The Long Tail of the Attica Prison Riot

The Attica prison uprising lasted five days. It took 45 years to get a more or less complete public account of what transpired—and only thanks to the efforts of a few heroically stubborn people.

Shortly before 9:45 a.m. on Sept. 13, 1971, the fifth morning of the Attica prison uprising, hundreds of prisoners milled in the yard, waiting with increasing dread for news of any developments in their ongoing negotiations with New York state authorities. At 9:46, they got their answer. A helicopter thundered overhead and began blanketing the yard in billowing clouds of tear gas. In fact the tear gas was partly a powder: CS, a weaponized orthochlorobenzylidene compound then popular a world away in Vietnam, where the US military used it to flush Viet Cong out of the jungle and into the sights of waiting gunships. In footage of the Attica retaking, you can see a domino wave of people crumpling as the cloud of CS rolls over them.

The powder hung in the air like a dense fog, clinging to the prisoners’ clothes and working itself into their skin and lungs and further obscuring the vision of the gas-masked state troopers gathered for the assault. As the prisoners collapsed, choking and retching, the police opened fire. Over the next several minutes, they poured hundreds of rounds of gunfire into the yard, including, a judge later estimated, between 2,349 and 3,132 pellets of buckshot. The prison yard was transformed into a charnel house. The prisoners, who had no firearms, were sitting ducks, as were the hostages that the police had ostensibly come to save. As police and corrections officers stormed the prison, they sometimes paused to shoot inmates who were already on the ground or wounded. A helicopter with a loudspeaker circled overhead. “Surrender peacefully. You will not be harmed,” it announced as unarmed prisoners were mowed down.

After the shooting ended and the gas cleared, National Guardsmen came through, collecting bodies and dumping them in rows on the muddy ground. The final death toll of the Attica riot and retaking was 43 people, including one corrections officer fatally wounded during the initial uprising, three prisoners killed by other prisoners, and 39 people killed by authorities, including 10 hostages—captive corrections officers and civilian prison staff killed by the troopers’ indiscriminate shooting.

A young law student named James Watson was one of the National Guardsmen deployed at Attica to provide “medical support,” and body removal, for the retaking operation. His memory of the day has grown hazier over the years, but one image has stayed with him. “All I can remember is when we [left] everybody was cheering, [but] I sort of had tears in my eyes,” he told me recently in a phone interview. “It just didn’t seem like that’s what America stood for. It just seemed like…this isn’t real, this didn’t happen. There was a disbelief… a suspension of belief in what had just happened.”

There seemed to be a revolution underway, but, like many revolutions, it would end tragically.

Today, almost half a century later, popular memory of the 1971 prison rebellion at Attica Correctional Facility in Upstate New York has faded. Thanks to the iconic 1975 film Dog Day Afternoon, the phrase “Attica! Attica!” lives on as a kind of catch-phrase. But the five-day uprising was a defining political moment that encapsulated the tensions of a society already disintegrating over Vietnam and the Kent State shootings a year earlier. For those directly affected, it was a brutal experience. The psychic wound, for many survivors and their families and the families of Attica’s victims, has never healed, and some remember the event as if it happened yesterday.

Yet it took 45 years to get a more or less complete public account of what transpired—and only thanks to the efforts of a few heroically stubborn people, including Heather Ann Thompson, a University of Michigan historian and the author of last year’s Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. The first comprehensive history of the Attica saga, Blood in the Water is the product of 13 years of research and access to a trove of previously unseen documents. At 724 pages long, including more than 100 pages of citations and notes, it is an exhaustive chronicle of the Attica uprising and retaking as well as the decades-long fight by Attica survivors and whistleblowers to demand restitution and challenge the state’s attempt to whitewash criminal acts committed by law enforcement during the retaking.

There are some people who may have preferred the book unpublished—not least because of Thompson’s decision to include the names of state troopers and corrections officers suspected (but not convicted) of having killed prisoners. But from the start the book presents a less than flattering account of the state’s role in what became an ugly saga in US history.

Although the Attica uprising is often described as a “riot,” that is, in Thompson’s telling, misleading, even if it did start as one. Attica was a hellhole, and desperate prisoners had been trying for some time to get the state to address dire problems: extreme prison overcrowding; horrific food and sanitation; lack of medical care; and tension between the mainly black and Puerto Rican prisoners and the almost entirely white guards.

