Before returning to Canada, I will stay for two nights at my cousin Nanaji’s incredible penthouse apartment in the Bombay hills. Nanaji, one of my favorite relatives, is vice president of the family auto-glass firm, but sadly he’s away on business for my visit; as such, he has dispatched staff to meet me at the airport.

The man holding the MALL.A. sign is Nanaji’s driver, Ravi. As far as I can tell, Ravi is the exact same human being as my aunt’s driver, Raju (same moustache, bulbous gut, eager head-wobbling), with one exception: He runs everywhere. From the moment we step out of the airport, my backpack slung over his shoulder, he is sprinting uphill to the car. I’m tired; it’s hard to keep up. Why is he running? Are we being chased?

My tour of Bombay on the way back to my cousin’s place is of the new luxury hotels that are springing up as a result of the steady influx of foreign businessmen. “This one, Sheraton,” says Ravi, pointing out the window of my cousin’s SUV as we drive by. I get the feeling he’s done this before. “This one, Marriott.” I can think of nothing else to say but: “Great.”

We run from the parking garage into the elevator, which takes us up to Nanaji’s apartment. On the marble kitchen countertop, I discover that my cousin has left me 3,000 rupees and a note: “Enjoy yourself.” By this point in my trip, my credit card is maxed out and my bank account overdrawn, so the money, while overly generous, goes directly into my wallet without a second thought.

Later, at sunset, I go up onto the roof to look out over Bombay. To the north, there is something like a mini-golf course scattered between palm trees. Huge apartment towers sprout out of the land on either side, one wrapped in a rickety exoskeleton of bamboo scaffolding. South is the commercial district, and beyond that the hills, on the far side of which a shanty town balances precariously, all tarpaulin and tin shacks stacked in rows, like building blocks laid out by a child.

After nearly a month, I am tired of India. All I want to do is sit in my cousin’s condo and wait to leave. But with only one day in Bombay I can’t let my dad down; he’s informed me that a visit to the National Gallery of Modern Art is compulsory. So I go; Ravi drives. An exhibit on Gandhi is showing, and after my standard “Indian or foreigner” argument with the ticket-seller (which, this time, I triumphantly win, allowing me inside with 2,995 of my cousin’s rupees to spare), I am inside.

Each section of the exhibit is staffed by student guides dressed identically in simple, rough-hewn cotton shirts. Most of the guides have memorized a script they recite listlessly, without variation, to visitors. The exhibit itself combines fascinating trivia and archival material with needlessly complex technology. One piece, up a staircase, is a cube barred with holographic lasers. “This is an E-prison,” the guide narrates. “E-prison means? Electronic prison.”

Instead of a single waiter, a team of three men is assigned to our table. Is this what a maharaja feels like? I’d imagine so. I trudge around the museum, past a harp shaped like India with Gandhi’s instantly recognizable ears protruding from either side (the strings are also lasers; you “strum” them and Gandhian sound-bites play), past a display that plots the cross-country train voyage young Mohandas undertook upon his return from Africa; this comprises a railcar and some sort of interactive display I can’t be bothered to operate.

I move next to a coffin-looking thing inset with a series of television screens—beside which a young guide stands beaming at me. He is maybe 19, slender, very tidy, eager. “This is a timeline of Gandhiji,” he says. “My name is Rohit. Where are you from?”

“Canada.”

“I am from India. Would you like to see the timeline?”

What follows is nothing short of remarkable. A slider moves along a track on the display, and at each of the dates on the Gandhi chronology a video plays—although this is not what amazes me. Rohit supplements the on-screen narration, and what he has to say (anecdotes, asides, corrections) is infinitely more compelling and thorough than the voice-over. He speaks with passion and energy; the kid knows everything about Gandhi, and it’s obvious he admires the father of India’s independence very much.

