-

March 25, 2022

Semifinals

-

Katie Kitamura

2Intimacies

v.

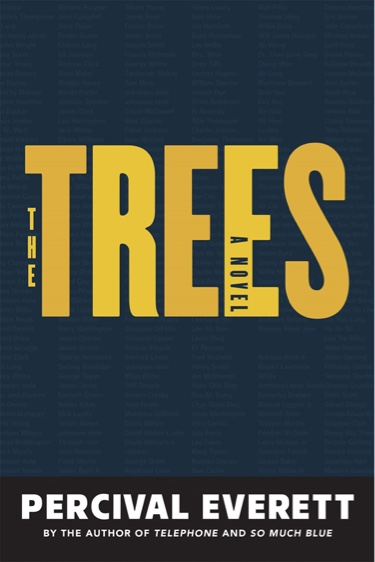

2The TreesPercival Everett

-

Judged by

Crystal Hana Kim

2022 began with an omen dream that woke me in the night. In my family, dreams are portents, so I called my aunt right away. There had been blood all over her, I said, so sure it meant disaster. But blood can mean goodness, fortune, she insisted. I felt unmoored, off-kilter. I was away from home teaching in Virginia, and what was I supposed to trust, my dream or the meaning of the dream? The next day, my partner and baby got Covid, upending all our plans. On the impromptu plane back home, I kept wondering: So this is how it’s going to be, 2022?

This is all to say that we’re barely into this new year and I already feel a million years old. Around me, loved ones have shared stupendously good news as well as sadness, death. We are living through our third year of the pandemic, and it feels relentless. What I need from fiction is a story so engrossing I can fall away from myself, my dreams, our strange and circumscribed lives. Both The Trees by Percival Everett and Intimacies by Katie Kitamura accomplished this in such drastically different ways.

I’ll start with The Trees, which begins in Money, Miss., with a murder. A dead white man’s body, castrated, is found next to a dead Black man who resembles Emmett Till. This dead Black man is holding the white man’s balls. What the hell is going on? That’s what everyone in the book and I, the reader, wanted to know. But what happens when that Black man’s body disappears? When another white man is murdered in a similar circumstance, and then another, with this dead Black man’s corpse reappearing and redisappearing? Is this a ghost story or something worse? The Trees is a wild, unexpected, propulsive, rageful journey of a book.

Reading it felt like looking at the cover—at first glance, I saw a black background, the words THE TREES in an ugly shade of yellow, but as I returned to it after the explosive first chapter, I noticed columns of names in dark gray: Trayvon Martin. Kendrec McDade. Yuen Chin Sing. Jennie Steers. Unknown male. 16 adult men. Anthony Lamar White. Murdered victims of police violence and hate crimes and lynchings, their names all over the cover in plain sight, if only you take care to look. Like the cover, this book asks you to consider deeply, to look again and again. It surprises you with its horror and gravity, with the overlap between history and the ongoing killings of Americans, predominantly Black and male.

And yet The Trees is funny too, so darkly humorous it feels illicit. How does Everett so effectively write about rage and a racial genocide, of revenge and retribution, while also making us laugh? The novel is full of quick quips (in one scene, Jim and Ed, the two Black cops from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigations complain about the Wi-Fi in their motel: “‘What did you expect from a Motel 8?’ Ed asks. ‘I don’t know. Two better than a Motel 6?” Jim responds.’”), slapstick and near-absurdist jokes, deft wordplay, and zany names (one man belonging to the KKK is called Reverend Doctor Fondle).

Everett uses dark humor to unbalance the reader, but the true focus never sways. This is a social satire that begins with one question, which births many: Has Emmett Till returned from the dead to avenge his wrongful death? There’s the fear and hope of a mystical answer, but the core is always a real-live pulsing heat, a rightful anger at our country and its willful hiding of racism and massacre. As Mama Z, the local witch and root doctor (and perhaps the oldest citizen of Money) says, “If you want to know a place, you talk to its history.” The Trees was so different from what I usually read, more gruesome and satirical—and this is why I loved it so much.

