How to Drink in Qatar

The World Cup and its drunken fans are about to crash head-first into a repressive, restrictive society, where alcohol is illegal mostly everywhere.

The Persian Gulf is the sort of place where you have to keep your vices hidden, so let’s just call him Abdulrahman. His gold watch clatters as he pounds the table for another drink. Across the room, the bartender looks up and nods in Abdulrahman’s direction and says something in Tagalog to the waiter. The employees know Abdulrahman. They know he never orders at the bar. They know he likes sweet cocktails and sambuca shots. They know the table he likes by the window, where he usually sits with his friends, other Qataris in wrinkled thaubs stained with beer dribble and cigarette ash. The waiter smiles deferentially, and Abdulrahman slurs his order and dismisses him with a wave.

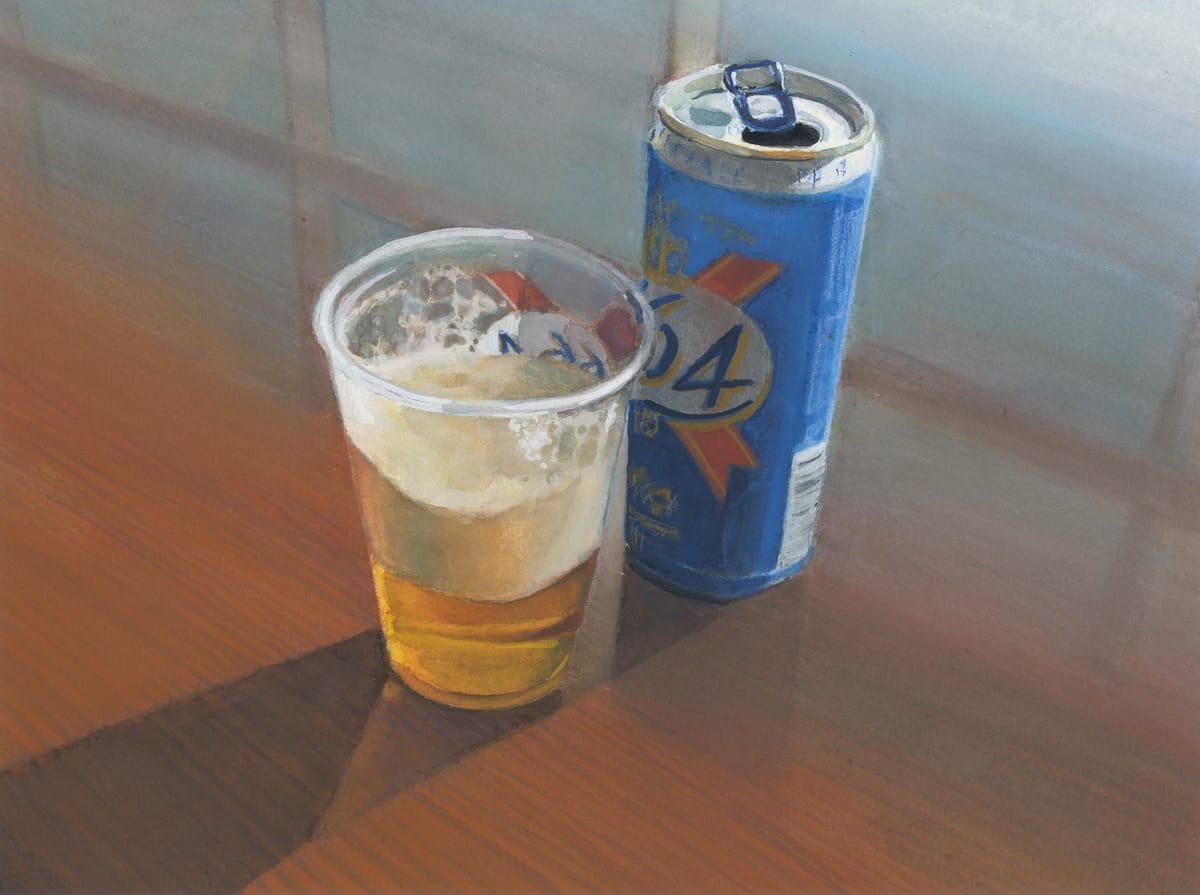

He adjusts the ghutra and akal on his head and fixes the gold pen in his breast pocket and looks up in our direction. We’re sitting around a table in the back corner, drinking individual pitchers of Fosters through bendy straws. The staff always laughs when we order this, and we’re pretty sure they all make fun of us back in the kitchen, but as a general rule we’re bored, and personal pitcher nights have become kind of a thing for us. We know we’re ridiculous, but we don’t really know any other way to exist in Doha. We’re a bunch of self-conscious expats from all over and, rather than adopt aloofness, we try to embrace being ridiculous. It helps to level the playing field. It feels honest.

Recognition registers on Abdulrahman’s face when he spots us. He likes our general group—not because we’re particularly smart or interesting, but because we’re affable enough, we can drink our own weight in booze, and we don’t judge a Qatari man who does, too—that and it helps to have a couple Brits around. In the Gulf, the British still get deferential treatment. The accent and a suit will take you far there.

He crosses the room and his sandals make the characteristic flop you get used to hearing everywhere, as they’re more less a part of the national uniform. He pats himself down for a lighter. One of my friends, a squinty Englishman with a Lilliputian stature and a Brobdingnagian lexicon, is particularly drunk, and he almost knocks his chair over to intercept Abdulrahman and offer a light. The Englishman gets a kick, as I guess we all do, out of being somewhat accepted here by a local, and Abdulrahman gets a kick out of the Englishman’s little witticisms. Abdulrahman rarely actually remembers me personally, even if he claims to recall my good character when I stand him a shot. Not that he needs the generosity. Odds are he has lots more money than any of us. Yet, rather than throw on a shirt and a blazer and head to more fashionable Doha destinations, like La Cigale’s Sky Bar or the W’s Crystal or the Four Seasons Beach Party or anywhere else the local glitterati hung out, he chooses, night after night, to come here, to the Old Manor.

