Impresario Seaman

Norman Seaman was one of New York’s great avant-garde supporters. In his biography, he said, John and Yoko would only get a chapter.

“The main thing about life,” Norman Seaman would say, “is to be playful.”

Seaman, who died last year at age 86, was in his seventies when he told me that. I was in my twenties. In many ways he was the more youthful one. He looked old—with his disheveled clothing, bushy white beard, and stooped shuffle, he was often mistaken for homeless—but he thought young. He was enchanted by the possibility of what might happen next. I was a struggling writer worried about rent.

In its obituary, The New York Times called Seaman a “niche impresario” who produced thousands of mostly classical concerts and a clutch of Off-Broadway plays from the start of his career in 1950 until his final years. The paper failed to mention it, but at the dawn of the ‘60s he emerged as an uptown representative for the avant-gardists whose experiments have come to be defined by the term Fluxus. (George Maciunas, who handled Fluxus matters downtown, was something of a rival.)

Yoko Ono met Seaman through her first husband, Toshi Ichiyanagi, a radical composer who had benefitted from Seaman’s ability to book artists in the Midtown recital halls that attracted reviewers from The New York Times, New York Herald Tribune, and other establishment publications. (It is a truism that in order to épater le bourgeoisie, you’ve got to reach them.) Ono was a fixture in the downtown loft and gallery scene, but she had hopes for greater things. “When I first explained to Norman about the show I wanted to do, he kept laughing,” she told me in an email. “Well, yes. The idea was so daring, I could see that the only way to take it seriously was by laughing—a not-so-oxymoron situation. After I explained the whole thing, he said, ‘Okay, let’s do it.’” She wanted to put on a multimedia event with dissonant music and provocative theatricality—dishes would be smashed, recordings of moans and wild laughter would be played, a performer would chant about counting the hairs on a dead child. In what he described as Ono’s debut—it garnered her first notice in the Times and Herald Tribune (which spelled her name wrong)—Norman presented a concert of three of her works at the 298-seat Carnegie (now Weill) Recital Hall on the third floor of the Carnegie Hall building on Nov. 24, 1961.

“I was not very happy because critics just made fun of it,” Ono recalled. “But somebody said, ‘Yoko, you’re reading it wrong. It says it was a full house. That’s the important message.’ “

To Norman, Ono was “original,” “beautiful in an unorthodox way,” and “somewhat insane.”

“She came into the perfect atmosphere for her and for me,” he told me. “I was representing the wildest people and she comes in, the wildest of the wild, ready to launch her career. She was ready to be exposed to the world and I was ready to take her on. That was the beginning.”

I first met Norman 14 years ago at an anemic dinner party that he jolted to life with a cascade of anecdotes, jokes, provocations, impressions, proclamations, and songs, all delivered in a distinctively New York accent that was both streetwise and erudite, like James Caan crossed with Isaiah Sheffer. His patter, which he maintained while devouring a large mound of food that tasted so much better because it was free, offered a beguiling glimpse of more than half a century of New York cultural life. He seemed to have a bottomless trove of stories about everyone who had ever performed a note or recited a line near a Manhattan concert hall.

Let’s put this in italics: He gave away his tickets. To ensure that his artists didn’t feel bad.

Noticing my interest and pronouncing us simpatico, Norman asked whether I would like to collaborate on his long-delayed memoirs, for which he had years ago secured some sort of agreement with Henry Holt (which he never could locate). I agreed, feeling I had stumbled upon a character with an intimate knowledge of New York’s lost worlds, a figure as original as any of the artists he represented. Over time I would come to see him as something more profound, an essential figure in any civilization. He was not only a presenter of artists, particularly of those yet to be acknowledged or prone to be dismissed, but he was devoted believer in the creative act. He lived for it. He thrived on it. It made him happy. During a concert at an outdoor fair in upstate New York two summers ago, David Amram, the classical and jazz composer who scored the classic Beat Generation film Pull My Daisy, pointed to Norman in the audience and called him “one of the great figures in American music” for taking risks on the promise of talent.

Seaman happened upon his career in show business. Upon returning home from service in World War II, he studied literature on the G.I. Bill and moved into the Yorkshire Residence Hotel at 113th Street and Broadway with his brother Eugene, a student at Julliard under the famed Rosina Lhevinne, the piano teacher of Van Cliburn, James Levine, John Williams, and hundreds of virtuosic others. They were great times. Whenever Gene played informally in the apartment with members of the New York Philharmonic who lived in the building, a spontaneous party would break out that would attract people from the street. When Seaman described the glorious scene to Madame Lhevinne, she scolded him for failing to seize an opportunity. “You foolish boy,” she said in her thick Russian accent. “Don’t you see there’s an audience here? You should hire a hall and let them pay something.”

