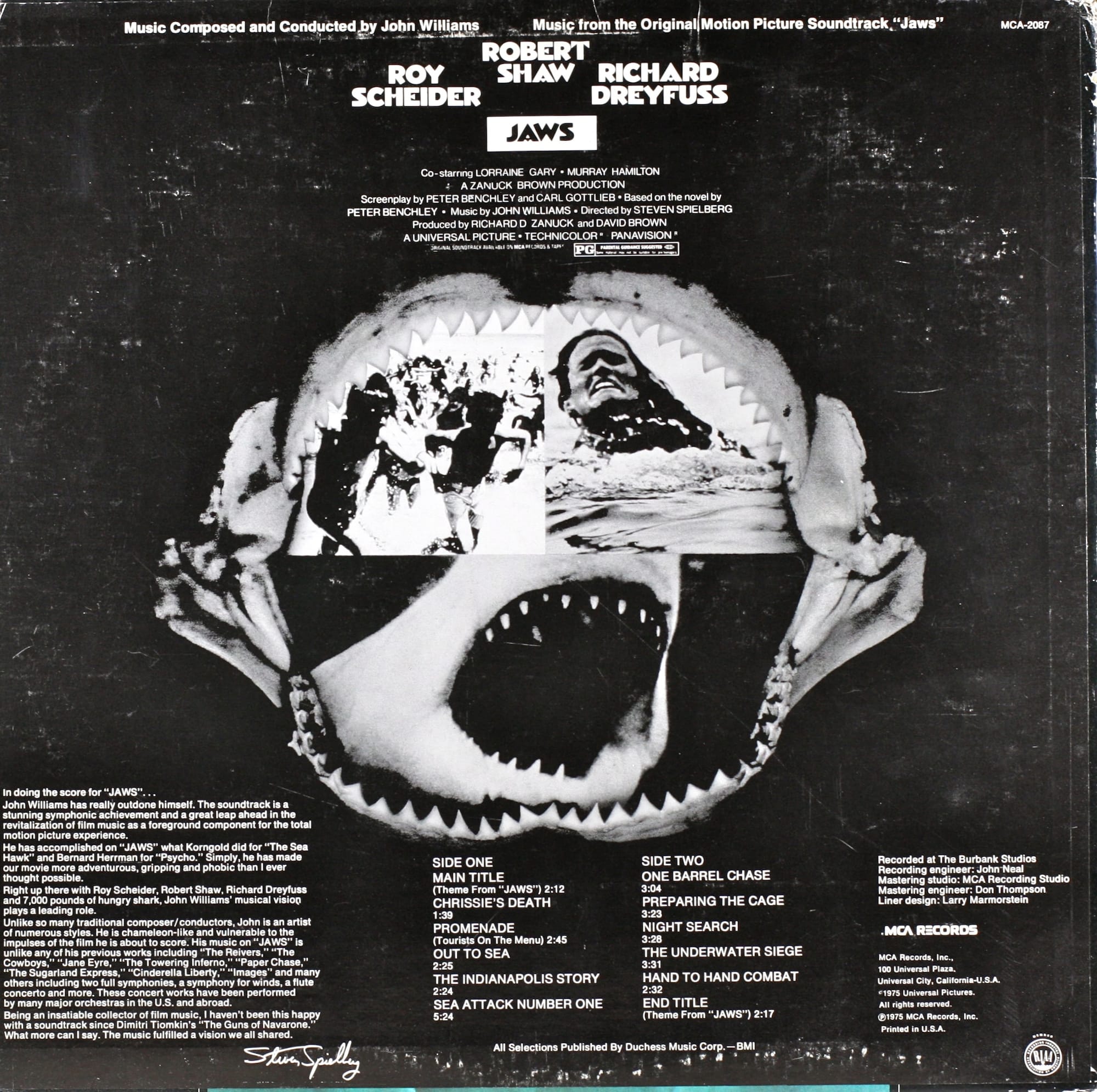

It’s commonplace to note that with Jaws, Spielberg created the summer blockbuster; without him, critics would no more be discussing this particular movie than the 40th anniversary of Death Wish. But the greatness of Jaws isn’t due to its wunderkind director alone, nor even to the “hook” provided by Benchley’s novel. The book, despite being a bestseller, is poorly written. The essential plotline is there: Landlubber Police Chief Martin Brody finds himself in over his head when a great white begins prowling the waters off Amity. As the body count rises, he struggles against the local authorities before finally going shark hunting with ichthyologist Matt Hooper and a foul-mouthed fisherman named Quint. Beyond this, though, the book is generally overstuffed (Mayor Vaughn is involved with the mafia?), the characters unlikeable (Hooper is having an affair with Brody’s wife?), the action occasionally tasteless (someone trying to pull an old man out of the surf accidentally yanks off his arm). This is hardly fail-proof source material. Credit for salvaging it goes, in large part, to screenwriter Carl Gottlieb, who picked up Benchley’s third attempt at a screenplay, streamlined the conflict, and forged a little American masterpiece.