Tension was already close to boiling point when, on the morning of Sept. 9, 1971, protesting prisoners unlocked the cell of an inmate who had been confined there awaiting disciplinary action. Shortly thereafter a group of prisoners returning from breakfast was unexpectedly locked into a tunnel. Believing (incorrectly) that guards had trapped them in the tunnel in preparation for a retaliatory attack, prisoners panicked, attacked an officer, and began battering open the tunnel gates. The prison exploded. Prisoners overran several cell blocks and tunnels and seized control of D-Yard, a prison yard the size of two football fields, and “Times Square,” a central intersection of corridors. They took several dozen officers and civilian administrative staff hostage and began running amok and destroying parts of the prison.

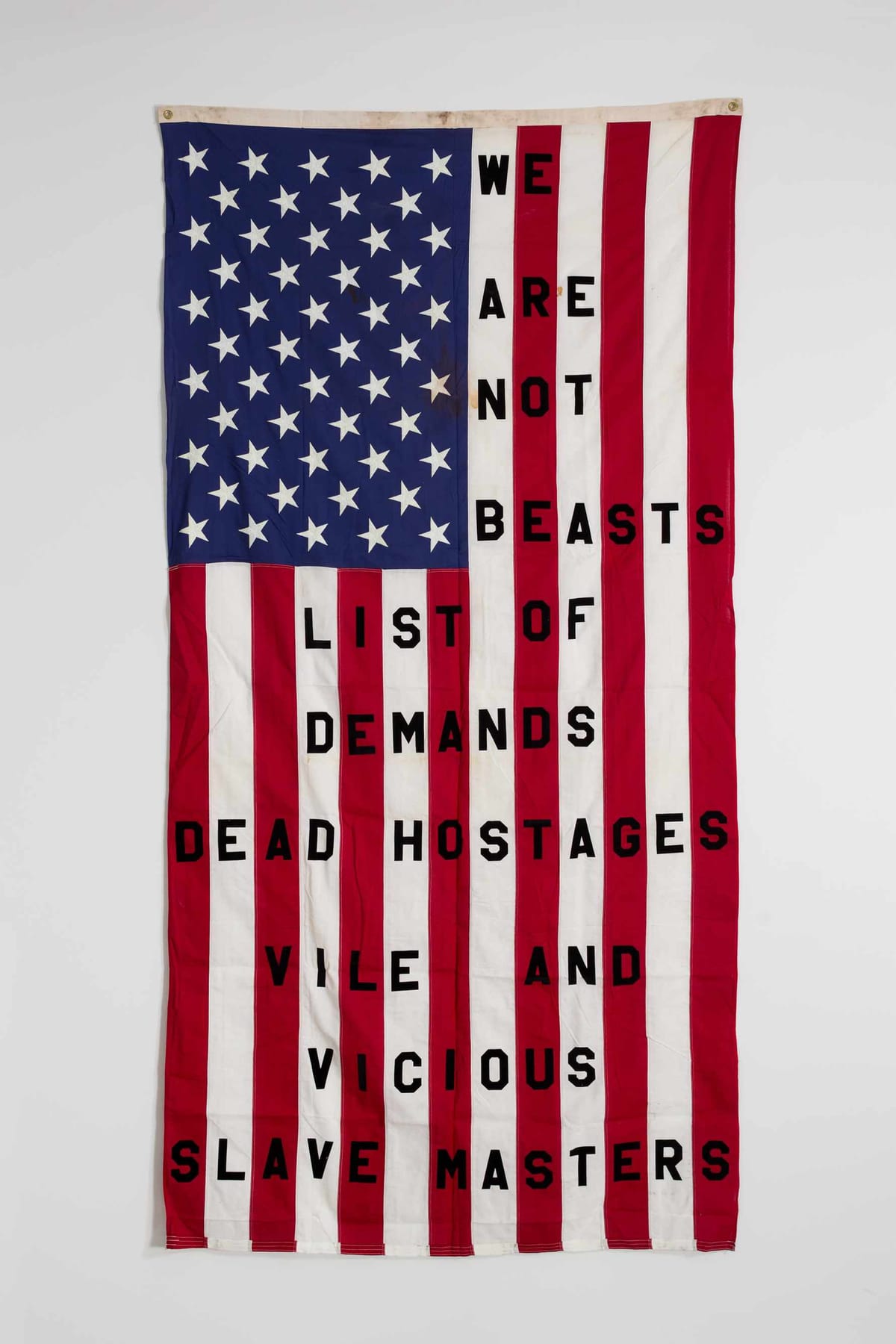

The chaotic uprising was unplanned and initially leaderless but over the next few days began to organize around a sense of revolutionary purpose. The prisoners built barricades, elected leaders, and drafted a series of political demands that ranged from vague and wildly unrealistic (mass amnesty and transport to a “non-imperialistic” country) to highly specific and concrete (an end to censorship of mail and reading materials).

