Around the World on 18 Plates

We asked people around the globe—in Uganda, Ecuador, Fiji, and more—to make food from the opposite side of Earth.

Uganda ✈ Mexico

by Avril Perry, Nuba Elamin, and Josephine Ndao

A Ugandan and a Liberian New Yorker let a Senegalese girl with a DC accent talk them into making Ensenada tacos in a kitchen outside Kampala. Two years after fate threw us together in Monrovia, we had gathered in Entebbe for a girls’ weekend. No one had mentioned that it would take two days to find the ingredients, and rightly so, for we would surely have done something else instead. We made four trips to the same Kenyan supermarket chain and several fruitless treks to local grocers. Ground coriander was abundant, but cilantro remained elusive. The word “tortilla” was predictably met with furrowed brows; once, a shopkeeper shuffled down an aisle and, hopeful, held out a bag of Doritos.

We were no ordinary ladies, however: We were ambitious and we were stubborn, so we boarded a boat floating on lily pads, determined to catch fish on Lake Victoria. The captain opened a bottle of red with a screwdriver as the trawlers dragged behind us. Halfway to our destination, we received a distress call from a stranded boat, so we sped back and towed the ingrates ashore. The sun was heavy in the evening sky when we reached the island on the equator; we watched the crew reel nothing in with their fancy poles while the local boy with a wooden switch caught fish after fish after fish. We conceded defeat and motored back to dry land in the dark, empty-handed. We bought frozen tilapia and fresh chicken, which Nuba marinated overnight.

Only as we began to cook on Sunday evening did we realize that this “fully stocked” kitchen had neither measuring cups nor an electric mixer. We charged ahead anyway and, armed with a Googled recipe, beat eight homemade tortillas out of a questionable lump of dough. But the previous day’s full bottle of vegetable oil was suddenly nowhere to be found, so we melted a tub of buttery spread, which, of course, boiled over in the microwave. Jo fried the tortillas with the gentleness of a new mom as rap played on a Mac; Nuba stirred half-frozen tomatoes into an overripe avocado; Avril took notes and thought about love and tap water.

We ate in the dark with a view of the lake from the upstairs terrace. In between bites, we swatted away tiny insects en route to the lantern. A guinea fowl and crickets competed in the background. The fish was flavorless and the guacamole lacked something unnamable. The chicken was mouth-watering but the tortillas crunched between our teeth. The kitchen, naturally, was a crime scene.

Thank goodness for white wine on a warm Uganda night.

India ✈ Peru

by Bethany Milton

Mumbai is not particularly known for global culinary diversity, so, I was not expecting to find food from our antipodal partner, Lima, Peru, in our fair, chaotic, star-struck, simultaneously under- and over-developed megalopolis of 20 million souls. But then I kind of did. Until I didn’t, in a very Mumbai story.

I have certainly never heard of a Peruvian restaurant in Mumbai. Or a Guatemalan one or a Brazilian one or an Ecuadorian one. There is one Mexican restaurant called Sancho’s; they offer paneer fajitas, chocolate nachos, and a decent frozen margarita. For most Indians, “foreign food” means Chinese (more correctly, Chinese foods adapted for Indian palates, which plays the same cultural role as Tex-Mex in the U.S.), pasta with red sauce, greasy pizza, or shawarma. With over 1 billion people and 17 extremely diverse states, it’s not surprising that Indians tend to stay within the subcontinent when it comes to culinary choices.

Just to double-check, though, I Googled “Mumbai Peruvian food.” And that’s when I found the Peruvian burger joint a 15-minute walk from my house.

Bembos is Peru’s homegrown McDonalds and has a menu heavy on hamburgers, chicken nuggets, and side salads, offered with Peru’s distinctive aji sauce and an option to swap your french fries for fried yucca. The chain was founded in 1988. Twenty or so years later, management decided it was time for international expansion, and India it was.

Eventually two- and three-star reviews are replaced by one-star reviews: There’s a mosquito infestation; the staff just stare mutely at customers.

Some focused Googling turns up a 2008 puff piece in Food Industry India, which credits three Indian businessmen with strong ties to Lima with bringing three outlets of the chain to Mumbai and New Delhi. Before heading off for my burger, I decided to check out Burrp, the Indian version of Yelp, to see what I was in for. The early reviews start out ecstatic, with customers relishing the big size and the quality of the burger, the unlimited free mayonnaise, and the novelty of getting fast food somewhere other than McDonalds. Their menu doesn’t show much of a Latin tinge—more of an Indian one, with a Hot Veggie Masala Meal Deal and a Chicken Tikka Combo—but it’s Peruvian enough for Mumbai.

Over time, though, the cracks start to show. Five-star reviews give way to four- and three-star reviews that complain about counter staff more engrossed in watching a cricket match on the TV than taking orders, soggy buns, and watery sauces. Eventually two- and three-star reviews are replaced by one-star reviews: There’s a mosquito infestation; the staff just stare mutely at customers, giving them the heebie-jeebies; the lettuce is both wilted and black. The latest review is titled “God awful.”

Nevertheless, I was not deterred. I was going to find Peruvian food in the Maximum City and here it was. I laced up my sneakers, put some money in my pocket, and thought to double-check the location with my husband, who has lived in our neighborhood far longer than I have.

