Hammer of the Dads

Joining a band at middle age can feel like a juvenile, shameful pursuit, until you consider all the gear you get to buy. A report on purchasing earplugs and playing live—but why are the crowds so small?—when you're 40.

The hobbies of middle age are often thinly veiled excuses for consumption. The great cliché of a midlife crisis is buying a big-ticket item to revitalize one’s zest for life, something previously kept at bay by cost and practicalities and yet never quite forgotten. It is the indulgence that apparently keeps one fresh. On the surface, a band doesn’t seem like an expensive new hobby—hardly comparable to sports cars or man caves.

At the age of nearly 40, joining a band still feels like an indulgence, a childish, undignified pursuit. I also hadn’t factored in the potential for purchases, and the ways in which my modest disposable income—far, far more than was available to my youthful self—would be lured into upgrades and previously unimaginable indulgences. So the guitar shop, once a glittering cave of the unobtainable, was now a bewildering array of choice. The prickly staff are is now younger, not older, and hence far more intimidating since there is no human way of impressing them. However, the ability to actually buy something trumps lack of experience or skill. I began by purchasing a good set of earplugs.

That was only the start. After the earplugs, I bought a capo. After that, a new foot controller for my effects box. Then I realized I needed a proper guitar amplifier. And I had to get a foot pedal to control the amp. And another foot pedal with more buttons on it to control the bits the first pedal couldn’t. And so on.

After a few months we toyed with the idea of finding a keyboard player, but the far more obvious—and more fun—solution was simply to buy more gear. This time, it was the drummer’s turn to indulge, and we enjoyed a few weeks of stalking various gadgets through the thickets of eBay, before a shiny new drum pad succumbed to his winning bid. A couple of months later he sidled up to rehearsal with a shiny new cymbal. He had bid rather more than he had set out to, of course, and it would be best—we both agreed—if we didn’t discuss its existence with his wife. We also concurred that it wasn’t helpful keeping a mental tally of just how much this stuff was costing us.

We have a combined age of about 122. By the time the Beatles hit 122, they’d been broken up for over two years.

Being old in a band encourages mental arithmetic. We have a combined age of about 122. You have to go back to 1967 for the five core members of the Rolling Stones to add up to such a weighty total. By the time the Beatles hit 122, they’d been broken up for over two years. When Paul McCartney started Wings he was 29, with the entire recorded output of the Beatles behind him. U2, a band of teenagers, finally arrived at 122 in around 1994, some 18 years into the band’s existence.

Rock and roll is for the young. At 18 I was convinced that I had to put out a seven-inch single by the age of 20 or else it would be all over and I would have utterly failed in my modest ambitions. The deadline shifted to 25. Then 30. Within a few years of that milestone, the thought of assembling a band and entering a studio had fallen far down the list of priorities: marriage, houses, children.

Around about this time, I realized with discomfort that I was the strange old man standing at the back of gigs, utterly disconnected from the gaggle of teenagers down the front. When I was their age, I was genuinely perplexed by the presence of “old” people at gigs, considering them lonely or perverse. Or lost.

The earplugs were a prescient buy. After a few months, it became apparent that I have a new type of tinnitus. The shrill whine that rose and fell in intensity in the days after I’d attended a gig had slowly subsided after 20 years of diligent earplug use and mental re-tuning. I only noticed it at night, when even the sounds of the city couldn’t completely eradicate the buzz.

And then I joined a band. Now the incessant whine has been joined by another, lower, companion. Again, it was at night when I first became aware of this new intrusive frequency, low and pulsing, as if distant machinery was slowly grinding its way through the evening shift, or if a large vehicle was standing idling a few streets away. For a while, I thought it might be the appearance of London’s very own urban “hum,” a quasi-mythological 21st century malaise with no explanation or cure. But the hum followed me wherever I went and it didn’t take long to correlate cause and effect. I now bolster the earplugs by shielding the drummer with a large acoustic panel. A Plexiglas box is not yet on the shopping list.

Forty is looming. I hadn’t marked it down as yet another musical deadline, but it’s one that I’ll miss nonetheless. Maybe aim for 41? Happily, the arbitrary definition of “over-the-hill” is an elastic barrier that one pushes ahead of one’s life, helping define the here and now. Forty-five? Now that’s old. I’ll practically have a teenager of my own by that point, someone to be properly and authentically disgusted and embarrassed by what his father gets up to.

The nagging thought that I should be doing something a little more grown up with my precious spare time never goes away. At 40, my own father was on the cusp of giving up what he had been trained to do since his mid-teens—fly helicopters—in favor of desk-based operations and eventual early retirement. Today’s stretched and shifted generations are good at making excuses for the things they enjoy, forgetting just how rigid life and work could be just a few decades before.

