White Rabbit

When illness erases the fine line between love and obsession.

“It’s terrible here at night,” Sesha said. She was sitting across the table from me in the psychiatric ward at Forbes Regional Hospital, dressed in a T-shirt and sweatpants, her makeup washed away. We were alone in the day room, late November sunlight casting long rectangles across the white tile floor. Behind us was a darkened television set mounted on a metal support arm that reached out from the wall; puzzles and board games were stacked high on a nearby shelf.

It was Thanksgiving 1992. I was 15 years old and in the 10th grade. Sesha was 14. Out in the hallway dinners were being delivered to patients, prepackaged meals of turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes, and cranberry sauce shrink-wrapped on plastic trays filed neatly in a stainless steel cart. A male orderly in scrubs lumbered down the corridor wheeling the cart from room to room, the unmistakable scent of hospital food strong in the air. Sesha still didn’t have much of an appetite, so we sat and talked while most of the other patients ate quietly in their rooms.

“What do you mean by terrible?” I asked, worried.

“That guy at the desk? Scott? He hits on all the girls here,” she said. “But he waits until late at night. He’s a pervert.” The ponytail in her hair had come loose, so she undid the elastic band holding it in place and, for a moment, her auburn-colored hair fell to her shoulders.

“He thinks he’s attractive or something, it’s weird,” Sesha said, pulling her hair tight again in a new ponytail.

“Has he hit on you?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, as if I was foolish for asking. “But don’t worry, it’s not like I’m going to sleep with him.”

The thought hadn’t even entered my mind. At least, not until she planted it there. It was a practice she had mastered in the three months since our first kiss, sowing seeds of doubt at any opportunity. But even though I was aware of the way she sometimes tried to manipulate a situation, the line between fantasy and reality somehow remained impossibly hard to distinguish.

Though Sesha and I had only been together since late August, we had known each other for more than a year. We met in ninth-grade art class, a general curriculum course taught by a woman who was rumored to have been a Playboy centerfold in the 1960s. Sesha flirted with me from that first class, touching my arm when we talked and whispering to me between the lessons taught by the teacher. We both shared a similar sense of humor, dry and sarcastic, and easily fell in together. That she was smart and attractive only helped to magnify my self-consciousness each time we talked.

From the moment we met she exuded a confidence I had never seen in someone before, a confidence that would later evolve into a strange power over me.

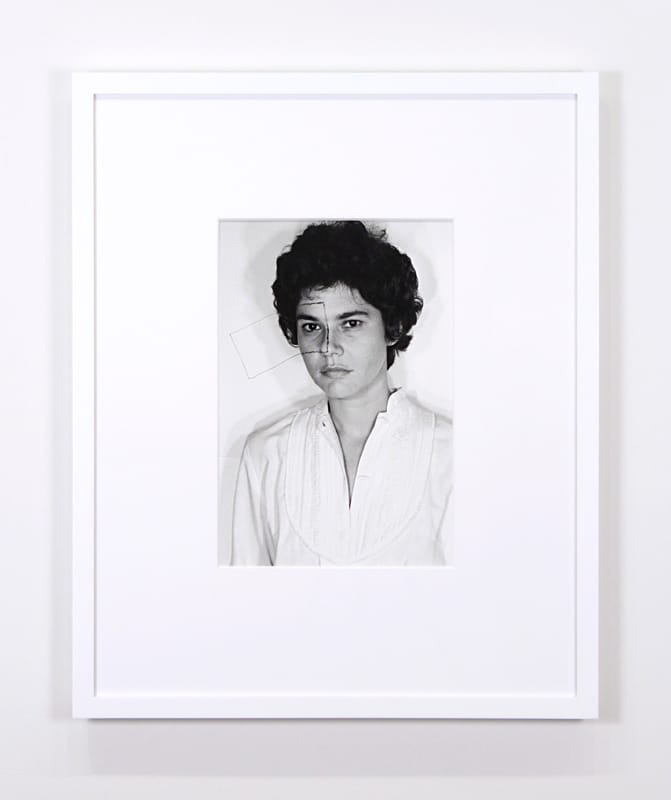

Sesha was from a multiracial family, part white and part Indian. Her dark hair fell to her shoulders and she often gathered it together and pulled it to one side of her neck while she worked in class—usually the side opposite of where I sat—exposing her full profile so I could see her lips and neckline, the curve of her jaw and the silver hoops in her pierced ears. From the moment we met she exuded a confidence I had never seen in someone before, a confidence that would later evolve into a strange power over me.

I couldn’t tell if Sesha was lying or telling the truth about Scott, who was a middle-aged man with dark, close-cropped hair and wire-rimmed glasses. His particular role on the ward was unclear, but he seemed to be an administrator, someone perhaps with a background in therapy who had taken on the role of managing staff. My only interaction with him was when I signed in at the front desk each time I visited. He had been pleasant in our limited encounters. Was he capable of making sexual advances toward a teenage girl?