The prisoners requested the presence of a team of neutral outside observers, including New York state assemblyman Arthur Eve and New York Times reporter Tom Wicker. At considerable risk to their personal safety, the observers entered the prison yard to meet with the prisoner leaders. Instead of violence and anarchy, however, they found that the prisoners had organized a surprisingly disciplined provisional government, with teams distributing food and first aid. The hostages were well cared for, and, as Thompson and former hostage Mike Smith have noted, a group of black Muslims volunteered to guarantee their safety. There seemed to be a revolution underway, but, like many revolutions, it would end tragically.

The bloody outcome, it becomes clear in Thompson’s hour-by-hour, minute-by-minute account, was the result, to a great extent, of conscious political choices by the state. New York authorities, led by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, had little to no interest in achieving a peaceful resolution. According to Thompson, Smith, and outspoken former prosecutor Malcolm Bell, there was an unsavory constellation of factors influencing authorities’ thinking: Nixonian paranoia of communism and black militancy; fear of prison populations being further contaminated by radical politics; desire to make an example of trouble-making inmates; and political pressure on Rockefeller, a liberal Republican governor trying to move into national politics, to affirm his law-and-order credentials.

The final blow for any hope of a peaceful resolution came on the third day, when a guard died of wounds sustained during the initial riot. This made the issue of amnesty for the prisoners, already a sticking point, critical. Both sides hardened in their positions, negotiations deteriorated, and the situation began spiraling with frightening speed.

The state’s decision to retake the prison with a poorly organized, unaccountable, and heavily armed taskforce—in reality, an undisciplined posse of 230 angry and sleep-deprived state troopers, park police, and corrections officers from across the state, untrained in riot control and boiling in rage over false rumors that prisoners had murdered and castrated hostages—was the cause of avoidable mass casualties. But it was only the first in a series of outrageous and probably criminal actions by the state, and only the beginning of a story that would stretch across decades.

Mike Smith is someone who has spent a lot of time thinking about Attica. Smith, then 23 years old and recently married, had just started as a rookie corrections officer at Attica when the riot broke out and he was seized as a hostage, he told me in a recent phone interview.

On the third day of the uprising, after learning that corrections officer William Quinn had succumbed to his wounds, the inmates realized that the likelihood of a negotiated outcome was rapidly shrinking. Smith and the hostages also realized the end might be near. If they had any lingering doubt, that night a Catholic chaplain asked to be admitted to offer the hostages last rites.

The next morning the prisoners, now in a state of panic and desperate to gain negotiation leverage, threatened to execute some of the hostages. They grabbed Smith and several others at random and brought them onto to the catwalk overlooking the prison yard and prepared the scene of a group execution. Smith was given a chair to be more comfortable and offered what he believed would be his last cigarette.

As the prisoners had no guns Smith was, he recalls, assigned three would-be executioners—one with a knife, one with a homemade spear, and one with a ball-peen hammer. The one with the knife was Donald Noble, a prisoner with whom he had a good rapport and who had protected him during the riot. They exchanged contact information for their families and agreed that if either survived he would let the other’s family know that he had expressed his love for them in his final moments. Smith also scrawled a goodbye note to his wife on a dollar bill in his wallet. Noble assured him that if he had to execute him he would do so as swiftly and painlessly as possible.

Then the helicopter rose above the prison walls, showering everyone in C.S., and shooting started from every direction, and “all hell broke loose.” Smith was shot four times across the abdomen—by someone firing, he believes emphatically, a fully automatic AR-15—incidentally a rifle then issued to servicemen in Vietnam—and his arm was hit by a ricocheted pistol bullet. Noble, also wounded, pulled him to the ground. As Smith lay bleeding he watched as prisoners and hostages around him were riddled with gunfire.