I touched Kim Gordon’s leg once. Well, her cowboy boot. Until the call came, this was as close as I’d ever gotten to the stage. I don’t remember much about it—I was only 16—but I still have her autograph on the back of a folded, sweat-stained flyer. I saw her again that evening, when drunken bravado and faulty navigation allowed me to stumble into a dark back room after the gig. As she scrawled her name on the scrap, I said to her, “I touched your leg! It was me! I touched your leg! Do you remember?” The look she gave me was a studious combination of pity and disinterest. But it didn’t matter.

And now we’re up on the stage, carrying with us a heavy burden of expectation, memories, and pop cultural history. We know how our idols started out, and where they went, but this provides only a tiny fraction of their experience. Ambition and ignorance sugarcoat teenage disappointment and help you push on to another level. It’s 23 years since I first thought this was something I really wanted to do, and we are taking a very different approach.

There are no heights to ascend to, no career path to follow, just a workmanlike sense of getting the job done without disgracing ourselves.

A writer, a communications director, and a graphic designer make an unlikely power trio. We can’t even claim an authentic backstory. I know the drummer from the school playground. Our sons are in the same class. He persistently invited me along to hear his band play and I responded with persistent procrastination; the potential for awkward conversations was high. Eventually I gave in, just as their guitarist (a TV producer) departed for a lucrative contract in the Middle East (again, the rock family tree is threadbare). Would I be interested in joining?

The rest, as they probably won’t say, is history. From where we are now, it’s plain that there are no heights to ascend to, no career path to follow, just a workmanlike sense of getting the job done without disgracing ourselves. Admiration is hard to come by, and there’s always the nagging feeling that compliments are just people’s way of being polite. Has a friend ever asked you what you think of their unpublished novel? Exactly. The term “midlife crisis” never carried much meaning in the first few decades of life, but it seems strangely apt now. There’s light-hearted derision from family and friends, the faint hint of social discomfort, the raising of an eyebrow. I’m inadvertently going against the social status quo, a perverse form of rebellion. Just as the teenager revels in their parents’ distaste for their music, evoking any reaction—even if it is just embarrassment—is a form of justification.

As we progress through our modest setlist of self-penned songs, I finally come to understand that there are only two types of band. There are bands that will only ever be seen by family and friends, and friends of friends, maybe even some friends of theirs. And there are those bands that will be seen by people that they don’t personally know—people they have never met and who may never even catch their eye.

It’s easily possible for an entire musical career to pass without even beginning to make the transition from one state to another. At this stage of life, it’s almost an inevitability that any fans—and I am suspicious of the word and the sentiment—will be drawn from the former camp, not the latter.

Playing live for the first time induced a panic like I’d never known. Age did not bring wisdom. Instead, it placed an onerous burden on our performance, with audience expectations that were simultaneously high and low. Did we represent some awesome slice of undiscovered audio archaeology? Or are we just lame beyond belief? The fact that our own tour bus was a biscuit-crumb-filled Mercedes station wagon complete with kids’ booster seats didn’t exactly raise our credibility. The bands we support are young enough to be our children. Is it perhaps worse to be “old” up on stage than to be old and unhip and lurking at the back of the audience? And why are audiences so small?

Bands are like babies: If you have one, it’s tough to be objective and step back and see what others might perceive as their damp, screaming unloveliness.

The nebulous accounting systems of the music industry lies many levels above us, so we’re content to remain ignorant of their workings. But the system for booking gigs, for example, gives a little indication of larger complexities. From what I can see, promoters are the most likely to win. No one has to pay to play, exactly, but we find ourselves making impossible promises as to the number of people who will come to our shows. They demand a minimum of 20. “Easy,” we reply in order to secure the gig, then cast around our limited pool and drop heavy hints. Breach that magic number and the promoter might offer a cut of door receipts.

After five gigs, we have achieved this distinction merely once. Our total combined takings for nearly 10 months of music-making? Fifteen pounds.

