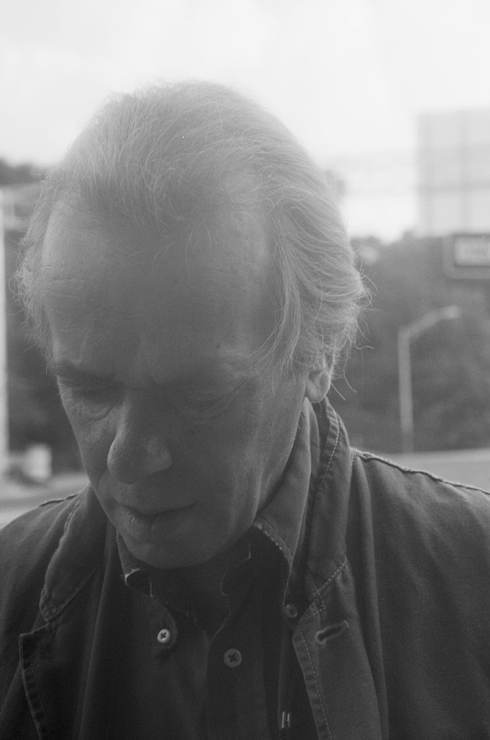

Martin Amis, Redux

Our man in Boston sits down with Martin Amis for their sixth chat to discuss Nabokov, dictionaries, spiteful reviews, the death of Christopher Hitchens, and the freedom of writing fiction.

In preparation for my sixth conversation with Martin Amis since the publication of his novel Time’s Arrow in 1991, I read his newest opus, Lionel Asbo, and an endless skein of interviews, commentaries, and gossipy tidbits, plus his recent reportage for his old pal Tina Brown’s Newsweek.

Off camera I suggested to Martin that he was the most interviewed writer in the world—e.g., here’s our 2007 chat—to which he demurred, offering his pal Salman Rushdie as the holder of that title. In any case, in the recent filings on Amis you might learn about the demise of his tennis game, the reason for his move to Brooklyn, his feelings about the USA, the profound loss of his friend Christopher Hitchens, that he loves dictionaries and thesauruses, and the fact that one’s vocabulary shrinks with age. All of which you will find in some iteration in the conversation that follows.

One thing that should come through is that Martin Amis, scion of Kingsley Amis (Lucky Jim), is the quintessential writer. He talks, walks, observes, and looks like a writer. Which would make him the perfect dinner party guest for the best kind of evening of non-sexual entertainment. Martin is as always an engaging conversationalist—I am looking forward to a few more chats with him, as well as some splendid literary adventures.

Robert Birnbaum: Are you done with tennis? Writing about something like the U.S. Open?

Martin Amis: My interest in tennis peaked when I was a player. It’s been decreasing for quite a while.

RB: So no one can coax you onto a tennis court?

MA: Well, I got through the summer without playing even though we have a court in the garden.

RB: (laughs)

MA: So, maybe not. No.

RB: Maybe you can convert the court to another use.

MA: Well, no other people use it—not me.

RB: Nice. Are you in a position, when you decide you want to cover something, to send feelers out and get the assignment?

MA: Yeah.

RB: Are you ever rejected?

MA: No.

RB: Is that nice?

MA: Yes, it is but I mean, I’ve been able to do that for a while. You have to find the right magazine that [one’s idea] would appeal to.

RB: You wouldn’t approach editors you don’t know?

I enjoy reportage, and it’s quite easy, but writing an essay is murder. It’s the hardest thing you do. I much prefer writing fiction. Getting out of bed when all I got to do is write fiction is heaven.

MA: Well, I wouldn’t do the approaching. Sometimes you bring it about to mug up on a subject you are going to use in fiction. I did that with the pornography industry for Yellow Dog. And also the Royal Family for Yellow Dog as well. It means you write a long book review. Or you are sent to California and go to San Fernando Valley just to mug up. What’s good about that is, you reach your conclusions as a journalist, but when you come to write the novel, with luck there is always leg of understanding that will arise in the course of writing a novel. Because a different part of the mind is being used for a novel.

RB: You don’t have any disdain for journalism—you enjoy journalism and fiction. Are they different kinds of writing?

MA: Oh yeah, totally different. I enjoy reportage, and it’s quite easy, but writing an essay is murder. It’s the hardest thing you do. I much prefer writing fiction. Getting out of bed when all I got to do is write fiction is heaven. When it’s a piece to finish or to start I feel much more like a galley slave. As Gore Vidal said, “It’s writing left-handed.” If you are a novelist, the other stuff is left-handed—a left-handed gun.