The ground force stormed in. A trooper pointed a shotgun at Smith’s face, inches away, and appeared to be about to finish him off when a corrections officer grabbed the gun’s forend. “He is one of us,” he said. The trooper redirected his shotgun at Noble, also sprawled on the ground wounded. “He saved my life,” Smith said. The trooper raised his weapon and moved on in search of another target.

Smith was evacuated barely alive. He spent the next three months in intensive medical care. Before the riot he had clocked in at a healthy 218 pounds; when he was discharged from the hospital that December he says he weighed 120 pounds, could not walk, and was completely incapacitated. His intestines had to be reconstructed. His wife spent months nursing him back to health. “The state did absolutely nothing for us,” he said.

It was starting to become impossible for the state to keep hidden the full scale of the violence and incompetence of the Attica retaking.

The sordid affair continued after the retaking. After 10 hostages died during the disastrous “rescue” operation (including one who died of wounds later), authorities accused the prisoners of having slit the hostages’ throats, a false claim enthusiastically reported as fact by newspapers across the country. Gov. Rockefeller and his top men held a secret meeting at his pool house to hash out the official narrative. Photo and film documentation of the retaking quietly disappeared. The stonewalling and whitewashing had begun.

But Dr. John Edland, the county medical examiner, refused to bow to political pressure to pretend the hostage deaths were caused by the prisoners—or to overlook the fact that many of the dead prisoners had clearly been shot in the back or at close range. Some prisoners, such as Elliot “L.D.” Barkley, one of the uprising’s most recognizable spokesmen, are believed to have been singled out and murdered after the prison was already retaken. To avoid trouble from the dead hostages’ families, who still believed that their loved ones had been killed by the inmates, not gunfire from law enforcement, state police canvassed funeral homes to pressure morticians into toeing the official line.

Edland was subjected to a campaign of ugly psychological warfare, including anonymous threatening phone calls, public smears against his professional credibility (including dubious attempts to paint Edland, a conservative Republican, as an unhinged radical sympathizer), and endless harassment. Over the next few years, according to Artvoice, a libertarian-leaning Buffalo newspaper, Edland was pulled over by state troopers at least 40 times. He sank into depression and alcoholism and was at one point institutionalized for half a year at a psychiatric hospital, noted the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle’s Gary Craig in a recent tribute to Edland. He eventually recovered, but Attica haunted him for the rest of his life.

It was starting to become impossible for the state to keep hidden the full scale of the violence and incompetence of the Attica retaking. In the face of mounting pressure, Governor Rockefeller ordered a public inquiry, the McKay Commission, held in 1972. Audiences heard wrenching testimony from prisoners as well as an unexpected source: numerous members of the National Guard, who came forward to describe scenes of state troopers and corrections officers torturing prisoners and denying them medical care.

“I think Attica brings to mind several things,” Dr. John Cudmore, a National Guard physician, testified before the Commission. “The first is the basic inhumanity of man to man, the veneer of civilization as we sit here today in a well-lit, reasonably well appointed room with suits and ties on objectively performing an autopsy on [that] day, yet cannot get at the absolute horror of the situation, to people, be they black, yellow, orange, spotted, whatever, whatever uniform they wore, that day tore from them the shreds of their humanity. The veneer was penetrated. After seeing that day I went home and sat down and spoke with my wife, and I said for the first time, being a somewhat dedicated amateur army type, I could understand what may have happened at My Lai.”

In 1973, Malcolm Bell, a 41-year-old Manhattan lawyer who had recently left the white-shoe civil litigation world to pursue an idealistic interest in criminal justice, answered a blind ad in a legal journal. It was a position with the New York attorney general’s office, which is how Bell unintentionally came to take on the sprawling, unhappy project of investigating crimes committed at Attica.

An army veteran and a Republican—“I voted for Nixon three times,” he recalled to me in a recent phone interview—Bell was an earnest and conservative square, not unlike medical examiner John Edland. The state, perhaps not by accident, had appointed the exact type of person one might expect to be instinctively sympathetic to the police and dutifully protective of the Rockefeller administration. But picking the straightest of straight arrows backfired.

As a measure of basic fairness, Bell believed the state had an obligation to investigate crimes committed by law enforcement officers during the retaking of Attica as aggressively as it was investigating crimes committed by the rioting prisoners. He spent a year scrupulously gathering evidence for the indictments of officers believed to have killed inmates. When his grand jury cases were suddenly suspended by his superiors, he began to suspect stonewalling at the highest levels.

