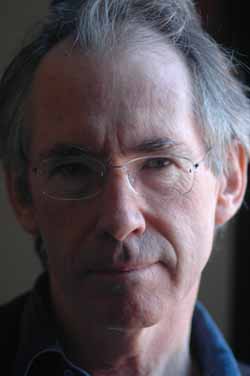

Ian McEwan

It can take six weeks to write six minutes of fiction, and that's not so bad. A conversation with the author of Saturday about taking the time to do your thing, the changing face of literary culture, and how everybody really can write a novel.

Ian McEwan, as the son of a British sergeant major of Scots descent, had a typical, well-traveled, army childhood. A self-described “very mediocre pupil” until he began to be excited by English literature, McEwan started his writing career penning short stories after following up university with a master’s course in creative writing at East Anglia. The first one he submitted was accepted by the New American Review, and the proceeds paid for his trip to Afghanistan in 1971. Upon his return to England, McEwan taught English to non-native speakers and proceeded to write two well-regarded story collections, First Love, Last Rites (which won the Somerset Maugham Award) and In Between the Sheets. McEwan has written nine novels including The Cement Garden, The Comfort of Strangers, The Child in Time, The Innocent, Black Dogs, Enduring Love, Amsterdam, Atonement, and, most recently, Saturday. He has won a Whitbread Award and a Booker Prize.

Saturday describes a 24-hour slice of the life of 48-year-old British neurosurgeon Henry Perowne after he awakens uneasily early one Saturday morning in February 2003 to see a burning airplane in the night sky over London. As the well-to-do doctor goes through his comfortable and civilized life choosing cheeses and vintages, he ruminates.

Perowne held for a while to the idea that it was all an aberration, that the world would surely calm down and soon be otherwise, that solutions were possible, that reason, being a powerful tool, was irresistible, the only way out; or that like any other crisis, this one would fade soon, and make way for the next, going the way of the Falklands and Bosnia, Biafra and Chernobyl. But lately, this is looking optimistic. Against his own inclination, he’s adapting, the way patients eventually do to their sudden loss of sight or use of their limbs. No going back. The nineties are looking like an innocent decade, and who would have thought that at the time? Now we breathe a different air.

The events and interior monologue of Henry’s day are encompassed in a taut and rich narrative that weave the story of the burning airplane, a massive anti-war march, and a minor car accident and might lead one, as it has pushed some reviewers, to conclude that McEwan has written a political novel. Interestingly, McEwan, as is clear in what follows, eschews the extra duties and activities that we have come to expect from novelists. However, he was moved to comment after the recent events in London:

It is unlikely that London will claim to have been transformed in an instant, to have lost its innocence in the course of a morning. It is hard to knock a huge city like this off its course. It has survived many attacks in the past. But once we have counted up our dead, and the numbness turns to anger and grief, we will see that our lives here will be difficult. We have been savagely woken from a pleasant dream. The city will not recover Wednesday’s confidence and joy in a very long time. Who will want to travel on the tube, once it has been cleared? How will we sit at our ease in a restaurant, cinema or theatre? And we will face again that deal we must constantly make and remake with the state—how much power must we grant Leviathan, how much freedom will we be asked to trade for our security?

This is my second conversation with Ian McEwan and, as I expected, despite some time constraints, full and original.

All photos copyright © Robert Birnbaum

Robert Birnbaum: I don’t celebrate this holiday.

Ian McEwan: Is it a holiday?

RB: April Fools’ Day. I’m sure there are cards and department store sales and the banks close.

IMcE: It’s my son’s birthday. He’s kicking around Brazil at the moment.

RB: Beautiful.

IMcE: Yeah, lucky boy. He’s 19. I just tried ringing him.

RB: Is he one of the boys that Saturday is dedicated to?

IMcE: Yes. He is also the model for Theo in the novel. He’s a very personable sort of gentle—

RB: Does that make the novel autobiographical?

IMcE: It has elements, large elements.

RB: Would you have liked to have been a neurosurgeon?

IMcE: No. When Henry Perowne says, “There must be more to life than saving lives,” I’m with him on that.

RB: [laughs] Would you have liked to have been a musician?

IMcE: Oh, yeah. It would have been fun to have been a really good blues musician.

RB: A white one. I don’t know that it would have been fun to be a black one.

IMcE: Yeah and then I would have to be someone else. But yeah, there are various elements—

RB: I am amused by the phrase, “the fullness of time,” mainly because I can’t figure out what it means.