The zeitgeist was right. 1970s America expressed itself neatly in Jaws, like a communal dream.

I spoke to Gottlieb once—more on this in a moment—and asked him how he transformed so unwieldy a source as Benchley’s book into something so lean as Spielberg’s film. “Concision begets significance,” he said—a line I now keep beside my desk.

Along with Gottlieb’s efforts, credit goes also to the three lead actors, each of whom shone brighter in this movie than in any of their more celebrated vehicles. Compare Robert Shaw in The Sting, Roy Scheider in The French Connection, and Richard Dreyfuss in The Goodbye Girl, and ask yourself whether those characters seem more real to you than Quint, Brody, and Hooper. It couldn’t happen again; had the shark hunter been played by Lee Marvin, as Spielberg wished, the film’s sensibility would quickly have become dated. Had the Chief of Police been played by Charlton Heston, as he wished, the result might well have been laughable. It’s a chance thing, this combination of talents.

But everything lined up just right for Jaws. Some of the movie’s best moments were wholly fortuitous—such as everyone’s favorite line, You’re gonna need a bigger boat, which Scheider improvised on the spot. Lovable fish-geek Hooper was supposed to die at the end, which would have been depressing, but was saved that fate when an actual great white became tangled in the stunt cage during underwater filming in Australia, leading to mind blowingly dramatic shots of the animal thrashing around an empty cage. There is a shooting star that crosses behind Chief Brody’s head during a moment of tense anticipation, producing a spectacular feel. Perhaps most famously, the fact that the enormous mechanical shark kept breaking down in salt water forced a delayed arrival time onscreen that immeasurably raises the intensity. And thank “the seven mad gods who rule the sea”—Stephen Crane’s phrase—that this film was shot before the advent of CGI; had that lamentable technology made its appearance a few decades earlier, the leaping shark would have hung mid-air in bullet time, every cartoony part of it pirouetting by 360 degrees before the camera zoomed down its gullet.

Finally, the zeitgeist was right. 1970s America expressed itself neatly in Jaws, like a communal dream. The movie theater lines around the block, the lifeguards rumored to be quitting their posts in droves, the Time cover proclaiming the arrival of “Super Shark”: All of it was part of a fish tale that grew quickly beyond record.

Spielberg is a big director, but Jaws was even bigger.

The movie begins almost before it begins. One of my favorite moments in the entire production occurs just prior to the first frame: Instead of fanfare over the Universal logo, we are given unexpected silence—and then, faintly within it, haunting underwater noises. Echoey, intimate and yet distant, this could be the sonar experience of dolphins, some hint of a vast world that both is and is not our own.

This is the sound, I would submit, of what Romantic poets called “the sublime.” We are moving into a territory much larger, and more alien, than the sunlit world in which we pass our daily lives. We are headed not just out to sea, but to Sea—that crucial difference that distinguishes a Conrad novel from one by Tom Clancy or Patrick O’Brian. In our current, cell phone-polluted theaters, such subtleties are often lost, but I have heard busily chatting audiences fall to stillness at this noise. Something deep inside us responds to that depth.

Amusing side note: The audio I am describing was actually produced, according to David Lewis Yewdall’s The Practical Art of Motion Picture Sound, by shrimp. Jim Troutman, who was the film’s supervising sound editor, recalls it as an accidental thing they noticed one day on their hydrophones. But it’s already there, in the first page of Benchley’s screen treatment: “HEAR a symphony of underwater sounds: landslide, metabolic sounds, the rare and secret noises that certain undersea species share with each other.”

And from this vast, undersea sublime, a two-note warning emerges.

Back on shore, our own senses are sharpened; there will be details to catch.

Open on a crowd of shaggy teens sitting ’round a beach fire, smoking, drinking, playing mournful harmonica. Anyone who was young in the ’70s remembers those floppy sweaters, those Styrofoam beer cups and the way a ring of sand clutched their bases. There is half-heard chatter about sex, about getting the keys to a boat, about somebody’s folks owning a condo in Maui. We aren’t supposed to pick up more than a general impression. But someone makes a louder comment, just before Chrissie runs off for a little night swimming—it’s the last bit of crowd noise we hear—that sounds like he’s an amputee. Listen again, if you own the DVD, and see if you don’t agree.

