We head to Cleveland for Thanksgiving to break bread and the news. On the flight, Patti and I discuss how little we are looking forward to another Thanksgiving and then another Christmas in Ohio. Not that we don’t love Ohio, or PL’s parents, cousins, uncles and aunts, etc. but it’s the same every year. The same food, the same weather, the same visits to Parmatown Mall, the same offhand racist remarks from her uncle-in-law. A few months earlier, we’d been fantasizing about going somewhere warm when Pipsi suggested we join her on the cruise to the Caribbean. Of course, this meant we risked offending Patti’s parents, Mickey and Phyl. So we invited them, too. Now, the whole mongrel pack will be on a boat for two weeks. PL and I have been wondering what on earth this motley crew will have to talk about at dinner every night.

In Cleveland, we break the news to Phyllis and she is nonchalant. Mickey is similarly nonplussed. When Aunt Jean stumbles upon PL’s copy of What to Expect and PL admits her condition, she is pretty ho-hum, too. Grammy Kiraly is pleased but never mentions it again. Maybe she is just too attached to her first great-grandson, our dog, “Mr. Frank,” as she calls him.

We are surprised and disappointed that nobody seems more blown away, but PL decides it was her flawed delivery of the news. My sister-in-law, Debbie, is a lot more psyched and says Mickey and Phyl had had similar reactions when she’d told them that she was pregnant with Morgan. Maybe this news is just more everyday and expected than we think.

I guess we hoped for all sorts of back-slapping and hugging and nuggets of wisdom but forgot we’re not on a sitcom. People just aren’t blown away by the fact that a young married couple is reproducing. Damn.

We call Gran in Jerusalem and tell him the news; he asks me if my chest is inflated and reminds me that if there is no room on the front that I could always pin some medals on the back. His way of saying he’s thrilled to be a great-grandfather, which he certainly seems to be. Odd, he’s the last one I thought would get all ferklempt.

Every time we go to Cleveland, we are struck by how much simpler life seems to be in the Midwest. People leave their work at the office. They have hobbies. They own their own homes, big modern houses with yards and cars, not the shoeboxes and subway passes of New York. Everything seems so safe, everyone seems so nice.

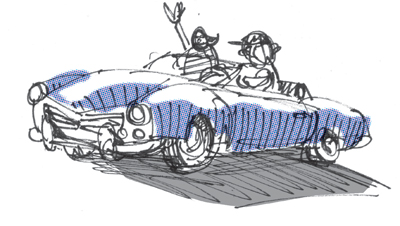

Mickey always has two cars, always GM, usually Buicks. Whenever he buys a new one, Phyllis inherits his old one and hers goes to the dealer. Patti and I volunteer to drive her grandmother home from Thanksgiving dinner and Mickey says, “Here, take the good one,” and hands me the key to his new car, a blue Riviera with a fake white canvas convertible top.

We drop Grammy at her little yellow house and visit briefly with her dog, Princess. On the day Grammy’s husband, Elmer, died, Princess appeared on her doorstep and the two have been inseparable ever since. Grammy cooks herself two eggs, bacon and toast for breakfast and Princess gets the same. She makes herself a Dagwood sandwich and pie for lunch, Princess gets the same. She has pot roast and boiled potatoes and homemade kraut for dinner, Princess gets the same. Princess is now a waddling 100-pound barrel of dog flesh.

On the way home, we pull up to a stop sign by the Jack Frost doughnut store. Suddenly, sickeningly, I feel a car crunch into the rear end of Mickey’s new Buick Riviera with the fake white canvas convertible top. Our car lurches forward; Patti yelps.

I sit there for a second, watching the car behind us in the rear-view mirror. It’s a gray autumn afternoon, dusk is falling, and the other car’s interior is dark.

I put the Buick in park, get out, and walk back to survey the damage. Red plastic shards litter the asphalt. The bumper is dented, the trunk is dinged.

The driver of the other car, a rusty Trans Am, slowly emerges. He is moving slowly, and I instinctively say, “Are you OK?”

He says, “Oh, shit, man. I’m so sorry. Shit.” He’s now close enough that I can smell the Jim Beam.

“Listen, listen, listen. Let me take care of this.”

“Uh, huh. Do you have a license, registration? This isn’t my car. It belongs to my father-in-law.”

“OK, OK, OK, listen.”

