Where the Streets Have One Name

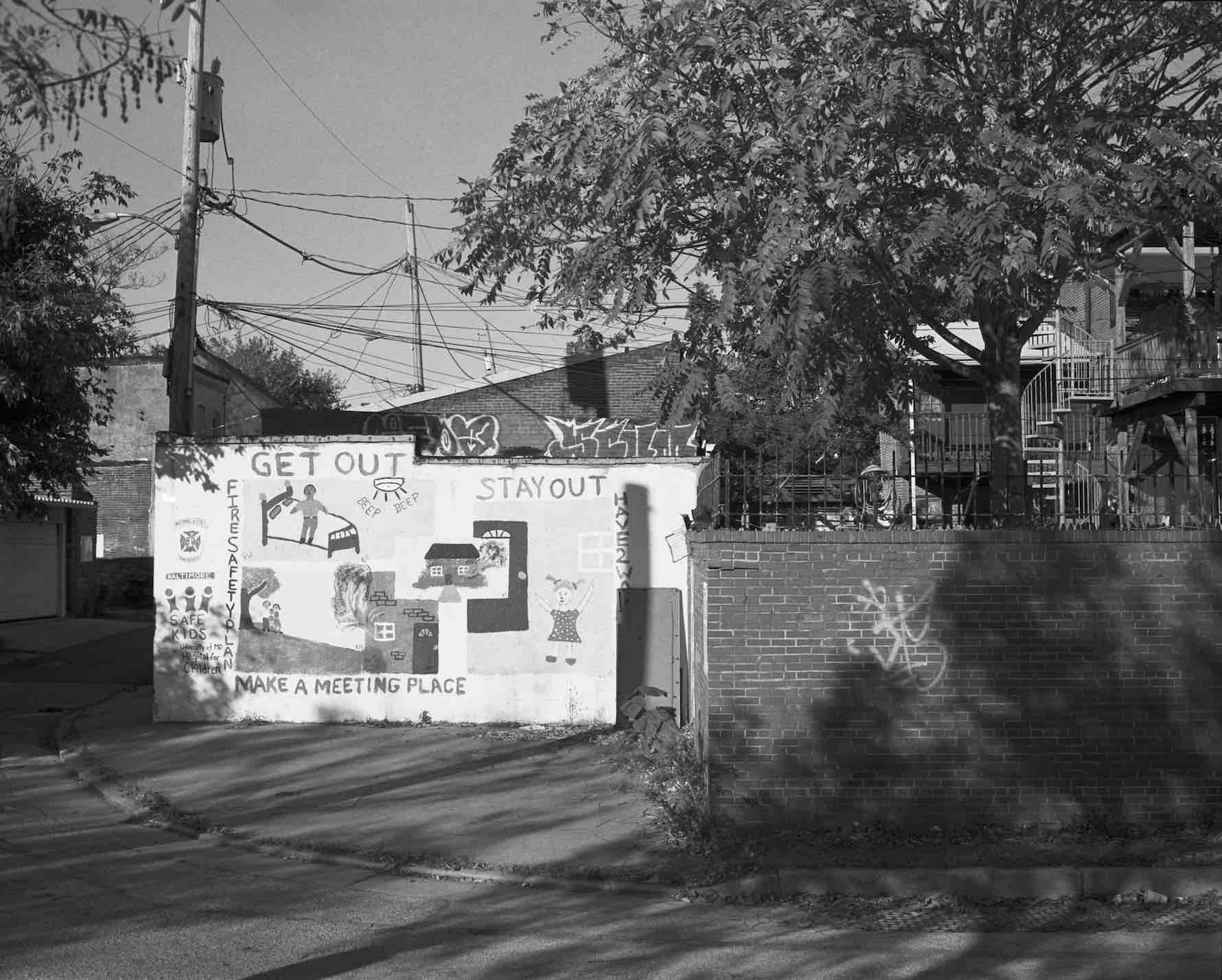

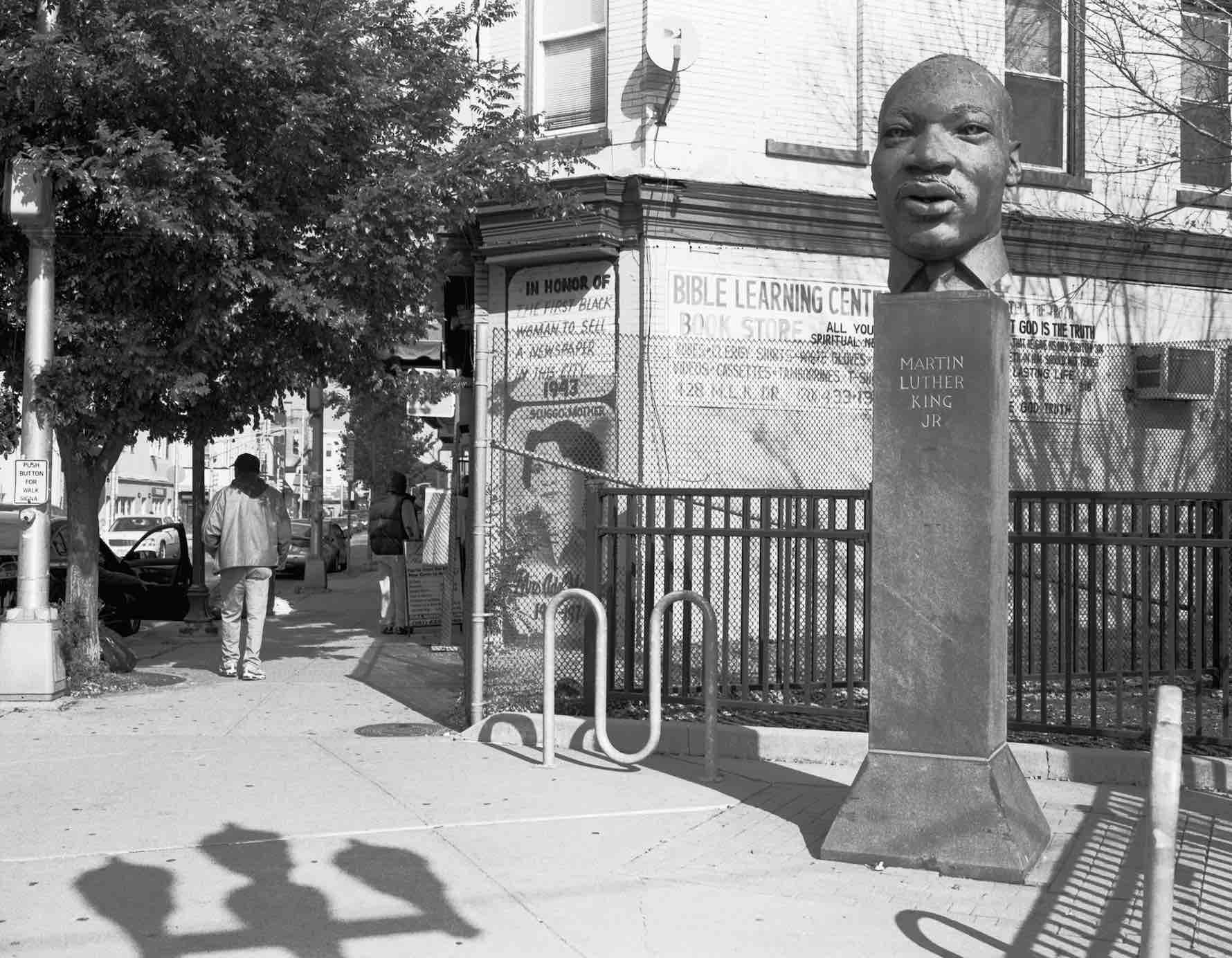

What is the best way to honor a man like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.? Photographs from a cross-country trip to document streets named after the American icon.