“Tell me what I should do,” I said. “I can help.” My mother, who was reading a book in the waiting room outside the ward, had been doing her best to advocate for Sesha. I figured if any of this were true, maybe she could help. What worried me, of course, was Sesha’s tendency to exaggerate. She often placed herself at the center of drama, whether real or imagined. It was an aspect of her personality that I never quite understood considering her real life was chaotic enough on its own. Six days earlier that chaos is what pushed her to the psychiatric ward at Forbes—a move, it turned out, that was less the signal of an unsettled mind and more a measure to keep her father at a safe distance.

“I can’t go home tonight,” Sesha said. “He’ll kill me.” She was referring to her father, a strict Indian man whose temper and authority loomed like a monolith over her family’s household. We were in my bedroom at my parent’s house when she said this. It was the Friday before Thanksgiving and Sesha had ridden home with me on the bus after school. Her deep-brown eyes welled with tears as she talked, mascara running in inky-black dots against the olive-colored skin of her cheeks. In her right hand was a copy of her report card. She had received two D-grades for the semester: one in science, the other in physical education. She cut each class regularly, often to meet me under a quiet stairwell we had found in one of the school’s back hallways, where we would fool around or just daydream about the future; other times to smoke pot on the hiking trail behind the school with some of the stoners that she knew.

To Sesha’s father, failing grades were unacceptable. It didn’t fit with his image of his daughter or the distinct idea he had for what her future should look like. The way she explained, her father expected she would graduate at the top of her class, go on to a respected four-year university, somewhere like Case Western Reserve, and then consider her options for graduate school. While the details got murkier after that, there was often talk, however serious or not, of an arranged marriage with a young man from another Indian family. It was a daunting vision. But the fact that her father had no idea of what was actually going on in her life—and what he might do if he found out—seemed to scare her the most.

“I don’t know how to explain this to him,” Sesha said, holding up her report card. Her voice was fragile, breaking apart a little at the end of each word. She was sitting on the blue carpet in my bedroom, her knees tucked tight to her chest with her back against the closet door. A miniature Chicago Bulls basketball hoop that was a gift from my parents when I was in junior high school hung several feet above her head at the top of the door.

It was strange to see Sesha so upset. The only time she ever showed signs of fear was when talk of her father came up. Though he worked long hours as a nuclear physicist at a nearby research facility, his presence in her life was pervasive. Even though pleasing him was not necessarily what she wanted to do, it was an obligation that colored many of her decisions. Given his own accomplished career, Sesha’s father expected academic excellence from each of his four children—three daughters and a son—and his discipline often turned physical when disappointed with them.

A year earlier, before we were dating but when we spent hours on the phone after school each day, Sesha told me that her father once pushed Abeer, her younger brother, down a flight of stairs in their house. The fall was violent and left her brother, who was in grade school at the time, with a broken arm. Sesha couldn’t remember what it was that set her father off, but that was the point. His reactions were as unpredictable as his temper.

Since I had never once met or even seen Sesha’s father except in photographs, a certain kind of mystery surrounded him. The framed pictures in her house revealed a short, dark-skinned man with tinted glasses and a crown of thinning black hair. It was intentional of course that we had never met. He forbade any of his three daughters from having a boyfriend. Sesha’s mother, however, a pleasant but timid American woman, was far more lenient. Unlike her husband, she was well aware that each of her three daughters secretly had boyfriends. When I would visit Sesha after school, her mother was particularly nice to me. She would make us food and tell bad jokes while we sat around the kitchen table. I would play video games with Abeer or help her mother carry in groceries from the trunk of her Pontiac LeMans parked out in the driveway. It all felt extremely normal. But there was always the knowledge that the fun was temporary, a welcome but finite lull before Sesha’s father returned home.

“I’m afraid what I might do if I go home tonight,” Sesha said, wiping away tears as she looked up at me from the bedroom floor, her eyes now searching, it seemed, for some sort of reaction.

“What’s that mean?” I asked, hearing a familiar sense of frustration in my voice. I wanted Sesha to be clear about what she was hinting at, to just come out and say it.

“You really don’t know?” she asked, sounding irritated. “Never mind then.”

I also questioned how serious she was, knowing the pleasure she took in making a situation unravel. The last thing I wanted was to further agitate her. But I also didn’t want to play along.

I knew she was threatening suicide, or at least to do some type of harm to herself if she had to go home and face her father. But I also questioned how serious she was, knowing the pleasure she took in making a situation unravel. The last thing I wanted was to further agitate her. But I also didn’t want to play along. I had done it in the past. Not with threats of suicide, but with other issues just as serious.

Earlier that year Sesha had told me that a varsity soccer player raped her at a party when she was a freshman. Her account of what the boy had done was matter of fact, almost emotionless, and caught me by surprise. To learn someone had done this to her set me in a rage. The next day I confronted the boy in the hallway at school. I asked him, bluntly, what happened at that party and a fight broke out. Teachers quickly intervened and separated us. As we were each dragged to the principal’s office the boy laughed at me for believing Sesha’s story, told me I was an idiot for being so gullible. At the time I ignored him. I was in the right, I assumed, because why would Sesha lie about such an awful experience. But as the months wore on I had more and more reason to question the stories she told, and the reasons for telling them. So many of our conversations were like falling down a rabbit hole; the truth so obscured it often felt impossible to set any of it right in my head.