The Old Manor—or the Manor, as regulars call it—sits on the top floor of the Mercure Hotel, an older building in the heart of downtown Doha. While most of the new development for the 2022 World Cup and the continuing population boom in and around the Qatari capital city have pushed nightlife to the shiny high rises and resorts in the Western expat areas of town, the Mercure makes its stand downtown, serving beer, steak sandwiches, and alcoholic asylum in what is generally a dry neighborhood.

Like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, Qatar derives much of its law from Sharia, Islamic law as interpreted by scholars and judges. Unlike in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, as well as Sharjah in the UAE, however, finding a drink is not a hardship. There is one store called the Qatar Distribution Center, where you can buy haram goods, namely alcohol and pork. The QDC is, perhaps not coincidentally, on the outskirts of the city, halfway out to the Ar-Rayyan desert, and not a far drive from Our Lady of the Rosary, the only Christian church in town. This vice district, as it’s sometimes jokingly called, is a concession to the expats living within Qatar’s borders. But that community of expats, if you can call it that, comprises more than 90 percent of the labor force and roughly 86 percent of the country’s population; you’re almost as likely to hear English or Urdu or one of India’s many languages on the streets as you are to hear Arabic.

Just several dozen bars serve the entire country, all in or around Doha, where the majority of the populace is concentrated as well. With the exception of a few private clubs, all legal bars are on hotel property, neatly separating the act of imbibing from the rest of public life. Many of these establishments are typical of hotel restaurants and lounges: sterile, functional, and not really built for the thirsty crowds that often pack them. In addition to the paucity of watering holes, every one of them is expensive, even the cheap ones. A 12-ounce lager is going to cost you at least 30 riyals ($8.24), but more likely, it will run anywhere from QR35 ($9.61) to QR55 ($15.11). Cocktails are often $20 or more. To justify the prices and give the hotels a level of cachet, a lot of bars aspire to some level of club- or lounge-style ritz. Sometimes the effort leads to comic dissonance: sports bars with ambient club lighting, wood-and-brass pubs where the lights go down and the DJ beats go up, piss-elegant cocktail lounges where people forgo espresso martinis to slug down warm 22s of Kingfisher and shoot back Cuervo shots like it’s last call at Señor Frog’s.

