-

March 11, 2022

Opening Round

-

Lauren Groff

1Matrix

v.

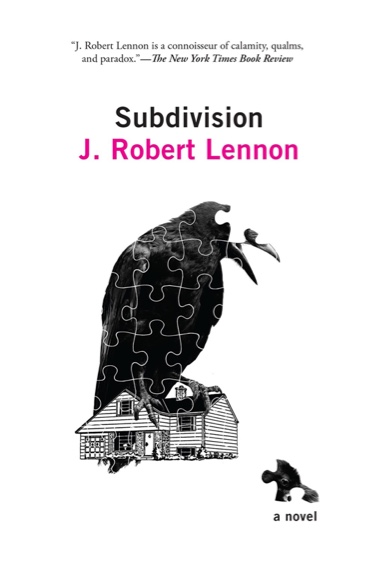

4SubdivisionJ. Robert Lennon

-

Judged by

Carole V. Bell

While I eventually got there, for a long time I had trouble finding any way to weigh what these two books meant to me. I floundered grasping at the usual points of connection and comparison. In the end I had to go with feeling.

A sense of cool unreality pervades J. Robert Lennon’s Subdivision. Like its striking cover with a drawing of a monstrously sized jigsaw puzzle of a black crow sitting atop a house, it’s creepy and atmospheric in an overtly symbolic way. The novel’s first-person narrator has no name and no memory that she can access. She’s a stranger in a strange place, and she seems to have no past. She can’t even remember the last time she ate or who she was with.

When she enters “the subdivision,” the woman checks into a curious guesthouse whose proprietors share both a name (“Clara”) and occupation (they used to be judges). The women assign the newcomer to a room named “Mercy.” All of the rooms in the house have symbolic names like “Virtue”, “Duty,” and “Glory.” And they invite her to work on the seemingly impossible task of completing an extremely challenging jigsaw puzzle in the common room. The puzzle is about three feet by five feet, with tiny pieces and little gradations of color or pattern. A puzzle within a puzzle: “The longer I stared at the puzzle, and the more awkward our reverie—mine and the ladies’—became, the less I thought I could perceive in the scattered pieces. They were so tiny that the information they conveyed could mean literally anything.” Was this a metaphor of what was to come in the novel, I worried. After the first night, the hosts send the woman without name out with a map and a list of potential employers and places to rent in the Subdivision.

Early on, reading Subdivision made me recall Gus Moreno’s The Thing Between Us, another novel in which the line between dream and reality is fuzzy and a potentially sinister smart speaker also plays a role. I was already on guard with the mysteriousness of the narrative, but when the electronic personal assistant/smart speaker “Cylvia” entered the story (like a generic Alexa but ultimately so much more) it heightened my senses, making me think horror was in store.

But while The Thing Between Us quickly runs hot, the unreality of the woman’s situation grows more surreal and puzzling with each interaction in the subdivision. But the woman doesn’t freak out. She just keeps rolling. When she’s house-hunting for instance, she encounters a handsome man with a house to rent who matter of factly explains about his windows:

“These windows aren’t event-tempered against narrative re-polarization. You can’t get windows like these anymore—there are too many manufacturing regulations! Yes, sometimes you’ll see the future through them, or the past, or some alternate version of the present. But they really let the light in on sunny days, and they’re easy to clean.”

No big deal, just a magical window onto another time. Apparently the house was built in a “probability well.” What is that? We’ll get there later, but it has something to do with alternate realities and physics. In this strange place the woman sees into her past: “Into the bedroom—our bedroom, Jules’s and mine—and then out the other window, to the moonlit street, where my preteen self stole away with my little sister, whom I had decided to raise on my own, away from the environment of selfish indifference our feckless parents had created.”

The childhood scene intrudes on the woman’s plans, just as she experiences the first potential bit of raw emotion on the page, a sexual attraction to her potential landlord, and she doesn’t take it well. “My initial reaction to this scene was annoyance. How dare these disturbing alternate realities interrupt my seduction of this beautiful, smoky man!” The closer she gets to connecting physically with the smoky, sexy landlord (who turns out to be nothing he seems), the more alarmed her personal assistant Cylvia gets until the device turns red, issuing warning after warning.

“Do not eat the apple,” Cylvia said. “Do not eat the apple. Do not eat the apple.” … “You must not reside in a probability well,” Cylvia said. “You must not fornicate with the bakemono.” … “The bakemono will trap you. Do not eat the apple. Do not fornicate with the bakemono.”

What’s the bakemono you might ask? Well that’s a really neat part of the story. My recommendation: Don’t look it up before you read this. After that, things get even more surreal. I’ve never taken acid, but I imagine if I did it might feel something like this.

Subdivision is clever and sometimes darkly funny (the creepy birthday song will live forever in my memory), but infinitely slippery. Like an adult Alice in Wonderland, heavily steeped in metaphor, things keep getting curiouser and curiouser the deeper you burrow into this mysterious rabbithole of a subdivision. It’s a wild, imaginative ride, increasingly unsettling and menacing, with clarity just always just out of reach.