I sat down on the floor in my bedroom next to Sesha and held her hand in mine. The house was warm but her fingers felt cold.

“You don’t know him,” she said about her father, her voice soft again. She reminded me that it was impossible for me to know how he would react. She was right.

Out in the kitchen, my grandmother was checking on a pot roast she had put in the oven several hours earlier. The smell of seasoned meat and roasted potatoes reminded me of when she used to cook for my sister and I when we were little, before I had problems that couldn’t be solved.

I looked at Sesha. She wasn’t crying anymore but her eyes were red, the skin above and below her lashes tender at the edges. Before I could say anything, she interrupted.

“I’m not going home,” she said. “I’ll kill myself if I do.”

When I pressed her about Scott, Sesha downplayed his behavior.

“It’s probably just playful flirting,” she said. “You shouldn’t worry.” She told me this as we walked laps around the outer edges of the ward, watching the clock as 8 p.m. approached and visiting hours came to a close.

“You would tell me if you needed me to do something, right?” I asked as we stopped outside her hospital room.

“I’m fine,” she said, softening a bit. “It’s OK here.”

We said goodbye for the night. I kissed her and we hugged for what felt like several minutes. After all that she had told me when I first arrived, I was still afraid to leave. But I couldn’t stay any longer either. A voice boomed from the small circular speakers in the ceiling: Visiting hours are over for the evening. Please remember to sign out at the front desk and wait for a staff member to buzz you out.

I signed the log, scrawling my signature next to the date and time of my visit. On my way out of the ward I looked over my shoulder and saw Scott standing there motionless, his eyes fixed on the exit.

I wanted to hug my mother but I didn’t. The space between us felt too heavy.

Out in the waiting room I found my mother sitting on a couch near a bank of vending machines. All the other chairs and small couches were empty; rows of florescent tube lights hummed loudly overhead. She looked tired but smiled when she saw me.

“How is she?” my mother asked, tucking the paperback that she had been reading into her purse.

“OK, I guess,” I said, rubbing my eyes, which felt heavy and dry. It was hard to hide how tired I felt. My mother’s face fell a little when she noticed. It was more a look of pity than anything else. The last few days had been like trying to sleep through a fever. I felt uncomfortable when I was with Sesha, and out of place around my parents, like I was living in an alternate reality. I wanted to hug my mother but I didn’t. The space between us felt too heavy.

“She’s in a better mood than yesterday,” I added, keeping Sesha’s story about Scott to myself. “Still not eating much though.”

“Hospital food is the pits,” my mother said, smiling a bit. “Don’t worry, she’s gonna bounce back.”

I was grateful for my mother’s support, but I could tell what a struggle it was for her to stay positive. Outside of my relationship with Sesha, the last year had been difficult for our family. Since freshman year of high school, my mood and state of mind had started to shift. I spent more time by myself; I slept long hours and was impossible to wake in the mornings; and I was regularly acting out of character—a change most noticeably marked by fits of anger and near-constant irritability with everyone around me. The most dramatic changes, however, were a series of compulsive and increasingly odd behaviors. I had taken to constantly checking door locks, excessively washing my hands, counting every footstep that I took, and had even developed an overwhelming concern that each time I spoke I might offend someone. It was maddening.

My erratic behavior and the weight of my new habits had my parents concerned. So after months of resisting, I had finally agreed to an evaluation at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. The night Sesha was committed to the psych ward at Forbes was just two weeks before my evaluation, where I would be formally diagnosed with severe clinical depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. It proved that my parent’s fears were not unfounded. Something was wrong with me.

“This is more than you can fix,” my mother said, referring to Sesha’s problems with her father. “The best you can do is to be there for her, be a good listener.”

It was Thanksgiving night. We were seated at the lunch counter in a Denny’s set amidst the suburban sprawl near the hospital, finishing our dinners. On my mother’s plate was a hot turkey sandwich, half eaten and skinned-over in cold gravy. Crumbs from a BLT dotted my plate, the inedible crusts neatly discarded in a semicircle. On the counter was our receipt, set down by the waitress in the wet ring left by my water glass. I picked up the soggy piece of paper and handed it to my mother, who looked at my hands, which were dry and irritated from too much washing.

“Dad can take you to the hospital tomorrow, if you want,” she said as we stood up and walked to the cash register. She was rifling through her purse as she talked, searching for her wallet.

I wondered what version of Sesha I might see the next day. Would she be rational and kind, like she was in the final minutes before we had said goodbye tonight? Or would she be spiteful, talking in half-truths that left my brain in knots?

I would learn much later that my parents, particularly my mother, had deep concerns about Sesha’s influence on me. In the notes from my initial evaluation at Western Psychiatric, the clinician wrote: “Matt’s mother reports that he may speak to his girlfriend on the phone 6-7 times per night, and she is concerned that he feels responsible for her psychological well-being. Mrs. Newton also stated the concern that somehow Matt’s girlfriend would push him into a joint suicide.”

My mother smiled as she handed the bill and her credit card to the man behind the cash register.

“Was everything OK tonight?” he asked, a pleasant look on his face.

“Yes,” my mother said. “Everything was fine.”