RB: When you do journalism you have to answer to more people.

MA: Yeah, you don’t have the infinite freedom you have writing fiction.

RB: Fact-checking—

MA: Fact-checking. Deadlines. No one does that with—fiction is freedom. And the other stuff isn’t free.

RB: I take it you are still enjoying fiction.

MA: Yeah, more than ever. I know more what I am doing now. But it still astonishes me—Mailer was right to call that book The Spooky Art. A very good book it is, too. It is spooky the way things emerge in a sort of semi-dream-like state sometimes. And it’s amazing the way novels resolve themselves. In that moment when you can see the ending, say, when you are 250 pages in and the next day you are wondering, Where’s it going to go finally? And maybe the next day, you’ll see the ending. It’s like climbing a mountain. It’s [the ending] still a long way off but you can see it.

RB: At that point, you are confident that you will get there?

MA: Oh yeah. That’s why it’s such an important moment. You see how it’s all going to be wrapped up. And then you have to go through it again and make that culmination more of a culmination, have more things pointing toward it. I am writing what I think is going to be a short novel about the Holocaust, and I had my opening scene, and that was sort of part of the frisson of the idea. But I had no idea what was going to happen once I got that scene out of the way—

RB: Let me get clear on the sequence. Did you say, “I want to write a book about the Holocaust,” or did you have an image of this scene, imagine this scene, which then prompted you to write about the Holocaust?

I don’t get on too well with my early stuff.

MA: Well, this is the spooky bit. Something happens and it’s—Nabokov said, “The first throb of Lolita went through me” when he read an account in a French newspaper of a monkey that had been taught to draw, and all the drawing consisted of were the bars of its cage. That was Lolita. Seems so tangential, doesn’t it?

RB: Indeed.

MA: But I believe it.

RB: Was he asked to explain the connection?

MA: Well, there are lots of animals in Lolita, and there are monkeys, charming monkeys, and lots of great dogs. But that sounds more mysterious than most. An opening moment or scene with the Holocaust novel I am doing now, I wanted to—someone falling in what seems like love at first sight in Auschwitz. And the woman is the commandant’s wife and the man is a rather mysterious guy from Berlin who is the nephew of Martin Bormann. And those secondary ideas came up. But then I started it and wrote a 12-page chapter and I thought, It needs another narrator. Maybe two other narrators. So then, a chapter narrated by the commandant. And them I thought, Another narrator, but a smaller one. And that is the leader of the Sonderkommando—do you know what they were?

RB: Yes.

MA: What a job, eh?

RB: There was another unit that did something else [as odious], I can’t now remember.

MA: In the camps?

RB: Yeah. I can’t now remember, I might have come across it in a novel called City of Women.

MA: Primo Levi has a chapter in The Drowned and the Saved called “The Grey Zone,” and he writes of the Sonderkommando. [Mordechai] Chaim Rumkowski, you know him, the elder of—the Warsaw Ghetto? No, the Lodz ghetto—who was a crazy old guy who went around in a carriage with a starving horse leading him. And he had postage stamps made up of his face—he was a megalomaniac. And he was also a kind of collaborator. As they all were—had to be. He [Levi] does those in the same chapter. He says the Nazis didn’t ennoble the people, they ruined; they brought them into their own sick circle.

RB: They ruined them to the nth degree.

MA: Yeah, to the nth degree.

RB: I was having a conversation earlier today about the pianist Keith Jarrett. He recorded a solo concert released as The Köln Concert that I believe is his finest piece of work, which got me to thinking about how artists judge their own work. In your case, is there one of your books, perhaps an early work, that in your own assessment stands at a high mark? Perhaps you say to yourself, “I’ll never do better than this.”

You get senile mix-ups. You can’t think of the word “ventriloquism,” or you can’t remember that lady South African novelist who won the Nobel Prize. Nadine Gordimer, of course. I went for weeks without being able to remember her name.

MA: Um, I don’t get on too well with my early stuff.

RB: (Chuckles)

MA: It’s too crude. And too promiscuous, using slang that is kind of dated the day you write it. So the latest stuff is the stuff I like—purer to my ear.

RB: Could it be that when you complete a book you believe it’s the best book that you have written to date?

MA: Yeah, invariably, yeah. (Both laugh) So far, yeah. [pause] I mean when I do look at Money, and find a good page, I think, “Christ, it was coming pretty thick and fast when I was writing this.” But that’s true, and your music does get more muted, but your technique gets better, and so it’s a tradeoff. But as novels, the later ones are much more together.