“Wait, you mean that dirty burger place? The one that closed down a few years ago?”

I guess after one-star reviews in a city that was never particularly fascinated with foreign food, there’s nowhere to go but out of business.

Ecuador ✈ Malaysia

by Camilo Kohn

Today I cooked Malaysian food for the first time.

Today, I think I tried Malaysian food for the first time.

Laksa asam is a traditional Peranaka spicy fish soup usually served for lunch. Peranaka cuisine is a fusion of Malay and Chinese culinary traditions, and from what I can tell it is damn spicy!

On my shopping list were things like rice noodles, Makrut lime, tamarind paste, bird’s eye chiles, ginger, turmeric, shrimp paste, and the list went on.

Of course, living in Ecuador hampered my ability to do one of my favorite things: cross stuff off a list. I couldn’t find half of the things I needed.

Things have changed a lot in the past years and immigration to Ecuador has exploded, but still, even at my Asian store I couldn’t find dried shrimp, candlenuts or galangal.

Luckily I managed to get enough ingredients to keep me motivated.

With a bag full of chiles, fermented stuff, and a giant head from a proud sea bass, I headed home and got the ball rolling.

First order of business: Make the spicy, eye-burning, tear-dropping, jaw-quenching paste that will be the base for the soup. Sauté it up with some shrimp paste, add some water, the seasoned bass head, and a ridiculous amount of acid, and you basically have your soup.

Now, one thing is to have a flavorful broth, another is to have a laksa asam developing in your pot.

I’m not sure if I achieved this, but I went with it anyway.

I took all the meat from the cooked head and returned it to the pot, I adjusted the seasoning like a pro, and I ended up with the spiciest broth I have ever had, ever.

I was cooking this for my parents so I wasn’t sure if I should even serve it.

It tasted good, really good, actually, but it was so freaking spicy that I knew I was going to see my mom cry at the table.

The complete dish consists of a base of rice noodles covered with this broth and topped with an array of herbs and veggies. So I figured I still had hope to make it work.

My parents sat at the table and in front of them I placed an innocent-looking pot with a garden on top. Cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, mint, red onion, halved limes, and cilantro decorated the liquid fire.

I sat anxiously watching as my parents took their first spoonfuls. Would they scream for water? Would they spit on the table?

Once the initial shock of gulping down piping hot, mad spicy broth was over, they said they liked it! They really liked it. They thought it was way spicy, but they managed.

I went ahead and tried it myself, a big spoonful with all the goods inside, and it was pretty damn good! Even though the broth itself was hot hot hot, the combination of the noodles and all the fresh toppings made of this Ecuadorean Laksa Asam a real winner.

South Korea ✈ Argentina

by Alice Rhee

When I first heard of Argentina’s coastal city Mar del Plata, I was taken by its name (or my mistranslation thereof)—“Sea of the Plate.” I pictured a whale-sized plate of Argentinean food cruising the waves, scattering sunlight and the errant empanda. Photos of the city’s (plate-free) beaches radiate vitamin D. But in gray, icy Seoul, the only radiation I’m getting is from my computer screen. Mar del Plata seems a world apart from my current reality, for good reason: It’s literally the farthest city in the world from Seoul, South Korea. Instead of blowing five grand to fly for 37 hours, I chose the next reliable way to transport myself to Mar del Plata. I would have an Argentinean meal.

Asado, or barbeque, is practically Argentina’s national emblem. Reading up on Argentinian cuisine, however, revealed unexpected cross-cultural seasonings. Pizza and pasta dishes are daily staples, carried over from Italian immigrants during the mid-1800s. One such pizza dish is fugazza. Its thick, focaccia-like crust is topped with melted mozzarella and onions.

I remembered I had leftover pizza. This cheese pie, from a Korean chain, came without red sauce (while inexplicably including cream cheese in its four-cheese blend), and its crust approximated the thickness of focaccia. It was a weird pizza. But where the details slipped in accuracy, my timing was perfect. Seoul and Mar del Plata are exactly 12 hours apart. With every bite, I wasn’t indulging in a midnight snack. Rather, it was noon in Mar del Plata, and I was experiencing their lunchtime, with them. It wasn’t delicious, and it didn’t give me a tan. But never was a late-night slice so justified.

To reach Mar del Plata transcendence, my eye was on asado. The only Argentinean restaurant in Seoul is in Gangnam, which means it’s expensive, and time-consuming for me to reach. Korean barbecue restaurants, however, are on every street. Outside of Korea, Korean BBQ is typically associated with thin cuts of marinated meat. Deungshim-style, however, focuses on thick, quality cuts of plain sirloin steak. And what does asado call for? Among other meats, un-marinated steak, cooked over charcoal. In fact, there’s a charcoal deungshim place right down the street. Necessity is the mother of invention, but laziness deserves some credit, too.

Great steak is universal, but for true Mar del Plata flavor, I blended a bright green chimichurri sauce to accompany the “asado.” Parsley and cilantro give it its color; olive oil, garlic, vinegar, and onion round out its flavor. I snuck my smuggled container of sauce onto the table. It looked at home amid the green leaves and soju bottles. Bypassing the ssamjang, I dunked a cube of steak into the chimichurri. It felt surreal, to take in the unfamiliar flavor in the very familiar setting. My synapses lit up like fireworks from mouth to memory, like the kind they might shoot off the beaches of Mar del Plata, sparks soaring toward the horizon in the direction of the other side of the world.