Bright and warm, the covers of these Memo Books are heavily debossed with graphic patterns based on flowers that are among the very first to appear each spring, and then stamped with three luscious, reflective foils. The dot-graph insides are made from a superb paper from Strathmore.

Available now in 3-Packs and as part of a year-long subscription.

Matrix was a wholly different experience. Though I haven’t thought much about them in years, I confess I long harbored a strangely sentimental fondness for the European Middle Ages, a period I spent a summer studying in a boarding-school setting in a humanities program for incipient nerds. A decade or two or three later, I wondered what it would be like to return to that time in this literary form. The experience was also nothing like I expected.

Lauren Groff has fashioned a strikingly modern novel from the life of a 12th-century legend about whom little original documentation remains. In 1158, judging her wholly unfit for marriage, Queen Eleanor banished her 17-year-old bastard orphaned relative Marie de France to a poverty stricken nunnery in an obscure rural province in England. It could easily have been a life sentence. Food was short and disease rampant. But rather than wither and fade, Marie thrives, becoming a leader and building a fierce community of women, eventually even challenging some of the gender-driven constraints they’ve been given about what women can and cannot do in their religion. That rise is all the more impressive for beginning in ignominy, with withering discussions of Marie de France’s ungainly body:

Oh bless her, sweet mother of god, Marie would not do at all would she, not at all, so tall, it was frankly obscene. Three heads taller than any woman should be, crown brushing the beams, bony as a heron.

Marie’s body is also notable for its smell: “Such a great rustic with leaves in her hair and a stink that frankly affronted.” Marie endures these humiliating assaults on her person in the Royal Court and then again when she first arrives at the priory. They’re meant to humble her, to put her in the rightful place, but they provide a starting point for what will eventually be an amazing ascension. Despite initial skepticism from the priory’s inhabitants, as prioress, Marie boldly forges a community run for and by women and girls. She becomes not just a leader, but a woman of vision, always expanding and strengthening their position.

Three decades into her commission, by the time Marie rises to become not just prioress but head of the whole abbey upon the old abbess’s death, her community is wealthy and the women in it have grown “fat.” Well, many have actually grown strong and well-muscled from taking on more manual labor in the many projects in their community rather than relying on the paid labor of men from outside, which brings its own danger. But the idea that they’ve grown fat is the legend that’s carried abroad and the overall point is the same: They have plenty of food to go around. So Marie’s consecration as abbess demands a great celebration and they can afford it, but that display of success is a double-edged sword (perhaps literally).

That’s typical—danger and political intrigue swirl constantly around them, every advance accompanied by potential threat. Yet for all the detailed, bloody historical context, Matrix also feels remarkably relevant. Matrix’s subject is centuries old but not archaic. It’s not just Marie’s story that is so compelling. It’s how it’s told: the vivid, specific interiority, the remarkable rhythm of the language, and the sheer strength of these characters. Without making explicitly feminist statements, I can’t think of a more feminist treatment of women’s aging. Take for example the experience of menopause, which for Marie comes with increased power and clarity:

By the time Marie was elected abbess, the heat of the end of her menses had withdrawn from her. Now she is no longer touched by the curse of Eve. When the blood stopped, the knives that had twisted in her since she was fourteen were at last removed from her womb.

She is given instead a long, cold clarity.

She can see for a great distance now. She can see for eons.

This portrait flips the religious interpretation of “the curse” on its head, to Marie’s advantage. If menstruation is a punishment, “a curse,” its cessation must be a blessing, and yet it’s not usually treated as such.

Eventually Marie reaches higher, even daring to buck the dictate that certain religious duties are rightly the province of men. Ever stronger and more radiant, she “glows with a light that is not of fire.” She’s quite literally a visionary, more than a little drunk with her own power and divinity, and surprisingly ruthless when needed. From castoff to transformational leader—such a rise is the stuff of legend or myth. It’s especially arresting with the poetic sensuality of Groff’s rendering and the gritty 12th-century context. Add to that my 21st-century discontent and the fact that took up residence in the back of my mind: how women’s roles in the Catholic church remain constrained today. All told, I couldn’t look away.

Though they both feature women starting over in extraordinary circumstances (and eschew the definite article in their titles), Matrix and Subdivision made for strange rivals. The differences in these novels are largely of form and intent rather than quality. Each one is fascinating and original; each excels in its own right. Ultimately the deciding variable was my own sensibility. While I have enormous respect for the innovative imagination of Subdivision, I’m an emotional reader, and this novel started slowly and struck me as frustrating and bloodlessly intellectual nearly throughout the first half. Even knowing there’s a good reason for that distance, it was hard to get past. That’s intentional and interesting, and I especially liked the absurdist elements, but that didn’t easily propel me forward. Unsure whether I was lost in someone else’s dream or an extended metaphor, I had trouble hooking into the narrative.

Where Subdivision was intentionally spare, Matrix was lush and humane—dirty and smart and surprising in its treatment of gender and sexuality. Where Subdivision was a cerebral fantasy I grew into, Matrix is messy, passionate, and propulsive, capturing my heart and head from the start. That and the sheer beauty of the prose gave me the answer. I chose the heart.

