Habitat for Humanity

Manhattan is rife with lumberjacks, Los Angeles is hot for Appalachia, and the latest trend in pornography is cabins. Yes, cabins. But when a woman leaves New York for a log structure of her own, a metamorphosis occurs.

If you’ve ever left your hometown only to return, once or twice, or several times, chances are you’re familiar with the question, “What are you doing back?” As if being in your own town is akin to buying real estate on Mars. It’s a failure to launch. At least, a failure to launch properly. But I prefer to think of those of us who move home as the subjects of a physics experiment that pits the pull of the world against our origins’ gravitational attraction.

Almost exactly a year ago I moved from New York back to my hometown of Charlottesville, Va. It was the day after Thanksgiving; a couple of weeks earlier I’d had a prophylactic mastectomy because of a genetic condition that puts me at high risk for breast and ovarian cancers. I was reeling and sad, looking for life to be quiet and uneventful. I spent the first weeks at my parents’ home. After that, I crashed for a couple months in the basement apartment of my best friend’s house, waking each morning to the sound of her toddler running across the floor above me. I moved out of the basement. Now, for seven months, I’ve been living in a log cabin 20 minutes from town, near a crossroads called Free Union.

If figurines were awarded for completing twentysomething life-experience clichés, I have been angling for the entire set: the search for myself in central European beer halls; the move west to try growing up with the country; graduate school in New York. A log cabin in the woods has the air of the final trinket on the mantle: the Walden moment. Collect them all.

The popular website Cabin Porn caters to people who envision chucking it all for some peace and quiet. It features beautiful photographs of small houses in lonely landscapes. “A former telephone hut converted into a wilderness library and resting cabin in Lemmenjoki, Finland,” one caption says. “Refuge hut in western Iceland, complete with blow-away prevention device,” says another. These are the sorts of uninsulated sheds, rooms piled high with bear rugs in the Canadian Yukon, where a person can hear through the white noise of the world to the little beating heart of it all, if that is indeed what people hear when the white noise is muted.

Saying “no” to a log cabin in the woods, I decided, was tantamount to saying “no” to life itself.

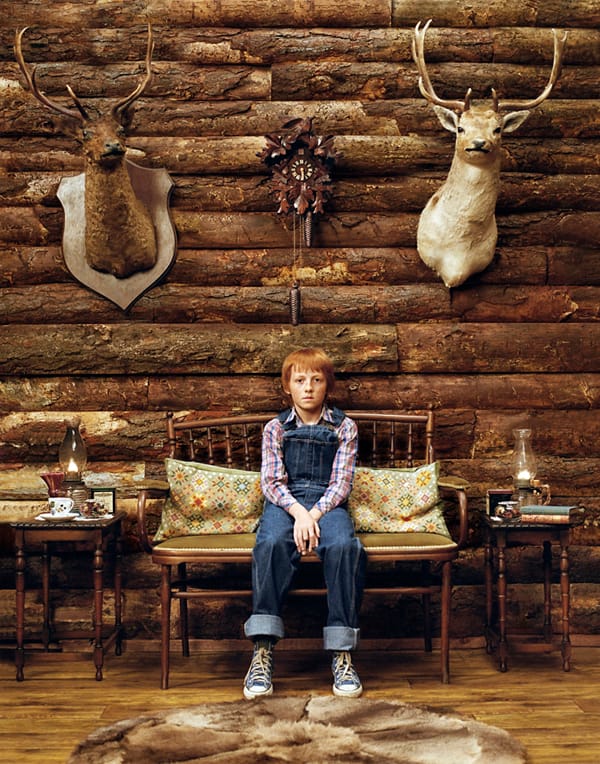

My cabin could be the poster cabin of American cabins. It is situated about a mile up a dirt road that navigates the ridge of a hill flanked by two rivers. The driveway is to the left if you’re heading south, and begins in a field of tall grasses, transitions to woods, then opens up again into a clearing. The cabin sits in this clearing, surrounded on two sides by cow pastures, and on two sides by forest. A hill to the rear leads down to the Mechums River. The house itself is constructed of wooden logs with white chinking. Two stone chimneys flank the structure, and a stone foundation supports it. The roof is cedar shingle. A slab of stone is the step up to the front door. Inside, it is, ostensibly, one room, with a sleeping loft and bathroom. The ceiling follows the pitch of the roof. There is a fireplace, a back door, and five windows. It smells of wood and dirt and stone and the ash of old fires. Nothing creaks. Even when the countryside is loud with the machinery of crickets, the house is silent; it feels as solid as a mountain.