Fiji ✈ Burkina Faso

by Brooke Yamakoshi

To be rich in a poor country is to be at the top of both the metaphorical and literal food chains. Carnivore restaurant in Nairobi may be the most literal, where tourists, aid workers, and businessmen feast on all-you-can-eat kudu, crocodile, and ostrich served churrasco-style by waiters wearing boater hats and zebra-striped aprons.

From my privileged perch as a aid worker in Suva, Fiji, my relative wealth is more likely to be spent on imported yuppie comfort food like almonds, quinoa, and—yes—kale, than exotic game (though perhaps this isn’t much of a reprieve, given Fiji has only six native mammals, all of which are bats).

Cooking food from a rich country in a poor country is sometimes difficult and usually expensive. Stripped of the usual kitchen arsenal but armed with increasingly-valuable US dollars, we usually manage just fine—though we’ll still gladly bitch about our hardship.

In contrast, cooking food from one poor country in another poor country is easier. Even when those two poor countries happen to be separated by over 19,000 kilometers, or, apparently, 43 hours of flying. Peter Menzel and Faith D’Aluisio’s 2006 book Hungry Planet presented the inequities of global food distribution and rich variety of cuisine through photos and essays from a range of 30 countries, but a similar book with examples from only developing countries may show greater homogeneity.

In perusing Burkinabé recipe options online, I settled on the easy-to-source and impossible-to-fuck-up recipes of riz gras and gombo.

Fiji is a tiny country of 800,000 living on a few tropical islands adrift in the Pacific Ocean that suffers from seasonal cyclones and random tsunamis. Burkina Faso is a small, land-locked, Sahelian country that suffers from seasonal dust storms. Both suffer from high transport costs, a history of coups d’états, and a changing climate. But both have seasonal abundances of okra, tomatoes, greens, cassava, onions, bananas, plantains, avocados, mangos, papayas, and coconuts, which was plenty of fodder for my culinary homework.

In perusing Burkinabé recipe options online, I settled on the easy-to-source and impossible-to-fuck-up recipes of riz gras and gombo. I skipped any recipe that called for millet, since why would a poor country import a bland staple crop from faraway poor countries when they have their own bland staples, like taro and kumara? Riz gras calls for goat, onion, tomato, cabbage, carrot, rice, and a cube of the ubiquitous Maggi bouillon. The gombo recipe that I was nominally following called for okra, tomato, onion, garlic, greens, and beef, with palm oil and spices.

My online searches taught me that, in Burkinabé cuisine, “attention to detail is important” and “each traditional dish has a special cooking method.” Ignorant of the important details, special methods, and familiarity with the final product, cooking was easy, and I soon had two one-pot meals that smelled and tasted good enough to share.

Any one-pot meal is bound to be hearty, comfort-food style. Both dishes were satisfying but not particularly exciting, since neither of my recipes had called for spices beyond chile. Similarly, traditional Fijian cuisine features fresh ingredients simply and plainly prepared, given the historical lack of spices. The forced migration of laborers from India during British colonial rule brought new food crops and spices, as did later migration from elsewhere in Asia and around the world.

The leftover riz gras came with us to Nananu-i-ra island over the weekend and was eaten as a side dish to lunchtime chicken and tuna wraps. No one was impressed or surprised when I explained that it was a recipe from Burkina Faso; we’d been for a long hike, and it had steak in it. After all, was it any more or less exotic or unexpected than our tuna tataki or chana masala dinners?

South Africa ✈ Hawaii, USA

by Margaret Ann Mazzenga

I live in Pretoria, South Africa, where traditional food consists of meat, meat and more meat; oh and some Pap, a thickened porridge made from finely ground corn. South Africans celebrate special events or just a regular Saturday with a Braai, barbecuing lamb, beef, boerewors (sausage) on wood logs. The word braai in Afrikaans means “grilling meat” and South Africans are very proud of the fact that they do not use gas grills to cook their meat. Nineteen thousand miles away from Pretoria is the island of Honolulu, Hawaii. While Hawaii and Pretoria are extremely far apart and different in so many ways, I was interested in finding their similarities when it comes to food. Hawaiians, like South Africans, experience mostly mild temperatures year round (also depending on where they live in Hawaii). They also take advantage of the beautiful weather and hold a traditional barbeque called a luau. Furthermore, Hawaiians do not use a gas grill, either. They cook their pigs on burning wood in an underground pit called an imu.

Hawaiians have some interesting and unique traditional foods. They use a root vegetable called taro, which they mash to make poi to eat alone or on seafood such as tuna. I was also surprised to find out that Spam, a Hormel canned meat product, is extremely popular. Hawaiians are the second-largest consumers of Spam in the world, second only to South Korea! Unfortunately Spam and taro are not readily available, and after some deliberation, I decided on a slightly westernized Hawaiian meal: pineapple barbecue chicken to pay tribute to the pineapple industry, and Portuguese sweet bread honoring the Portuguese ancestors.

