Shockingly, terrifyingly, I discover that I have responsibilities over the four days of my cousin’s wedding: Because Manisha doesn’t have a brother, I am to serve as a surrogate. My first task is to go along with my uncle Jawahar to attend the thread ceremony for Manisha’s fiancé, Sumit. As far as I can tell, this 16-hour marathon involves wearing a lot of orange, getting smooched by elderly women, and alternately sitting cross-legged and traipsing around a fire, all while a lethargic guy in a dhoti chants and flings flower petals at pictures of deities. Sporadically, Coca-Cola is served.

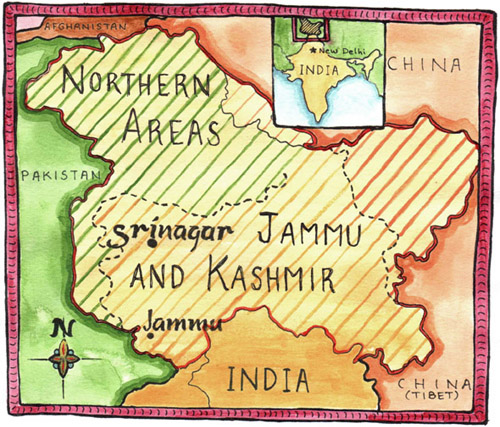

The ceremony is held in a temple that is a replica of one in Srinagar, rebuilt in a predominantly Kashmiri neighborhood of Jammu. The temple is painted in varying pastel shades, resembles a fancy, tiered cake, and pokes up conspicuously amidst the square cement houses. My uncle and I remove our shoes and, through a gauntlet of bowing strangers, make our way toward a raised dais at the back of the temple. On stage, Sumit is being kissed by an old woman shaped like a question mark. We sit. Someone brings us pakoras. The Coca-Cola flows.

When it is our turn to greet Sumit, I hang back. I feel suddenly like I do at Catholic ceremonies when everyone but me goes up to take communion: an outsider, unworthy of participation. Now, amidst all these pious Hindus, I am painfully self-aware of how much I love a good steak—the thicker and juicier and bloodier, the better.

From my seat I watch the priest tie a red thread around my uncle’s wrist and swipe his forehead with a finger dipped in orange paint. Three young Sikhs step up to take video, and Sumit and Jawahar pose together, as though for a snapshot. The camera rolls. After the requisite amount of footage is committed to tape, the camera is lowered, and son- and father-in-law to be, as though reincarnated or thawed, shake hands and part.

The following morning a different priest comes to our family’s house to perform another puja, which will last all day. Everyone clusters around a fire on the upstairs landing and the chanting begins. This time, my job is to help throw symbolic offerings onto the fire: flowers, spices, bits of wood, whatever. The problem is that my instructions come in Sharda and then in Kashmiri—regardless, it takes me a while to figure out when I’m being prompted to make another offering. But once I get the hang of it, I start to showboat; I develop this stylized wrist flourish, like a magician. When the priest hands me a wad of a few hundred rupees, I enthusiastically chuck these also into the flames. A cry rises up as the money crinkles and burns. Apparently, I’ve just given Ganesh or Vishnu or whoever the customary payment due to the bride’s brother for his services. While the priest shakes his head in disbelief, a tut-tutting aunt relieves me of any further duties.

I decide to track down my cousin Asha, who lives in England and whom I notice has also bailed on the puja. I find her on the rooftop veranda, gazing out over Jammu. I ask her about these ceremonies: Our family isn’t otherwise religious, but for whatever reason has adopted an almost alarming level of piety for the wedding. Asha tells me, “Without these traditions, who are we? You have to have some sort of identity.” Still, she makes no move to go back downstairs.

The next day involves a meal with both families, and then a live band will play traditional Kashmiri folk songs from dusk until dawn. This is my dad’s favorite part of any wedding, and since he couldn’t come—my stepmother is battling cancer back in Canada—he has made me promise to stay awake for the entire night. I have told him I will try.

Asha tells me, “Without these traditions, who are we? You have to have some sort of identity.” Once supper is over, the tables are cleared away and mattresses, thick comforters, and pillows are laid out on the floor of the hall. Everyone reclines as the band starts the first song of what will amount to a 10-hour set. The amps have been cranked, so the instruments—sarod, tabla, santoor, harmonium, voice—crackle with distortion; the volume of the music is a weird contrast to the relaxed attitudes of the reclining listeners, many of whom look ready to nap.

A pot of henna makes its rounds: You are meant to mark yourself and then hand it off to the next person. I draw a Wu-Tang “W” on my palm and pass the pot to my sister, Cara, who shakes her head at me. “Not cool,” she says, applying a sensible streak to her own hand. “Not cool at all.” Then my cousin Pinky, a successful, “A-grade” recording artist, decides to get up and do a number with the band. Pinky releases albums under her birth-name, Loveleena, and the Hindi hits she belts out have little in common with the ancient Sufi traditions and mysticism from which much Kashmiri music is derived. The musicians do their best to follow along as she sings a song they’ve likely never played—and possibly never heard—before. The applause when she finally steps down seems to be as much out of relief as celebration.

When the band resumes, it is with an intensity that goes beyond the blaring P.A. and buzz of constant feedback. The Kashmiri songs that my dad loves so much share Qawwali’s call-and-response and accelerating percussion; the singers’ voices urge one another on—at first gentle, then deliberate, then hysterical. Dancing involves grabbing someone by the wrists and spinning them around in what seems an attempt to create a centrifugal vortex. Cara and I are convinced one fiendish-looking member of Sumit’s family is trying to dislocate our shoulders.