When friends see the place for the first time, they say either, “Oh, it’s really a log cabin,” as if I had been lying or exaggerating, or “Oh, it’s like Little House on the Prairie.” This reference strikes me as an oddly consistent foul ball; I correct them: “Little House in the Big Woods,” I say.

The cabin was built with purpose, but won with chance. My landlord’s father used to play poker with a group of friends from around Virginia. At one of the games, a guy threw the cabin into the pot. My landlord’s father won the hand and the house. He dismantled it, salvaged what he could, and began to rebuild it on the spot where it now stands. Then, he was diagnosed with cancer. He lived for another year and spent almost every day in the cabin, putting the place back together, restoring it, whittling the wooden pegs where I now hang my coats and bath towels. When a tree fell in a storm, he fashioned from its trunk the spiral staircase to the loft where I sleep and the railing that leads me there.

I have no stomach for snakes, bees, or wasps. I foster a longstanding fear that I will die after having contracted hantavirus. My fire-making chops are lacking. I am lazy at best when it comes checking myself for ticks. And yet, after experiencing something like an illness or mastectomy or both, people often find they want to do something that testifies to the tangible, exerted worth of their bodies. This is apparent when pink-shirted runners pass by during a marathon, or when the gym offers a deal for anyone who’s recently had surgery. People want to run a 5K or climb a mountain. They want to surmount something. I’m no different; I tried running for a few weeks only to remember how much I hated it. When an ad for the cabin appeared in my inbox, it offered an alternative. I wasn’t going to build a log cabin, but living in one would let me learn how to face snakes and build fires. I could prove my physical abilities while catering to my search for peace and quiet. A log cabin symbolizes nothing if not equal parts nothing-doing, shit-shooting, porch-sitting, and classic American ideals of self-sufficiency and independence.

650 sq. ft. Authentic Log Cabin, Secluded in Free Union Area with private driveway, Fireplace & thermostat propane stove heat, 1 loft bedroom, 1 bathroom, galley kitchen and washer/dryer, $775/month + utilities, References required.

In New York, I couldn’t conceive of what a real life in a real cabin in a real forest or tundra or open plain might actually look like. That didn’t stop me from daydreaming. Black thumb be damned, I would have a garden and it would grow edible plants, and tending that garden with a sunhat on would be good for my skin and help stabilize my mood. Produce would be pickled. A typical day might involve coffee and Morning Edition, and then setting out for an unmapped walk through the woods. Making small-yet-big observations about the brutal daily routines that dictate the world of insects. I’d return in mid-afternoon, energized, full of deep thoughts, and ready to write them down because that, after all, is the crux of imagined cabin life: the writing that gets done as a result of it. The writing would last hours and come fluently. If, at night, someone happened upon the cabin in a non-creepy way, they might see a light on in a window and think, “Someone is busy in there.”

When I thought about the prospect practically, I couldn’t deny the element of running away from one world just to hide in another that permeates the cabin-life fantasy. Just because a trade is made doesn’t mean any one or many problems have been solved.

I called the landlord. Saying “no” to a log cabin in the woods, I decided, was tantamount to saying “no” to life itself.

I moved here in June. It took some weeks, before the drive to town and back began to feel more like a commute, less like an Appalachian safari among the deer and possum, raccoons and groundhogs, foxes and coyotes. A routine set in. A rhythm developed that revolved around the curves in and out of the driveway, the sound of the tires going from gravel to asphalt.

Now that it’s cold, I spend my extra hours contemplating whether or not to wear my bathrobe to bed over my long johns. How to make the fire more robust. I listen to the radio and look out the window to see if I’ll understand once and for all what my dog does when she doesn’t know I’m watching. When it was warm out, I would sit naked in the grass and read a book. I pulled on the minimum of clothing and walked to a rock that overlooks the river where I sat not reading but just staring down at the way the river curves around the bend between the hills. I don’t know how all these small tasks piled up to fill the time, but they did and that time has not felt wasted.

I now know how to sleep while holding a stinkbug that has crawled into my hand so as not to crush it and make the whole house smell.

But what I have not done was what I hoped I would do most and best: Write. I have written almost nothing here. What I have written has been bad. I almost don’t care. I came looking to make sense of what I had done to my body, what it meant to lose my breasts. In the months since I’ve been living at the cabin I’ve learned that maybe a mastectomy isn’t something to figure out, maybe it’s just something that is. Or maybe, too, it’s neither something to figure out nor passively accept, but a compromise between grasping and letting go.