To prepare my meal, I went out in search of pretty basic ingredients: pineapple, chicken, and green peppers, as well as some basic bread ingredients such as flour, butter, and eggs. Most I easily found at the grocery store. I was excited to use South Africa’s delicious pineapple, much better than the oversize fruits imported into America. I had a hard time finding the recipe’s barbecue sauce with “Hawaiian flavors;” I ended up choosing Woolworth’s Chinese barbecue sauce, which was actually perfect as present-day Hawaiians use many Asian spices, teriyaki being a favorite. The sesame and soy flavors of this sauce went well with the sweet flavor of the pineapple. I am not sure if I actually made a Hawaiian dish, but it was delicious. The Portuguese sweet bread was also divine—a cakey, spongy consistency with a sweet almond taste that reminded my husband of Italian Easter bread. I would recommend both dishes, but especially the sweet bread.

Pakistan ✈ Chile

by Hammad Umer

I took up this challenge with a slight hint of apprehension, stemming from the knowledge that I would probably end up paired with a South American meal, a cuisine that is almost unheard of in Pakistan. However, the aspiring chef inside me could not resist, and I soon found myself googling Chilean recipes. After much consultation with my wife, Ruquia, we settled on beef empanadas and pastel de jaibas (crab casserole) accompanied by pebre, a cilantro salsa. With the menu set, we decided to cook on the weekend when my friend Wei Wei would be visiting us from India.

Luckily, a lot of the ingredients used in Chilean cuisine are common and indigenous to Pakistan and hence were easily sourced. The blue crabs, however, were a bit tricky and had to be ordered a day in advance from the fishery and collected from a confused delivery guy at the corner of a petrol station.

With Wei Wei and Ruquia as my sous chefs, friend Sawera on line duty and her husband, Badar, on guitars (don’t ask), we set off on our six-hour Chilean journey. Lots of heat and hard work, a burnt thumb and various small cuts and scrapes were all punctuated with Badar’s acoustic guitar serenading, and come 1 a.m., our Chilean delights were ready.

We started off with the tempting empanadas with their beef and olive filling and that gorgeous crust. The salsa had developed a depth of flavor that perfectly complemented the empanadas, and both were devoured in no time. It is amazing how we use many of the same ingredients in our local cooking and end up with such different flavors. The pastel de jaibas was a soothing warm end to the tiring day we all had, the sweetness of the meat contrasting with the strength of the matured gouda. Unlike Pakistani cuisine, Chilean food does not seem to have much gravy, but if I were to compare flavors, I would say that it’s the perfect blend of Pakistani and Continental food. In fact, the salsa is pretty close in flavor to a chutney that my mum makes regularly at home. I’d be surprised if Chilean food doesn’t make its way into Pakistani restaurants in the near future; it’s definitely something I would explore more of.

Come to think of it, I was introduced to this challenge by a colleague in New York whose friend was looking for a participant in Guatemala. I would never have imagined having Chilean food in Karachi with a British Pakistani, an Australian Pakistani, and a Chinese-Taiwanese American who was visiting from India. If all these diverse palates loved the food, it has to be delicious.

California, USA ✈ Afghanistan

by Alissa Greenberg

The word “Afghanistan” is so inextricably tangled up with war, fear, and guilt in the American psyche that it wasn’t until I got this assignment that I realized how little I knew about daily life in the country. Breakfast has always been my favorite meal, and seemed a good place to start.

Feeling ambitious, I decided to tackle two recipes. First, roat, a sweetbread stuffed with apples and walnuts. The second was tukhum bojan, lightly fried eggs on a base of tomatoes, scallions, and cilantro. Both would have a unique California twist care of the ingredients I bought at Berkeley Bowl, a beloved Bay Area market famed for its spices and huge selection of produce.

The first steps of roat preparation felt similar to any other baked good. But there’s not much like opening a baggie of cardamom to remind you that you are not making chocolate-chip cookies. For a moment it was easy to understand the European explorers’ obsession with spices: Cardamom and its ilk were an instant, insistent trip to somewhere they’d never been before.

I’m no conquistador, but I did add my own special something to the roat preparation process: a Spotify playlist of French jazz, Colombian pop, and Persian electronica. After a while, I switched to an episode of NPR’s Wait Wait, Don’t Tell Me. I licked the mixing bowl while watching Gilmore Girls. I am undeniably a product of my environment.

As the roat baked, the aroma of cardamom-infused pastry filled my apartment, giving Rory and Lorelai’s antics a hint of Afghan flare. I imagined the same scent—warm and sweet and just a little medicinal—permeating other homes, very far away.

Cooking the tukhum bojan intensified that feeling of connection. I’m Jewish, and the dish reminded me intensely of shakshuka, a meal I’ve enjoyed during visits to Israel. The simplicity of the recipe’s instructions—sauté scallions, cook down tomatoes, crack eggs—left me time to reflect on how, geopolitics, tragedy, and endless conflict aside, the culture of that part of the world is closely linked to Central Asia. In some small way, preparing the tukhum bojan felt like meeting a distant cousin.

I invited a friend over, and together we admired the rich golden roat, studded with seeds and hunks of apple, and the bold primary colors of the tukhum bojan. While we ate, I thought about mothers preparing these dishes early in the morning in crowded Kabul high-rises; sisters and brothers hunched over fires in Hindu Kush villages waiting for that perfect golden crust; fathers cracking eggs over tomato in Queens apartments. I thought about how unlikely they all would be to watch Gilmore Girls while waiting for their bread to bake—but how, perhaps, they might lick the mixing bowl, sneak pieces of fresh tomato, or eat the results in the morning sun.