What is the subject matter of this background discussion? Plenty of young people sitting in movie theaters in ’75 had been to ’Nam, and plenty more knew someone who had. The draft had ended only three years prior. Many of these someones never returned, and some who did were missing arms and legs. This same decade would see the legless Steven Pushkov sing God Bless America at the end of The Deer Hunter (the lead was originally meant to go to Scheider); would see the one-legged Bradley in Sam Shepard’s Vietnam-infused Buried Child; would see the wheelchair-bound Luke Martin drive Captain Hyde to swim naked in the ocean at the end of Coming Home.

This innocent group of kids getting high on the beach, in other words, is already a threatened community. A violent force has been moving among them, picking them off at random, like a lottery. Midway through the movie, and on the Fourth of July, we will see a severed leg literally drop across the screen; later on, we will hear of soldiers left floating helplessly by their country while the fish circled. You know that was the time I was most frightened? Captain Quint will tell us, Waitin’ for my turn. We have entered upon unexpectedly political waters.

By coincidence, I had lunch recently with Dan Hull, who appears in the movie as the teenage boy who lifts a shrieking girl up on his shoulders, making us think she is being attacked. (His sister Stephanie appears as a little girl sitting on a raft and crying mommy, mommy; because she technically delivered a line, she has received thousands in royalties, while Dan got “something like 25 bucks.”) Our meeting was merely by happenstance. One of the interesting things about living in Boston is how frequently, simply by chance, one runs across people who were living on Martha’s Vineyard in the early ’70s and got bit parts as “local color.” Dan was over at my house because his daughter now goes to school where my wife works; a big, happy man, he regards his youthful involvement with Jaws in a whimsical light. I asked him how it felt to have appeared, even briefly, in a movie that has become a permanent cultural icon.

“It’s a neat little anecdote,” he agreed. But hardly as interesting, it seemed to him, as having been at Woodstock.

Dan didn’t go to the war, though he knew his draft number. By the time Jaws was being filmed, conscription had ended, and his own danger passed. But I wondered, as we spoke, about how many other young men who had sat in movie theaters that summer were well-versed in seeing their own turn come closer.

“And there are other readings,” notes the Deep Focus Review commentary on Jaws, including “the persistent theory of the shark as a sexual predator.”

That “persistent theory”—that there is a sexual subtext to all this fleshy business—is borne of the sense that if the film reflects its own historical moment, its most resonant imagery hints at something more fundamental.