I have also not learned to garden. But I now know how to sleep while holding a stinkbug that has crawled into my hand so as not to crush it and make the whole house smell. There’s the way cows can share a field with deer. How the domestic live side-by-side with the wild: I know about that now, and about how being alone in a city is a different thing entirely from being alone in the woods. While I will never be an expert, I am better at building fires.

Because I couldn’t resist, a few weeks ago I went out and bought a copy of Little House in the Big Woods to reread for the first time since childhood. I went to the used bookstore in town and purchased a paperback edition for two dollars. It was just as I remembered, though the paper was heavier, the font larger. There are the same classic watercolor-pencil illustrations of Laura and her blond sister Mary making molasses candy and sleeping all together in one bed in the attic and buying sacks of salt and yards of calico at the general store. The plot still glorifies the resourcefulness of the Ingalls family, as Ma keeps the fire going, Pa hunts by day and plays the fiddle by night, and Laura and Mary give their beds hospital corners and wrap corncobs in handkerchiefs to pretend they are dolls. Reading it in the cabin made their lives all the more immediate: When I would look up from the novel and around me, it seemed entirely plausible that the Ingalls had all just stepped out and would be back at any moment.

From its first words, the book stakes its claim as an American fairy tale:

Once upon a time, sixty years ago, a little girl lived in the Big Woods of Wisconsin, in a little gray house made of logs.

The great, dark trees of the Big Woods stood all around the house, and beyond them were other trees and beyond them were more trees. … and the wild animals who had their homes among them.

Some of the most common words in the book appear in these lines: dark, trees, woods, house, wild, home. Over the course of thirteen chapters the warm coziness of the cabin is repeatedly contrasted against the terrors that lurk in the woods beyond the fence line. Terrors like bears and snow drifts that various family members must confront and conquer. The morality lessons about blood and hard work are not subtle.

After the wild animals and bad weather have been shot or survived, the book ends with a quaint scene of the family gathered around the fire at night as Pa plays fiddle and Ma knits, and Laura the child thinks to herself, “This is now.” Laura, the adult children’s book author, then concludes about that child thinking that unchildish thought, “She was glad that the cosy house, and Pa and Ma and the firelight and the music were now. They could not be forgotten… because now is now. It can never be a long time ago.”

I left my cabin this week, not for work or vacation, but for the foreseeable future. I packed up and took a job in Philadelphia. I’m leaving because it’s a job that will let me pay my bills on time, in which I will grow with people from whom I have a great deal to learn. I am looking forward to the experience. I was raised to consider the world a big place, full of adventure. I believe this, which is why I took the cabin, and now, too, why I have left it. But at this point I have also been told too many times and by too many writing instructors that the best stories are often found within single grains of sand. And I agree.

The ideal landscape is one in which there is an open field with a pond, some animals in the foreground, and the woods in the background, the border between field and forest marked by a fence.

It’s the grains of sand I’ll miss most. There’s the ancient pony and his donkey friend that live down the road and who like to be scratched on their haunches and behind their ears. There’s the view of Buck Mountain from between the trees beyond the field where the pony and the donkey graze, and then there are the four curves of my gravel driveway, and the five pines, twelve spruces, eight oaks, and three ash trees I could hit with a stone if I threw it from my porch and had better aim. I am leaving the creak and bang of the screen door. The copperheads for which I kept a rake on hand, its tongs sharp and ready to sink into a reptilian skull. I am leaving the way the morning sun fills the entire house. The spot in the shower where, through the chinking, I could see outside. I am leaving the miscalibration of the oven, the broken back burner of the stove, the spider webs spun in the grasses in the field by the mailbox, and the guttural sounds cows make when they give birth. I am leaving a pile of firewood, chopped and ready for winter. I am leaving the stars at night.

My sister, a landscape architect, tells me studies have been conducted across cultures and the whole world seems to agree on at least one point: The ideal landscape is one in which there is an open field with a pond, some animals in the foreground, and the woods in the background, the border between field and forest marked by a fence. A landscape in which humans have water and food within reach, while the wilderness is kept at bay.

Rereading Little House in the Big Woods as an adult, two facts stand out. First, the name Laura Ingalls took when she married a man named Almanzo: Wilder. That name she took as an adult contains the very word her family tried for a while, and for a while succeeded, to keep locked out of their house when she was a child. Second, it’s just one book—the inaugural book—of a series. Circumstances changed for the family so that they had to pack up for the prairie, and then the banks of Plum Creek, and then the shores of Silver Lake, and so on. I don’t remember exactly why the Ingalls left the woods. But I suppose that the larger point for children reading these chapters and about these chances taken is that as happy as the family was in the cabin, they eventually packed for the plains.