War Plan Red

The quirky history behind the secret, full-scale invasion that the United States once planned for Canada, and vice versa.

O Canada! The dividing line between the United States and its great northern neighbor is often called “the friendliest border in the world.” Which goes to show how quickly people forget that, over the years, the two countries have wanted to invade each other over everything from dreams of Irish independence to a squabble over a single pig.

The Morning News spoke to Princeton Architectural Press publisher Kevin Lippert about War Plan Red: The United States’ Secret Plan to Invade Canada and Canada’s Secret Plan to Invade the United States, his new book chronicling the sometimes fraught and often ridiculous history of tension between the two nations.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The Morning News: I have to ask: how did you become interested in this topic? How did the history of US-Canada land disputes, which isn’t very well-known, come to your attention?

Kevin Lippert: I was having a conversation with one of [Princeton Architectural Press’s] Canadian distributors, a woman whose job is to sell our books in Canada, and she goes, “Are you working on anything that will be of interest to Canadians?’ I say, “I don’t know, what interests Canadians?” She says something like, “Canadians are very worried about what Americans are thinking of them.”

Then, two days later, I saw an article online where somebody had asked Obama if America had any plans to invade Canada and he laughed it off. But the article added that in the 1930s the United States did have a very detailed plan to invade Canada called “War Plan Red.” That information was shocking and there was something funny about the fact that that was shocking—like, when we think Canada, we don’t care enough to have a plan to invade them. We liked Iraq enough to invade them, but we don’t like Canada enough, it’s not as interesting.

So I dug into that history and it turns out that, like in many things, Canada was 10 years ahead of us and had developed their own plan to invade the United States in 1920. Now we’re such good neighbors and good friends, the idea seems kind of laughable. In fact, several people thought the book was a parody, that I had cooked the whole thing up and sort of forged these so-called authentic historic documents.

TMN: But the history is about more than just War Plan Red, which was in the 1930s, right? Your book discusses all these other times the US tried to invade Canada, such as during the War of 1812 which, it seems, did not go well.

Kevin: Yeah, there has been a long history of border conflicts between the US and Canada, which somehow nobody remembers. The War of 1812 was a major one, where we actually tried to invade. Either I didn’t pay attention in high school or we fast-forwarded past that war, which was a disastrous war for the United States in many regards anyway.

TMN: Why did the attempt fail so badly? Was it just arrogance at thinking that Canada would be easy to take over?

Kevin: It was a bit of arrogance, coupled with some incredible incompetence and some bad luck. Americans in 1812 really thought that conquering Canada would be, as Thomas Jefferson wrote, “a matter of marching.” I mean, we did have eight million people versus 500,000 Canadians, and our army was twice as large as theirs, and we had an increasingly powerful navy.

So I think Americans really thought it was just going to be a cakewalk. But, also, think about it this way. There’s one quote from somebody writing to President Madison saying something like, “Even the most pessimistic thinkers couldn’t imagine how undertrained and inexperienced our men are.” We were terrible soldiers and all our plans to invade Canada fell flat. People are shouting at each other in the dark, one guy rowed off with all the oars for the invasion boats—it was actually comical.

To be fair, some of it was weather-related and some of the troops were sick, but there were other larger factors as well. The war in general plunged the United States into terrible financial crisis—that was the first time the US defaulted—and so it had no money to pay its troops, and desertion was extremely high. I think 15 percent of the army deserted at one point, and there were a great number of executions as result of desertions. So morale was very low, and Canada, as it turns out, is very cold, so they were unhappy troops who weren’t getting paid in this incredibly unpopular war.

In a lot of these cases, there’s this recurring theme in which the US thinks they’re going to be welcomed as liberators. They invaded Canada during the Revolutionary War, for example, and thought the Québécois would join us in a fight against the British. We’ve heard this rhetoric in Iraq as well.

TMN: But such a bad failure didn’t seem to be the end of these attempts to, well, encroach upon Canada’s territory?

Kevin: After the War of 1812, there were some humorous border disputes. There’s the Pork and Beans War of territory between lumberjacks of Maine and lumberjacks of New Brunswick. Basically, lumberjacks on both sides couldn’t decide where Maine began and Canada ended, and vice versa, and kept sending volunteer militia to fight the others. It was named the Pork and Beans War because that was the lumberjacks’ favorite meal, allegedly.

There’s this pig war between the British and the Americans over the San Juan Islands off Washington State. This was in 1859. An American shot a pig in his garden, but the pig was owned by a man who managed a ranch that was owned by the British. They fought over the pig and its liability until it actually became a military standoff with cannons and warships.