He did. He put on five concerts during the doldrums of August 1950 before the fall season began—his brother’s debut was one—for next to nothing at the Carl Fischer (later Judson, now Cami) Recital Hall on West 57th Street, giving birth to what he dubbed “interval” concerts. Once the regular season started and the prime-time slots were filled by headlining artists, he snapped up the unused hours between 4 and 6 p.m. at bargain rates and called them “twilight” concerts.

Seaman came to specialize in producing the fabled “New York debut,” a necessary step in every aspiring recitalist’s career, particularly since he guaranteed a newspaper review (or a few) that could attract the attention of agents and managers. He once estimated that a third of all his concerts were debuts. What made him the king of the debut—and all kinds of productions that lacked obvious commercial viability—was his revolutionary policy of not charging artists for his services. Instead they would share in the profits, if there were any.

But there was never much of a profit. In fact, Seaman became the acknowledged master of “papering” a hall—filling the seats with patrons who hadn’t paid for tickets—which kept his performers from being dejected by the sight of empty rows, he told me. In 1960, the Times celebrated him as the “Impresario on $37.50,” the total cost of those first five concerts in 1950, and noted that his programs were “appallingly non-commerical.” Let’s put this in italics: He gave away his tickets. To ensure that his artists didn’t feel bad. Or nearly gave them away. For a nominal yearly fee, you could join his Concert/Theatre Club and gain entry to all of his shows (and to other producers’ poorly selling shows as well) by flashing your club card to the box office manager. (He once told me that Concert/Theatre Club dues represented the bulk of his take-home salary each year.) Seaman had established his own brand of cultural socialism—presenting uncommercial artists to mostly non-paying customers in prime Manhattan halls—that was guaranteed to keep him many floors from the penthouse suite. Instead, wrote the Times, “he and his wife, their several children, a prolific family of cats, and a beagle hound live in the jostling confusion of a thickly-populated section of the Bronx, and he rides the subway to a one-room office furnished chiefly with stacks of concert announcements and accumulations of other related papers.”

Lennon asked him for precise details on just what it felt like to be struck by a bullet.

But, oh, the legends he helped launch! He would often recite the names to me in the same mantralike order, singers like Shirley Verrett (soprano) and Martina Arroyo (spinto soprano), and instrumentalists like Igor Kipnis (harpsichord) and Robert Gerle (violin), all of whom became stars in the classical world of the ‘60s and ‘70s. He reveled in the splendid composers he had aided, mentioning Pulitzer Prize winners Charles Wuorinen, Shulamit Ran, and Gunther Schuller. According to his manager, Wuorinen recalls writing a score for an adaptation of Gertrude Stein’s Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights half a century ago, but doesn’t remember Seaman having any role in the matter. (Norman, for his part, described Wuorinen as “a young Columbia University student who I thought was very talented.”) “Yes, indeed,” wrote Ran in an email when I asked if Seaman produced her 1967 debut. “He was a decent man—not out for anyone’s money—in a field where there are plenty of sharks.” Gunther Schuller sounded wistful when I inquired about Seaman, who he recalled as someone scuffing around the edges of the concert halls who “wanted to be helpful and do good things.” Seaman put on an early-career concert of Schuller’s works that featured the premiere of his challenging Quartet for Double Basses, which had been declared unplayable but now was hailed by the critics. “It was a very important concert not only for me but for a certain kind of music,” Schuller said. Then there was Edward Albee. The advertisement that Seaman took out in the Times confirms that he produced Albee’s first work to appear on a professional stage, a long poem set to music, even if Albee now “has no recollection of Mr. Seaman,” according to a statement from Albee’s assistant.

“I remember Norman very well and it’s true that, during my long-forgotten sojourn at the Gray Lady of Forty-third Street, I often reviewed his concerts,” said Eric Salzman, the composer and author who was a music writer at the Times from 1958 to 1962. “He was the poor man’s Sol Hurok, the impresario for artists and music that were not being heard or recognized elsewhere.”

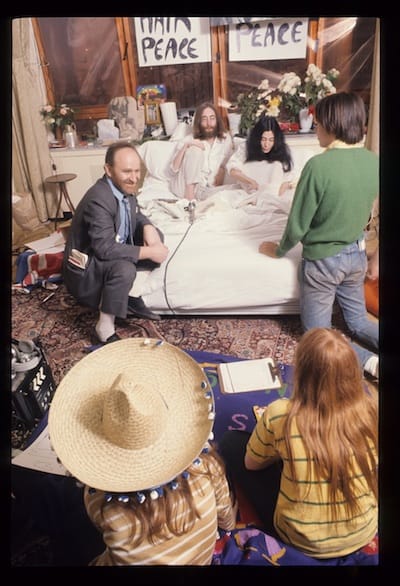

There would always be Yoko. In 1969, Seaman jetted up to Canada with his wife Helen and four teenage children to join Ono and John Lennon’s famous bed-in in Montreal. In the film taken in the room, on the 17th floor of the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, you can see Norman (and Timothy Leary, Tommy Smothers, and an assortment of Montrealers) singing joyously during the seminal recording of “Give Peace a Chance.” At another moment during the several-day event, a freelance photographer named Gerry Deiter, on assignment for Life (the story never ran), snapped a picture of Seaman perched on the edge of the couple’s bed, shining a grin toward the assembled media and guests—sitting, as it were, on top of the world. It is that rarest of photographs: It captures a person in the midst of experiencing something like metaphysical ecstasy.