RB: I read you quoted as claiming that one’s vocabulary shrinks as one gets older.

MA: Yes, that’s just a fact.

RB: How was that determined?

MA: It’s just a fact. Ah, there are horrible statistics to show it. (Both laugh). But I have always been a great user of dictionaries, and thesauruses as well. People get the wrong idea about a novelist and the thesaurus. You are not looking for words like “sinecure.” What you are looking for, most of the time, is a synonym that scans differently. So you need a three-syllable synonym, or one that doesn’t end in “-ation.” It’s just for the euphony. Um, but the COD [Concise Oxford Dictionary] is all you need. You look up a word, maybe a word you know perfectly well, and you see what it’s origin was, and that word is now stamped. It’s your word. And every time I do it, if feels like a gray cell has been born in my head; instead of going out, it’s coming in.

RB: So as you look up words now, you are retaining them?

MA: Yeah.

RB: But the ones you looked up 20 or 30 years ago you have lost?

MA: You won’t remember the origin. Although you get senile mix-ups—you can’t think of the word “ventriloquism,” or you can’t remember that lady South African novelist who won the Nobel Prize. Nadine Gordimer, of course. I went for weeks without being able to remember her name.

RB: Isn’t that a trick of memory? Is it possible that we don’t forget anything? It’s the recall that may be a problem—that the proper trigger will loosen our recall of some person or event.

MA: Well, you know the Borges short story about that, Funes, the Memorious?

RB: No, I don’t.

MA: I mean, it’s a beautiful story. He can remember that cloud, 30 years ago. And it’s a very funny story too. But he dies of coronary thrombosis at the age of 32. So it’s good that things rot away as well. I feel intellectually as good as ever. Better than ever. And I feel also that prose has to be worked harder on than it used to.

RB: I think you maybe the most interviewed writer in the world [Amis demurs, saying that Rushdie is]—I am surprised that the University of Mississippi, which has a series of volumes on contemporary writers called “Conversations with…”, hasn’t done a volume on you.

My writer friends—we don’t really tend to talk books. We might talk about books we read recently. We don’t talk about theory.

MA: There is no shortage of them.

RB: Anyway, in the immense library of interviews with you, are you thinking out loud or testing some ideas in those chats?

MA: I get—maybe it’s just the time of life. Certain things strike me as true, and why didn’t I know them before? For instance, I did a piece on Don Delillo for the New Yorker a few months ago, and I was thinking to myself, I only like about half of Delillo’s [work]. I like him a lot, but I only like half. And I thought, That’s true of everything.

RB: (Laughs)

MA: Uh, and actually half is [something] doing very well. Why should we like it? And we don’t. And that’s true of Milton, true of Shakespeare, true of Jane Austen. It’s true of everyone. Some have a higher success rate than others. I think Nabokov is pretty extraordinary—something like 13 out of 19, fantastically good. But true and obvious, in a way. But only thought of a year ago.

RB: Are the frequent conversations and interviews that are published an entirely different activity that you are engaged in and that engages you?

MA: Not really. The people I talk to about all this are family, my sons and my wife. And the girls—my younger daughters—I can see that there is going to be a lot of that kind of chat with them. But I don’t go to salons. My writer friends—we don’t really tend to talk books. We might talk about books we read recently. We don’t talk about theory.

RB: In one of your recent interviews you stated that you were very pleased with the readers that you have developed.

MA: Yeah, yeah, that’s—

RB: How do you know?

MA: You just get a sense of it—from the letters you get, and at a reading you look into the faces—

RB: And people buy your books.

MA: Yeah, there’s that. They read them, that’s the thing. I mean, they feel about you what you feel about Saul Bellow or Nabokov. Here is one for me. Here is someone whose every word I will read. Here is another thing that has only occurred to me recently. This vexing question of posterity. When I talked about this with my father, he said, “Posterity is of no fucking use to me! I won’t be here, will I?” That’s what’s so great about this: It keeps you honest, really. That’s all that matters—how long you last is all that matters. The only measurement there is.

RB: You used to say that you were writing for posterity, didn’t you?

MA: Yeah, the quest for immortality is universal. That’s why we have children and that’s why we write books. But what fills my eyes with nonsexual lust is at a reading where I see these young people. So I will live—

RB: Fifty years or so longer.

MA: Yeah, yeah. Exactly. And their youth enspirits you.

RB: For quite a while I have been fond of pointing out that instead of referring to Martin Amis as the “Mick Jagger of literature,” it might be more felicitous to refer to Jagger as the “Martin Amis of rock ’n’ roll.”

MA: Yeah, I have been asking that too.