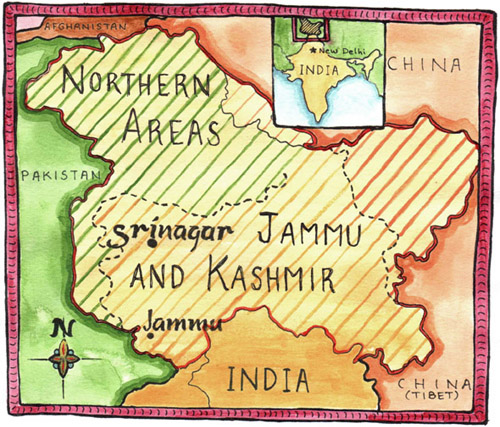

While I’m not the expert that Rohit is, I’m a bit more skeptical. There are contradictions between the direction Gandhi foresaw for the country (religious, agricultural) and where it has ended up, a result of the early industrialization encouraged by India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, a Kashmiri. India’s problems aside, it would be hard to argue that the country’s newfound prosperity would have been possible under Gandhi’s vision.

When the display ends with Gandhi’s murder, Rohit looks sad. The screen fades to black and he turns to me, his hands behind his back. “It is important that young people understand Gandhiji’s message. India is shining in the world, but it is a place filled with bad values. We must live humbly, get along, not be consumed by greed.”

There is a cute young woman—a foreigner, with the wide-eyed enthusiasm and unshaven legs typical of the backpacker—waiting to see the timeline, so I avoid confronting Rohit with my skepticism; regardless, his enthusiasm is admirable, his hope encouraging. As Rohit begins his spiel again, I move on to the next piece in the exhibit. This one is a video of a Qawwali concert triggered by walking through the path of yet another laser. On screen, four men sit together on a dais in a mosque, performing the haunting and riveting music of Sufism, a mystic branch of Islam. I stop to watch, and listen.

The music is comparable to the Kashmiri music that the band played at my cousin’s wedding. The instruments are similar, as is the call-and-response and intense, accelerating percussion over the drone of harmonium. The camera spins slowly; the musicians’ song swells. I think about the time my dad went to see Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Qawwali’s biggest name, and a member of the audience became so enraptured by the music that he went into a trance and fell from the balcony. On the video screen, the singers sing and play. They are amazing. Out of nowhere, something hardens in my throat. My eyes tear up. This actually happens.

But then the cute backpacker is standing beside me, so I check myself. We watch the video. I tell her my dad’s story. She laughs and introduces herself as Summer; Summer is Australian and backpacking around India. Sensing an opening, I ask her if she’d like to go to lunch with me. “I have a driver waiting outside,” I explain, awesomely.

Ravi spots us as we emerge from the museum, waves, and then is off. We chase him to the waiting car, where we catch our breath and try to decide what to eat. I remember my cousin’s donation and instructions, so I suggest the legendary Taj Hotel, birthplace of butter chicken. Summer has dreamed of eating there. “Can we afford it?” she wonders. “No problem,” I scoff, Nanaji’s wad bulging in my pocket. “It’s on me.”

The Taj is lavish, all marble archways and palm trees and gold trim. Elephant sculptures figure heavily. Out the window of the restaurant is the Gateway of India, looming over the harbor. Instead of a single waiter, a team of three men is assigned to our table. Their first task is to help us wash our hands: One pours water from a golden urn, one collects the run-off in a golden dish, and one stands waiting with towels. There is a lot of bowing throughout the entire process. Is this what a maharaja feels like? I’d imagine so.

We begin the drive up through Bombay to my cousin’s apartment. I realize that from this point on I am beginning my journey home. We order butter chicken, bhindi, aloo gobi, naan, paneer, gigantic beers. The food is outstanding. Summer is enjoying herself, as am I. We eat and drink, order more beers. When the dishes are emptied we sit back, agreeing that it’s the best Indian food we’ve ever had. Then the bill comes. Summer makes a move for it, but I wave her hand away. I have never felt so awesome—until I discover that, despite my cousin’s financial aid, I’m at least 500 rupees short, and that’s without leaving a tip for our doting servers.

