Begin the Descend

Hebrew has a verb to describe the act of a Jew immigrating to Israel: la'ahloht, “to ascend.” Upon deciding to leave Israel, our correspondent starts the slow process of descent well before boarding the plane.

“Boom,” goes the Israeli rocket. “Boom, boom,” goes the Hamas rocket. “Boom, boom.” “BOOOM.” “Forget this,” mumbles Annalise, hunting for her passport.

Advanced Hebrew

Hebrew has a specific verb to describe the act of a Jew immigrating to Israel: la’ahloht, “to ascend.” A Jew does not immigrate to Israel; a Jew ascends to Israel. And, of course, when you realize the experiment has ended or failed or is about to blow up the lab, you don’t just return back home. No, you descend back to your old life, leaving the enlightened peaks of Mount Zion and floating back down to the messy and venal world outside of Israel’s gates.

I moved to Israel in May 2011 looking for a change and a way to shake up my increasingly mundane life. Because I am half Jewish, Israel’s arms were wide open to me, and I was promised a future of beaches, boys, freedom, and falafels. Israel, largely, delivered. But two long summers, one Arab Spring, five rockets, and one bus bombing later, when faced with the decision to renew my work contract or move on, I have decided to move on.

Everything has a precipitating event. On Nov. 14, Israel assassinated Hamas leader Ahmed Jabari, which was a response to and an instigator of continued Hamas shelling of southern Israel, which itself led to subsequent Israeli air strikes on the Gaza Strip. As Israeli ground troops started to mass at Gaza’s borders and the number of casualties crept into the double digits, things took a serious turn, and I realized that 18 months into my Israel adventure, there was going to be a war.

Rocket No. 1

The first rocket fell on Tel Aviv on Nov. 15 as I was leaving work. All afternoon, the rockets had been falling closer and closer to Tel Aviv; first Sderot, then Ashdod, then Rishon LeZion (“Why, that’s where the IKEA is!” shrieked one colleague). After the IKEA rocket, I knew—just knew—that one was headed for Tel Aviv next, and so I decided to stick around the office, which is in a building with an impressive deep basement, rather than risk the five-minute walk back to my apartment building. I cleaned off my desk. Deleted old emails. Watered the plants on my windowsill. Straightened the books on my bookshelf, chased dust bunnies, and finally decided that enough was enough, I was heading home. As I walked down the hall to the stairway, a colleague shouted, “That’s the siren, go!”

Code Red

The Gaza Escalation or Operation Pillar of Defense or Operation Stones of Baked Clay or the Eight-Day War or just the events of Nov. 14-21—however you want to term it—is proof to me that Israeli military and homeland defense technology is stolen straight from Star Trek. An automated system of computers or Android phones or Cylons watches the Gaza Strip day and night for projectiles hurtling toward Israel. The Cylons automatically assess the type of missile, its speed, range, and direction, extrapolate where it is headed and where it is expected to land, and compare that to charts of populated regions of Israel. If the rocket is headed for a populated area, a “Code Red” alarm sounds in that area—and that area alone—advising residents to take cover. This all happens so fast that you get 15, 30, 60, or even 90 seconds (for Tel Aviv) to take cover before impact. Depending on the amount of adrenaline in your system—which is largely determined by whether this is your first or fourth rocket attack—those 90 seconds can last an hour as you panic and process and pant, or just about 90 seconds, as you close your laptop, pick up your bag, and calmly walk to the shelter.

For the first day of the war, I hunkered down in my apartment with the TV off and the windows open, all the better to hear the siren. By the third day, I was meeting friends for lunch at a sidewalk cafe and shopping for new yoga pants.

The defense system makes large-scale rocket attacks eminently manageable. It’s almost impossible to be more than a minute and a half from a building, house, or doorway in Tel Aviv. Ergo, you can more or less lead your regular life, keeping one ear alert for the siren and taking cover only if you need to. For the first day of the war, I hunkered down in my apartment, eating tuna fish from the pantry, with the TV off and the windows open, all the better to hear the siren. For the second day, I went over to a friend’s apartment, where we decided it was OK to risk diverting our attention to watch Star Wars on DVD since her building seemed a bit sturdier. By the third day, I was meeting friends for lunch at a sidewalk cafe and shopping for new yoga pants. Since moving to Israel, I had heard so much about how “real Israelis” can so blithely carry on in the face of war. I found myself adopting the same attitude, though I give most of the credit to the “Code Red” system and only a tiny bit to personal chutzpah.