Thailand ✈ Ecuador

by Sara Lehman

While Ecuador is not technically the furthest country from Thailand (that would be Peru, but that option was already taken), it did offer a more formidable challenge than Peru in terms of finding locally available Ecuadorian food in Bangkok. Bangkok is a major Southeast Asia metropolis with restaurants to cater to just about all tastes and enough expats to support the import of things like quinoa, avocados, and all sorts of cheese. There is even an upscale restaurant serving Nikkei cuisine (Peruvian-Japanese fusion). However, the city has yet to open a dedicated Ecuadorian restaurant, so I decided to try my hand at making a common Ecuadorian dish (so says Google) of llapingachos, or potato pancakes stuffed with cheese. Anything stuffed with cheese is a win in my book. Llapingachos are fairly simple spiced potato-onion pancakes stuffed with cheese, so it oozes from the middle when you cut into it. It can be eaten with a peanut sauce called salsa de mani, fried egg or sliced avocado.

Since it was a Sunday morning and I was feeling lazy, I tried to make my llapingachos with the ingredients I had on hand. The result wasn’t bad—how can you go wrong with cheese-stuffed anything, really—but probably requires some refining for the flavors to truly work. For the base, I mashed three medium potatoes with two slightly ripe bananas from our garden, and added some cooked sweet corn kernels. As a vegetarian, I’m always looking for ways to incorporate more veggies into what I eat.

Cheese has only been widely available in Thailand over the last 50 to 60 years and for the most part, local taste buds happily avoid it.

If you are thinking what the heck is she doing mixing bananas and cheese, let me explain. Cheese has only been widely available in Thailand over the last 50 to 60 years and for the most part, local taste buds happily avoid it, especially the stinky, moldy, blue variety. (Thais’ attitude about blue cheeses is on par with most Westerners’ attitude about durian fruit.) That said, a common snack that many Thais grow up with is sliced cheese atop ripe banana slices. It’s so common, in fact, that a local ice cream chain offers a popular banana-cheese flavor. Hence, my inspiration for this attempt at fusion food.

The bananas softened the pancakes so it was difficult to get a firm, flavorful crust on the patties. I may have also been a bit impatient to try these and didn’t let them sit long enough. However, the cheese still oozed from the middle and made up for it. The bananas made the pancakes denser and very filling. I paired the pancakes with a salad of tomatoes, corn, and avocado, which was more than enough.

Next time around, I’ll probably reduce the recipe to one banana, omit the corn kernels (which made it more difficult to tuck the cheese in), and add more spices. Achiote power or paste could not be found in my neighborhood supermarket, which normally offers hard-to-find imported goods. I would make these llapingachos topped with a fried egg for a hearty breakfast, but otherwise, I will have to wait for Bangkok’s first Ecuadorian restaurant to try the real deal.

England ✈ New Zealand

by Giles Turnbull

A cursory glance at the web tells me that New Zealanders enjoy a nice plate of fish and chips, and that makes me happy because I am already on my way to the fish and chip shop. It’s early evening in January and it’s cold and windy, and I’ve had one of those days at work and my son has had one of those days at school, so we’re going to the fish and chip shop.

I won’t feel better for having had fish and chips. I shall feel fuller, and greasier, and guiltier, but not better. Fish and chips works best on a chilly evening in late summer, when you’ve spent a day at the beach without really eating properly. You’ve been in and out of the waves with your offspring, you’ve been building sandcastles and throwing a frisbee around. That’s the perfect fish and chips moment. That’s when all the fat and all the grease and all the vinegar create the perfect payload of carbohydrate lusciousness.

Fish and chips won’t have quite the same effect tonight, but we’re too tired to cook or to think so it will have to do. We queue up at the counter to place our order. Right at the last moment, the lad changes his mind and asks for a burger. A large one.

“Well that’s not very New Zealand,” I say.

“Do we all have to do the New Zealand thing, or just you?” he asks me.

I give him an evasive look and he answers for me: “No, it’s just you, because you write for The Morning News and I don’t. And I fancy a burger. Please.”

So he gets his burger and I get my fish and chips and we go home and eat them hurriedly before they get cold. Grease drips out of the burger and onto his school jumper. I drop chips from my plate on to my jeans. We slurp our fizzy drinks. This meal is a disaster for my waistline-reduction plan and for his teeth.

“We should go there, Dad, and see what the fish and chips are really like.”

“That was horrible,” I say at the end, wiping grease from the corners of my mouth. “I bet they make nicer fish and chips in New Zealand.”

The boy belches and nods.

“We should go there, Dad, and see what the fish and chips are really like.”

And that’s the best moment of the evening, because he’s absolutely right. I’m never going to know and understand New Zealand fish and chips until I’ve been there, spent that day on the beach down there, and bought some authentic local fish and chips. I imagine those would be the ideal fish and chip circumstances.

I grab my laptop for another cursory glance at the web—this time for flights. It’s a long journey. By the time I get there, I’ll be hungry.

