The poet Ted Kooser once said that flying in an airplane “is like being pushed from one place to another through a tight metal tube.”

Riding the subway, by extension, might be described as being ferried to your destination through a clanky pipe in the company of seven million coughing strangers. Mr. Kooser, a native of Iowa, may not have much experience on New York’s subways. I didn’t either before I moved here from the strip-mall-and-prairie shores of Lake Michigan. In any case, I might argue that riding under the weight of one of the world’s largest cities with millions of possibly, and perhaps likely, armed strangers is far more frightening than being flown through time in the crystalline air, with a ridership whose shoes are checked for weapons before boarding.

I have been riding the subways now for four years, a dust mote in time, but long enough to have seen some things: people vomiting into handbags, competing panhandlers, people who might have been copulating, live vermin, suspicious packages. But as New York has changed, so too have its subways; as our anxieties about life above ground have shifted, so they have below ground. It’s a chicken-and-egg scenario: Which came first, anxiety or the subway?

When the subways were first introduced, according to transit historian Joshua Freeman, “there was a fearfulness, but it was also very exciting.” Freeman’s grandfather claimed to have been among the first to ride the subway on its first day, Oct. 27, 1904, with 150,000 others. The cars were made of wood, and the track ran for nine miles, from City Hall to West 145th Street.

The system was built as a balm to the city above it. Writing in the Interborough Bulletin, A.L. Martin described the subway as being “hailed by all as the panacea of all the traffic ills harassing New York.” The city’s roads were in poor shape, and living space was in short supply, even though building was rampant. New Yorkers needed to be shuttled underground both to help connect the city’s neighborhoods and to get pedestrians and drivers out of the way of developers. Thus the subway was an innovation to be jazzed about: It was to bring about a new era of calm, safety, and efficiency for New Yorkers.

But the subway cars in their early days weren’t havens from the city above. As Clifton Hood writes in his definitive history of the subway, 722 Miles, stations were poorly ventilated, crowded, and dirty, due to “filthy masculine habits,” such as spitting and smoking. (The floors were “covered in gobs of spit,” Hood writes, even though the city tried to ban the habit to stop the spread of tuberculosis.) Subway seats were made of uncomfortable rattan, and bleak incandescent bulbs lighted the interiors. Demand was so high that passengers packed themselves into cars with hardly room to breathe. Sexual harassment reached such a boiling point that in 1909, it was decided that the last car in every train would be reserved for women. The suffragettes did not take well to this designation.

By the 1930s, however, the newness of the subway had given way to that old chestnut of human dread, isolation, and routine. The subway had become, like it or not, an organ of the city. The photographer Walker Evans hid a camera in his coat and surreptitiously photographed people on the train, a place where he said “people’s faces are in naked repose.” Indeed: His pictures show mostly white people, heads covered with scarves, hats, or veils, staring blankly ahead. It seems as if the passengers he captured are frozen in their own minds, impossible to penetrate even with a camera lens. The subway was not a new thing anymore, it was a New York thing, and New York things tend to be dirty and crass. It was a tool, according to Freeman, that most people used to go to and from work, “and people going to work, like today, tend to be, you know, tired and self-contained.”

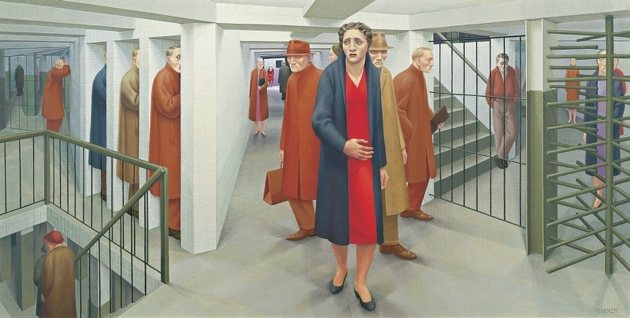

George Tooker’s 1950 painting “The Subway” depicts exactly that mood. A New York Times appraisal published after the artist’s death describes the painting as showing “harried figures” that “could be characters in a Greek tragedy, stalked by the Furies.” In Tooker’s obituary, the Times wrote that his works “expressed a 20th-century brand of anxiety of alienation.” Even upon close inspection, I cannot be sure if Tooker’s painting is of a subway station or a prison. But what’s most stirring is that, with just the addition of some iPhones, his painting could be of Union Square, today. Tooker’s pre-Benzo human forms, hiding in some Libeskindian landscape, the central woman’s gnarled hand larger than her skull, each draped in their earth-toned overcoats, are stolid forms of the misery of commuting. So much for the subway uniting the city.

By the 1930s, the newness of the subway had given way to that old chestnut of human dread, isolation, and routine.

By the 1970s, the city was falling into blight. Crime raged. The city was $150 million in debt. A 25-hour power blackout in the summer of 1977 produced so many arrests that there weren’t enough jail cells to hold everyone. Murder, robbery, and rape rates spiked. Photographer Camilo Jose Vergara started photographing the subways during this period. It was a time, Vergara said, when “the city was dying but the subways were alive.” His photos show cars tattooed with ink and etched with names. The passengers riding in them represent the actual demographics of the city, and, for the most part, those who entered the trains, paying 30 cents for a ride, held the strained fabric of the city in place.

In the 1980s, the city began an aggressive campaign to clean up the subways. By the mid-’90s, underground crime had fallen precipitously. Then 9/11 turned the landscape on its head. No longer was fear or dread confined to one place or another; it was everywhere.

After terrorism, two competing narratives emerged about anxiety and the subway. One, as terrorism scholar Juliette Kayyem told the Times, is that a terrorism attack on the subway is “terrorism as a form of urban warfare rather than as a symbolic gesture… It causes mass havoc, economic disruption or uncertainty and obviously casualties. But it also cuts to the core of what it means to live in an urban environment.”

But is that really what happens? We may not be so delicate. After the London subway was bombed in the summer of 2005, passengers returned to the trains the very next day. Sometimes the anxiety of a routine can actually be the most relaxing thing.

A co-worker, a native New Yorker, put it another way. “The notion of public space in New York is so distorted,” he said. “To be underground is a happy dislocation. The subway is like a library. It’s where I get all my reading done.”