A Tooth for a Tooth

Modern dentistry does wonders for a rotten molar or a cracked bicuspid—it’s modern dental insurance that falls short.

In one of the oldest accounts of a dental operation, Archigenes of Rome advocated in pre-Christian times for drilling a hole into a pained tooth to remove its interior, morbid material. More than a thousand years before this recommendation, the ancient Egyptians wrote in the papyrus of Ebers that the best cure for bennut, or seed-like, blisters in the teeth, was to pack the mouth with fennel seeds and onions, among other things.

A more recent account of a dental operation begins with my favorite dental hygienist suggesting we get $1 beers at Taco Cabana and then telling me that the interior of my left maxillary first premolar had been reduced to the consistency of something at the bottom of a quarry.

I had just gotten a palate Novocain shot and was watching Extreme Chef on the television above me as my dentist did something criminally painful to the back of my mouth.

The television program had “recreated” the Dust Bowl by blowing dirt in the faces of contestants as they ran to collect pots and pans in a verdurous field. I was thinking, They’re going to remind me that I wouldn’t bleed so much if I ever flossed. I was thinking, I’m pretty sure this is nothing like the Dust Bowl.

It was while I was fighting the bite block and dribbling something inelegant down the side of my neck that I heard it. And when I started to sing along with the song softly playing on the office speakers, the dentist’s saw quit earthquaking my jaw and the hygienist stopped suctioning the saliva from the back of my throat. When they realized that the guttural noises I was making weren’t out of pain, they heard it, too. And that’s when my hygienist started to sing along with me to Brian McKnight’s “Back at One.”

For about 45 seconds, we three seemed to couples-skate back to 1999, when McKnight’s pretty ballad ruled the charts, when I watched Felicity in my dorm room, when I was safely embraced by my parents’ health and dental insurance. And then they went back to the terrible things I was paying them to do.

In an article in the June 2000 issue of Ebony, McKnight explained the impetus for the song: “I was sitting here trying to figure out how to work my DVD. The manual tells you if you make a mistake, go back to step one.” Much more recently, he mentioned in another interview that he was reading that manual on the toilet.

What we know as cavities are more formally known as caries, but that word just means the progressive destruction of any kind of bone structure. I have carried many caries in my 33 years, all in my teeth. But you can get them in your skull. In your ribs. And maybe the plan you purchase on the new health exchange will pay for that.

The number of people without dental insurance in this country is three times the number of people without general health insurance. In a June 2012 episode of PBS’s Frontline, “Dollars and Dentists,” the narrator revealed a figure I had never pondered but was not surprised to learn: More than 100 million Americans cannot afford to go to the dentist. That number includes as much as 70 percent of all seniors, because Medicare does not cover cleanings, fillings, root canals, or pretty much anything that isn’t related to some other, non-dental condition, in addition to nearly every adult on Medicaid, since most states only cover children’s dental care, and that’s, of course, only if their parents can find a provider willing to take their little ones as patients. This happens less often than you might imagine and is particularly upsetting because tooth decay, according to the American Association of Pediatric Dentistry, is “the single most common chronic childhood disease.” A recent study from the University of Southern California Ostrow School of Dentistry showed that poor oral health in children is connected to missed school days and lower grades, leading the researchers, who published their results in the American Journal of Public Health, to call for “widespread population studies … to demonstrate the enormous personal, societal, and financial burdens that this epidemic of oral disease is causing on a national level.”

The treatment costs you twice as much as it does for those who have insurance.

In the years since I graduated from the dorms in 2002, Keri Russell has given up her curls and I have had dental insurance for a combined two, non-consecutive years. Six months here, a year there, another six months that ended long before I wrote this.

One of the most infuriating aspects of getting private dental care when you’re uninsured is that the treatment costs you twice as much as it does for those who have insurance. That crown you need so you don’t end up like me, needing yet another extraction, which results in your dentist having to fracture your jawbone to pull the tooth? My dentist, for example, charges $914 if your insurance is going to pay for it. He charges $1,373 if you’re going to. And that makes dental sense: If you can’t afford it, it costs more.

