It’s Like This, Only

Language in Mumbai can be tricky for newcomers, especially foreigners trying to hail taxis.

It’s the end of a long night eating tandoori chicken and drinking Kingfisher beer in Mumbai with visiting friends. Traffic has slowed to a few cars here and there, and we flag down a cab. The stereo is pounding Bollywood disco, but the driver turns down the volume to ask where to. “Turner Road,” I reply, or, more accurately rendered, ““Tournah Rrrr-ooad” with several up-and-down vocal inflections. It’s a fake Indian accent so horrendous even a 10-year-old doing his best Apu impersonation would cringe.

“Why are you talking like that?” my friend stage-whispers.

“Because,” I say, still talking like a second-degree stereotype, “it’s the only goddamn way we’ll get home.”

See, Turner Road does not exist in Bombay. But “Tournah Rrrr-ooad” does, and, without blinking an eye, the driver steps on the gas.

Like most Americans, I was raised not to hit people, stare at the handicapped, or make fun of accents. In my first months in Mumbai, it felt wrong to spit out “Tournah Rrr-ooad;” not deliciously wrong, transgressively wrong, but really wrong, on par with pulling back the corners of my eyes and babbling about “flied lice.”

Still, when I tried to give cab drivers directions in American-English, I’d repeat my destination five, six, or 20 times. But if I sheepishly eeked out an “Indian” pronunciation, it worked like a charm.

Over time, I became used to it. I dropped my politically correct inhibitions and got down to getting around. A lot of things have been like that for me in India—trading in sensitivities for accomplishing stuff—especially when it comes to language.

Mumbai exists in the state of Maharashtra. Maharashtrians speak Marathi and make up around 30 percent of the city’s population. The other 70 recent has roots all over India—from Uttar Pradesh, where they speak Hindi, to Goa, where they speak Konkani, to Assam, where they speak… Assamese. These are languages that, for the most part, are strangers at the party; Gujarati to a Telegu-speaker is as incomprehensible as Wolof to an Italian, or Marathi to an American, for that matter.

Needing to know Marathi in Mumbai is like learning Dutch to pass in Manhattan; technically it’s where the city started, but we’re way past that now.

To survive, Mumbaikers rely on English and Hindi as their lingua franca. Language is a class divider: the most educated people speak English, Hindi, and their mother-tongue, maybe with Marathi thrown in for regional kicks, where less-educated people speak only Hindi and their mother-tongue, and the very lowest classes speak only their mother-tongue, effectively cutting them off from the rest of the city.

When I first learned I was being assigned to India, I assumed Hindi was the language to learn. Friends were quick to correct me: “They don’t speak Hindi in Mumbai. They speak Marathi. You should study that.” So I desultorily returned my Hindi books to the public library and, finding no equivalent “Teach Yourself Marathi” guides, sat and bided my time. Of course, it took me only two weeks in Bombay before I realized I’d been right all along: needing to know Marathi in Mumbai is like learning Dutch to pass in Manhattan; technically it’s where the city started, but we’re way past that now.