RB: (laughs)

MA: Baffling, isn’t?

RB: You have been reported as saying that a “particularly English phenomenon was that people of no particular distinction achieved celebrity and then thought they were entitled to it.”

MA: Yeah.

RB: Doesn’t that also take place in the U.S.?

MA: Yeah it does. There doesn’t seem to be the volume. Maybe it’s all on TV—you don’t have three or four newspapers every day. The New York Post looks like the Partisan Review compared to the Sun.

RB: A minor point confused me—in one profile of you, you were doing the Times crossword puzzle in the New York Post?

MA: It carries the Times—

RB: Oh, the London Times.

MA: You see it’s not a moron crossword puzzle, like the New York Times.

RB: (laughs)

MA: “Big name in baked beans,” five letters: That’s not a crossword. It’s a general knowledge—

The longer a thing is the more it takes out of you. It gets to be physically painful, holding it all in your head as you are coming to the very end. And a short novel is a joy compared—I still like the big novels but there is something about taking it on.

RB: Speaking of which, you are now a U.S. resident. How long do you intend to stay?

MA: Um, it was all to do with family. My mother-in-law is what it depends on. And my wife’s stepfather of 40 years died before we got here. So it’s all mortality. My mother died two years ago and that’s just got to sink in.

RB: Have you thought past what ever your tenure in the U.S. will be? Another destination.

MA: No, I think we will be here, because our girls have school here. Certainly till the end of their education.

RB: I think Uruguay was the place to be. Something close to an idyllic state. Why you would ever leave there?

MA: The schools down there are more like play schools.

RB: Catholic schools?

MA: It’s not—although abortion is about the only thing that is illegal in Uruguay, religion is not a huge thing there.

RB: Other than the forays into journalism and your novels, are you interested in teaching?

MA: I taught for four years in Manchester and wouldn’t have given it up except we moved here. And that was really enjoyable, very nice to feel there is something else you can do that you enjoy and gives satisfaction. Um, but at 63 the future is—diminishing.

RB: Yeah, tomorrow is promised to no one. I said that to my son and he acted as if that was a revelation.

MA: Cuba? How old is he? He must be getting on.

RB: Almost 15. He’s playing freshman football—he’s a big boy.

MA: My older son is staying with us—he’s 6'3".

RB: Astounding—whose genes are those?

MA: Well, his mother had some very tall people in the family.

RB: Speaking of a diminished future, Richard Ford said after his Lay of the Land that he didn’t think he was going to write another novel. Since the men in his family seemed to die young, he was afraid of starting something he might not be able to finish.

MA: Maybe it was another long novel. Richard is fit as a fiddle.

RB: (Laughs)

MA: I saw him just after he finished The Lay of the Land and he was exhausted. There is no question that the longer a thing is the more it takes out of you. It gets to be physically painful, holding it all in your head as you are coming to the very end. And a short novel is a joy compared—I still like the big novels but there is something about taking it on. Canada, his new one, is quite long.

RB: Apparently, he got a second wind. I’ve been impressed that your more thoughtful reviewers seem to know everything you have ever written and can quote extensively from any and all of your novels.

MA: Some of them, yeah. This is the truth—you won’t believe it: I have more or less stopped reading reviews. It’s because you are always on to another thing, and that’s what you are interested in. And whenever I read a review, even if it’s good, there is always something that’s wrong. And then it’s in your head for a bit. And I don’t want that.

RB: I don’t read many reviews. Except as a thing unto itself—if I know the reviewer to have had original ideas and a way with prose—in other words, just a piece of good writing. There was a recent review in the New York Times by William Giraldi that generated some fuss by the reviewed author’s partisans, because it was claimed that the review was nasty and that the reviewer was showing off. The only nastiness, I thought, was that the book didn’t come off well.

MA: Yeah, but what point are you making?

RB: That the expectation seems to be that reviews must be positive, unless you have a personal grudge that you are settling—which, it appears, is an appealing point to some editors. One is expected to salute the effort—that just having written a novel is worthy of commendation.

MA: I believe that. I think the destructive review—I have written a few of them, when I was younger—it’s a youthful corruption of power. You are 25 and have the fate of book in your hand, and it goes to your head a bit. Um, but now I wouldn’t, if I dislike a book review it. And it’s true—someone gave everything they had for two or three years to write this book. And reviewers, I think they do write hostile reviews—it’s to do with whether it rubs them the right way or not. It has nothing to do with quality of prose, or whether they don’t like your attitude to this or to that.