World Cup visitors are going to want to drink. And when they inevitably get drunk, how is Qatar going to control them?

One of the obvious benefits of a place like the Old Manor is that it’s cheaper than most bars in the city. But its main draw, which is also a rarity in Doha, is its low visibility. Doha is a city where things are increasingly new and shiny and bright, and people move there for only two reasons: to make names for themselves and make some money. Many bars feed into this perception of conspicuous success with bouncers, velvet ropes, special elevators, and garish red carpet events where people can pose and mug for cameras. None of these trappings of exclusivity are actually inaccessible to anyone who can afford the drinks inside and remember to wear appropriate footwear, but the measures give patrons a way to be seen in a place where they believe it’s worth it to be seen. Basically, your average desk jockey gets to feel like a celebrity. The Old Manor, on the other hand, exists in part because it’s hard to find and it doesn’t have publicized events—or unpublicized ones, for that matter. It’s why it attracts some Qataris, who generally have sober reputations to uphold. But this doesn’t mean it’s exclusive; it’ll take anyone who can slap the necessary riyals on the bar top. In any town in America or Europe, this kind of no-frills drinking is pretty much the standard. In Qatar, this is a rarity, especially in places frequented by degree-holding young professionals.

The Manor is loosely styled after an English pub. Not the picturesque kind you’ll find in the tonier areas of London or the quaint alehouses in the country; it’s more like a banausic, suburban Wetherspoon—functional above all else. Still, there are obvious differences. Instead of hand-pulled casks and an array of cold lager and cider taps, the only taps are Heineken and Foster’s, which, along with Stella, are standard in pretty much every bar from Salalah to Manama. The room is a lived-in hodgepodge of faded glory: nicked wood tables, worn leather armchairs, grainy TVs mounted with gilt frames and showing stilted Arab dance programming, bookshelves filled with brittle mass-market paperbacks in French, drilling engineers rubbing elbows with Bahrainis and Saudis and Kuwaitis—a menagerie of creased faces under a cumulonimbus of cigarette smoke.

The thing you first notice, though, is how people are dressed; the Old Manor is the only proper bar in the country where I’ve found that Gulf men are allowed to drink while wearing the thaub (ankle-length shirt/robe), the ghutra (headscarf), and the akal (coiled cord that holds down the ghutra). Usually, traditional Khaleeji, or Gulf, clothing is verboten in bars, and even in hotel restaurants where alcohol is allowed, seeing men drink while dressed in the thaub is an anomaly; generally, Khaleejis dress in Western garb if they’re going to drink in public. Yet, for reasons no one seems to know, the Manor is an exception: Qatari men wear thaubs and sandals as they slouch in armchairs and hold pints in one hand while they play with prayer beads in the other. Every time I’ve asked a staff member why this is so, the answer is always the same: “It’s been this way since I started working here.”

In the mid-’80s, the population of Qatar was fewer than 400,000 people. Now it stands at over 2 million, and more than half the residents—and some 70 percent of the men—live in labor camps. While some of the newer camps are supposed to have appropriate housing for families, most house single men. As a result, the country’s ratio of men to women skews to almost 3.5 to 1. Life in labor housing is crowded, and while conditions are slowly improving, it was not too long ago that squeezing a dozen men into a room and having them sleep in shifts was standard practice. Though there are recreational facilities in the newer housing, there still isn’t much in the way of entertainment in these zones. On the weekends, many workers gather in the open public spaces of Doha where they aren’t chased off for loitering—typically in the older neighborhoods that haven’t yet been converted to mixed-used facilities and tourist attractions. Spaces like this are becoming harder to come by as Qatar continues to rebrand itself as an international tourism destination.