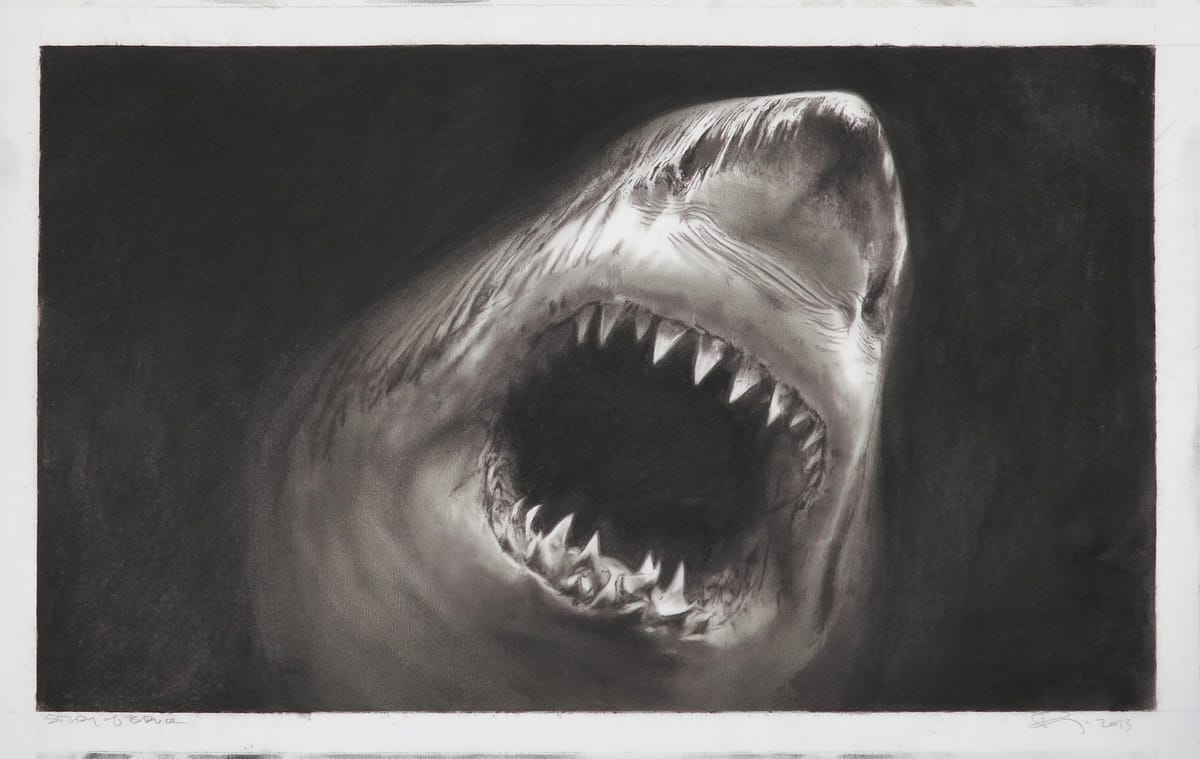

The original book cover is suggestive, and just possibly obscene, though in a dreamlike way. Its shark is certainly more phallic than the one on the movie poster that hung in my bedroom all through my teenage years. (One of Benchley’s original titles was “Leviathan Rising.”) The mere title itself struck an oddly salacious note at first, its subtext perhaps miscued by 1972’s Deep Throat—itself echoed in Jaws when two local yahoos look into a dead tiger shark’s mouth and one declares, got a deep throat, Pratt. When Spielberg himself saw the one-word header, according to some books on the director’s life, he wondered whether it referred to “a pornographic dentist.”

Karina Wilson, writing for LitReactor in 2012, comments on the uncomfortable fascination of that iconic shark-and-swimmer graphic:

From the “fish-hook” J of the title to the clearly naked Chrissie’s pert breasts to the outrageous proportions of the shark (if Chrissie gives us scale, that monster’s teeth are two feet long) to the disturbing psychosexual undertones (there’s a giant penis with teeth heading straight for Chrissie’s unprotected vagina! No, wait! It’s the giant vagina dentata that lurks in the deep sea of everyone’s subconscious birth memories!) it’s unforgettable. How could any reader not want to know what lies inside?

This kind of reading is not implausible with regard to the novel. There, infidelity looms large, forming the real menace faced by the castrated Chief. Hooper beds Ellen Brody behind his back; even Mayor Vaughn lusts after her. But film critics have adopted the “shark as junk” idea as well. I’m coming, I’m coming, Chrissie’s would-be partner whispers on the beach, just as she screams, it hurts. Back in ’75, Peter Biskind noted that, in the opening scene, “The shark, all too obviously, can only be the young man’s sexual passion, a greatly enlarged, marauding penis.”

As with most Freudian observations, there is something to all this, though it is unclear how much: The lone female, ready for sex, goes into the darkness. In the late 18th century, this story would have involved an Italian, a castle, some swooning. Is the beast ravaging Chrissie Watkins with its mouth an image of the one-night stand she was inviting on shore? Is the sexual desire hers or ours as we close in, to almost embarrassing proximity, on her privates? Biskind, for his part, took even the shrieking and cringing of her death scene to be “a diabolical parody of all those Hollywood bedroom scenes in which the camera registers celluloid ecstasy by discretely holding on a face, while the attached body is presumably tripping the light fantastic off camera.”

Amusing side note: comparison of the “Chrissie swimming” sequence with the “Kay swimming” sequence in Creature from the Black Lagoon, which wowed ’em in ’54 with its use of underwater photography, yields striking parallels. The general setup is familiar: A rickety yawl bearing scientists, a grizzled captain, and various phallic stand-ins (spear guns and toxin shooters were the thing) goes after a sea beast that turns the tables and begins hunting them instead. In fact, the influence of the Gill-Man—more obviously a metaphor for sexual desire, as he abducts the comely Julie Adams and transports her to his secret grotto for purposes better left implied—is overt. There’s a frustrated roar that can be heard at the end of Jaws as we watch the defeated shark dropping into the abyss. That sound clip appears at the end of Spielberg’s previous movie, Duel, but, film buffs have long argued, it is originally taken from Black Lagoon. And it’s hard not to compare the visual to Lagoon’s last shot: one of the defeated creature, once again—Freudians take note—sinking down.

In the autumn of ’76, my neighborhood friend Walter lost most of his leg to bone cancer. He had always been an undernourished boy, his nostrils reddish from frequent blowing, and was just shy of 13 when the tired-hurt feeling all around his kneecap refused to go away. I remember wondering why he didn’t want to shoot hoops in the street any more, why he was still asleep at 10 o’clock. Walter had no father; his mother was an unaccountably cruel woman, one of oddly many to be found in the outwardly successful milieu of DC lawyer-families. “That son of a bitch,” she whispered to me once, as if she and I might bond over her dying child’s complicity. “It’s his own fault for refusing to eat.”