“Uh huh?”

“Listen. I got a friend who can take care of this. We don’t need no cops. I’ll take care of it.”

“Can I have your name?

“OK, OK. Hold on.” He grips on to the roof of his car then suddenly ducks inside again. I tense up. Is he planning to drive off, fleeing the scene? His door still open, he is rummaging around in the glove compartment. He comes out brandishing a matchbook and a pen. He leans on the roof again, writing.

“Excuse me. So what is your name?” I ask again. I’m not sure what to do with this guy. He’s wiry and tallish and has a lot of random energy. In spite of his guilt and intoxication, he’s the one controlling the situation.

He points approximately at his chest, then hands me the matchbook. “Bat…Masterson,” he says. “Call me.”

Then he climbs back into his car and drives around us, weaving away.

I pick up some of Mickey’s taillight off the ground and get back in the car.

“So what happened?” Patti asks.

“I dunno. He left.”

“I wrote down his plate number.”

“Well, that’s good, I guess. He gave me his phone number. Bat Masterson.”

“What?”

“He said his name was Bat Masterson.”

“Wasn’t that the cowboy?”

“Yeah, from TV.”

“My brother liked that show.”

We decide to go to the police. Partly to get a drunk off the streets, partly out of self-righteous indignation, mainly to cover our asses. We have no idea how to find a police station, having only a sketchy idea of where we are.

“We should stick to this road,” I say. “Otherwise we’ll have no idea how to get back to your parents’ house.”

Then we see a cop car, parked. I pull up behind it and get out. An officer is in the driver seat, and I approach his window.

“Excuse me, I was won…”

“Step away from the vehicle,” he barks.

“No, I’m just look…”

“Get away from my car,” he says, winding up his window.

“But…”

“Asshole, I have a prisoner in back. Move away.”

Now I see a figure bent down in the rear of the car.

“I’m just looking for a police station,” I yell through the glass.

He gestures violently with his hand, telling me to back away and, I think, to look further down the street.

Patti and I drive further down the street and then see the stationhouse.

Inside, a square lobby, empty except for two men, one covered with blood that seems to be coming from his head. Exchanging sidelong glances, Patti and I hurry to a metal window in the far wall. The window is covered with a steel door and surrounded by wanted posters. An electric buzzer bears a sign, “Ring for service.”

We ring several times. No service.

“They’ll come. Just wait.” It’s the bloody man.

We sit down just as an ambulance pulls up outside. Two EMT guys rush in with a tackle box full of equipment. They ask the bloody guy, “You the guy that’s hurt?”

“Yup.”

The medics start to bandage the guy’s head. All the while he talks rapidly. “Me and my buddy, we’re sitting at the light. Just sitting there. He’s driving, right. So, then, this car pulls up on the left, full of a buncha nigger kids, teenagers, kids. They’re blasting music. The light changes and they throw a brick at us, a fucking brick. It goes through the window, past my buddy here, and fucking hits me in the head. A brick. Look, I brought it in from the car.” He holds up a brick.

Just then another steel door opens in the corner and a policewoman steps out. She’s short, thick, a brick, lit from behind like a hero.

The bloody guy says, “Excuse me, officer?”

Instantly, the policewoman, puts her hand to her gun, unlatches her holster and half draws the weapon.

She says, “Did you call me ‘babe’?”

Immediately, all of us, the bloody guy, his pal, the medics, Patti and me, we all say, “No, no, he called you ‘officer,’” all vigorously shaking our heads.

She holsters her gun and says, “Wait here.” Then she steps back through the steel door and it locks behind her.

Patti and I look at each other, get up and leave.

Mickey is surprisingly unperturbed by the damage we’ve managed to do in one three-mile drive. He says, “Bat Masterson?”

My brother-in-law, smoking a Marlboro at the kitchen table, begins to sing in a deep voice:

“Back when the West was very young

There lived a man named Masterson

He wore a cane and derby hat

They called him Bat, Bat Masterson.”

Eager to resolve things, but sensing the futility, I dial the number on the matchbook.

It rings six times before an old woman answers.

I say, “I’m looking for Bat Masterson?”

“Bat?” she shrieks, “Bat?”

“I’m sorry. Yes, is there a ‘Bat’ there?”

“Bat? Bat?” Her voices rises with each “Bat?”

I hang up and shrug at Mickey and Phyl.