The pig thing was silly. Even the British rear admiral, who was given the order to attack from the governor general of Vancouver, said, “For two great nations to go to battle over a pig is ridiculous.” He stood down, so, you know, at least one calm head prevailed. Same thing with the New Brunswick thing: the British said, essentially, the territory we are wrangling over is worth nothing. It was a big fight over a few trees. Though actually the US did gain some territory over the Pork and Beans skirmish.

TMN: There was a controversy over Lincoln’s assassination, too. People thought Canadians might be involved.

Kevin: So, John Wilkes Booth had been in Quebec not long before the assassination, and there was some speculation that maybe he got some money or maybe some arms up there. In Washington it was a serious conspiracy theory that somehow the Québécois had been tangentially involved in Lincoln’s assassination.

Another time we had the Fenians, Irish-Americans who wanted to invade Canada and swap it to Britain for the freedom of Ireland. It’s unsurprisingly an ill-fated story that didn’t work out so well.

On the one hand, Secretary of State William Seward was kind of tacitly giving his approval because he was courting Irish-American votes, and on the other hand we had a neutrality law. We were playing both sides of that. We were encouraging [the Fenians], but on the other hand arresting them as they scurried, then usually releasing them very quickly so they could mount another raid. They mounted five raids, including two of them with over a thousand men. But of course it wasn’t ultimately successful.

TMN: All of this is new to me, and, like you said, surprising. Why is it that we’re so surprised to hear about this part of history? I don’t know anyone bats an eye to hear about border disputes between the US and Mexico.

Kevin: Really, it’s because of how intertwined our two countries are. We are each other’s largest trading partner. There’s something like 60 million border crossings a year [39,254,000 trips by Canadians to the US in 2009; 20,213,500 trips by Americans to Canada in 2010—ed.], a million Canadians who live and work in the United States every day, and ditto the Americans who work in Canada. Our militaries are at this point all intents and purposes integrated. Canada has its own army, but it’s part of NORAD, which was expanded after 9/11 to include maritime matters, so we’re really joined at the hip at this point.

And that’s why it seemed so ludicrous now to think that both countries were thinking of it. Although in fairness it wasn’t exactly war between the US and Canada, it was between the US and Britain that would be fought on Canadian soil.

Americans in 1812 really thought that conquering Canada would be, as Thomas Jefferson wrote, “a matter of marching.”

TMN: Let’s talk about the actual War Plan Red. Why did the US end up drawing up the plan?

Kevin: The concern was that the United States and Britain would end up as enemies in a war, in part because Britain owed us a huge amount of money after WWI, and they were upset that we actually wanted to be repaid. Also they were not happy about the increasing power and presence of the United States on the world stage both in terms of trade and military. So even though we were allies and had been allies in WWI, there was some background tension there.

