Rodeo Days and Nights

From Texas rodeos to New York City streets, black and white photographs find modern life endlessly surprising.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: Let’s start with the rodeo pictures, which is how I first learned about your work. The New Yorker sent you to photograph young bull riders. Did you know you had something special on your hands when you entered that world?

Jonno Rattman: When you’re on assignment, there is a certain rush of responsibility that distinguishes it from working for yourself. There are probably no second chances, there is a weight to the work. To prepare, of course, you charge batteries and make sure you have backups and backups for your backups.

I can’t help but pre-visualize what I might see. Sometimes I make a shot list, but that usually goes out the window as soon as I show up. You can never really be sure of what will happen or what you’ll see—that’s part of the thrill. You’re given license to go see for yourself. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, all rights reserved, copyright © the artist.

Interview continued

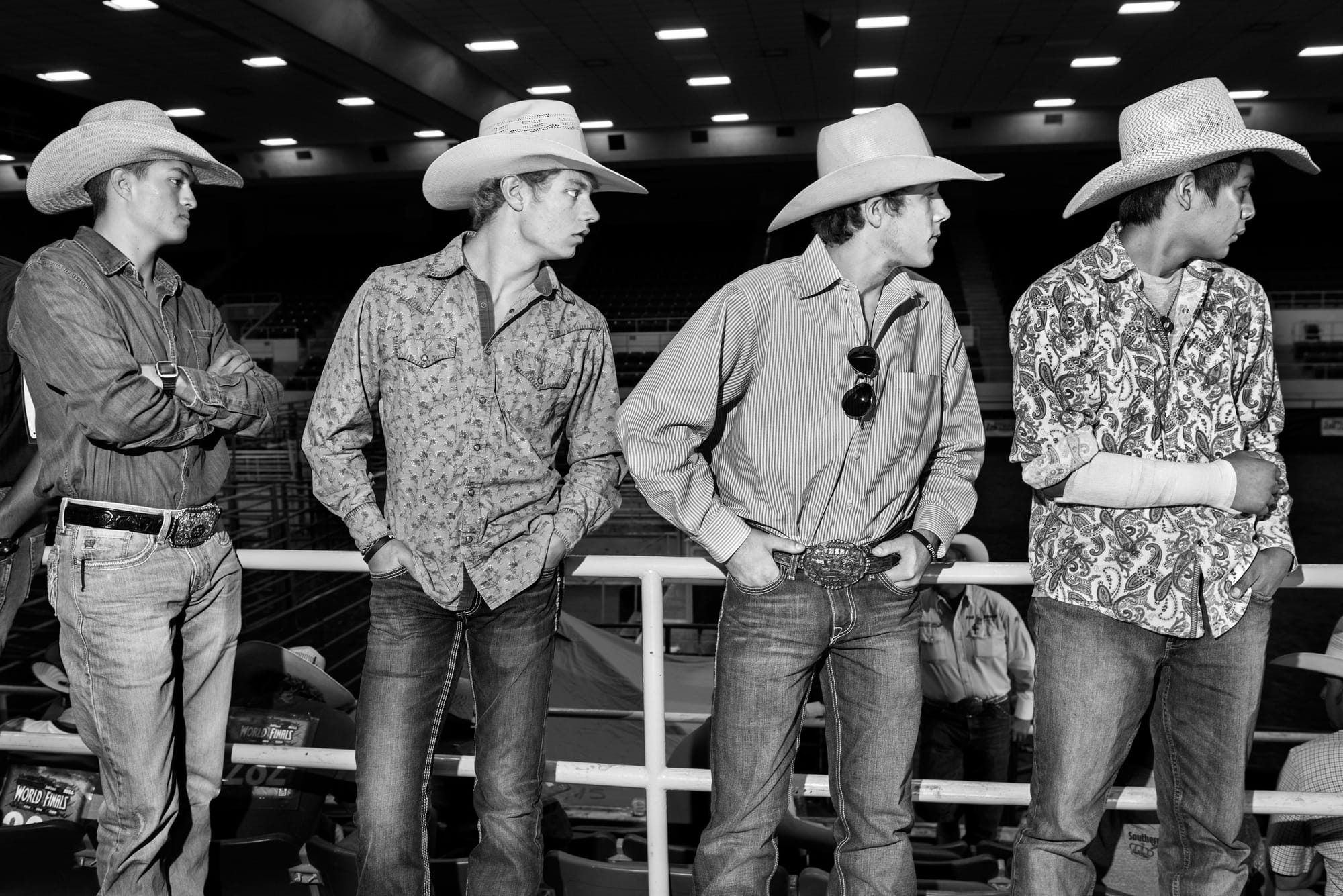

When I got the call to go to Texas, I was thrilled. My editor rang me and asked, “Are you free on these dates? Yes? Fantastic! How would you like to photograph kids riding sheep and calves and bulls in Abilene, Texas?” Now, just imagine getting a call like that; there was instantly a delicious stew of pictures and ideas in my head. There would be a few main subjects whose portraits I should make, but otherwise I was told, “go, do your thing.” That’s the dream.