Not surprisingly, these single males aren’t welcome where families gather in the evenings and on the weekends, like shopping malls. Fridays are the Saturdays of the Islamic weekend, and on Fridays, many of the malls have Family Day, when single men aren’t allowed to be there. This is supposedly to ensure the safety and comfort of women and children, but the rule isn’t equally enforced; white and Arab men come and go, unstopped. I strolled freely as a single man through the malls on Fridays, and no one I know has ever seen a white or Arab man denied entry on a Friday. (Non-white Westerners can be a different story, though usually an American or British passport sorts it out.) While many pastimes—alcoholic and otherwise—exist to keep a minority of privileged foreigners entertained enough to stick around, the same considerations don’t apply to workers who require fewer luxuries in order to decide to pack up and head to Doha.

There are a few little-known spots for the labor class to go drink, and the cheapest one is also in the Mercure. In a smoky, windowless room in the basement, a Filipino cover band plays hits for a clientele composed almost entirely of South Asian and Sub-Saharan African men. The drinks are a relative bargain at QR25 ($6.87) and, more importantly, the crowd can drink, dance, and shower the band with single-riyal notes without worrying about what wealthy expats and locals will think, or whether or not they have to act deferentially around their social superiors. This is in keeping with the neighborhood around the Mercure, called Musheireb. It is one of the only places with some kind of working-class street presence when the heat dissipates a little. At night, you can walk the crowded streets and jangled alleys lit by the bright signage of shops, surrounded by polylinguistic white noise and road rage that bubble up in between the sand-colored buildings that were put up before mixed-use skyscraper development became a local hobby.

But the neighborhood is not exempt from revitalization efforts. The old outdoor market, or souq, was renovated a decade ago to look like a traditional market made of adobe and wood. While you can still buy cheap cookware and textiles and tchotchke and jewelry and pets and kebabs and coffee and sweets and flatbread, and you can still smoke shisha and play backgammon in little spots down back alleys, you can now also stay in expensive boutique hotels and get spa treatments and splurge on upscale Levantine, Maghrebi, and Persian meals served on rococo platters while a man plays the oud by a fountain. Then, after you enjoy a stroll and some ice cream or fruit smoothies, you can peruse an antique store that displays both Nazi paraphernalia and elephant tusks. The souq is dry and thus family-friendly, a conscious aspect of much of the country’s gentrification. The phrase “family-friendly,” while meaning “alcohol-free,” also becomes an easy excuse to keep out the supposed riff-raff. It’s doubtful the laborers will be welcome in the new mixed-use development spanning several city blocks across the street from the Mercure.

The city radiates outward from the Corniche, a seven-kilometer-long crescent-shaped esplanade on the Persian Gulf that was finished in the early '80s. At the south end, marked by the I.M. Pei-designed Museum of Islamic Art, is the old city; it is one of the few areas of town with pedestrian traffic, and it’s also one of the few areas where people of varying economic statuses mingle. At the north end of the Corniche is an area called Al Dafna, which translates to “landfill,” because the neighborhood is just that—a peninsula of reclaimed dirt and sand. However, people tend to call the neighborhood the Diplomatic Area, both for its concentration of embassies and its popularity with expats who can afford the expensive flats there. It has the largest collection of high rises in the city and, with its many hotels within walking distance of the residential towers, it’s the center of nightlife in Doha. This is a fairly new phenomenon for the city, as the Diplomatic Area as it exists now is barely more than a decade old. (An old tower in Dafna would be one whose age reaches the double digits.)

Describing Doha’s growth as rapid doesn’t really do it justice. The native population isn’t growing at the rate at which expats are arriving, making Qataris an increasingly smaller minority in their own country. With this comes a lot of anxiety about not only maintaining the traditional culture, but determining what the traditional culture is, as well as how that tradition can negotiate with the plurality of foreign influences and behaviors.

For when you can’t stomach the idea of another night at the W Hotel.

The Korean: Technically it isn’t a real bar and it isn’t actually in any place you’d call Doha and it doesn’t actually have a real name, but this unmarked villa serves cheap San Miguel, cold soju, tasty Korean barbecue, karaoke, and guaranteed bad decisions. One man’s opinion: It’s the most fun place in Qatar. (Location: Ask around and maybe someone will be nice enough to take you there on the sly.)