Rockets No. 2, 3, 4, and Probably 5, But It Gets a Bit Hazy Here

The first rocket aimed at Tel Aviv crashed into the sea while I was running down the stairs to my office’s basement. I didn’t hear it crash down—just the wail of the sirens until they wound down and stopped. The second rocket fell, again into the sea, while I was shopping for the aforementioned yoga pants. When the siren blew that time, the shop owner hustled us all to the center of the store, pulled the metal gate down over the entrance, and was interrupted by the large “boom” of a rocket hitting the sea as he jokingly offered us coffee. The third rocket caught me baking muffins. I turned off the oven and hustled to my building’s stairway; I got about four flights down before I heard a dull, echoing thud—what could have been a door slamming, or a successful missile intercept. I kept running all the way down to my building’s basement bomb shelter to find that the only other people there were my American and Canadian neighbors. I have lost count now, but I do know that another siren caught me chatting online with a friend. I ran down three or four flights of stairs before figuring, “That’s enough steps,” and staying put there until I heard the “thunk” of an intercept.

U.S. Tax Dollars at Work

Iron Dome is a U.S. government-financed game-changer that is the definition of “bang for your buck.” Not content with just giving a heads-up that a rocket is on its way, Iron Dome uses computers probably from the future to send rockets into the air to blow up the other rockets ostensibly on their way to blow up Israelis. And it hits its target more than 80 percent of the time. Hamas can send as many rockets as it wants toward Israel; Iron Dome will just swat them out of the sky, at the cost of $100,000 per interceptor. Of the five times the siren went off in Tel Aviv—some sirens representing multi-missile barrages—only one rocket made a direct hit. There are two ways to know Iron Dome is working: by listening for the boom of a successful intercept, and by not dying.

The Bus Blows

By Nov. 21, a week into the war, things were getting pretty comfortable. The sirens and rocket attacks, while no less diminished from the first days, took a back seat to my Thanksgiving planning. Maybe all this isn’t so bad. Then a bus blew up.

One of the things I have learned in Israel is that events both major and minor can have unpredictable importance. Over the previous two years, there had been at least a dozen Hamas shelling attacks on southern Israel before the straw broke the camel’s back, the Israelis assassinated Hamas’s No. 2, and war broke out. Now, it’s obvious how everything led to rockets in Tel Aviv, but back in early November, there was no reason to think things would end up where they did. The opposite happened with the bus attack: We thought it was the turning point when everything would take an irreversible tumble downhill, but, instead, the impact was as limited as that of the explosion itself.

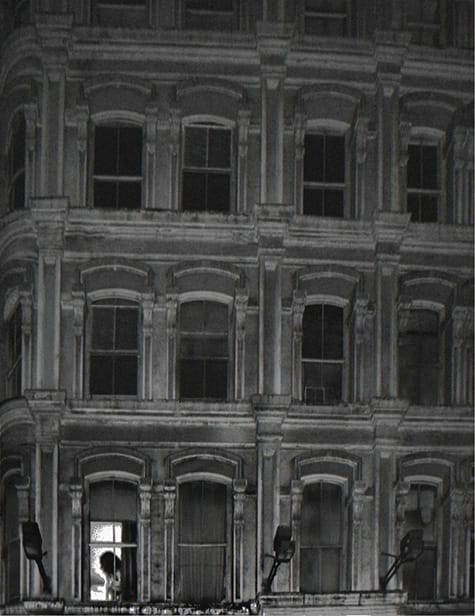

I noticed a group of people in front of a store, looking intently at the image of a smoking bus broadcast live from a kilometer across town. On the screen were images familiar to me from a decade ago, though at the time I was living across the world with no ties to Israel.