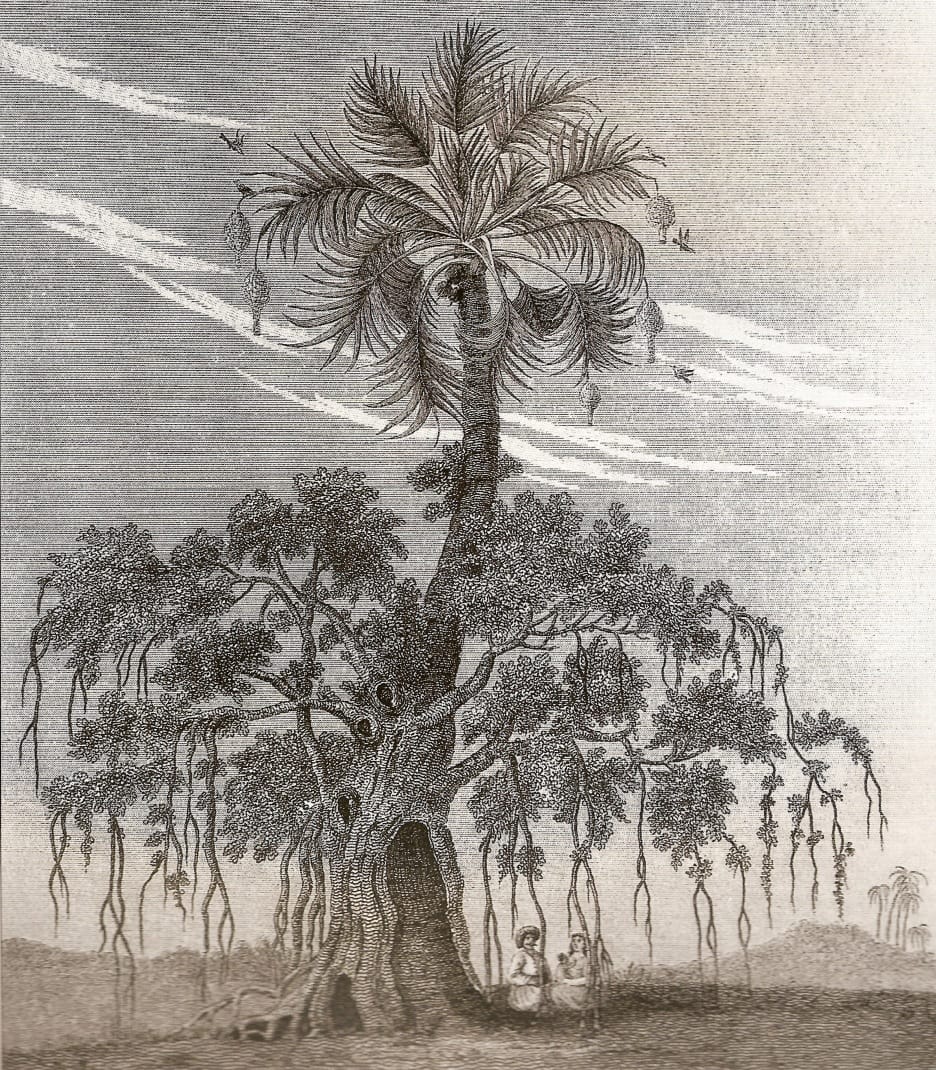

My instinct also proved to be right when it came to the name of the city. Somewhere in my mind, “Bombay” has always been the exciting, exotic capital of India, a city of slums, and palm trees, and elephants—never mind that its name isn’t “Bombay” and it isn’t the capital. However, my politically correct Western-mind told me to side with “Mumbai,” the city’s Marathi name. “Bombay” was romantic, to be sure, but it also reeked of pith helmets and gin.

But most Mumbaikers are happy to call their city “Bombay;” that’s been the city’s name for, say, all of its history. It’s a certain right-wing political party—the Shiv Sena—that pushed for the name change—a certain political party that doesn’t like non-Maharashtrians “invading” their city and calling it by a “foreign” name.

Now, like most Bombayites, I slip back and forth between the two choices. I ask my friends to meet me in South Bombay, but then I’m running late, so we meet in the middle of Mumbai. It took some guts to do it at first, like the first time I re-christened my neighborhood “Baaaahndra” from “Bandra,” but the Bombay/Mumbai mix gets fewer stares and feels more natural.

The English spoken in Mumbai is, to my ears, nothing short of fantastic. It is a loopy, sing-song spaghetti mess with odd accents, quick flicks of the tongue, and excessive nasalization. Veg becomes wedge, Jil becomes gel, and films, flims.

The words themselves are enamoring. Indian English is stuck in a time warp—the problem is no one can figure out exactly which decade, or what century. A casual business email from a local colleague concludes, “The details will be intimated presently. Please do the needful. Most respectfully yours.” Wikipedia claims overly formal language is a holdover from the East India Company, but I think that’s a bit generous, even though certainly the language has more in common with letters my grandfather wrote than texts I send my friends. If “updation,” “prepone,” and “felicitate” aren’t already in your office vocabulary, they really should be.

“It is there only.” “It will come tomorrow itself.” “After the divorce, he went and killed himself only.”

I’ve found the best way into the hearts and minds of my Indian friends is through slang. The essential trifecta of Bombay slang is “arre,” (hey!), “yaar,” (dude), and “na?,” tacked on the end of a sentence to mean, “right?”

Arre, yaar, that film strike means no movie this weekend, na?

Advanced slang means knowing when to replace “yaar” with “boss.” “Boss” is a formal “dude,” best used with waiters, taxi drivers, and guys on the street you ask for directions. Advanced slang also means knowing your curse words and their appropriate execution. I’m working on my repertoire, but even 15 seconds of practicing with a colleague creates peals of work-disruptive laughter. My favorite insult so far is to call your enemy your “brother-in-law.” It’s subtle; it took me about six months to realize that if he’s your brother-in-law, why, then you’re sleeping with his sister! Ouch.

The most difficult element of Bombay English to master comes from a tiny syllable—bhi or hi—that is inserted in to Hindi sentences to emphasize the word preceding it. In “red hi hat hai,” it’s the red hat (not the blue), while in “red hat hi hai,” it’s the red hat (not the shirt).

The problem—if you consider it a problem, which you probably don’t, unless you tried this morning like me to catch a taxi, only, to the office itself—is that people aren’t content to simply translate bhi and hi as increased stress on the word. They also translate “bhi” or “hi” as “only” or “itself;” e.g., it’s the red hat only. You probably have no idea what I’m talking about, but anyone who has been to India does.

“It is there only.” “It will come tomorrow itself.” “After the divorce, he went and killed himself only.”

At the beginning, going around, everyone I met sounded defensive. “How many kids do you have?” “Three, only.” Ok, jeez. Chill out.

Then I started to use it myself. I recently took my maid on an expedition to show her my dry cleaner. After we had trekked across three traffic lanes on a hot and humid day, I stretched out my hand and proudly declared, “It is here, only!”

She looked at me with a smile and bobbled her head.

Oh yes, the Indian head bobble. Did I forget the bobble? Telling a cab driver “Tournah Rrrr-ooad” will get you nowhere unless you also insert the appropriate head waggle and/or bobble. The head bobble speaks volumes, but that is a Bombay discussion for another day.