A month later, Da drove John, me, and our mother silently to the Washington Hospital Center during visiting hours, and for the first time I saw what had become of my playmate. His previously flaxen hair had given way to nubbly scalp against his pillow, an aluminum pole replacing his left leg from the thigh down. Straight, long, it looked like the kind of attachment that connected to a vacuum cleaner. A pink plastic foot had been screwed onto the end.

I saw Lee Fierro speak in Oak Bluffs on the Vineyard. “No more slapping,” she said, to a tumult of laughing applause. “I am officially refusing to slap any more Jaws fans, ever again.”

“And in a child,” our mother sighed on the way home, to no one.

In a strange way, Wally’s missing leg made him a celebrity. Jaws was by no means over in ’76, or even in ’77, when Star Wars ratcheted down the intelligence of popular film and American culture began its decline toward the Reagan years. There was Jaws-inspired nonsense like Piranha and Orca and Tentacles; there were fly-by-night magazines on shark fishing, trumped-up accounts of tiger sharks that hunted in packs and the thresher shark that tail-walked across the sand to bite sunbathers. All boys had to learn new words like mako and blacktip and hammerhead. The worst long-term effect Jaws produced was a worldwide fear of sharks, which, unlike the monster in the movie, are beautiful and rare creatures whose numbers have been all but destroyed. That there remains a macho component to the killing of these fish is made clear by such yearly events as the Newport Monster Shark Tournament, held, until last year, on Martha’s Vineyard. In reality, global warming, overfishing, and the shameful Chinese market for shark fin soup (in the making of which sharks have their pectoral fins sliced off before being dumped, flailing and helpless, back in the water) has driven a third of all shark species to extinction’s edge. Peter Benchley, himself a sensitive ecologist, recognized the terrible energy his work had inspired, and spent the latter part of his career trying to bring public awareness to the desperate need to rescue sharks from us.

But this kind of enlightenment was still decades away. In the late ’70s, Walter’s disfigurement fit the narrative of the day. After he was able to stop wearing the wig, he and I used to sit together on Delaware beaches—from one side of his swim trunks a lanky, teenage leg; from the other, a stump—and wait for the inevitable question.

“Was it—was it—?”

“Shark,” Wally said sometimes, looking seriously into the eyes of the other amazed teens. Sometimes he even did it to grown men. “Hammerhead. Last summer. Right on this beach.”

Their faces seemed to say: I hadn’t actually believed it was real. Now, it was all coming home to them. The sharks were out there. Look what they had done.

The slap everyone remembers from Jaws is another of the movie’s strengths. Jaws is filled with those Martha’s Vineyard extras, but the marvelous Lee Fierro, who plays Alex Kintner’s mother, was a trained actress. She has long been associated with the Vineyard’s Island Theatre Workshop, where she remains active as a director, playwright, and teacher. When she hits Roy Scheider in the face for letting her boy die, we feel it—partly because, unable to fake-slap, she actually does it.

You knew there was a shark out there. You knew it was dangerous. But you let people go swimming anyway. You knew all those things. But still, my boy is dead now. And there’s nothing you can do about it.

The scene is perfectly set up to tell a complicated, but understandable, story of grief. Mrs. Kintner looks too old to be Alex’s mother. Perhaps she is an aunt, raising a sister’s child. Just a little too old, we think, maybe wincing away from our own judgment—certainly beyond having another child of her own. And what of the positively elderly man accompanying her? Is that her father? If so, where is her husband—is she a widow?

What we infer, in a flash, is that Alex had been Mrs. Kintner’s claim on youth. After him, nothing is left for her but sudden age. It will not be long before she wears the black veil again, by that old man’s grave: not long before her own, abandoned funeral. The loss of the child in the bloody surf has made her mortal as well.

I saw Lee Fierro speak to a crowd one night, a few years back, in Oak Bluffs on the Vineyard. She was in the Open Air Tabernacle, a graceful Methodist gathering space that had been rigged up not for a revival meeting but to show The Shark Is Still Working, a documentary on the long-term influence of Jaws. The crowd loved her, as I imagine they always have; some people have a natural stage presence. But she had a definite message for us that night. For over three decades, Jaws fans had been crossing over on the island ferry and asking her to slap them in the face. Frankly, she was done with it.

“No more slapping,” she said, to a tumult of laughing applause. “I am officially refusing to slap any more Jaws fans, ever again.”

“Hello?” the quiet voice asked, just last week.