Colombia ✈ Indonesia

by Kelly Connolly

After six months of living in Colombia and conscientiously devoting myself to the specialties of my region, I know my way around. Give me lechona, tamales, ajiaco, arepas—I love it all and can even cook some of it on my own. Indonesian food, however, was uncharted territory. In fact, I knew so little about Indonesian food that I couldn’t name a single dish. So I started with Wikipedia. I figured I would see if some main ingredients were also widely available here in Colombia and go from there. Indonesia is a country of thousands of islands with hundreds of indigenous groups and “one of the most vibrant and colorful cuisines in the world, full of intense flavor.” Right away we had some crossover hits: rice, banana leaves, peanuts, chicken, beef, coconut, green onions, lemongrass. Perfect. I found a recipe for a simple coconut curry. Not every ingredient was going to be available, but I never follow a recipe exactly, and since I didn’t know what it was supposed to taste like, I figured it would be all right.

For my ingredients I went to the plaza, an outdoor market with about 100 small stalls selling fresh food every day. Shopping there is always a challenge for me, exciting and intimidating. It’s the kind of market with dirt floors and buzzing flies, whole animals in various states of butchery, fruits and veggies I can’t identify. The food is the freshest and the prices are the best. I also like being able to talk to people, ask how different ingredients are prepared and where they come from. Most people are friendly and helpful; foreigners are rare in this part of the country and I am a novelty.

Bargaining is an unofficial national sport in Colombia. Even outside of the plaza many surprising things don’t come with a price tag, like bus tickets.

But then comes the purchase, and that’s the tough part. Bargaining is an unofficial national sport in Colombia. Even outside of the plaza many surprising things don’t come with a price tag, like bus tickets. You have to negotiate, always. It has taken me months just to develop an idea about how much things should cost. Add the fact that the food is measured in kilos and the currency is measured in thousands, and it can turn into a nightmare. Whenever I get back from shopping on my own, my boyfriend and his family always want to look over what I have bought and ask how much I paid. It feels like a kind of test, exhilarating when I succeed, embarrassing when I fail, and either outcome always seeming somewhat undeserved.

Finally coming back to do the cooking is the best part. I pick a Sunday afternoon when there’s nothing else going on and I can concentrate. Once in the kitchen I feel in control, confident and relaxed. Chopping onions and tomatoes, browning the chicken, measuring out the spices, seeing these familiar ingredients coming together in another, completely different way. When we sit down to eat, the food is delicious. Does it taste like Indonesian food? We don’t know, but that gives me plenty of room to call it a success.

Australia ✈ Morocco

by Ben and Candice Kortlever

Late on a Saturday evening, we visited a Moroccan restaurant called Sahara in downtown Melbourne. The menu offered soups, brochettes, grilled meats, tagines (a traditional slow-cooked stew), an assortment of tapas-style dishes, and a few different varieties of couscous. Our options at restaurants can be a bit limited, as I am a pescetarian, and Ben doesn’t like nuts in his food, but we had no problem finding enough dishes to suit us both. We decided to order a few of the tapas—vegetarian kibbeh, asilah-spiced calamari, and el jajida eggplant—with a small side of couscous. (We also tried to order the baked pastille pie, but it wasn’t available without nuts.)

Our favorite dish was the asilah-spiced calamari. Thick slices of squid were seasoned with Moroccan flour and served with a creamy lemon aoli dip. We’re both big fans of thicker calamari (as opposed to thin, circular slices), and we really enjoyed the intense flavor and satisfying texture.

Vegetarian kibbeh is very similar to falafel, but with lentils instead of chickpeas. The flavor is mild, but hearty; they had an almost crunchy exterior, with a softer middle made up of burghal, pumpkin, cumin and paprika spiced green lentils, served with a mint yogurt dip.

The el jajida eggplant was definitely the most unique dish in terms of flavor and preparation. Char-grilled cubes of eggplant were soaked in a citrus vinaigrette, seasoned with rosemary, thyme, and garlic. It was served a bit lukewarm, but it may have tasted better hot. The side of couscous was dry and light, steamed with herbs, large pieces of apricot and prune, and cranberries that provided a lovely fruity explosion with each bite.

Germany ✈ Tonga

by Sam Clapp

On a cold, bright January day, I set out into Munich to buy provisions for a Tongan feast. The farthest place on earth from southern Germany is actually New Zealand. But New Zealand is the farthest place from a lot of other places, and had already been claimed by another writer. So, armed with Google Maps and Wikipedia, I hopped around the South Pacific looking for other possibilities. I eventually landed on Tonga, which has some distinct culinary traditions and is far enough away from Munich that the most direct route between the two locations takes you over the North Pole.

For my Tongan feast, I ended up making two dishes: ota ika, a kind of “Tongan ceviche,” and lu pulu, consisting of meat wrapped in taro and banana leaves and cooked in a kind of outdoor oven dug into the ground. The ota ika was quite straightforward—all it required was a bunch of vegetables, lemon juice, coconut milk, and any kind of fish or seafood. (After getting intimidated by some whole fish in a fancy fish store, I went with some frozen Meeresfrüchte from the grocery store.) The lu pulu required a little more creativity. For the banana leaves I substituted tinfoil, as the purpose of these is just to hold everything together while it cooks. After a search for taro leaves in an Asian grocery store, followed by a search for spinach in a conventional German grocery store, I ended up settling for large leaves of romaine lettuce. The meat portion is usually a kind of canned corned beef that comes from New Zealand, but the stores here, despite the Germans’ fondness for meat products, did not appear to carry it, so I opted for hamburger. The final substitution was using my conventional oven in place of the outdoor, in-ground type, as I think I would have been waiting quite a while for anything to cook in the ground in Bavaria in January.