The Belgian Café: Yeah, it’s a chain, but the crowded, smoky bar is the only place you’re going to find a Maredsous bottle or two kinds of Leffe on tap. (Location: InterContinental Hotel)

Rugby Club: As a non-member, you need someone to sign you in, but once you’re there, you can drink from a wide array of taps and bottles and pretend you’re in Aberdeen or somewhere similarly grotty. (Location: Rugby Club)

The Rose & Thistle: If you don’t mind struggling through patrons’ Geordie accents and having to look at the simultaneously new and dated décor, you can’t beat the prices for when a pint of plain is your only man. (Location: Horizon Manor Hotel)

The Library: There are no books in this library, but a couple of the bartenders actually know what they’re doing with the bitters and shakers; plus, you get to look around you at the wood paneling and feel like a tony shit. Ask if Vincent is working, and then see if he can get someone to make you a First Edition. (Location: Four Seasons Hotel)

For instance, there is the lingering World Cup question of how the country will handle, among other things, drinking. There will be alcohol. That much is a given. But how and where will it be distributed? Drinking is illegal at stadiums—and at the museums, theaters, concert halls, malls, markets, and anywhere else visitors are going to gather outside of the hotels, where bars already have just enough capacity for their existing patrons. But World Cup visitors are going to want to drink.

And when they inevitably get drunk, how is Qatar going to control them? While the Gulf does love soccer, the rowdiest the locals tend to get is creating traffic jams. Qatar has never experienced roving bands of football hooligans. And, unlike larger countries, with cities spread out across them, you can’t spread everyone out in Qatar; it’s too small and there are no cities other than Doha to speak of. One solution that has been floated is to put people on luxury boats out in the water. The other plans are equally far-fetched.

It’s no surprise to the world that Qatar, like its Gulf neighbors on the Arabian Peninsula, has repressive and heavily restrictive laws regarding decency and morality. While women can drive and don’t have to cover their heads, showing some knee can get you kicked out of places. Kissing in public can get you jail time, deportation, or both, if the wrong person sees you. Similarly, fights, especially ones involving local Qataris, don’t end well for people, and even verbal tussles can end in tragedy if the other party decides to claim you insulted the Prophet. Perceived criticism of the government can be repackaged by the authorities as incitement to rebellion and earn you a lifetime sentence.

Even in a place like Dubai, where the economy is highly dependent on the kind of tourism that involves expensive drinks and sex work, kissing in public can still land you in a cell. The same is true in Doha, where sex workers are visible in a lot of the hotels. There are drugs to be found, but the penalty for smuggling can be death. Drunk driving can get you deported immediately, but drunk drivers flood the roads at night. Homosexuality is a huge no-no, but Grindr use is common and certain bars operate nearly openly as gay clubs. Even in Saudi Arabia, perhaps the strictest and most repressive of the countries making up the Gulf Cooperation Council, the city of Jeddah’s down-low gay scene is a destination.

The thing is, Doha, and the Gulf in general, is a lot like the patrons at the Old Manor. It’s not uncommon, after a night at the Mercure, for the men to stumble down to the parking garage and change into a clean thaub they’ve left hanging in the backseat of the SUV so they can arrive home without anyone seeing stains or smelling cigarette smoke. Then they start their cars and swerve off into the night. It’s about maintaining that façade of moral rectitude. And that kind of strict public morality, whether you’re in Indiana or Iran, is almost invariably about power and control.