By the time Summer comes back from the ATM, cash in hand, I am feeling markedly less amazing. The 800 rupees she ends up contributing, she lets me know, is about ten times what she’s spent on any other meal during her six months in India. I apologize. I am still apologizing when I follow her to the parking lot, wondering if Ravi can drop her off anywhere. “I’m going back to my hostel,” she tells me. “Don’t worry about it.”

On the way back to Nanaji’s, Ravi suggests visiting the Mani Bhavan Gandhi Museum, located in the house where Gandhi stayed whenever he was in Bombay. Not wanting to offend my cousin’s driver, I agree.

The museum is a modest, two-story building undergoing some fairly major renovations. Most of the downstairs level is closed, but the second floor, including a room featuring a series of biographical dioramas, is open to the public. The dioramas are what you’d expect: humble, cute, vaguely embarrassing tableaux of scenes familiar to me from Sir Richard Attenborough’s film, including the horrific Jallianwala Bagh massacre at which 379 unarmed Indian civilians were gunned down by the British Army in 1919.

This is the cabinet I am standing beside when a group of middle-aged, British businessmen enter the room. There are maybe six of them, led by an Indian guide. I’m not sure if it’s the context or not, but to me the businessmen seem obnoxiously disinterested. They drift from one diorama to the next, checking their cellphones and PDAs, muttering to one another. I want to grab the pinkest, fattest one by the jowls and shake him and scream, “Pay attention, you stupid motherfucker! Your people made this necessary!” And then, instead of resorting to any further violence, I’d apply the pacifist, Gandhian principle of satyagraha and take my leave.

Of course, all I do is take my leave. I slip out of the room and down the hall, where Gandhi’s bedroom has been preserved as he left it. The room consists of a sleeping mat, a simple dhoti and a spinning wheel—the central image on the Indian flag. Looking into the bedroom of one of the greatest men in history, I try to have a moment. I want my trip to culminate here in something significant: an epiphany cast in a ray of sunlight from the heavens. But I wait and nothing comes.

On my way out of the museum, I pass the businessmen again. They are in front of the diorama of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. The looks on their faces are severe, hushed, reverential. The fat one is shaking his head as the guide details the gruesome events. It is obvious that none of them has ever heard this story before. They are rapt. They look horrified and ashamed.

But then I am outside, sprinting down the street after Ravi on our way to the car. When I get in and we begin the drive up through Bombay to my cousin’s apartment, I realize that I am essentially, from this point on, beginning my journey home.

Back at Nanaji’s house, packing my things, I start to worry that it’s my last night in India and I still haven’t come up with anything significant from my trip. I haven’t learned anything, really, about Kashmir. I don’t feel any more worthy of being “the last of the Mallas” after being here for a month than I did before I came. If anything, I’m more of an outsider: not part of the crush of young elite barreling into the future, and not like Rohit, either, with a clear view of the past.

The next morning, Ravi drives me to the airport. As we turn onto one of Bombay’s sleek new expressways, a billboard for some ambiguously technological company boasts, “Marching Toward Excellence.” This seems an apt articulation of India itself these days—an army of snappily dressed urbanites, briefcases in one hand and MBAs in the other, parading toward some approximation of success. But then there are young guys like Rohit. How do Gandhi’s comparably parochial ideals—on which the country’s independence were built—figure into the future?

I will leave India not with answers, but more questions than I had before I came. This country is too complex, too full of contradictions and anomalies, to even begin to understand it in under a month. That I came here with the expectation of gaining cultural, let alone personal, enlightenment has proven ridiculous. Instead, like India itself, I feel flanked by my family’s past and future; the present, where I am caught, is nothing more than what happens in between.

So, I have nothing of substance to go home with—and tomorrow, I will leave. But very soon, I know I must come back.