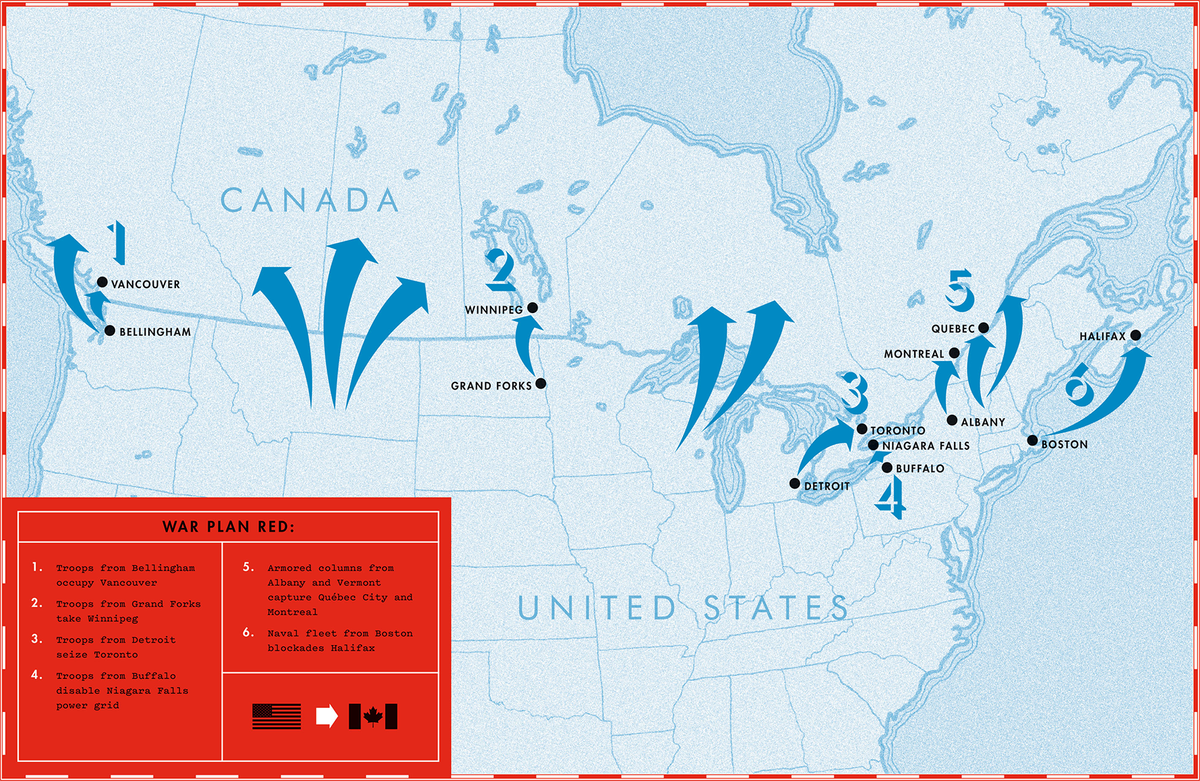

The war office and the Pentagon do what they did today: they needed contingency plans. So they drew up War Plan Red, which was the total elimination of what was designated as “red” on the map. The idea was really to put Britain out of the way once and for all. The United States figured that the UK could amass 12.5 million men in Canada in 40 days, so the United States needed to be able to fight that. The US thought it would be a war of long duration, so it would involve ships. The plan is very detailed, with every road accounted for.

TMN: What about the Canadian plan? Was it just as detailed?