“Lee Fierro?” I said hesitantly into the receiver. I explained that I was writing an article “on that big movie you starred in 40 years ago,” and wondered whether she had any comment.

“What would you like me to say?”

I’m talking to Mrs. Kintner, I thought, experiencing that weird double-consciousness produced by actors. Well, I asked, did it surprise her to see the film still going strong?

“No, not at all,” she said. “I was surprised up until the 10th anniversary, but not since then.”

“Mrs. Kintner” is now in her 80s, and I am a stranger, yet she was so warm-hearted and generous with her time that we both quickly dropped formality and just chatted. “Jaws—it’s not a part of my life,” she said, “but it changed my life, in many ways.” When I told her how this movie seemed to me to have many of the excellences more often associated with great art, she was not taken aback. “I agree with you. It is somewhat like the Greek dramas,” she said. “It may be partly because [Chief Brody] doesn’t know what he is facing. A lot of the time it’s Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss being hammered by the unknown. And we all fear the unknown, don’t we?”

She told me that during shooting, she wouldn’t agree to do the scene that made her famous unless she could remove all the dirty words—not out of prudishness, but because they were dramatically wrong. She said that Roy Scheider had refused to speak to her on set, but that, only a little while before he died, he had asked a mutual contact to apologize for him. He had needed to keep her a stranger in order to play the scene correctly, but had felt bad about it ever since.

“Oh, I won’t do it any more,” she repeated of the slap-happy fans. “Now I say, I’ll give you a kiss, but I won’t slap you.”

Before our conversation ended, Fierro had a question for me. Across four decades, she said, she had been receiving fan mail; people had always responded strongly to her performance. But those people were almost always young men. Why, she asked me, did I think that was?

I said I didn’t know. Perhaps it had something to do with men of my generation and our relationship to our mothers.

“Somehow,” she agreed, “it seems to speak to you.”

A quick article search on Jaws at the FIAC Index to Film Periodicals yields almost 400 hits (including “Pedal Pushers: Spielberg, De Sica, and Dismemberment”—“It is difficult to imagine two narrative features more different than Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist masterwork Bicycle Thieves (1945, Italy) and Steven Spielberg’s early blockbuster Jaws …”). Which leads to an interesting question: Is this movie low art or high?

The link to Moby-Dick is clear. In Benchley’s novel, Captain Quint is dragged to his doom in a tangle of harpoon lines, borne away by the whiteness that was his obsession. In fact, Spielberg had originally wanted to introduce the character of Quint by showing him in a movie theater, watching the 1956 Moby Dick and laughing uproariously. (Gregory Peck refused to allow the scene.) More subtly than this, in the opening sequence when we first meet Chief Brody, he passes through downtown Amity and underneath a sign that reads “Tashtego.” Tashtego is one of the Pequod’s harpoonists, a native of Gay Head, on the Vineyard; the sign belongs to a shop on Main Street, Edgartown. Yet it is also one of those delightful coincidences. By the film’s conclusion, Brody—whose burden is specifically that he was not born on the island—will be transformed into a Tashtego, desperately harpooning the Great White Thing from the mast of his own sinking ship.

Less immediately apparent is the link to Ibsen. Highbrow Jaws fans have suggested for a while that the first half of the movie is a retelling of Ibsen’s 1882 play An Enemy of the People, adapted by Arthur Miller in 1950, in which a lone protagonist comes to know that the local baths are contaminated (there’s something deadly in the water) but the moneyed powers-that-be don’t want him bruiting that information about. Amity is a summer town, after all, and they need summer dollars.

The connection to Ibsen is an odd one at first blush, and I always wanted to ask Carl Gottlieb whether it’s really there. But I hesitated to write him, though I had enjoyed The Jaws Log, his book on how the film came to be made. English professors—I had become one by my 30s—are often accused of egg headed over-reading. Perhaps, I thought, some day I might ask him quietly in person.

Chief Brody is not a superhero; he has none of the ridiculous musculature and bleached teeth of leading men today. He is afraid of so much.