IMcE: Hmm.

RB: It seems like a brainy kind of throwaway line. In the two cases in which I can remember a novel taking place in a small [compacted] period of time—one day. Graham Swift’s novel comes to mind, The Light of Day—

IMcE: Oh yeah. That was a day—I had forgotten that.

RB: What I am getting at is that I have a better sense of what that phrase means when I read a story like yours because it’s just 24 hours, but—

IMcE: Assuming that it takes seven or eight hours to read a medium-length novel, you are getting a sort of mapping, a ratio of one to four or five of real time, real reading time against fictional time, which is an interesting beginning of an approximation. So you could argue that that’s another form of realism, if you like, or an approach to it.

RB: Like those Warhol movies—

IMcE:—filming someone asleep. And the paint drying.

RB: I also thought about whether those people who hold fiction writers in high regard, hold them in high regard because they are able to focus their attention on a longer frame of time than most people, if not all people are able?

IMcE: You mean they have a special gift as readers?

RB: No, the writer creates this slice of time that includes the past and the future and renders it coherent. I take it that when people think of the past present and future it’s this [William] Jamesian “buzzing, blooming confusion.” That’s for those who hold writers in high regard—I’m sure some people do.

IMcE: Some people do. It’s amazing. It carries on. Yeah. There is a vast critical library of works, especially in the last 30 years, on fictional time—which I have never been at all interested in. A lot of theorizing going on about it. Uh—and what I have noted is—because I work fairly slowly—that I sometimes have the impression, because it takes so long to get a passage down, a scene, that it stretches on interminably. Simply because it’s taken me six weeks to get it down. And I am always amazed that it actually occupies eight minutes of reading time. I am often asked, do I think of movies when I am writing, or do I think of how a novel might be made into a film? I never do. The one thing I do think—I’m taking all this time, hours, weeks, years, to get these 100,000 words down. Then I think it does correspond more or less to my experience of making a movie. One hundred and eight minutes is usually two or three years’ work.

RB: And thousands of feet of film.

IMcE: Just for that seamless couple of hours—takes an immense amount of illusion generating and so on. But yet it’s tricky, time in novels. You can freeze the frame and explore just how things stand. I remember doing that in the beginning of Enduring Love. That is a great freedom. And you can move into paragraphs of summary, which just tells you how the next 10 years fell out for a particular character. And there is everything in between.

RB: The idea of reduced attention spans is oft noted—is it part of the idea of the narrator/writer’s skill that they can actually focus on a story line through various stops and starts and twists and turns?

IMcE: Possibly. But it requires readerly work, too. And, as you say, if the conventional wisdom is that attention spans are diminishing, then it becomes a mystery why even cheap, popular, mass-market paperbacks are still selling by the millions. I have never read The DaVinci Code, but clearly 25 million people have, and to do so they have to focus their attention for seven or eight hours, and they might distribute that over a week or two. So that requires quite an act of memory. Maybe the conventional wisdom is wrong. Maybe attention spans are biological not cultural. Maybe it’s out of our hands, and perhaps we try to scare ourselves with one more bad story.

RB: Do you even concern yourself with the debates about the rise and fall of literary culture? Any declinist tendencies?

IMcE: No I don’t. I often talk to my friend Martin Amis about this. He really feels we have fallen from grace.

RB: [laughs]

IMcE: I often think, “What was this golden age to which you hark back to? The ‘50s?” Literary culture was always a minority culture. Every small town you go to you will find some person who is just obsessed by books. They are everywhere, those people, and they pop up in the most unexpected places. Peoples whose lives are in books. They often have a very unhealthy look.

RB: [laughs]

IMcE: I meet these guys and they are usually guys. They have read far more than I have or ever will, these particular kinds of poets and dreamers who really have a mad hunger for reading.

RB: That would be a hopeful sign.

IMcE: I think so. But generally, those guys apart, the novel is sustained by women. And like most of the differences between men and women we find what we get a big chunk in the middle of the bell curve, of women who read constantly and steadily. And among men a far lower number reading but at the far end of the spectrum just a few utterly crazed enthusiasts.

RB: Henry Perowne, the neurosurgeon, is being educated in literature by his poet daughter, Daisy, who looks at him as woefully uneducated. As Saturday unfolds, he is reading Darwin’s Origin of the Species.