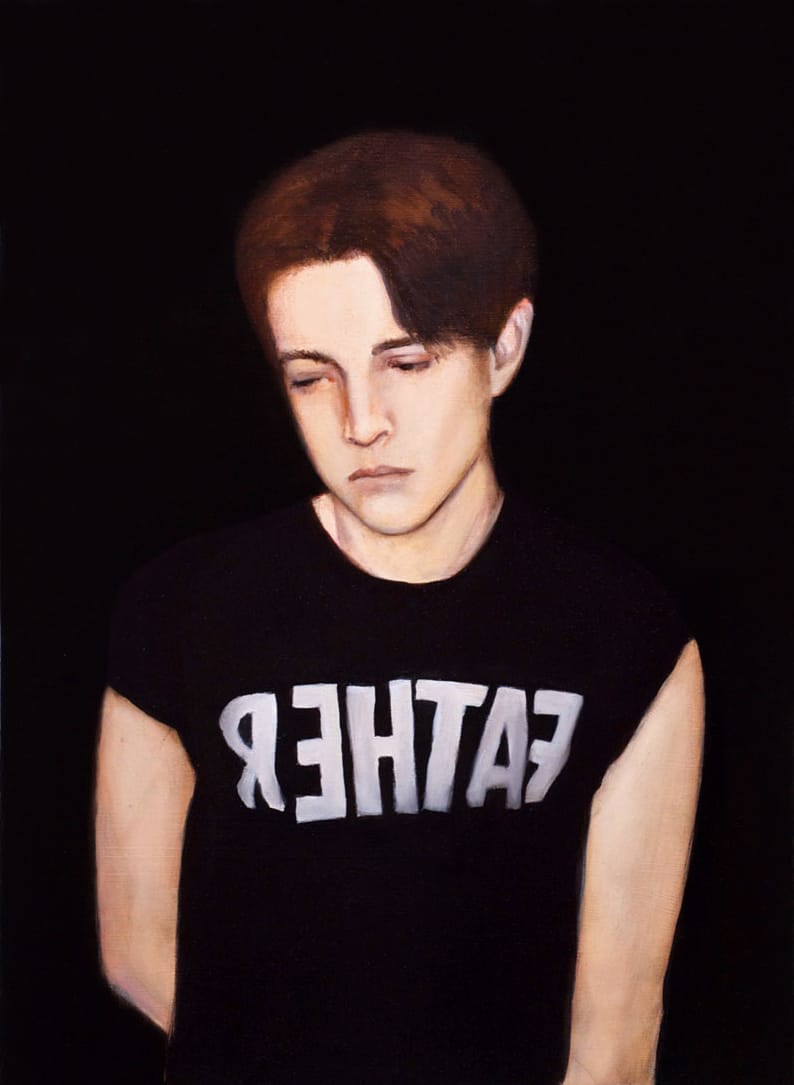

The urban dictionary seems to disagree on the precise definition of the pejorative term “dad rock.” Personally, I prefer the inherent futility of its second explanation: “The term ‘dad rock’ refers to older music listened to by men who try, without success, to introduce this music to their children and other younger people.” But maybe we represent yet another classification. We are dads rocking. Mix that stark reality in with the bleak musical wasteland listed in the urban dictionary (Dire Straits, Tom Petty, Phil Collins, Sting) and it becomes clear that being a fortysomething band member is seen as aging, rather than a youthful, invigorating tonic that knocks off the years. People in bands may have kids, but people with kids rarely start bands.

Bands are like babies: If you have one, it’s tough to be objective and step back and see what others might perceive as their damp, screaming unloveliness. Right now, it’s hard to say exactly which moments I’m supposed to savor. Is it stepping on stage, exchanging awkward smiles with fellow parents from my son’s school from a stage six inches above them? Or is it straining to hear my own guitar through the precisely engineered barrier of rubber and plastic that cossets the last shreds of my hearing from another rehearsal? Or is the post-practice analysis in a quiet pub surrounded by south London art students, all studiously cool and—obviously—entirely disinterested in the secret knowledge of our musicianship that we carry around? Is it telling people, sometimes proudly, often bashfully, that, yes, I’m in a band? Or is about trawling the internet for gadgets and gizmos that will magically make us sound a bit better?

Perhaps it’s none of these things. As I click on “record” to commit the evening’s rehearsal to wav file (yet another essential purchase—a digital pocket recorder), I think I finally get what this is really all about: We’re making our own nostalgia for future consumption, an investment for the eventual, inevitable, retirement. All this will one day end and these fragments of audio will be the last traces of our fleeting genius. Then nostalgia’s butterscotch varnish will take over, lacquering the reality in a shiny, crisp shell that will fossilize this episode for consumption.

We’re now accustomed to the vast accumulation of data that we all trail behind us as we snap, blog, tweet, and post our way through modern life. It lurks on backed-up DVDs, thumb drives, external disks, and up in the cloud, awaiting a leisured reassessment. Like many amateurs, I have a modest rack of self-created audio cassettes, compilations of compositions comped together with mic’d up boomboxes and primitive four-track recorders, tinny drum boxes and cheap microphones. To anyone else but me, this scratchy audio is pure aural trash, irrelevant and unlistenable. Yet I have kept these tapes alive, together with all the mp3 files that were amateurishly outputted from free audio software in the decades that followed. All this data is a repository for a later day rather than an urgent snapshot of the present. Along with my burgeoning collection of ear defenders and plugs, these recordings will accompany me into retirement, memories of a brief but bright attempt to bring the hopes of the past to bear on my experience of the future.