Now, I’ll admit that I devoured Intimacies last year, astounded by its ingenuity, so it had a slight edge going into this competition. As I reread this slim novel after The Trees, all that I loved came back to me. An unnamed woman works at the Hague as an interpreter, and as she parses through her complicity in translating for a man accused of war crimes, there are layers of intimacy in her own life she must navigate, too—her lover Adriaan abruptly leaves to see his ex-wife, her friend Jana unwittingly introduces her to a woman whose brother has been the victim of a brutal attack, the lawyer Kees who once hit on her is now a colleague at the Hague. A simmering question lies at the root of this book: Who is telling the truth and is there a singular truth?

Bright and warm, the covers of these Memo Books are heavily debossed with graphic patterns based on flowers that are among the very first to appear each spring, and then stamped with three luscious, reflective foils. The dot-graph insides are made from a superb paper from Strathmore.

Available now in 3-Packs and as part of a year-long subscription.

Intimacies is the type of book I’m naturally drawn to, a book of my usual taste, in other words. Here are lush sentences, a complicated woman narrator. Here are the topics I myself am intrigued by—complicity, translation and language, the way we see and perceive ourselves and others, how relationships elide clear boundaries. As a writer currently working on a novel about witnessing, these lines felt like a beacon:

But none of us are able to really see the world we are living in—this world, occupying as it does the contradiction between its banality (the squat wall of the Detention Center, the bus running along its ordinary route) and its extremity (the cell and the man inside the cell), is something that we see only briefly and then do not see again for a long time, if ever. It is surprisingly easy to forget what you have witnessed, the horrifying image or the voice speaking the unspeakable, in order to exist in the world we must and we do forget, we live in a state of I know but I do not know.

Kitamura has created a narrator who examines herself and others with a crystalline eye. The novel is one of layered intimacies, and as each one opens up, they call into question the other relationships around this woman, to a slow and ingenious satisfaction.

What I loved about The Trees and Intimacies was how they examined overlapping topics and questions about the history of evil in humanity, crime and punishment, and who should be the bestower of these judgments—in radically different ways. The voice, tone, and scope come from opposite sides of the literary spectrum—from the close first-person perspective of Intimacies to the raucous third-person perspective of The Trees, the contained world of a transient woman in the Netherlands to a narrative that begins in Mississippi and reverberates across the United States.

I will say it was very, very hard to choose between these two novels, but for the purposes of the grand Tournament of Books, I am going to choose, perhaps surprisingly, Percival Everett’s The Trees. I’ve made this decision precisely because it’s the novel I wouldn’t have necessarily picked up if it weren’t for this judging, and I am so grateful to have found my way to it through this role. The Trees jolted me out of my usual reading experience. It is over the top and gravely serious, rooted in a deep anger over the disgusting history/present of lynching and death and the murders of Black people that happen again and again in this country, without reprieve or justice. In one scene toward the end of the novel, one of the main characters, Gertrude, says:

“Everybody talks about genocides around the world, but when the killing is slow and spread over a hundred years, no one notices. Where there are no mass graves, no one notices. American outrage is always for show. It has a shelf life.”

And though the man she is talking to, Jim, wryly remarks, “You’ve been sitting here rehearsing that speech?”—what Gertrude says is true. As Intimacies perceptively notes, it is surprisingly easy to “live in a state of I know but I do not know.” I love that Everett commands us to break down that boundary, to see, to remember and learn and face our own faults in wanting to look away.

2022 may have begun in a state of unmooring for me (and for us all, let’s just acknowledge Year Three of the pandemic, shall we?) but these books have grounded me. They have reminded me to acknowledge our world instead of detaching, to look and learn and relearn. I still believe dreams are portents, but as Mama Z would probably say, so is our history.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile (he/him): Several years ago, the Tournament of Books had an official statistician. His name was Andrew Seal and he was awesome. He had his eye out for trends (“how does book length factor in first-round matchups?”) and basically gave you and me lots of stuff to ponder and discuss.