RB: What could be more subjective? Of course when the reviewer quotes some leaden prose, which may be out of context—

MA: Quotes are everything. You might as well be talking to the wall if you don’t quote. You’ve got to quote. I said that to my son, who’s done some reviews. He said, “Dad, you can’t quote when you have 900 words.”

To accuse the writer of being egotistical is like accusing a professional boxer of being aggressive. You wouldn’t be doing it if you weren’t. But I still think there is something gross about it.

RB: Seven hundred to 900 words is a kind of degradation in itself.

MA: Well, there have always been 900-word pieces, but you do need a bit of space, and you do need to be able to quote. Then it becomes a reasonable and civilized undertaking.

RB: Peter Dexter, among other writers I have talked to, said the same thing—he gives credit to anyone for trying. And they care very much about it, too. It’s frightening how much they care. It’s amusing to see the attacks on negative/hostile reviews invariably accuse the reviewer of showing off, of narcissism or egotism. Which writers aren’t egotistical?

MA: Yeah, to accuse the writer of being egotistical is like accusing a professional boxer of being aggressive. You wouldn’t be doing it if you weren’t. But I still think there is something gross about it.

RB: Who do you think is responsible in the food chain of literature? If an editor receives a very hostile review, why is the editor obliged to publish it?

MA: He’s commissioned you, and that’s the way it goes. But you would probably stop using someone if they were always like that. If it looked off—why is the reviewer enjoying saying this? Some people enjoy being insulting.

RB: (Laughs)

MA: I got over it when I was about 27 or 28. I stopped enjoying it. But some people go on all their lives, and they are getting quite elderly and they are still insulting everyone. It’s a sign that something isn’t right in your own life.

RB: As long as I am covering the waterfront—you observed about your friendship with Christopher Hitchens [whom Lionel Asbo is dedicated to] that he was your closest friend because you could confess anything to him. Did that go both ways?

MA: Yeah.

RB: Is that a unique quality?

MA: I don’t think it happens very much. It was what my father always used to say to Philip Larkin, and says it in the letters quite often: “Nothing is too disgraceful that I can’t confess.” Not a deed, often, just a thought.

RB: Like you were thinking about killing kittens.

MA: Yeah, something like that. Hitch was like that. Because with everyone else, everyone else has susceptibilities. Everyone else, it seems to me, has for some reason or other to do with their lives, thoughts—some things you just couldn’t say to certain friends. They would think you very gross. To take an example, Hitch and I could make racist jokes to each other, and the butts of these jokes were never the people of other races, but the people who liked saying that kind of thing. So the joke was always on the teller. But we had great fun with that. I couldn’t imagine having that kind of conversation with anyone else.

RB: What will Hitchens’s standing be in five years?

MA: I think he will be regarded as one of the great essayists of his time. And it’s not an art with a huge constituency. And yet he got a huge constituency. He repopularized the form.

RB: Being a ubiquitous guest on cable TV helped.

MA: Yeah, he was so incredibly telegenic, and the voice—

RB: And the shirt buttoned to allow the visibility of some manly chest hair.

MA: And the sort of air of danger that he might say something—in his life, in the positions that he took, there will always be a bit of controversy about that.

RB: He is still not forgiven for what some thought was a betrayal of Sid Blumenthal (a Clinton apparatchik). There was small instance that bothered me. He got into a dispute with Studs Terkel and then wrote that not only had Studs served some awful white wine but that he was stingy in pouring it.

MA: A low blow.

RB: I thought that was small.

MA: Any port in the storm. You see, that sort of abrasiveness combined with on the whole beautiful manners—

RB: He could go off at any time.

MA: Yeah, and if a taxi driver gave him any lip, whoa. He wasn’t P.C. about it. Or a waiter, Jesus. I would never do that. He would take anything, it wouldn’t matter from which direction, up or down.

RB: Your biography [Martin Amis: The Biography, by Richard Bradford] is being published here in the U.S. shortly.

MA: It’s coming out here?

RB: (Laughs)

MA: As well as egotism there is vanity. Vanity got me in to that.

RB: Geoff Dyer reviewed it and claimed that biggest problem with it was that it was so poorly written.

MA: My beef with it was that he [Bradford] made up all these quotes, and gave me the sort of genteel grammatical habits that he has. “He said to myself,” that sort of thing. “As regards myself”—I don’t talk like that. And the sort of illiteracies, like using “infamous” when what they really mean is “notorious,” I more or less got him to take out that. But when he got to talking in his own voice, he said, “‘Yes,’ Martin muses,” and then he talks in my voice. (both laugh)

RB: Well, thank you.

MA: Thanks Robert, nice to see you again.