I normally never serve something to guests that I’m making for the first time. As the point of this exercise was culinary adventure, I broke that rule, but hedged my bets by having my Finnish colleague, Marko, over for dinner after he’d spent the whole day cross-country skiing and thus would be hungry for nearly anything. This menu actually proved ideal for entertaining, as the lu pulu needed to bake for two hours, and so could be made ahead of time, while the ota ika took only as long to make as it did to chop the vegetables.

Overall, the meal was surprisingly successful. The lu pulu actually reminded me of midcentury American “Polynesian” cuisine, owing mostly to my use of hamburger, but it was hearty and filling and good winter eating. The ota ika had subtler flavors, but tasted more like a summer dish, with the lemon juice and raw vegetables. I’d love to try it again in warmer weather and with more carefully chosen seafood.

Iowa, USA, ✈ Australia

by Emma Winsor Wood

As a vegetarian and East Coast transplant, I am out of my element in Iowa City, Iowa, birthplace of the “loose meat sandwich.” Meat and potatoes, in all of their forms, dominate the menus of most restaurants and good ethnic food is spoken of in hushed, reverent tones. Most nights I stay in and eat apples with peanut butter. It turns out I had to seek out a cuisine halfway around the world in order to eat like an Iowan.

“Meat and three veg,” the British equivalent of “meat and potatoes,” rests at the core of traditional Australian cuisine, alongside “bush tucker,” the Aboriginal hunter-gatherer diet, Vegemite, Melba toast, and “fairy bread,” buttered toast coated with rainbow sprinkles. Hours of perusing savory vegetarian recipes on Australian cooking sites yielded little that seemed definitively un-American: stir fry, lentil soup, spaghetti. Boring, boring, boring.