My chance came in 2012. Back in 2005, the Martha’s Vineyard Chamber of Commerce held the first official JawsFest: a weekend-long gathering of “fin-addicts” and movie personnel, with talks by such luminaries as Jeffrey Kramer, who played the hangdog cop who finds an arm on the beach, and Joe Alves, who designed the mechanical sharks. Fans came in costume; fans wore fins; Susan Backlinie, who played Chrissie, strolled jauntily past me as I was trying to figure out the island map. Peter Benchley spoke, and the movie was shown on an outdoor screen. In 2012, there was a repeat, this time called JawsFest: The Tribute. Again the fans gathered, like pilot fish searching for scraps. Benchley had passed away in the interim, but his wife spoke for the family. Rodney Fox, a filmmaker and conservationist, was on hand, freezing the audience to their chairs as he described from personal experience what it feels like to be savaged by a great white. Rumor in the local bars was that Richard Dreyfuss might show this year, though he did not (perhaps he was still recovering from Piranha 3D). But the island is still home to many of the film’s secondary players—Jeffrey Voorhees, who played Alex Kintner, runs a restaurant there, and yes, it serves an “Alex Kintner burger.” The weekend’s highlight came with a moment that would have made Melville proud: a screening on the interior wall of the Old Whaling Church, with a mixed crowd of fans and actors sitting reverently in the pews. The experience was half cinema, half live theater, as every now and then a face appeared onscreen who happened to be present among the faithful, bringing a waving hand and a round of applause.

Gottlieb was on a panel the next day. Standing in line for the microphone during the question-and-answer period, I decided not to mention An Enemy of the People, the Tashtego sign, or any of the more outré interpretations. I just wanted to know whether he considered this screenplay to be high art.

“Well, people say that the first half of the movie is Ibsen,” he laughed.

“But is that a joke?” I pressed, relieved to know I wasn’t embarrassingly off-base. “Did canonical literature serve as your model in writing Jaws?”

He paused before giving his answer.

Sure it did, he said—An Enemy of the People, Moby-Dick, also Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. But, he cautioned all writers in the room, don’t get caught up too much in echoing other people’s works, no matter how deep they are.

“My main concern,” he said, “was telling this story, the best we could.”

In the film’s third act, the Orca passes into deep waters, and it is at this point that the journey becomes something mythical. There are hints before this, such as Chief Brody’s comment that sharks can live for thousands of years (false, but the suggestion turns our enemy into a primal force, something that swam the waters before Jesus walked on them). There is the fever-dream quality to the moment when the Bad Thing goes into the pond, where children are supposed to be safe. I know a woman who still says that cry—it’s in the pond, it’s in the pond—echoes in her mind with an elemental quality of dread.

But the moments of the most haunting beauty come out at sea. There is an image of the Orca in morning light that draws ahhhs from the crowd. There are those shooting stars that pass overhead, twice, seeming to signal our passage into the celestial. There is the lost cry of a humpback whale, heard in the desolated silence after Quint’s Indianapolis speech, as if nature itself were lamenting our fates.

I teach a course on playwriting now, and every year I show the Indianapolis speech when discussing the effective use of monologue. In retrospect, Robert Shaw should have gotten an academy award on its strength; not only is his delivery outstanding, but it colors all his own performances. Watch him in 1977’s The Deep, for example, to see an actor doing what appears to be an imitation of Robert Shaw. As with so much of the film, though, kudos for the Indianapolis monologue is spread out. Howard Sackler and John Milius lent an uncredited hand. But perhaps the most interesting fact is that Shaw, a playwright himself, took the script home and re-crafted Quint’s words on his own before delivering them:

Hooper: You were on the Indianapolis?

Brody: What happened?

Quint: Japanese submarine slammed two torpedoes into our side, Chief. We was comin’ back from the island of Tinian to Leyte—just delivered the bomb. The Hiroshima bomb. Eleven hundred men went into the water. Vessel went down in 12 minutes. Didn’t see the first shark for about a half an hour.

I went to graduate school in Bloomington, Ind., and once realized with a chill that the public monument whose plaque I was absently reading over was a memorial to the sailors of the USS Indianapolis. Their fate, the unbelievable torture of waiting one’s turn, is hard even to comprehend: hard—and here the word takes on its full meaning—to fathom. This is the real Deep: not merely the oceanic one, but the one into which Gilgamesh must swim in order to learn the riddle of how men die.

So, eleven hundred men went in the water, three hundred and sixteen men come out, the sharks took the rest, June the 29th, 1945. Anyway, we delivered the bomb.

How unbearably awful. How exquisitely told. It is as if, suffer as we must in our common humanity, we are things of whales and stars.

A few years ago I got my own cancer diagnosis. Unlike my childhood friend’s, mine waited until middle age, occurring in the back of my throat, just out of sight. There was no pain involved, no sense of anything amiss. By the time I noticed the strange thickness on one side of my neck, the neoplasm had already spread into my lymph glands.

Jaws had long since been a permanent feature in my life, a movie I referred to in times of both joy and need. I cannot say “everything I need to know I learned from Jaws”; I am a reader, and I have learned far more from King Lear and The Power and the Glory and The Secret Sharer. But the movie has been a steady companion piece. One day I met the love of my life, and soon we entered into a ritual of joy. Every Valentine’s Day I would take her to see Casablanca on the big screen; every July she would take me to Jaws. These became twin poles celebrating of the change of our seasons, and a recognition, I think, of how men and women see the world.

