Happy Misgivings

Thanksgiving is an American holiday, but that doesn’t mean it’s not celebrated elsewhere. And each of those celebrations—in Liberia, in Leiden, in the South Pacific—give us fresh reasons to be grateful for our own messed-up version.

In Liberia, Thanksgiving is celebrated on the first Thursday in November. Families gather to eat cayenne-spiced roast chicken, mashed cassavas, and green-bean casserole.

If my grandmother was lucky enough to visit a Liberian Thanksgiving, she’d want a large vodka with an ice cube.

In the Dutch city of Leiden, where the Pilgrims lived for 11 years before their long journey to Plymouth, there is a non-denominational service in the Pieterskerk, a late-Gothic church built between 1390 and 1570. Protestant ministers, a Catholic priest, and a Jewish rabbi participate. The choir and the band of the American School perform. Scouts do a flag ceremony.

If my youngest cousin, John, was in Leiden on Thanksgiving, he’d want to take part in the flag ceremony, sing “God Is Good” to the tune of “Rock Around the Clock,” and eat dinner rolls until he wasn’t hungry for supper. If my grandmother was there with him, she’d have John fetch her a vodka with an ice cube.

Some Floridians believe the first American Thanksgiving happened near St. Augustine, where Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, 500 soldiers, 200 sailors, and 100 civilian families joined with a group of Timucuan Indians for a feast on Saturday, September 8, 1565. Like many later Thanksgivings, it was a potluck: The Timucuans contributed oysters and giant clams. The Spaniards added bread, pork, wine, and garbanzo beans.

My Uncle Tim always brings the stuffing from his house in Hopewell, N.J. After two big vodkas, my grandmother has no problem telling the table that that his contribution tastes like Muesli.

We’re all thankful for a familiar version of that extraordinary bounty; the one that preserves peace and finds harmony despite everything else.

American sailors introduced Thanksgiving to Norfolk Island in the South Pacific in the late 19th century. There, it’s celebrated on the fourth Wednesday in November with decorative corn stalks and sugarcane grasses and a potluck lunch that only occasionally involves turkey.

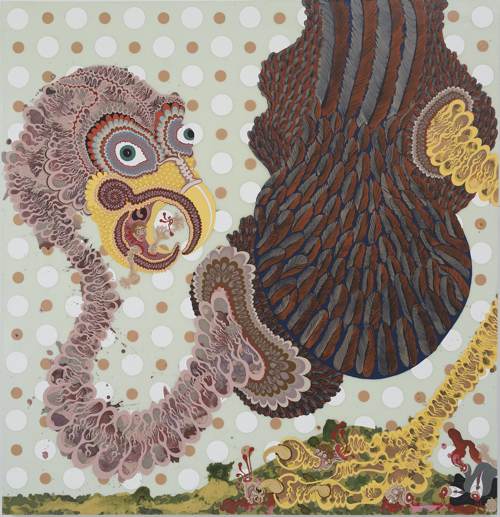

We always have turkey. And my Uncle James—who’s actually my second cousin—always brings the centerpiece. It’s low and long and autumnal, and when my grandmother starts to get really nasty, he quietly pours her glass of vodka into the gourds and native grasses that make up the arrangement’s perimeter. We all act like nothing happened.

Until 1863, most Americans living outside of New England didn’t celebrate Thanksgiving, and in the states that did, there wasn’t much agreement on the date: Governors who wished to participate would pick a day and issue a public statement of thanks.

Our feast starts promptly at 1 p.m., so it can finish before 5 p.m., so my grandmother won’t fall asleep at the table.

In his “Proclamation of Thanksgiving,” Abraham Lincoln acknowledged “the blessing of fruitful fields and healthful skies,” then quickly moved on to bounties of “so extraordinary a nature that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible.” “In the midst of a civil war of unequalled magnitude and severity,” he wrote, “peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict.”

For me, tomorrow, and maybe in Liberia a few weeks ago, and in Leiden, and Canada and throughout history, too, I’d guess we’re all thankful for a familiar version of that extraordinary bounty; the one that preserves peace and finds harmony despite everything else. So cheers to you, Grandma. And happy Thanksgiving.