Bell resigned in disgust, detailing his accusations of a cover-up in a 160-page memo to the governor’s office, then went to the New York Times. He later wrote The Turkey Shoot: Tracking the Attica Cover-up, a minor classic in the true-conspiracy genre. (Out of print, with used copies fetching more than $50 online, the book is slated for republication next month with a new preface by Heather Thompson.)

Disillusioned, and permanently blacklisted from a career in New York law, the one-time crusading prosecutor and establishment Republican eventually retired to Vermont, joined the Quaker church, and became active in the sanctuary movement, assisting efforts to harbor Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees in sympathetic US churches.

A few years before his death in 1991, Edland, the former medical examiner, gave his daughter a copy of Bell’s book, who later showed it to Gary Craig of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. Instead of a conventional dedication page, Bell had written: THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE GOOD GERMAN. EVERYONE CHOOSES WHETHER TO BE ONE.

Underneath Edland had inscribed: “This book is family history. It explains me. I hope it helps you understand why it all happened.”

Frank “Big Black” Smith, one of the prisoners elected to the provisional government, was among those tortured after the state retook the prison. (Corrections officers incorrectly believed that Smith had harmed hostages. In fact, Smith, who served as head of security, was responsible for protecting the hostages as well as the civilian observers who came to serve as mediators in the negotiations—though he was also one of those who ordered hostages moved to the catwalk and threatened with execution to deter a retaking.) Corrections officers beat his testicles with truncheons, Thompson notes, and forced him to play “shotgun roulette.”

Smith and dozens of other prisoners, collectively known as the “Attica brothers,” decided to pursue civil claims against the state. Smith, the son of a North Carolina cotton picker and the grandson of a slave, became a driving force in the effort to secure financial restitution for the prisoners. In 1974, Elizabeth Fink, a radical activist one month out of law school, was hired as attorney by one of the Attica brothers. The Attica cases would become the consuming project of Fink’s life, with Frank Smith as her paralegal. “Give us our day in court,” Smith told a judge in 1980, as recalled in his New York Times obituary. “We ain’t never had that.”

In 2000, 29 years after Attica, Smith and Fink went before a judge yet again. They won a $12 million settlement to be distributed among surviving prisoners and their lawyers. The state admitted no culpability. Frank Smith died of kidney cancer four years later.

Seeing the success of the prisoner settlement, the families of the prison staff killed and maimed at Attica formed a group called Forgotten Victims of Attica and began aggressively lobbying the state government. A major advocate for restitution was Mike Smith, the corrections officer shot five times during the retaking. Initially Smith was received with hostility by some of the other guard families, who perceived him as being overly sympathetic to the prisoners; many came, however, to recognize their common cause with the prisoner families.

Mike Smith and the families spent years lobbying for restitution. After the Attica retaking, some of the families—many of whom had lost their sole breadwinner—had accepted modest worker comp payments, not realizing that doing so abrogated them of the right to sue the state for civil claims. The state finally bent in 2005, agreeing to pay out another settlement of $12 million. Smith never got the apology he had really wanted.

“I never call anyone a murderer or say anyone shot anyone. I tell you what the state believed. That is a huge distinction.”

Blood in the Water has been justly hailed by critics and historians as a definitive account of the Attica trauma and a landmark contribution to the scholarly literature of American criminal justice. Thompson’s decision to publish the names of state troopers and corrections officers suspected of murdering prisoners has, however, proven divisive. Some of those named are dead; many are elderly. Thompson found the names in decades-old grand jury files, which are kept sealed to protect those who have been accused but not convicted of a crime.

“I have decided to include all that I have learned and seen in this book,” Thompson explains in the introduction. “That said, this decision was agonizing. Although my job as a historian is to write the past as it was, not as I wished it had been, I have no desire to cause anyone pain in the present. I am well aware, and it haunts me, that my decision to name individuals who have spent the last forty-five years trying to remain unnamed will reopen many old wounds and cause much new suffering.”

Thompson’s decision, and the book as a whole, have been received with displeasure by the New York state police union. “Through the years, the PBA has opposed the release of confidential grand jury testimony pertaining to the investigation of the incident,” New York State Troopers Police Benevolent Association President Thomas H. Mungeer said in a statement forwarded to me by his press officer. “It is the PBA’s duty and responsibility to not only protect the Constitutional rights of the Troopers who were forced to testify about their actions during the riot, but also to those who have had to recount the incident for decades because of criminal investigations and civil lawsuits.”