John Warner (he/him): As I recall, it was an extension of the overall reductio ad absurdum that is the Tournament of Books itself, an injection of Moneyball into the mix that for me showed that while it’s certainly possible to use data to create the appearance of a rational gloss on what goes on here, that doesn’t mean the data is actually predictive or meaningful beyond the “Isn’t that interesting” response, which I recall having frequently, thanks to Andrew Seal.

Kevin: Mr. Seal left after a few years and we never replaced him. I miss Andrew, John. Because without his stats, my inherent laziness is going to lead me to do something I shouldn’t do right now, which is wildly speculate. I have no actual evidence to back this up, but it seems to me that when a judge mentions that they read one of the books on their own, before they assumed the duties of a Rooster judge, that book, more often than not, loses the match.

Now it could be that this is not even true and my feelings are bullshit. It’s also possible (or even probable) that there is a bias inherent in the premise. That the only time a judge even mentions that they read and enjoyed one of the novels before it was named to the shortlist is to establish an expectation they can then subvert by choosing against it. But I think it’s also possible that familiarity sometimes works against a novel in the Tournament of Books.

John: There is the additional factor that for Judge Kim, Intimacies was the kind of book she normally gravitates to—and was rewarded by that impulse—but still she went with the more recent and less familiar.

You might be onto something. It is interesting how our sense of a book changes with time. I am pretty lousy at remembering specific plot points or fine details about books, but I tend to retain the feeling the book invoked in me. The Trees grows in my estimation over time because being triggered by Judge Kim’s ruling to think again about the book, returns a literal sense memory of what it was like for me to read The Trees.

As amazing as our capacity to retain these reading experiences is, I’m often equally amazed by my ability to forget a book, even a book I apparently really liked. While I have pledged to myself to not buy books from Amazon, I do use their wonderful database to look things up, and recently their algorithm served up a recommendation of a book titled The Regional Office Is Under Attack by Manuel Gonzales. The description made the book sound interesting. I scrolled through the blurbs culled from reviews. One of them said, “‘A hugely entertaining read.’ —The Chicago Tribune.”

Now, for the last 10 years, particularly in the last five, when a book is talked about in the Chicago Tribune like this, it’s often me who’s doing the talking, and yet I had no specific memory of reading it. I searched and sure enough, I’d honored the book in a mid-year Biblioracle “Books of the Year” column in 2016. I labeled it the “most fun book I’ve read in a long time.”

After a while some stuff about the book came back to me, but apparently “fun” is not an experience that sticks with me. Not sure what that says.

Kevin: I’ve got more bad news for your doctor, John. You told me to read The Regional Office Is Under Attack and I loved it. I also did not remember any of that happened until three minutes ago.

You know what I do remember? The first time I heard “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” I was walking down a street in Chicago and it was playing inside a store with the door open, and I stopped on the sidewalk and was like, “What is this?” It was both different from anything I had heard before but also instantly grokable. It’s an imperfect, cross-media analogy, but The Trees holds a similar quality for me.

Intimacies is an excellent novel and quite innovative in its own right. Another outstanding book falls victim to the Rooster game of this or that.

John: That’s an interesting comparison because I also remember the first time I heard “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” though it was being played by a band named Busker Soundcheck at a frat party, spring 1991 at the University of Illinois, six months before Nirvana would release Nevermind. In between sets, I went to tell the band how great that one song was and they admitted it wasn’t theirs, that they’d heard it live when touring the Pacific Northwest and were blown away by this band Nirvana, whom they said were going to be huge.

It’s interesting to think about what art leaves a permanent imprint and why.

Kevin: I like to think one of the guys from Busker Soundcheck periodically googles that name to see if anyone remembers them, and this week, after decades of disappointment, will finally get an electric thrill.

A quick check of the Zombie voting reveals that Intimacies does not have the dead-brain fuel to make it into the top two. If the Zombie Round were held today, our goo-splattered Gutenbergs would still be Klara and the Sun and Matrix.

New 2022 Tournament of Books merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

- We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.