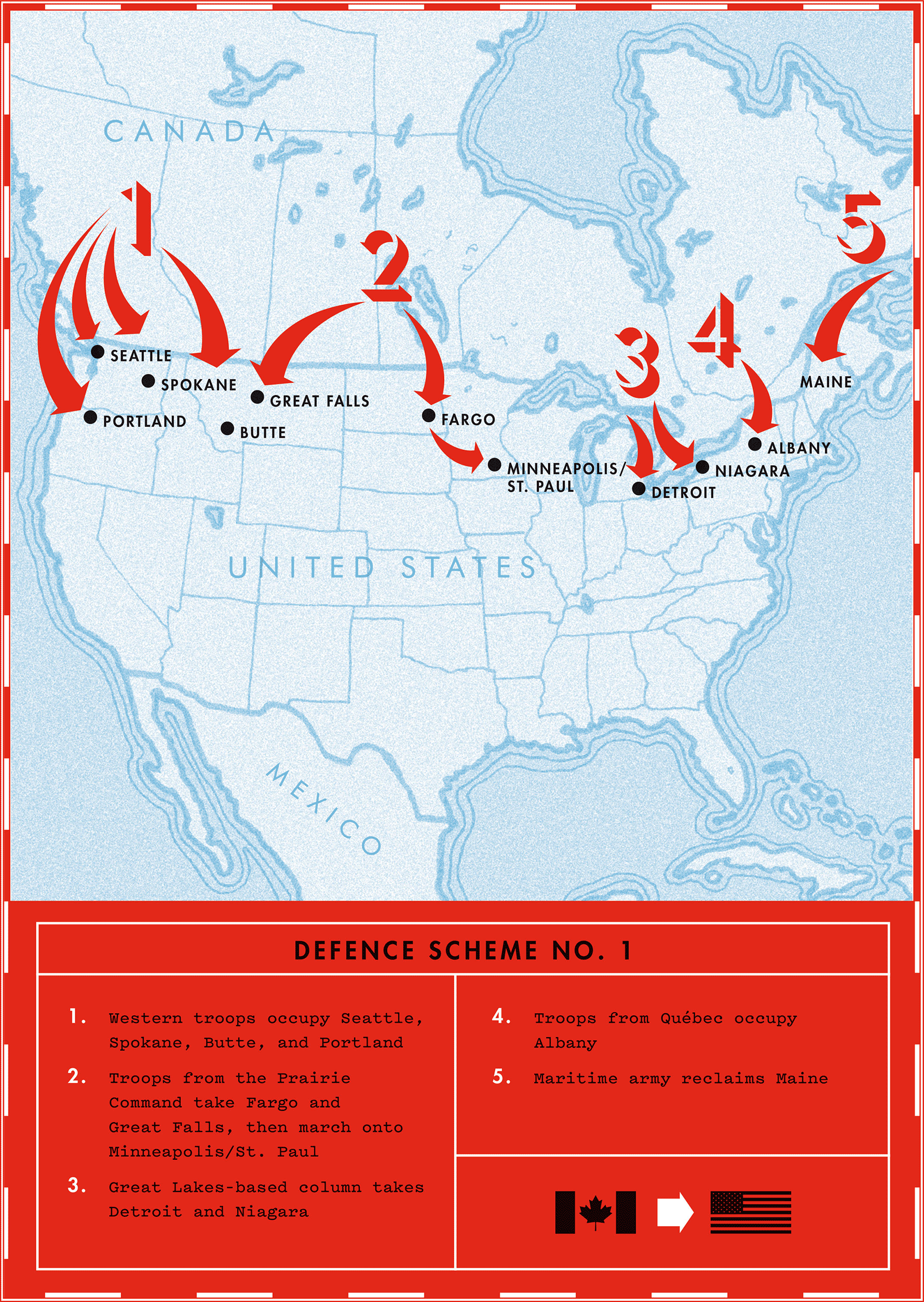

Kevin: The two plans were really kind of the same plan. I’d say that they’re almost mirror images, so maybe we each identified the soft spots along the border. But if you take the Canadian plan, which was drawn up first, and flip it over, it’s more or less the American plan.

The guy who drew it up was a WWI vet and he said it was an early version of the blitzkreig: you would invade quickly, throw the enemy off guard, and retreat blowing up bridges and roads, giving the British time to sail to the rescue of the Canadians.

The American plan was a bit the same: there would be flying columns that would attack the same cities. I’m not a military strategist but it’s interesting that the two plans are really the same, at least in terms of troop movements and overall strategy, which is that the best defense is a good offense.

TMN: I’m curious how much planning went into both plans and how likely it was that both countries thought they’d need to use them?

Kevin: Allegedly, the US plan was drawn up in two hours; I read this in my research but have no idea whether that’s true or not. The Canadian plan was a much longer process. The Canadians went on an espionage mission. They loaded into Model-Ts and grabbed Kodak brownie cameras and made notes. They went through Vermont and they made all these observations that are quite hilarious. Basically, that Vermonters are fat and lazy, they like to gossip and take a lot of breaks, and people in Burlington are more European than the rest.

The Canadians did this for many months, I think maybe as much as a year, but they also had a bigger hurdle and they were aware of that, so there was more planning. The US had kind of a hastily sketched-out plan but the US had at that point, again, thought it had the huge military advantage.

TMN: Why was the Canadian plan drawn out 10 years earlier?

Kevin: The Canadian plan was the brainchild of Buster Brown, who came back from WWI. He was suspicious of the United States, and he had also seen in Europe the horrors of what bad planning could mean. We know about the terrible conditions in WWI and he thought that Canada needed to be prepared for whatever the next war might be, and he just wanted to be prepared, so he was ahead of the game. I think he was just more forward-thinking.

TMN: When were the documents declassified? Are there any such border disputes today?

Kevin: The documents weren’t declassified until 1974, and the reaction even then was mostly that it was kind of funny. In terms of border disputes, in the late ‘60s the US sent an icebreaker called the USS Manhattan through the Northwest Passage, which was still one of those disputed areas between the US and Canada. Canada claimed it as territorial waters and US saw it as an international waterway. So that really upset the Canadians, and the United States basically said, “Well, we won’t do that again without notifying you first.” They didn’t say they wouldn’t do it again, just that next time there would be a warning. That was as close to coming to political blows as we’ve had in the past 50 years.

TMN: So nothing else since then?

Kevin: Well, there are some gray areas today. There’s Machias Seal Island, off the coast of Maine, which has a lighthouse, and it’s disputed whether it’s US or Canadian land. There’s still some dispute over the San Juan Islands and their borders, and these interesting bits of US soil surrounded entirely by Canadian land, which is just the result of the whole history of crummy border designation.

For example, there’s Province Point in Lake Champlain, which is part of Vermont but surrounded by Canadian land. There’s Elm Point and there’s Point Roberts out in Washington state, which is a little spit of land that, supposedly, has many people in the federal witness protection program because to get there you have to go through two international borders—so I suppose it’s a safe place to staff people. It’s also very popular for Canadians to come and shop, get cheaper gas and groceries. Actually, the well ran dry on Point Roberts in the early 2000s, and there was a “Canadians Go Home” demonstration among the Americans.

So there are still these little moments of friction even today, though I’d hardly call them border disputes. Today, I think, it’s all really good-natured.