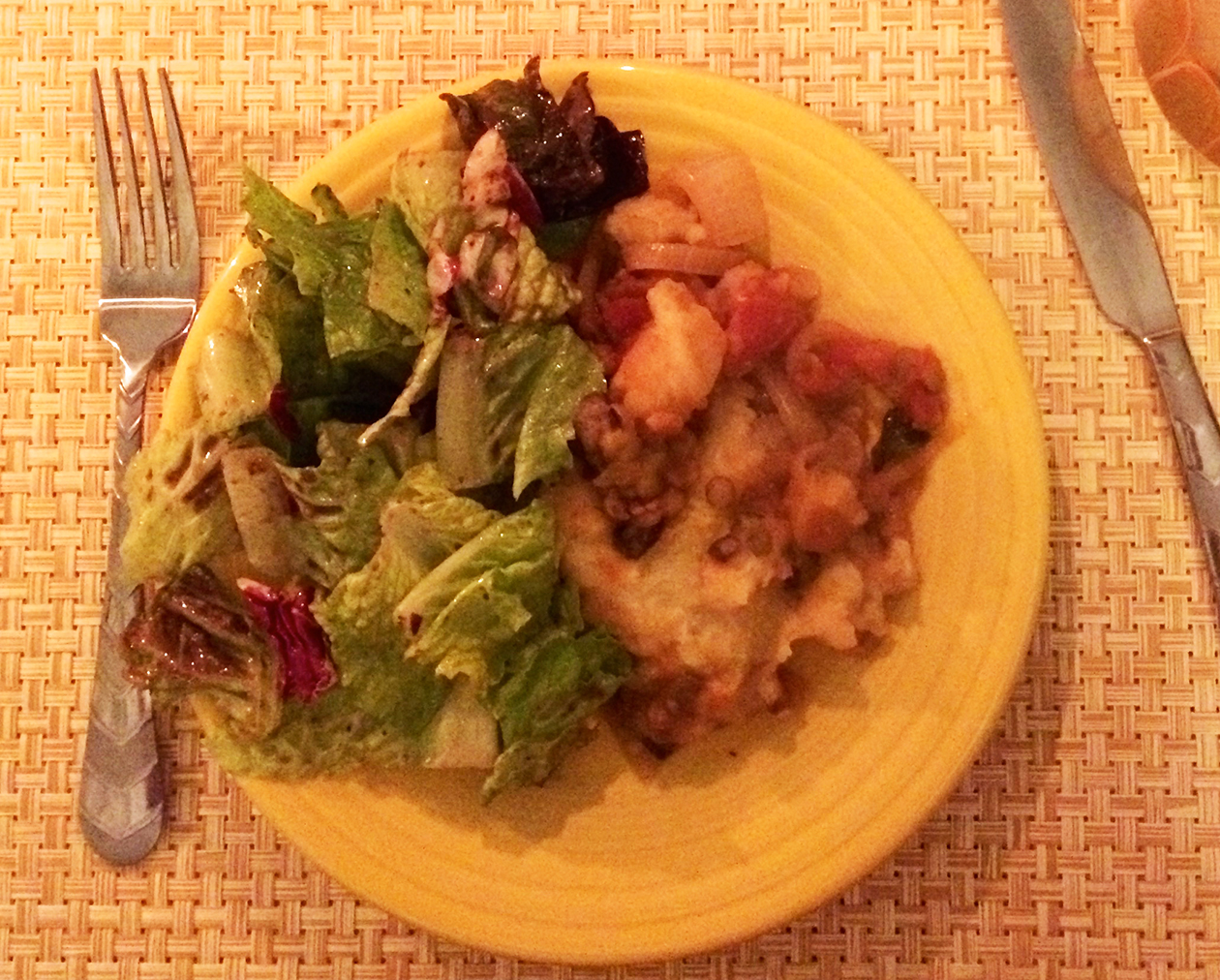

All roads led back to the meat pie, a holdover from Australia’s days as a British penal colony. Although the meat pie might not seem “exotic” to the Midwestern population, for me, as a carb-fearing citizen with a slight allergy to so-called “comfort food,” it was. I decided to make a vegetarian take on the British/Australian classic: a lentil-and-mushroom shepherd’s pie with a side salad. For dessert, we’d have traditional cakes called lamingtons.

Like many vegetarian recipes, the shepherd’s pie wasn’t difficult, but did involve many steps: Boil lentils; chop and sauté carrots, onions, mushrooms, garlic; peel, dice, boil then mash the potatoes, etc. The lentil stew resembled sewage. Fortunately I’ve learned not to judge by appearances with regard to food. I spooned the lentil mixture into a square ovenproof dish, then, instead of elegantly piping the whipped potato crust with a pastry bag as directed, I simply flattened the mashed potatoes over the top in a single lumpy layer before putting it into the preheated even.

20 minutes later, as my boyfriend, Conner, and I were enjoying the universal vodka-soda, something started to smell too pungent. I returned to the kitchen and opened the oven to find—beep, beep—the lentil filling had—beep, beep—overflowed its container and dripped onto—beep, beep—the oven floor, where it was hardening into—beep, beep—a blackened layer, setting the smoke alarm off. Conner waved a kitchen towel in front of the alarm, while I positioned a baking tray beneath the full dish. Crisis averted.

About 10 minutes later, we were eating. To my surprise, it was delicious. The lentil-mushroom mix had a subtle and smoky flavor that actually tasted like meat to my vegetarian tongue. We both had seconds.

After dinner, we made dessert in an assembly line: I dipped squares of the sponge cake I’d baked earlier that afternoon into a tub of runny chocolate icing while Conner rolled them in a bowl of coconut flakes before setting them to dry on a rack above a newspaper drop cloth. We ate them, still slightly warm, with store-bought whipped cream. I’ve been snacking on them all week.

New York, USA ✈ Russia

by Nikkitha Bakshani

The farthest city from New York is technically Perth, Australia, but cities in Australia are the farthest away from a lot of places, and Australia was taken. I was told to choose another country. Singapore? Taken. The UK? I hesitated. I was excited at the prospect of high tea, but as a lifelong anglophile, the option just seemed too easy. Russia! Russia is far away! Russians drink tea!

As soon as I sent a Russian tea party invitation to all of my friends, I realized I could have just taken a train to Brighton Beach. Alas. I skimmed the menus of various Russian restaurants and noted the items I liked: sturgeon, blintzes, vodka. My menu was set.

Sturgeon, a scaleless fish, is not kosher, but it is tolerated by many conservative Jews and sold at Russ and Daughters. “How much do you want?” asked the clerk. “Enough for 12 people.” Noting my squeamishness at the price tag, he assured me sturgeon was a “royal fish,” meaning any sturgeon, whale, dolphin, or porpoise caught near British shores legally belongs to the royal family. I also bought pumpernickel cocktail bread and dill-horseradish cream cheese, for tea sandwiches fit for a queen.

On Orchard Street, I noticed a “clearance sale” sign outside a nameless leather goods store. When I left, I had a Russ and Daughters bag in my hand and an ushanka on my head. Why do things halfway?

Eggs, milk, flour, butter: All happy pancakes are alike. Blintzes are similar to crepes, but are richer, softer, and more permissive of browned air bubbles. A blintz keeps its filling—in this case, a mix of farmer’s cheese, sour cream, and mascarpone—very snug. You wouldn’t be able to fold a crepe so many times without it cracking from the pressure. I served them with a blackberry compote, but also left bottles of raspberry and spearmint jam open.

My roommate baked an apple sharlotka, a fluffy sponge cake that resembles the inside of an apple pie. My friend Heidi brought two hexagonal tins of caviar, salmon and trout, and positioned them in a Tupperware container filled with crushed ice. Later, the caviar leftovers settled in my fridge, I was murkily reminded of a James Salter story in which a wealthy woman is ditched by her dinner guests; the beluga caviar she laid out for them sits tragically untouched.

While I did offer a selection of the teas I already had—English Breakfast, “The Earl of Harlem,” herbal detox tea for clear skin—and heated water in a bright orange electric kettle, the absence of a samovar cooled the “tea party” aspect of my soiree. Instead, I served white Russians, which are not at all Russian. However by the end of the evening, there was no vodka left behind, which is very Russian.