Former prosecutor Malcolm Bell, otherwise a strong supporter of Thompson (whose book he even helped fact-check), has questioned her decision to include names. “In my own case, the position is easy: I can’t name them,” he told me. “I was in the prosecutor’s office. I’m not allowed. In her case, I don’t think it would have been as much [of] an issue if this was at the time [of the original investigation]. But now, many years later…People can’t defend themselves. Many of them are dead.”

There is another problem: The grand jury documents were effectively “first drafts,” Bell said. “There is serious uncertainty about some of the officers named. At the time my office was completely certain that certain troopers were guilty of murder, but there were others where significant uncertainty about their guilt existed, and [Thompson] names some of those people.”

In a recent interview Thompson strongly disagreed with Bell’s reasoning. Bell thinks as a former lawyer, but historians, Thompson argued, are bound by much different ethical obligations. In piecing together a comprehensive history of what the state suspected, and, more importantly, what the state suspected and did or did not act on, she “cannot not report” that information, “because then I would be making a decision to privilege some of the historical information I’ve found over others.”

She also disputed the PBA’s implication that the book was slanted against law enforcement, noting that she also included, for example, the name of a prisoner—later acquitted—believed to have brutally killed another prisoner. Yet no one seems upset about that decision, she said.

“I never call anyone a murderer or say anyone shot anyone,” Thompson told me. “I tell you what the state believed. That is a huge distinction.” Ultimately, said Thompson, “I think who did the shooting is far less important than the fact that the state of New York marshaled every resource it had to protect those who had created such harm at Attica.”

Did Attica change anything? The prisoners’ demands and the later hearings and investigations did achieve some reforms, Thompson notes. New York prison authorities eventually implemented some of the reforms that prisoners had asked for: better medical care, better food, more political freedom, less mail censorship, parole reform.

On the whole, however, Attica’s legacy for American criminal justice was ugly. After Attica, the new mantra was: meet force with force. Prison officials vowed never again to negotiate with prisoners. Politicians rushed to secure greater tough-on-crime legislation, and mass incarceration became an entrenched feature of American society. Today the US has the largest incarcerated population in the world, with at least two million people behind bars, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

As for the Attica cover-up, the state’s whitewashing and stonewalling never truly ended, though in 2015 the New York attorney general’s office opened more files to the public. The files, from the previously unreleased second and third volumes of the three-part Meyer Commission investigation, have been extirpated of grand jury testimony; the resulting documents are too denatured to be of much insight. Thompson feels that the document dump is largely a PR move, calling it “disingenuous.” After years of refusing to respond to freedom-of-information petitions filed by Thompson and others, “the attorney general’s office is [now] trying to position itself as being a friend of releasing the documents,” Thompson said.

If anything, what seems most striking, almost half a century after Attica, is how little has changed. As if to underscore the point, last year prisoners across the US participated in one of the biggest prison strikes in history—involving thousands of inmates in 24 prisons in 23 states, according to the Los Angeles Times’ Jaweed Kaleem and others. Many of the prisoners’ demands were almost identical to those articulated at Attica. The strike received almost no media attention.

More recently, a two-day prison riot in Delaware left a guard dead, an incident which did receive wide media coverage. The incident puts a spotlight on the dangers faced by corrections officers, who often work alone, without backup, vastly outnumbered by their wards. “I really see both the COs and prisoners as [put] in jeopardy by the overcrowding and the punitive conditions that states allow to exist in their facilities,” Thompson said.

The guards, in an important sense, are locked up too. Perhaps that is why, in addition to risk of attack by prisoners, corrections officers suffer disproportionate rates of depression and, according to the Guardian, have a suicide rate twice as high as police officers or the general public. The incident in Delaware is also likely to revive the debate about how prison authorities should respond to riots, a conversation which could get ugly.

“I think the criminal justice system is in big, big trouble. It is not a system. It is an industry. And it doesn’t work,” Mike Smith told me. “And this is maybe not an educated remark to make but you can’t put an animal in a cage and poke him with a stick and expect him to come out better than he was when you put him in there…. But it seems like our society prefers to forget. When you put a problem behind walls it is sort of as if society doesn’t have to look at it or acknowledge it until there is a riot. But as a society we have to make major changes to our criminal justice system and major changes in how we think.”