IMcE: He’s reading a biography of Darwin. And he has meant to read the Origin of the Species, but he hasn’t quite gotten around to it yet. And he is also reading an unnamed Conrad novel. Conrad himself is very interested in Darwin. Daisy clearly has some thesis—

RB: After finishing the book, I wondered if you intended to make Henry ordinary?

IMcE: It’s hard for a neurosurgeon to be ordinary, really.

RB: [laughs]

IMcE: I don’t think of him as ordinary at all. Obviously he is not socio-economically ordinary.

Growing up in the ‘50s, people didn’t talk to children. You managed children.

RB: You’re right. That’s the wrong characterization. I find something lacking, deficient in him. Self-satisfied?

IMcE: No, I don’t think there is self-satisfaction. I don’t think he is complacent. Some readers have found him so. He is very troubled by the world. And even when he is passing a street sweeper, he immediately speculates about another age when you conveniently believed that everyone held their station in life and that was ordained by God. And how convenient that must once have been. He even thinks of it as a form of anosognosia, which is a psychiatric term for someone suffering from a condition but not recognizing their condition. So no, I think he’s mentally curious and alert. I obviously don’t share his view of literature. At least, I am just prodding away at a notion, actually maybe a complacent notion in literary culture that if you haven’t got literature you are not a really fully sentient moral being.

RB: He does have music.

IMcE: He adores music. He is not a Philistine. Some people have described him as a Philistine because they think that literary culture is the only culture. Many people I know love literature and know nothing of darts or sculpture. And there are many forms in which we express ourselves. And there is a view—and I used to believe in it in my late teens and early 20s—if you weren’t familiar with the canon and if you didn’t live by literature, you weren’t fully human. You weren’t all there. But we all know full well that most people don’t read novels at all and they are perfectly capable of rich sentient lives in which they make moral decisions. So we must be careful of a kind of arrogance about literary culture. That it’s the only way or only form.

RB: Cultural chauvinism.

IMcE: It is a form, or can be. So Henry has his Goldberg Variations, and he admires a Cezanne and admires Coltrane and Bill Evans. Also he reads his daughter’s poetry and he has a response. His view of Dover Beach, for example, is that its musicality is at odds with its pessimism. Well, that’s a sustainable view.

RB: You are quite right, you can’t be ordinary and be a neurosurgeon. Maybe I’m jealous of his good life. Two wonderful kids, loves his wife and excited about his work, likes where he lives and has the opportunity to trouble himself about the world as he chooses.

IMcE: Let’s put it this way: I am not writing an allegory here. I am not making Henry stand for something. But, nevertheless, just a little or maybe a lot below the surface in his confrontation with Baxter is an echo of the confrontation of the rich, satisfied, contented West with a demented strand of a major world religion. And you might think that Henry is more contented than you are, but from the point of view of someone in a slum on the edge of Peshawar or in a northwest frontier province, you are Henry Perowne. You are rich, contented, healthy, and have time for literature and many other things. So in that sense, possibly not an ordinary man, a version of an Everyman with a capital E, he is very unusual in many respects. He finds it erotic to be faithful to his wife all his life. That’s fairly unusual. But I have laid fair various pleasures on him. But for most people—set aside the unemployed and the very sick who can’t get treatment—the vast majority of people teeming through American cities as well as British cities are unprecedentally rich, historically, and unprecedentally contented and have time for pleasure. So in that encounter with Baxter, I am not really saying this is the first world meeting the third world or anything like that. It is a separate matter. But still we are, on the whole, amazingly well off.

RB: Which presents the problem of making social criticism or analysis. What is it for me, a middle class [struggling] artist, who at my worst is doing exponentially better than Nicaraguan campesinos? What is it for someone like me to talk about social justice?

IMcE: Exactly

RB: I wonder if it rings true—as sincere as I believe I am?

IMcE: This is not a novel promoting social justice. It’s a novel that attempts to hold a mirror up to a troubled time. And at the same time unambiguously celebrate the very things we do hold dear. One of them—it’s not simply a matter of “nice red wine”—one of them is rationality. Henry lives by a certain kind of compassionate and rational code of life. Maybe that’s a luxury, too. To live without religion.

RB: His more noble aspect—even in his encounter with Baxter where he flips to diagnosing his assailant, even at the point where it is also a gambit to extricate himself. But in the end when he tries to do something about Baxter’s condition, one could have easily expected him to go in another direction.

IMcE: There is nothing to be done for Baxter’s condition—

RB: The immediate concern about his cerebral hematoma.