After my first day at the rodeo, I was still covered in dust and sweat while talking to my parents on the phone. I remember saying, “I can’t believe I’m being paid to have this much fun.” If I can keep this going for another 60 years, I’ll be a frail old guy having a hoot at the tricentennial celebrations in Washington, DC. I might be one of the only people already planning for the 300th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

TMN: Earlier, there was the series “He Walked by Night,” shooting New York after dark. How did that start?

JR: In the fall of 2010, I was just starting my sophomore year at NYU, and I couldn’t wait to do work that mattered. I felt stuck in college. I was impatient and hungry. I had just finished up a semester with all A’s, writing and reading and photographing voraciously. And here I was, with the days getting shorter and colder, in a couple courses I chose by mistake; I was reading critical theory for a class on the directors Krzysztof Kieślowski and Andrei Tarkovsky. It should have been an amazing; those directors are incredible. Instead it was clinical, cold, over-academicized nonsense. All of this, in the midst of the financial and housing crises, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the first disappointing years of President Obama’s term… People everywhere were suffering, with real stories that could be told in an effort to make change. I was completely immersed in the news, disaffected with school, and perceptive to a feeling of growing societal insensitivity to other human beings.

At the time, I lived on Thompson Street between Bleecker and Houston, five flights up to a 56-square-foot bedroom. I felt caged-in. I was so worried and anxious about everything that I was turning into an insomniac. I just couldn’t sleep. So I began to take late-night walks as a sort of therapy, and I always carried my camera. I’d leave my apartment at 11 p.m. or midnight and walk around my neighborhood, or sometimes down to the financial district, until 2, 3 or 4 a.m. I was in a pretty dark mood, but my neighborhood was something to see, especially at night. Bars and clubs and late-night restaurants line those blocks, and there was always a party, both inside and out. I started making pictures of the people and situations I saw. Pretty soon, it was clear that there was something to the pictures. I dropped three classes and did an independent study with my photography adviser, Editha Messina, and a history of photography course with Shelley Rice. Every week, I would bring enlarged contact sheets and prints of the photos I made the previous week or even previous night. I was using film, but I would either process the film in my apartment or on my lunch break, after loading film into canisters with a dark bag, while in Shelley’s class. I worked on this project from October to December out of necessity, not because I was trying to do street photography or anything else—it was a way for me to figure things out. Thankfully, it was also productive.

TMN: Did you see yourself as a street photographer at that time? Do you now?

JR: All the labels in photography are pretty unproductive. What is a fine art photograph? At what point does documentary become art? Can street photography be done inside? It’s probably more revealing to look at pictures for what they are and how they fit into a lineage or into ideas about what a picture is or can be. The trends and terms of acceptability are constantly shifting in photography and have been since its inception. Photography, 50 years ago, was struggling to be considered art, and it would have been unthinkable that a print by a living artist could fetch multiple millions of dollars.

TMN: You work as a printer in addition to being a photographer. How much does the printer influence the working artist when you’re out shooting?

JR: Photography and printing now are made up of 256 tones. If you’re working in color it’s three or four channels of 256. The arrangement of tones tell you everything you need to know about the emotional and spatial articulation of a given instant. Pictures happen in real time, in a flow, and yet the images we see are still, solitary, removed from that flow. The job of the photographer, to some extent, is to anticipate—to intuit—what pieces of the flow are worth holding on to for what they might reveal about the experience of being there, making photographs.

A picture is a result of consummate subjective experience drawing on past and present observation, simultaneously. For it to be a “good picture” it probably needs to forge an internal rhythm—a dynamic, interesting, emotional space bearing empathy and conveying a point of view—and all this while working within a set of technical conventions or constraints. Some of the conventions arise from the history of photography or journalistic ethics, and some of the constraints are physical, spatial, or camera-dependent. So I work within this set of rules and I do everything possible to get the pictures right, in-camera. I’ve learned certain ways of working to make pictures look and feel like my pictures; and that’s also an essential part of printing. Is there a consistency of spirit and vision across a body of work?