I have been resourceful, though. While in graduate school, I went to the College of Dentistry at the University of Illinois at Chicago to get an almost-affordable root canal from student dentists. During my first appointment, there were 20 of us in one large room, like a field hospital. The days of a private space where I didn’t have to watch an elderly man’s dentures get refit while my own mouth was tended to seemed like a heady dream. Listening to the whimpers of pained strangers, I learned an incredibly important lesson I have never forgotten: We’re all fucked.

Or to rephrase: “Tooth decay is the province of the poor.” Or perhaps, to add an addendum to that rephrase: “Tooth decay is also the province of the somewhat privileged whose shallow pockets are filled with advances on school loans.”

Because my liver processes anesthetic remarkably quickly, and my dental student wasn’t able to offer me gas or better drugs, as the clinic was scheduled to close she finished the last few minutes of my root canal without anesthetic. I told her to. And then I square-breathed my way out of my body, counted to four, held my breath for four, exhaled for four, and held the exhale for four through the tears to mentally separate myself from a hurt so tremendous it even had a sound: like a very high note on a badly tuned instrument.

These kinds of options have been available in nearly every city I have lived since, and I have taken advantage of them. My parents, who aren’t in a position to help, have assured me it’s OK. They tell me: You’re not taking advantage. After all, an estimated 45 million Americans under the age of 65 have no dental insurance. Is it really taking advantage if so many of us do it?

In 2012, U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont co-authored the Comprehensive Dental Reform Act. Among the many valuable programs left to languish when the bill died in committee: the extension of comprehensive dental coverage to everyone receiving Medicaid, Medicare, and veterans’ benefits and the support of programs to recruit and train dental therapists, akin to nurse practitioners, who could offer services at lower costs.

A dry socket angrily emerged in my gums. Friends brought every drug from their secret stashes to try to ease my pain. Nothing worked.

A few years after my square-breathing debacle, I was scraping by with health insurance provided by my doctoral program, when I took a bus to the University of Colorado School of Dental Medicine in Aurora. On my first visit, they took a look at the tooth I’d had root-canaled in Chicago, the one I couldn’t afford to get capped, even at reduced prices, and they told me it had to go. They said they could put in an implant, which would be more expensive than every car I have ever owned, combined. So I told them the only thing I could: Come and take it. But really, seriously, just rip it out. And they did, and then they sent me on my way, to the car where a friend was waiting to drive me home. With no painkillers.

That night, a dry socket angrily emerged in my gums. It was Friday. The office was closed and the recorded message informed me that I wouldn’t be able to see anyone until Monday. Friends brought every drug from their secret stashes to try to ease my pain. Nothing worked. I finally resorted to banging the right side of my face against the wall for hours, after the Old Chub and Tylenol PM had worn off.

If only I had known then of the homeopathic recipes used in previous centuries: “Roast a bit of garlic and crush it between the teeth; mix with chopped horseradish seeds or saltpeter; make into a paste with human milk; form pills and introduce one into the nostril on the opposite side to where the pain is felt.”

That solution would have been about as productive as relying on the Affordable Care Act, which doesn’t lower dental costs, increase access to dentists, or seek to improve the overall oral health of adults. We hear a lot about the importance of preventative care when it comes to everything but our mouths; we hear less about the fact that oral diseases and infections that go untreated can lead to respiratory and heart disease, diabetic complications, and even pre-term birth and low birth-weight. We hear even less about the fact that an abscess in your upper gums can lead to sinus infections, and that that abscess can migrate to your brain. We hear almost nothing about the fact that the morbid material in your teeth can be lethal.

Last January, Massachusetts reinstated some of the dental benefits for adults on Medicaid that had been previously cut in its state health plan. The state is willing to now pay for fillings for adults, but only on the front teeth. Is something in the back of your mouth killing you? Are you going to survive what is happening to your gums? It doesn’t matter, as long as what your boss can see of your face doesn’t make him sick.

The “Path to Prosperity,” Rep. Paul Ryan’s 2012 budget, proposed cuts to Medicaid that the Kaiser Family Foundation warned would even further honey-badger the teeth of disadvantaged adults. Then vice-presidential-candidate Ryan had apparently not read the 2000 publication, “Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General,” which called the disparities in the dental care of American citizens a “silent epidemic.” But who needs better entitlements that might erase epidemics and create a true path to prosperity? Something about tooth for a tooth, unless you knock out a slave’s tooth, and then it’s half a mine of silver, and all that.