At around 2 a.m., I start to fade. So do Cara and her boyfriend. We lie down. Between songs, I doze off for a bit but am roused awake once the music starts to kick up again. An aunt tells me someone can take us back to the house. “Everyone will probably come home soon,” she tells me—this woman of 60, still up, still bright-eyed. We decide: OK. The next morning I get up at seven and discover a kitchen full of relatives. “How late did you stay last night?” I ask them, pouring myself some tea. “We just got in,” says one. Another reminds me that my dad would have stayed all night, too.

The matrimonial ceremony is the next day at a hall next door to the Kashmir Gun Emporium. Inside are two thrones placed on a stage before a few hundred folding chairs and, on the lawn, buffet tables are lined up for the meal. It is hot; people waiting for the bride and groom to arrive fan themselves with their invitations. When Manisha and Sumit (she looking resplendent, piled with gold and wrapped in silk; he with a princely air in his Nehru jacket and jeweled, pointed shoes) show up and make their way to the stage, there is surprisingly little fanfare. Before they even take their seats, word spreads that food is being served outside, and the guests begin to sneak out the door. By the time the priest loops the wedding garlands, lei-style, over the young couple’s heads, there are fewer than a dozen of the two hundred-or-so invitees left in the hall. Everyone else is visible through the louver doors, plates in hand, slopping up various vegetarian dishes with chapatis.

After the ceremony, I am told I have more responsibilities. “You have to push the car,” an uncle tells me. Push the car? Manisha is being carried out of the hall on the shoulders of a man I’ve never seen before. A few people shower her with petals. Everyone else continues to talk and eat on the lawn. “Push the car,” the uncle says. “You must do it now.” So I follow Manisha to the waiting automobile. She and Sumit are ushered inside and I position myself behind the rear fender. “Here?” I ask the uncle. “Push the car!” he commands me. People begin flinging handfuls of money over the vehicle’s hood; out of nowhere, street urchins appear to scoop up what they can. “Push the car!” someone else yells. So I push it, and the car begins to move.

“Now get in!” someone—Sumit’s mother, I think—screams.

“Get in?”

“Go!”

The rear door swings open and I run up and hop into the moving automobile, the car I have presumably ushered into motion. I look back: the few people gathered in the street cheer while the beggars assess their earnings. Sumit helps close the door. Where are we going?

The car, it turns out, is taking me to Sumit’s parents’ house; apparently it is now my role, as Manisha’s “brother,” to hand her over to her new family. At the in-laws’, I can’t help but wonder if either bride or groom is thinking ahead to the act of consummation that presumably awaits them later that evening. And, more so, I consider that, as the one stewarding Manisha into marriage, how I am oddly—and uncomfortably—complicit in that act.

There are maybe 30 people congregated in Sumit’s family’s home. The women sit on the floor in a circle, banging pots and pans and jangling keys, while the men perch clapping on stools around the periphery. Manisha and I are stationed (regally, I have to admit) on a pile of cushions at the front of the room. Beneath her make-up and jewels, my cousin is reserved, reticent. Her recently appointed husband hovers nearby, talking with his friends, occasionally turning to ask if she’d like something to drink.

All of a sudden, everyone is singing.

Around the circle they go, someone starting up a tune and then everyone joining in. These begin with Kashmiri folk songs and move quickly to Bollywood. After half an hour or so, there is a pause, some Kashmiri discussion, and then everyone turns to me.

“Now,” says Sumit’s mother, “it is your turn to sing a song.”

“A song? I don’t know any Indian songs.”

All that comes to mind is Wu-Tang Clan. I can’t possibly sing Wu-Tang Clan at my cousin’s wedding, before I hand her over to be deflowered. “Then sing your favorite song. And stand up, stand up!”

I move into the middle of the circle in my suit. A roomful of faces looks up at me with expectation in their eyes. Manisha is trying not to laugh.

My favorite song—OK, easy enough.

But, standing there, the room hushed, all that comes to mind is Wu-Tang Clan. I can’t possibly sing Wu-Tang Clan at my cousin’s wedding, before I hand her over to be deflowered. What is wrong with me? Why can I not think of anything except “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing Ta Fuck Wit”?

Finally, after more than a few moments of total silence, I come up with the answer: “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star,” which I belt out with an abandon I didn’t know I was capable of. It seems to take forever, but my final “How I wonder what you are!” (joined raucously by one tone-deaf, elderly gentleman in the back) is followed by lackluster applause, and, thankfully, I am permitted to sit back down.

I arrive back at my uncle Jawahar’s house to a parlor-full of family members sharing a six-pack of beer. The wedding has been necessarily dry—“Nothing worse than a drunk Indian,” Asha has told me—and now, with things finally over, it’s time to get back into the booze.

I sit down and someone hands me a half-full beer. I tip back a mouthful, pass it along, and then another relative gives me the phone, which I hadn’t realized was in use. “It’s your dad,” I’m told, “calling from Canada.” His voice is faint; there’s an echo over the crackling line. “How was the wedding?” he asks. “Long,” I tell him. He laughs. I ask him how my stepmom is doing; he says, “Oh, you know,” and trails off.

The line goes still. I wonder for a moment if we’ve been disconnected, but through the silence, I hear a sharp intake of breath—as though my dad is fighting back tears. But I’m not sure. No one has ever seemed so far away.