Now well acclimated to war, I was walking down the street, heading to the grocery store to replenish my canned tuna supply. I noticed a group of people gathered in front of a small convenience store, looking intently at the image of a smoking bus being broadcast live from just a kilometer across town. On the screen were images that were familiar to me from a decade ago, even though at the time I was living across the world with no ties to Israel: screaming ambulances, the long beards of the orthodox Jewish paramedics, shocked passengers covered in smoke and dust, victims being loaded onto stretchers, and police and journalists vying for control of the scene.

“Good lord,” I thought, and we thought. “Here it comes! The long-awaited Third Intifada: terror in the streets, fear, harassment, a return to the terrible times of the early 2000s, and a change that can never be undone.”

The Anti-Climax

Looking forward, we were facing nothing but a dark, dark path. Looking backward, this was the beginning of a neat end to the whole conflict. It wasn’t Hamas that blew up the bus, but West Bank sympathizers who crossed over the Israeli border to get a piece of the action. And they didn’t really “blow up” the bus, but more inexpertly took out a chunk of its middle. And they didn’t manage to kill anyone—or even hurt anyone severely. The terrorists were caught the next day.

Return to Normal

By then, Hillary Clinton had shuttled between Jerusalem, Ramallah, and Cairo and managed to broker a face-saving cease-fire. In just a few days, life had returned to normal. My colleagues called up for Israeli army reserve duty were back in the office after spending days on the border with Gaza, preparing for a ground invasion, and making elaborate plans for their now-free weekends. Drivers spent a day or two thinking twice before pulling up next to a bus at a stoplight, but traffic soon resumed its normal flow. Three months later, the border with Gaza is quieter than it has been in years.

I Can Do This

Israel escaped this one pretty much unscathed. It gave me a taste of what the conflict in the Middle East can dish out. While experts can debate where this was a mini-war or a “large-scale operation,” it was certainly something, and I weathered it fine. Weathered it quite well, in fact. Israel, a new job, different foods, a difficult language, armed conflict, and falling rockets: I can do this.

But That Doesn’t Mean I Will

When a job offer abroad came through a few weeks later, I accepted it without hesitation. Being able to handle life in Israel is one thing; actually wanting to do it is another.

I’ve settled into a nice life in Tel Aviv. I speak Hebrew well enough to socialize and get by. I’ve got friends and a go-to café and a favorite cashier at the grocery store. But I don’t want to settle here forever. Two years on, I have still not gotten comfortable with Israel’s narrative, nor do I see myself as a full-fledged part of its great experiment as a Jewish state. For one, there are too many extremists saying and doing things in the name of the nation that I could never agree with. I could lead a comfortable life surrounded by like-minded people in Israel, but I would be more or less restricted to Tel Aviv and its environs. And in a country of 8 million, limiting yourself to a city of 300,000 is a recipe for claustrophobia.

It’s not as simple as just not sharing the nation’s current rightward slant in politics. There are an equal—if not greater—number of right-wing fanatics, birthers, and gun nuts in the U.S., some of whom would make the average West Bank settler look like a Berkeley peace activist. I don’t give these types much thought, though; they’re just there in the background, part and parcel of the U.S. And that, I think, is the difference.

After two years in Israel, I realized that I’m a half-Jewish American, emphasis on the American. Despite our shared genes, despite our classification by the Third Reich, despite our dark hair and mild lactose intolerance, I have less in common with my Israeli neighbors than with your average Wal-Mart shopper. Maybe 27 is too late to start over in a new country, maybe my Jewish father didn’t teach me enough (OK, any) Sabbath songs, maybe I wasn’t looking hard enough for God in the cracks of the Western Wall. Or maybe I just missed marshmallows, Christmas, Sponge Bob, the Verizon Guy, Starbucks, customer service, and country music. Whatever it was, when push came to shove and buses became potential bombs, I felt no great need to seal my fate to that of the nation of Israel, whether victim, aggressor, or something in between. I decided it was time for me to start planning my slow descent as well. I found my passport and bought a plane ticket back to the homeland, where the rocket’s red glare remains a mere figure of speech.