The state is willing to now pay for fillings for adults, but only on the front teeth. Is something in the back of your mouth killing you?

In ancient China, people believed there were worms in the teeth that caused pain, and that the way to kill them was with arsenic, made into pills, placed near the aching tooth or into the ear opposite the throbbing. Arsenic. For the uninsured. Perhaps that’s an entitlement that would encourage Republicans to not shut down the government?

In 2011, 33.3 million people lived in what’s known as a health professional shortage area, meaning that even if they could afford to visit a dentist, there’s not one within driving distance. It’s what’s called a dental desert. According to the Department of Health and Human Services, that number grew to 49 million in 2012.

With nowhere to go and no way to pay, in 2010 more than two million Americans were treated in emergency rooms for preventable dental problems, which the ADA Health Policy Resources Center estimates cost the health-care system somewhere between $867 million and $2.1 billion. Regrettably, emergency room doctors can only control an infection, treat the pain, and then tell their patients, who wouldn’t be there if they could go to the dentist, that they should go to the dentist.

Avenzoar, the renowned Arab physician of the Middle Ages, once explained that “the extraction of teeth was sometimes inflicted as punishment for having eaten flesh during Lent or on those found guilty of felony.” Now, as a result of lack of access to affordable care that would prevent those teeth from needing to be pulled, it’s most likely the latter, plus those who have been convicted of being poor. Those people that Mitt Romney defined as people who are “dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it,” dental care clearly being included in this category. Obviously, some think, the problem is not that your nearest dentist is a tank of gas away, or that your visit will ensure your family can’t eat dinner for the next month, it’s that you will never “take personal responsibility and care” for your life or teeth.

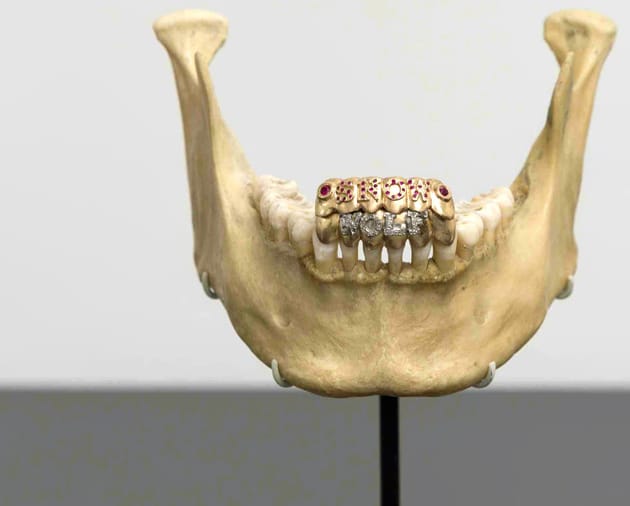

Saint Apollonia, canonized in 300 A.D., is the patron saint of dentistry and all sufferers of toothaches. When she refused to renounce her faith, her persecutor had all of her teeth knocked out. When she was threatened with being burned alive unless she abandoned her religion, she jumped into the flames. She’s often depicted in paintings with a golden tooth at the end of her necklace, and is sometimes seen with pincers, delicately holding a bicuspid. It doesn’t appear that she’s answering very many of our prayers.

In 2006, Brian McKnight was featured with the Big Phat Band on the Take 6 cover of the jazz standard “Comes Love,” which grand dames Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald sang decades before. Among its lyrics:

Comes a headache, you can lose it in a day.

Comes a toothache, see your dentist right away.

Comes love, nothing can be done.

For the 25% of Americans ages 65 and older who already have lost all of their teeth, nothing can be done. For the demons and worms at work in the mouths of millions of us without dental insurance, nothing can be done. We all have had better luck with love.

Or at least similar luck, if we’re fortunate. My most recent visit to the dentist ended in tears. Not because I had split open a tooth, which had to be extracted, and not because it was on the same side of my mouth where another tooth had been removed, meaning I needed an acrylic to save my other teeth from a similar fate; not because I was uninsured and feeling doomed and in a considerable amount of pain, and not because I was envisioning a future of gummy smiles in family photographs. But because my dentist put his hand on my shoulder and said he would charge me the insured rates. I sobbed in the chair, grateful for his kindness, and put $1,293 on my credit card.