Even without the World Cup to worry about, Westerners have a habit of making their own fun, to the chagrin of local management. With a dearth of things to do in the heat, social life, which takes its cues from the Brits, becomes a long succession of drinks in a limited number of venues, so finding a new spot becomes a big deal. As a result, there’s a phenomenon of patrons socially retrofitting bars, transforming stuffy or swanky establishments into local watering holes, because it’s all you have. The Four Seasons learned this the hard way. In order to turn a greater profit, the management at the Library, an oak-paneled bar off the marble lobby, instituted Martini Monday, a special in which you could get three-martini flight for QR70 ($19.23). It was so cheap it’d have been crazy not to order one. My extended circle of morons descended regularly on the place, and soon others followed. Eventually, the staff, accustomed to leisurely evenings of business dinners and dates the rest of the week, came to dread Mondays. Mercifully, both for the harried staff and the patrons tossing back multiple flights, management canceled the special, since Al Jazeera journalists vomiting on the floors and lawyers doing impromptu Jay-Z recitations wasn’t the brand image the Four Seasons was going for.

And that’s the thing about planning and control as the country tries to manage its growth—it only works up to a point. People tend to find a way to get shitfaced in an undignified manner (or Manor) if that’s what they’re after. That’s how it goes with human beings and their desire to blow off steam. It’s a bit inspiring, when you think about it.

Because Westerners in Qatar all tend to live in the same areas of town and, as a whole, the Westerners don’t actually make up that much of the population—Americans and Britons, the largest groups, together make up only about 1.5 percent of the total—it often feels for expats like everyone knows everyone. As a result, with a disposable income and a safe distance from the responsibilities of life back home, Western adults have a habit of reverting to a kind of adolescence in Doha. North of the Diplomatic Area is a neighborhood compound called West Bay Lagoon. It consists of large, walled villas and streets that snake around an inlet off the Gulf. It’s adjacent to the Pearl, Qatar’s answer to Dubai’s Palm Island. West Bay Lagoon is popular with Westerners, because while it’s built for families, the four-plus-bedroom homes are conducive to big parties. The living rooms and bathrooms and terraces end up dirtied with various party residues and mud and dregs spilled from cans of Efes and bottles of Magners—and in the morning a maid will clean it up. It’s a fitting symbol for a lot of what life can be like for Westerners. It’s a big reason many are in no hurry to leave.

The native population isn’t growing at the rate at which expats are arriving, making Qataris an increasingly smaller minority in their own country.

Yet almost everyone leaves eventually. Bureaucratic hassles, professional roadblocks, homesickness, geographic fear of missing out, and boredom erode the wall of comfort people build up around themselves in Doha. Financially, it’s almost always stupid to leave, but there is a powerful sense that the world is moving on without you and that Doha isn’t part of the real world. For some people, it takes less than a year for this sense to grow strong enough; for others it’s the better part of a decade. For me it was three years.

When Westerners leave Doha, they tend to do one of three things: The first option is to hit one of the big, fuck-off brunches. The fancy hotels that serve alcohol almost all have an opulent Friday brunch from noon to four. They cost about $100 but you get all the sparkling wine and signature cocktails you can pour down your throat. Plus, the food, normally laid out in a lavish and eclectic buffet of Arab and foreign cuisines, is usually pretty good, which is important, because you need something to soak up the gurgling mass of Buck’s Fizz pressing against your pyloric canal. The second is to gather at one of the nicer hotel bars to experience the novelty of feigned wealth one last time, before the material realities of New York or London grind down the sense of self you’ve built. The third option is to do the first and then the second.

But the night before I hopped a one-way flight back to New York, I dragged my friends to the Old Manor for one last go-round. In its grubby way, it is one of the most honest establishments in the city; it’s certainly the only bar in town that isn’t a pale approximation of something else. In its stripping of local social barriers, it creates an odd sort of egalitarianism, or as close to it as you’re going to find in Qatar.

Around midnight, we settle up our tabs so we can make it back to the Diplomatic Area before last call. As when most people leave, it feels like the end of something more than just one’s stay. Living in Doha, you get used to saying goodbye as people come and go and friendships undergo a constant process of revision. You get used to bittersweet moments.

I take a last look out the window at all the development going up around the Mercure. At night it looks like its own small city of towers and light. We wave goodbye to the bartender and make our way down to the ground. Outside the air is soupy and the street is humming with pedestrians and the taxi drivers smoke outside their parked cars and try to yell over each other for our attention. We pile into a van and, as is customary, we argue with the driver about which way to go.