Seaman and his family joined the couple’s inner circle, particularly after the Lennons moved to New York in 1971. The bond drew closer in the years after Sean’s birth in 1975. Helen was hired to be the boy’s live-in nanny and Norman was given a first-floor apartment in the Dakota to be close to his wife (who was staying in the family quarters on the seventh).

If most accounts of these years portray Lennon as a creatively sterile house-husband indulging in profligate drug use—see Goldman, Albert—Norman wanted to correct the record. Lennon was brilliant and engaged, “always reading and always interested in everything.” He told me that John would sometimes come down to his apartment to participate in what sounds like undergraduate bull sessions of the sort Lennon missed out on in Hamburg. They would discuss Noël Coward (whose records Norman gave him as a gift) and Jack London (who Norman had studied in graduate school). Lennon detailed his fascination with explorer Thor Heyerdahl’s 1947 trip across the Pacific Ocean on a primitive raft called the Kon-Tiki. “He had me read Kon-Tiki, and he had a big map on the wall showing the trajectory of that expedition,” he said. “He knew it inside and out.” Norman told me about a long conversation that explored the truths lurking in the seemingly trite lyrics of old standards like Sammy Fain’s “That Old Gang of Mine,” which described how marriage strains even the strongest of childhood friendships:

There goes Jack, there goes Jim

Down to Lover’s Lane.

Now and then we meet again

But they don’t seem the same.

“He said, ‘I like that song because it really hits the button. That’s what happened to the Beatles,’” Norman said.

If you go by the mini-library of works about the Lennons written over the last few decades—none of which he cooperated with—Seaman will forever be known for his suggestion of his nephew, Fred, for the post of Lennon’s personal assistant. In the months following Lennon’s assassination on Dec. 8, 1980, Fred Seaman took Lennon’s diaries and other items from the family’s residence without permission, eventually pleading guilty to second-degree larceny. The initial messiness led Ono to sever her ties with Norman and Helen even though they were never accused of wrongdoing. The Seamans were gone from the Dakota by 1982. In his conversations with me, Norman said he wanted to avoid publishing anything negative about Ono because of the upset it would cause his wife, who remained attached to young Sean.

I found it impossible to keep up with him. His memory was too photographic. His experiences too vast.

But his account of the Lennons would only take up one chapter in the book anyway, Norman said. There were lots of other topics to be covered. His years as an on-air announcer at WNYC. His role in helping smuggle fighter planes to Israel during the War of Independence in 1948. His brushes with violent death—he was shot during a traffic argument in front of Carnegie Hall, miraculously surviving two gunshot wounds from a .38 handgun. (Afterward Lennon asked him for precise details on just what it felt like to be struck by a bullet.) The stories were endless and impossible to corral. Digressions would be piled upon digressions. Norman had no illusions about his tendencies. He said he was opposed on principle to order and planning because it removed the playfulness from life. “Yeah, it’s good to have people who are dedicated social activists who want to build the world and all of that,” he said. “But I don’t think that rules out at the same time being playful. I mean, what the hell is life all about if you’re going to be a morose, unhappy, Dostoevskian character? So what if you are successful, quote, unquote? What the hell have you gotten?”

As the morose, Dostoevskian character who was attempting to create order amidst his chaos, I grew weary by spring 1998, the date of our tenth and last taped interview. I found it impossible to keep up with him. His memory was too photographic. His experiences too vast. When other projects with the promise of sure paychecks came along, our interview sessions came to an end. Instead he evolved into the oldest member of my circle of friends, the rumpled garden gnome at the barbecue bending ears about the play he was ready to produce. He was still producing concerts into the early aughts but his glory days had passed.

During his final years, Norman focused solely on his Concert/Theatre Club while caring for Helen, who had suffered a stroke. Yet when his daughter called to tell me he had died, I found the news hard to believe. It didn’t seem possible that such an animated corpus could lose its force. The world didn’t make much of a fuss over his passing. It appeared Norman was destined to be forgotten, just another name in tiny agate type in old newspapers. But I hope it’s not too sentimental of me to suggest that lots of artists do remember him, even if he reminds them of the time when they were scuffing around the edges of concert halls. Martina Arroyo, who went on to become a Metropolitan Opera diva after Norman produced her debut in 1957, had no trouble summoning his memory when I reached her on the phone. The reason was simple, she said. “The most important words that a young artist can hear are‚’I believe in you.’”