Interview by Karolle Rabarison

The Morning News: It was back in 2009 that you set out on a Robert Frank-esque road trip to photograph streets named in honor of Dr. King. How might these images be different if you revisited the streets today?

Susan Berger: I expect the streets that I found in the neighborhoods to be more Hispanic, less African American. I saw that beginning to happen in 2009 and 2010. In Los Angeles, for example, Martin Luther King Dr. runs through a neighborhood that was a Jewish neighborhood, became an African-American neighborhood, and is now becoming an Hispanic neighborhood. Continue reading ↓

“Martin Luther King Dr” will be on view this year at the Diane Klidd Gallery in Tiffin, Ohio (opening Jan. 18), Santa Monica’s DNJ Gallery (opening Feb. 27), and the University of Arizona Museum of Art (opening July 12). All images used with permission. All rights reserved, copyright © the artist.

Interview continued

TMN: Was the pattern you noticed that the streets tended to be in minority neighborhoods?

SB: There were some exceptions. For example, in Philadelphia the street runs through the city’s central park where everyone jogs and rides their bikes. In Beaumont, Texas, it’s a country road. I often found in the ethnic neighborhoods that there was a Hispanic influence mixing in with the African-American community—a taco food truck in Austin; a Mexican restaurant, Mexican grocery, and Mexican hair salon in Los Angeles.

TMN: You photographed street corners, building signs—did you have a chance to interact with residents in these neighborhoods?

SB: Yes, I did, although not as much as I imagined I would before I began the project. We’ve become such an automobile-dependent society that often there are no people on the streets. Everyone I met was very friendly and welcoming. Of course, they were curious about this white woman with a big camera photographing on their streets. When I told them what I was doing, they were very excited. Some of them suggested things for me to photograph. Others just wanted to talk about the neighborhood. There was a great deal of pride about the neighborhood. And some just wanted to chat about themselves.

TMN: What’s a favorite story you heard along the way?

SB: In Jersey City, I met a woman who was a teacher in one of the local schools. Without any prompting from me, she started telling me about her students. She told me that she was trying to teach her female students how to act with boys. She was particularly concerned with them demanding that the boys treat them with respect. She was telling them to “make sure they know your name first, make sure they pick you up at home and take you back home.”

We’ve become such an automobile-dependent society that often there are no people on the streets.

I think there was some frustration that they weren’t learning this at home. But I was impressed that she had the kind of relationship with her students where she could discuss this subject with them. By the way, that teacher was Hispanic although the community is strongly African American.

TMN: What did you learn about yourself or photography as a medium while you were on the road?

SB: I really found myself doing a lot of soul-searching while working on this project. As I walked up and down Martin Luther King Dr., I was choosing what to photograph and what not to. I had to start thinking about what my choices said about me. The photographer has the ability to tell exactly the story he or she wants to tell and can sway public opinion by only documenting those scenes that tell that story—like how newspapers and politicians only report the facts that support their opinions.

TMN: In light of the Black Lives Matter movement and nonstop coverage of racial tensions in the US the past year, some would argue much of Dr. King’s dream of equality and freedom has yet to be fulfilled. As these photographs continue to circulate amidst this struggle for equality, have viewers come to consider the project activism?

SB: I haven’t heard anyone refer to the project that way, but it opens up a lot of possibilities for discussion. Most definitely one of them is the question of how much Dr. King’s dream has been realized. At least legally the dream has been realized—there are specific laws regarding voting, hiring, housing, etc. But there’s no question that racism still exists in this country. Changing people’s hearts and minds has become a much more difficult task.

TMN: You’ve been known to be partial to black and white. Which photographers do you admire for their work in color?

SB: It’s true my medium is silver-gelatin. And if you look at the work hanging on my walls, it’s mostly black and white. But there are so many photographers I admire that work in color. William Christenberry, Edward Burtynsky, Alex and Rebecca Webb, Elger Esser, Aline Smithson. I can go on and on. All I have to do is go down the list of by Facebook friends.