“Will your insurance cover it?”

“So in the legends of the West

One name stands out from all the rest

The man who had the fastest gun

They called him Bat, Bat Masterson.”

Mickey calls the number again the next day. The driver answers. He is a fireman and was afraid to have a DWI on his record—it would have cost him his job. His name: Pat Masterson. He’s never heard of the cowboy show. His friend, who has a body shop near the Parmatown Mall, restores the Buick, free of charge.

Despite the happy ending, Patti and I can’t wait to get back to New York, where it’s safe.

While PL is getting a manicure, I look up names in a book at the B. Dalton at the Parmatown Mall. We’ve talked about two names, both formerly owned by people now dead.

We already have three Jacks. Jack Waldman was a friend of Patti’s, a musician, who died just a month before PL and I met; she has always believed that he sent me to the party where I met her. (Actually, I took a cab.) Jack Buchanan is one of our favorite British actors, and, of course, the baby was conceived in an Atlantic City Jacuzzi.

Jack, it turns out, was a popular name until the 1920s and isn’t used much these days in America. It’s usually short for John or Jacob or Jake. It has noting to do with Frère Jacques. One book says the name means “God has been gracious” while another, ominously, defines it as “supplanter.”

The other name we’re considering, if the chromosomal coin flips the other way, used to belong to my grandmother. Kate was Ninny, my grandmother, whom I loved very much and who just passed away.

Ninny was always the same height as her husband. She came from tall stock—her brothers, Kurt and Ernst, were famously giant among the runts of Eastern Europe who fled to Palestine in the 1930s. Gran, however, is a small man with a large nose. When he turned 60, his nose and ears continued to grow while the rest of him got shorter. Then, when Alzheimer’s eraser was working on her brain, Ninny broke her hip and spent the little while she had left in a wheelchair. For once, Gran was taller.

When she was 18 and still Kate Neumann, she traveled to the fledgling Soviet Union, a girl, alone. It was uncharacteristically political of her but a daring, late 1920s sort of thing to do for a girl from the German bourgeoisie. Soon, her family was to learn that they weren’t in fact Germans, weren’t the integrated, beloved, liquor and bar supply salesmen they’d thought they’d been for generations. They were Jews and had a brief window of opportunity to flee.

While her parents and brothers sailed east to Jaffa, Kate enrolled in medical school at the University of Rome. She and her perfectly proportioned husband wound up in India, then in a British prison camp with two small children for six years.

Despite the deprivations and harshness of life in India, Ninny always maintained her poise. In time, she and Gran were eminent and successful, hosts to visiting dignitaries and film stars. She ran their laboratory and their adjoining home, an amazingly modern woman, completely self-invented.

She kept her mother and grandmother’s high standards alive in the dust of Lahore. She designed her own clothes, buying fabric in London and then giving precise direction to tailors who sewed cross-legged in the streets of the Anarkali bazaar. She laid out her garden like a Persian carpet and regularly won prizes for her roses and chrysanthemums. She loved music of all kinds and had Lahore’s most extensive and up-to-date LP collection on her gramophone. Occasionally she made simple, beautiful watercolors, usually landscapes. She loved Pakistan, too: loved the food, the history, the architecture, the craftsmanship, the mountains of Kashmir and Murray and Swat.

When I was two, she would sing a Urdu lullaby to me:

Ninny babaa Ninny,

Makhan rhoti cheenee.

Makhan rhoti hogyah,

Danny baba sogyah.

I began to call her Ninny.

Ninny was always the sweetest person in our family, the most sentimental and romantic. She would tell me stories, laugh at my jokes, show me beauty. The creative impulse that runs through Pipsi and then through me begins with her. Maybe in a different time and place, Kate would have been an artist. But her world was too pragmatic and difficult for such self-indulgence. She channeled her creativity into her hand-built life, full of surprising details that took enormous effort under the circumstances. I miss her, the way she was when I was small: gentle, fun, foreign, ladylike and very present. Gran was always an intellectual but Ninny loved things that were lovely.

If the baby is to be a girl, a little lady, I hope that she will have many of Ninny’s, of Kate’s qualities. According to the book, Kate is generally short for “Katherine,” which means “pure.” So both names, Jack and Kate, are both common and uncommon. Just fine.

Speaking of just fine, PL’s breasts are quite enormous and rock hard. Yow.