Match Commentary

By Kevin Guilfoile & John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile (he/him): I was much looking forward to this matchup because I love both of these novels, but before we discuss them we probably need a disclosure. Lauren Groff and I grew up on the same street at the same time in the same one-traffic-light town. We didn’t know one another back then because she’s younger than me (we have become very casually acquainted through email in recent years). I’ve mentioned this in past Roosters because Groff’s books have made regular appearances in the ToB (as they have on many best-of-the-year lists), but that is not because of our membership in some kind of Lake Street secret society. Although, now that I type that, it sounds like an amazing idea. (Lauren, DM me.)

John, you and I are both acquainted with J. Robert Lennon—you originally through the work all three of us did in the early days of McSweeney’s, and I have been in touch with him, sporadically, mostly because of my admiration for his novels.

John Warner (he/him): If I recall correctly, I met Lauren Groff at a writer’s conference where you and I and she were talking, well over 15 years ago, so I suppose I also know her, but that’s not the same sense.

It is interesting to consider the impact of social media on how we “know” people. The fact that I follow Lauren Groff and J. Robert Lennon on Twitter, and have interacted with them a handful of times, sometimes makes me feel as though I do know them in a sense, but it’s not true. The parasocial relationships we can develop with those we observe online are not friendships, even though we may know a lot about those folks and even feel like we’ve been in conversation with them to some degree.

Anyway, I don’t think any of that hampers our objectivity here because like you, these are two writers whose books I seek out sight unseen and they’ve always delivered for me, so yes, I was very hotly anticipating this matchup.

Kevin: Every year it seems like we have an existentialist underdog in the ToB starting gates, and every year I find myself rooting for it. They almost never make it past the first turn. Subdivision meets that fate this year, but to be fair, it had to get past a real thoroughbred in this round.

Subdivision has all the qualities that usually get labeled “Kafkaesque.” Its characters are navigating an absurd world, the rules of which are unclear. Much that seems obvious to certain characters is never explained to the reader. There is more entertaining action in Subdivision than in your typical existentialist novel, though, and it’s also more explicitly funny. Like all of Lennon’s novels it is both highly original and broadly appealing.

John: Reading the description in the judgment makes the book sound much stranger than I think it reads, which is to say that I think it does a great job of orienting you to the logic of the world and then salting additional oddities as we go in a way that felt very natural and easy to follow. When you extract it all in summary, you might start to think that the whole thing is off its rocker, but in the telling, it makes itself seem wholly plausible.

Kevin: Also, every year the Rooster develops a kind of accidental theme that is only noticeable after you’ve read much of the shortlist back to back, and this year I think there is a recurring motif involving artificial intelligence (and, relatedly, doppelgangers). Cylvia, basically a Siri or Alexa device, is the narrator’s sidekick and develops into an important character with far more knowledge than the narrator, which they selectively reveal on a kind of need-to-know basis. Cylvia seems to represent, in part, the evolution of a source of anxiety for humans, whose decision-making has always been hamstrung by imperfect information. Now we have access to virtually all the information in the world, but our difficulty in analyzing it and distinguishing fact from fiction has led us into all kinds of existential trouble.

John: Existential trouble is a good way of thinking about what animates Subdivision, and the depth and scope of that trouble is what really elevated the experience of reading it for me. We ultimately do discover what this trouble is grounded in, a conclusion which I found emotionally potent, and all of the surreal trappings absorb into the narrative in an organic and satisfying way. I’m really pleased we were able to share it as part of the Tournament.

Kevin: It’s almost a cliché in literary discussions to express frustration that a novel you were enjoying so much has an ending that disappoints. Endings are hard and I am pretty forgiving of them so long as they don’t betray the reader in some way. I think Subdivision really nails the landing, which is exciting.

Alas for Cylvia and company, there is so much to admire in Matrix, which Judge Bell does a terrific job of summarizing. The prose is, of course, wonderful, but even beyond that Groff does so much work on the reader’s behalf. She clearly did a tremendous amount of research and thought carefully about every word on the page. It’s such a confident work. The primary engine of the plot—Marie’s visions—don’t start until relatively late in the novel, but the reader always knows they are in good hands.

And it seems like I shouldn’t have to mention it, but for a work of historical fiction with this kind of scope, spanning decades, with virtually no male characters, feels a little daring and wonderful. (There are male presences—the Pope, for instance, and some mostly faceless townspeople—but they have almost no speaking parts.) This allows Marie, even in the context of the 12th century, to be a powerful force in her world, kind of like Joan of Arc and Nancy Pelosi and Margaret Thatcher and Madeleine Albright rolled into one.

John: Matrix was my favorite reading experience of the year, an experience I found so enjoyable I wrote an entire column at the Chicago Tribune about how I was purposefully having a “slow book” experience as I read it. I read no more than one chapter a day and built in a little meditative reflection time after that on what I’d just read, a reading equivalent of the final Savasana pose in yoga. For the period of time that I was reading the book, it had tremendous salutary effects on my mental equilibrium. It takes a special kind of book to achieve this state, and I haven’t found one that quite fits the bill since. If anyone has recommendations in the comments, I’m all ears.

New 2022 Tournament of Books merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

- We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.