IMcE: Oh yeah—near the end of the novel, yeah sure. There were possibilities for revenge, of course. In fact, he forgives him. That’s true. But yes, even Henry’s knowledge is a kind of luxury. The vast amount of knowledge [he has] and he does worry—he’s a man of conscience and he does worry that he has misused his knowledge to escape a beating up on the street. But yes, his rationality and his knowledge are products of an education, which is also a product of a stable society and wealth.

RB: Did you suggest he might have violated a medical canon by the way he dealt with Baxter about his condition?

IMcE: I don’t think there is any medical code broken there. But he does feel—

RB:—guilt for what he does.

IMcE: That he has humiliated this guy. I mean with good cause—he was about to be thrashed within an inch of his life. He takes a gamble on the fact that the other two will not know that Baxter has Huntington’s disease. So yes, it plagues him, somewhat. But what could he have done? And that’s [the issue].

RB: I am trying to recall the last novel I read in which a family is so happy amongst its members. Even the cranky old grandfather poet, who ends up with a display of nobility. Usually someone is a screwup.

IMcE: Well, Daisy is pregnant. And his mother is dying and Grammaticus [the grandfather] is an alcoholic and they just seem fairly standard—

RB: Yes, but it seems not to be troubling enough.

IMcE: That’s not trouble enough, I know. Well, there is trouble elsewhere. His wife almost gets her throat cut and so on. But if I look around me, my friends, yes there are some families with everyone divorcing, there are families with kids with schizophrenia, problems and so on. But there are loads of families where people get on quite well with their grownup children. In fact, I think this generation of kids is far nicer than we were, to their parents, on the whole. My kids were happy to sit around the table and talk and they’d bring their friends. One of the great bridges, which we never had with our parents, is the music. They don’t have a radically—fortunately, my kids don’t like drum and bass—if that was their music than there would be nothing to talk about. Their music is all built on the same rock and roll base of ‘50s and ‘60s, that our music was built on. So we have a bridge.

RB: Are you a better parent than your parents were to you?

IMcE: [pauses] Growing up in the ‘50s, people didn’t talk to children. You managed children. You managed them lovingly—but fathers especially didn’t hang out with their children. You did all the business and management. I am saying the culture has shifted. Feminism can take some credit for drawing men into the business.

RB: My sense of the American family is that many people became parents after WWII who were not prepared for it in the context of rapidly changing culture—that is the thing obtained in their upbringing they weren’t going to apply in the post-war explosion of modernity and this is the generation they raised—

IMcE:—could have gone either way. We could have been even worse parents. I was reading [Richard Yates’s] Revolutionary Road. It’s not only that the parents, adults didn’t talk to children—men and women were in such different planets, too. And that’s broken down enormously. The ways in which people talk to each other. Things have loosened up and children benefit from the way parents not only talk to them but witnessing parents talking to each other.

RB: Might we say something like there is more talking in the culture—we are going through a societal talking cure?

IMcE: Every time I hear another cultural naysayer saying we are all screwed up—

RB: [laughs]

IMcE:—dim and fucked up, one way or another, I say, imagine sending them back to spend a couple of weeks in 1954 in social life and having to put up with guys smoking pipes and being really grimly certain of their authority and women rushing around emptying ashtrays.

RB: I watched a few minutes of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit last evening. It was hilarious. And horrifying. And the recent film Far From Heaven is a laboratory of quaint ‘50s values. Dennis Quaid comes to grips with his homosexuality. His wife falls in love with a wonderful black man.

IMcE: Of course, this is the ‘90s looking at the ‘50s, But yes, everything was done in—I liked it a lot actually. The colors were curious and other worldly.

RB: Cinemacolor or some such?

IMcE: Or Technicolor or one of those revived processes. Yes that was interesting.

RB: How do you now answer the question, “What do you do?” And with what kind of specificity? I would say I was a literary dialogist, as puzzling as that might be. You might say you are a writer—

IMcE: But that’s not very helpful. I would say what I do is [long pause] investigate human nature within a form which also provides a degree of entertainment as well. Or absorption as well. Entertainment in its broadest sense. But to write a novel is to set yourself on a journey of investigation of our condition, where we stand at this particular time in history. Or whatever particular time you want to set the novel.

RB: Does that mean when you completed Saturday, finished Atonement, that you knew things, had a grasp of things that you hadn’t had before?

IMcE: Yeah.

RB: So every fiction is an education.

IMcE: More than an education. Every time I write a novel and I think I am getting it right, I have arrived at a degree of mental freedom that I didn’t have before.