Working as a printer has taught me many things, not least of which is how valuable it is to get things right the first time, not only for the sake of time, but also for the immediate believability of pictures that haven’t been tampered with. I’ve also learned incredible lessons from every project I’ve printed for another artist. You can’t spend six months or a year working side-by-side with a gifted, articulate human being without learning a hell-of-a-lot about everything.

TMN: You work mostly in black and white. Who do you admire for color?

JR: When it comes to color, I hold several photographers in high-regard: Helen Levitt, Saul Leiter, Larry Sultan, early Steven Shore and William Eggleston. In terms of photographers working in color more recently, I have great respect for Alec Soth and Philip-Lorca diCorcia.

I do like color, but it’s a very difficult to execute a nuanced palette. Color tends to be either too contrast-y or too “dirty,” but when color is clean or crisp, it often looks like fashion work—which is not to diss fashion, but to draw on a set of associations or references. Color pictures tend to work best when the color composition adds to the whole intrinsic meaning of the photograph. John Szarkowski got it right when he wrote that much color photography “might be described as black-and-white photographs made with color film, in which the problem of color is solved by inattention.” The great color photographers are able to wrap a moment in color, form, and narrative quality, simultaneously. They see it all.

TMN: What’s overrated in photography right now?

JR: I’m tired of cool detachment and unemotional distance. I’m tired of the banal for the sake of the banal. I’m tired of assemblage still-lives on bright-colored backdrops. I’m tired of pictures of people taking pictures. I’m tired of selfies. I’m tired of sentimentality and tropes. I’m tired of trends. I’m tired of navel-gazing. Too much meta is boring. Show me something amazing!

TMN: When you look in the eyes of people you photograph, what traits do you see most frequently?

JR: Listen, you, me, everyone is in their own world, and yet we cohabit this planet. I firmly believe in the goodness of all people until proven otherwise. If I’m making a portrait, I try to connect on the deepest possible level with who they are in relation to who I am, and how we feel about each other. It’s a visual handshake. Just as a handshake can give you a hint as to who someone is or their sense of themselves, so can a portrait. It takes two to tango, but you must always introduce chance. In reportage, you’re working with more candid moments, where there’s a split-instant recognition of the potential for revelation and narrative coinciding with a shutter click.

TMN: So what type of subject are you repeatedly drawn to?

JR: Many subjects have potential, especially if you go in fresh, wide-eyed, and irreverent. I find that I like to work with groups of people, regardless of the circumstance; I could be at a sporting event, a demonstration, a busy street corner, a party, a music show, a performance, whatever. Something where people are getting on and doing their thing—that’s what I like to see. There’s a lot to learn from those interactions. Everyone has a different way of catalyzing their existence and there are hints to it everywhere. The trick is making it into a picture that doesn’t just show, but tells.

TMN: You’re only a couple years out of school, and you’re already getting assignments from the New Yorker and the New York Times Magazine. Besides your own talent and hard work, what do you credit for your rise?

JR: I’m incredibly fortunate. I got my first call from the New York Times Magazine when I was headed out the door on the morning of graduation. I had just finished a big project—working on reproductions for a book on John Cage—and the next day the phone rang. It was inexplicable and wonderful.

I try to make it easy on my editors—they have a ton on their plates—and I try to do my best to make a pile of good, narrative pictures no matter the story. I have a lot of fun doing what I do, and I’m sure it shows.

TMN: What’s your dream assignment?

JR: It’s hard to put a name on a dream assignment—every assignment keeps the dream going. I would love to do another story like the rodeo. Not necessarily a sporting event, but something quirky and wild with plenty of freedom.

TMN: Sometimes the work we like the least takes the most effort, and the stuff that’s best comes about smoothly. Is that the case for you?

JR: Of course! That’s why, to the greatest extent possible, you have to do what you love. The best career advice my brother ever gave to me is “Don’t have a backup plan” and I think my mentor Yo Cuomo invokes the corollary on a couple of great hand-made posters in her studio—one says “Either for Love or for Money, there Ain’t No In-Between,” another says “Never Slit Your Wrists for a Lunatic.” If you can stick to those guidelines, make a little luck and commit to a lot of hard work you might be okay.