For me, the ultimate image of male heroism has always been a figure on a tilting mast, staring down a dragon. Chief Brody is not a superhero; he has none of the ridiculous musculature and bleached teeth of leading men today. He is afraid of so much. He is childishly afraid of the water. (There’s a clinical name for it—his wife tries, searching for a word. Drowning, Brody says.) He is cowed by the authorities in town. He hasn’t had time to fix the flue. He tries, time and again, to know what to do, against rapidly sinking odds.

That man, we ask? He is the one who must find it in himself to fight the monster? That frightened, outgunned, panicky man?

“Here’s what we’re going to do,” the surgical oncologist explained to me in the matter-of-fact manner of specialists. “It’s called a partial neck dissection. I’ll cut through here and here, being careful to avoid your carotid artery, and do my best to remove all of the tumor. Afterward, you’ll need to do daily radiation and chemotherapy for seven weeks. But first things first. Let’s get you scheduled for surgery.”

That man? I thought, holding tightly onto the arm of the chair in the consultation room. That frightened man?

There is a funny motivational poster I have seen that shows a picture of Chief Brody on his sinking mast, the enormous fin closing in fast. The caption reads:

PERSEVERENCE

Because You Might Not Get a Bigger Boat

Spielberg was, of course, right about the ending. In place of Benchley’s rather dull finale, he gives us the leap, the charge, the exploding tank. It’s pure Hollywood, and it works.

Afterward, as the audience cheers and the defeated Creature roars, comes an image of white birds. They are gulls, commonplace enough, but they flap and sail around our returning heroes in the film’s closing minutes like the beneficence of angels.

The tide’s with us, one of our two Ishmaels says—I never know whether it’s Brody or Hooper—and the reply comes: Keep kicking. If you were raised Irish, you recognize this sentiment as “Pray to God, but row toward shore.” Yes, we are blessed; yes, we succeed; yes, God loves us and hurries us gently toward home. But—keep kicking.

Every day for over a month I arrived at Mass General Hospital, had my face strapped down to a table with a hard plastic mask and radiation fired at my neck. Toxic chemicals were run directly into my veins. I wept a lot. To prevent myself from losing the ability to swallow—a risk among patients who endure head and neck radiation, during which everything inside your throat burns—I slammed my first against the dinner table, forcing down food I could no longer taste.

Eventually it hurt too much to speak, so my wife and I started texting each other while I was in a cab, or in a dressing room, or waiting to be taken in or out of machines. Sometimes I wrote the simple truth: Nausea bad this AM. Or, Docs say nightmares caused by meds. Sometimes, I was optimistic: Only three more weeks. As the date of completion closed in, I found it helped to text curses at the tumor.

Die, you damned cancer, I wrote.

Good, my wife texted back. Send me another. Let me hear you fight.

Get out of my body.

Yes.

Get out of my neck.

Good. More.

I am going to live. I am going to beat you.

And, on the last day of throat radiation, when that part of the long journey was done: Smile, you son of a bitch.

Suffering is indelible; a life lived is a life with scars. But who can point, 40 years gone, to the moment of their most formative childhood joy? For me, it was that day my father took me, and me alone, to the movies. This was the transition, the first moment of braving the adult world and everything it would bring.

The movie we experienced that night in 1975 was spectacular. Riveting, funny, exciting beyond belief. In it, I learned wonder—such as in the first time we see the entire shark glide past the Orca, the enormous span of its pectoral fins like wings. I learned friendship. I learned fate and how it works, the way men create their own mean and bitter ends. I learned heroism, the possibility of rising against one’s fears, and the white birds of hope and redemption and rebirth.

I have a deep scar, now, that runs from the back of my left ear midway down my trachea. My wife rubs the numb area where the nerve connections were cut, encouraging them to regrow: Come back, come back, she says, as if my nerves had wandered out to sea and needed a beacon to signal them home. Sometimes my writing students ask me about the scar. Remembering Walter, I look them carefully in the eyes.

“Great white,” I say, and watch their expressions widen. “I was diving off Key Largo. Didn’t see anything but this enormous mouth coming at me. Damn thing almost took off my head.”

Jaws is 40 years old this summer, and it endures. So do we all, the Tashtegos and Ahabs and lonely Ishmaels in the audience. I love my silent father, and I miss him. One night in 1975, he and I went out to sea together, to become men. We challenged the shark. And we won.