RB: When didn’t you get it right?

IMcE: The Comfort of Strangers. But yes, Henry James talks about that sense of freedom that comes from knowing you have found the correct language for the novel you want to write. And if I answer the question, “Why do you write? Do you write because you have a message? Or what is the role of the writer in the society?”—all those old chestnut questions, it is the pursuit of freedom, pursuit of mental freedom that I would center the answer around.

RB: Has the landscape of literary culture changed that much?

IMcE: In my lifetime?

RB: Yes.

IMcE: Colossally. I started publishing in the mid ‘70s and the literary culture and publishing culture were really unchanged for scores of years. In the ‘70s it was still much as it had been in the ‘30s. My first book came out in ‘75. It was still a fairly gentlemanly, stuffy clubby world. Rather obscure. It was of very little interest to journalists—literary journalists. Novelists received scant advances. It was vulgar to talk of sales. Success meant one good review in the Times Literary Supplement—would do it. Money was not really an issue at all. In the kind of loudness of rock and roll and pop and cinema culture, there was something rather old fashioned about wanting to publish with a main stream firm like Jonathan Cape or Houghton Mifflin or Simon and Schuster. It still has the last remains of a rather tweedy kind of clubable atmosphere. Novelists were not in gossip diarists’ pages, and their divorces were not causes—

RB: Nor their dental work—

IMcE: No certainly not their dental work. And you would not—on the other hand, just to balance this picture—unless you were standing in the Charing Cross Road in Central London, you could walk for miles without finding a bookshop. There were very few bookshops. Where you could buy serious books. There were sprinkled around, but the Waterstones, Borders, Barnes & Noble’s simply did not exist. Although paperbacks were freely available, books were not cheap nor were they as easily to be bought. It changed in the ‘80s when there were a series of buyouts and mergers and small firms got absorbed into larger corporations and started to look at their business methods and accountancy moved up the scale. And in Britain the Booker Prize started to be televised. That was a huge change. And Tim Waterstone opened, within a decade, more than a hundred branches of these giant bookstores and the atmosphere changed enormously. And also the writing changed. Our generation came along. Probably a little more [pauses] formally ambitious. More diverse. That rather stifling little England quality of British literary fiction in the ‘60s and ‘70s got swept away by new arrivals like Timothy Mo and Salman Rushdie and [Kazuo] Ishiguro—new voices bringing in remnants of the old empire. Different Englishes, as it were, came in. Our generation traveled more than our parents [did], despite the world wars. So we were much more at home in America and really the second half of the 20th century really was—

RB:—the American century.

You have to be able to slip away from public attention. The way to do that is not to write the little “my favorite armchair,” “my best holiday,” or front TV programs.

IMcE: The American century for fiction and we were much more excited and fascinated by that than the Kingsley Amis generation.

RB: Were Americans becoming more interested in British literature?

IMcE: It was slow. Not straight away. I remember Philip Roth asked me if I would stand in for some teaching he was meant to be doing—for some reason he couldn’t do it in Philadelphia. And so I said that I would teach a seminar on five British novels published that year.

RB: [laughs]

IMcE: Yeah. I might have been suggesting we study—

RB: Urdu?

IMcE: Yeah, or poison darts of a remote tribe. Anyway, interesting what those novels were. Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, Martin Amis’s Money, Salman Rushdie’s Shame and Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot—and one other that I can’t remember. But all of those writers would now have high recognition.

RB: Basically, part of the contemporary cannon. Did people know Angela Carter here?

IMcE: Oh yeah, she is a quite an icon, especially in the women’s studies world. But you know how many people came to my seminar? Five. Because no one had heard of those writers and they weren’t interested. Actually, they had heard of Rushdie because of Midnight’s Children. The other thing I noted is they said, “You can’t give these kids a book to read a week. They won’t get through it.” So I had to photocopy—make 30-page extracts of each novel. And that seemed very sad.

RB: Can I extrapolate from what you have said that there has been an explosion of literature in pop culture?

IMcE: Not quite that.

RB: At least that it makes more noise.

IMcE: What I mean is that more noise is made about it—rather than it’s making more noise. Suddenly writers were getting Hollywood-size advances because these corporations, having absorbed these firms, wanted names on their lists. And they were prepared to pay despite the rise of accountants and talk of sales; they started paying unreal advances for novels that would never turn out. Never going to profit. And it became somewhat more—an object of interest to people who never read novels.

RB: Would you accept that it seems that culture seems to be able to only handle a few books at a time?

IMcE: Asking me whether it’s true or a truism?

RB: Is it true?

IMcE: [thoughtful pause] No, I don’t think so. I open the book pages of the Nation and—

RB: That immediately puts you in limited company.

IMcE: I had a long review there. [laughs]

RB: I’m not talking about the little magazines. Book review pages, which reflect current pop cultural preoccupations, don’t go much past a handful of books. If you asked someone—the man on the street to name a new book, they would name Saturday and Jon Foer’s book [Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close]. They got an immense amount of reviews.

IMcE: Exactly. That’s why you need to make a real distinction between the perception of someone walking by on the street and the health of the literary culture. I don’t want to become just a sort of cheerleader for it, for how things stand now, but in the ‘70s people were regularly commissioning articles, panels, or conferences around the subject, “Is the Novel Dead? Can it survive television and the electronic age and diminishing attention spans and all the usual things?” Now the view is—it’s rather like what the sonnet was for a gentleman in the late 16th century. Everyone can write a novel. It’s part of your—a mark of your education. Footballers and film stars and singers—

RB:—and doctors.

IMcE: Everybody writes novels. Now it’s just a badge of your adulthood. The problem is going to be the Indians and the chiefs problem. Finding enough readers to spread around.

RB: Like poetry. More people write it than read it.

IMcE: Yeah, I’m afraid that might be true. And the other problem especially for American poetry is no commanding figure. There isn’t a Robert Lowell or a [John] Berryman.

RB: Those types get medication [laughs] these days. It cuts in to their “commanding” personae. How has all this affected you? Are you successful?

IMcE: You mean commercially?

RB: No.

IMcE: Successful? Yes, I am considered to be and they take away this impression. But what happened is that every three or four years I finish a novel and I go around as I am now, I feel this light and heat and I have learned that’s all part of the profession. But you have to have a tidal view of this. You have to be able to slip away from public attention. The way to do that is not to write the little “my favorite armchair,” “my best holiday,” or front TV programs or be constantly—

RB: Or write short stories—

IMcE:—for our Christmas issue—not to do those. I get maybe 50 requests a week, may be a hundred for this or that.

RB: Right. “Let’s get McEwan to do the Galapagos.”

IMcE: Exactly. Send him to…get him to talk to, wouldn’t it be good if we got him to talk with—the culture is very noisy with that. I have to employ someone to come in and just deal with all that.

RB: Some people find it fun, I guess.

IMcE: I’m not saying it isn’t fun. But I think you go nuts.

RB: Distracting.

IMcE: Yeah, if you want to be serious you have to just shrink back into your circle of friends, your family, and the work. And not be tempted out too much.

RB: I suppose one of the arguments for the bad effects of success.

IMcE: Yeah, it can be—often a lot of these things are quite attractive. “Would you like to come to some beautiful spot in southern Europe on an island and be given $10,000 and you just have to give a reading or 20 minutes also there will be this or that interesting person?” “Well, why not?” And the reason, “Why not?” you have not only to keep working but get out of the way of that light and heat. Otherwise you will never get yourself back again. [quietly almost whispers] You have to sort of retreat. I am not saying you have to become Pynchon or Salinger. They have the reverse problem. They are Osama bin Laden. On the run. So you have to do a certain amount—you don’t want to become a mystery that’s too interesting. But you do have to stay out of the way to keep your sanity.

RB: So I can assume that’s what’s next for you is to retreat from the heat and the light?

IMcE: That I will certainly do. Next Wednesday. I only finished Saturday in the beginning of December [2004]. I was really doing it right up to the wire. And four weeks later it was published in the U.K. and almost as soon as that was all over I’ve come over here. So I haven’t really had time—and I have rather enjoyed not having time—this is great. I am in the perfect mood for this kind of thing. Perfectly happy to talk about Saturday and anything else. So it’s a rather magical time, too, between books. Before I get too desperate about not writing—to read and do a bit of traveling. I have just been in the Arctic, down to Uruguay with my wife to see Martin. I got to Libya. I’m going to do some hiking in northwest Scotland. There will be a lot of that. But a lot of reading. Something will start to stir and I hope to be writing again by the end of the summer.

RB: Are you edgy when you aren’t writing?

IMcE: Yeah. I’ll begin to be. Not yet

RB: Is there a diagnosis?

IMcE: Unemployment, it’s called.

RB: Thanks. Well, we have to end. I hope when I see you in three or four years we get more time.