My Letter From Oliver Sacks

Migraines, 3D magic, and an unlikely correspondence from one “incredibly stereoscopic person” to another.

Neurologist Oliver Sacks has written a dozen books about the strange things that happen when people’s brains don’t work quite as they’re supposed to. His case studies have been adapted into feature films, documentaries, and even a ballet and an opera. He is a frequent voice in science programming on television and radio. Ever since his book Awakenings was adapted as a major motion picture in 1990, Dr. Sacks has remained an influence in culture and popular science.

While Dr. Sacks’s most well-known books are compilations of medical case studies, he also wrote autobiographical books about the disorders that afflict him personally, and two memoirs, including the recently released On the Move about his early years in 1960s America after growing up in England. But there’s one thing he wrote that means more to me than any of those, and until now nobody but me has ever read it. In November 2002, Oliver Sacks wrote me a letter.

Dr. Sacks did not write to me out of the blue. It was a reply to a letter I had written him. I had a specific question about neurology and vision and I couldn’t find the answer myself. I realized that if anyone knew the answer, he would. So I asked and he answered.

In 1952, while Oliver Sacks was in England studying medicine at Oxford, the first 3D feature film was released in America: a jungle adventure called Bwana Devil. The New York Times called the movie “puerile” and “crude” but audiences loved it, launching a first wave of 3D films. Unfortunately, the technology of the time left audiences with headaches, and 3D movies quickly faded from mainstream into a long period of novelty.

I grew up in the 1980s, when 3D movies were uncommon, but not forgotten. Occasionally a movie like Jaws 3-D came out, and I was amazed. When I saw a diving mask sinking underwater just inches in front of my face, I felt like I could reach out and grab it (forgetting that moments earlier it was worn by a character who was just eaten by a great white shark). If the technology existed to make a movie that immersive, I couldn’t understand why every film wasn’t made in 3D. The mere fact that 3D cinema was possible excited me.

I have always been an “intensely stereoscopic person,” a phrase I borrow from Oliver Sacks, who described himself the same way. The fact that human brains (and those of many other mammals) can take two slightly different flat images — one delivered from each eye — and turn them into a multi-layered world rich with textures and depth and space between objects absolutely amazes me. There are times when I literally pause to look around me and marvel at this.

Growing up, I loved 3D photos and illustrations, and eventually made my own. I studied comic book art converted to 3D by Ray Zone, and in high school I drew anaglyph 3D images by hand using red and blue colored pencils.

In college, I went through a period where I rented every Alfred Hitchcock movie I could find at my local video store. But I deliberately avoided Dial M For Murder after learning that Hitchcock intended it to be viewed in 3D. When it was originally released in theaters, the 3D fad had passed, and only a 2D version was shown, so audiences never saw the movie Hitchcock really wanted them to see. I finally got my chance to when a restored 3D version was screened at New York City’s Film Forum in December 2001.

It was great.

I longed for a 3D movie renaissance long before Hollywood revived the fad in the mid-aughts. I bought antique 3D cameras. I collected 3D glasses. And I spent a lot of time playing computer games wearing LCD shutter glasses that turned almost any modern game into a 3D experience, positive that this was the future of gaming. It’s with relief that I see modern virtual-reality systems like the Oculus Rift and Google Cardboard finally bringing 3D games closer to mainstream.

I know there are other people like me who are actively interested in how we perceive depth (and other related topics like how we perceive color, or how vision works at all) but I don’t know how common it is. In my profession, photography, I think every day about how a lens, sensor, and light all work together to record images in a similar way that an eye does. I’ve considered that my interest in photography fuels my interest in stereoscopy, but my interest in 3D vision predates my understanding of how cameras work. Even as young as five years old I recall slightly crossing my eyes to create convergences in repeating patterns (pegboard, chain-link fencing etc.) and watching how some areas appeared to float on a different plane as my eyes focused at different depths. I didn’t understand the mechanics of 3D vision, but I intuited what was happening. A decade later, when I saw my first “Magic Eye” poster, I grokked immediately that it was a variation of the “pegboard effect” I observed as a child. Clearly other people were as interested as I was in stereoscopy, even if it wasn’t a topic of conversation among my friends.

In the fall of 2000, I discovered the New York Stereoscopic Society, which held quarterly meetings at the American Museum of Natural History. Typical meetings involved a presentation of a large 3D photo or film, followed by members informally showing off their own 3D projects. I joined the NYSS and spent a couple hours every few months with my fellow 3D enthusiasts.

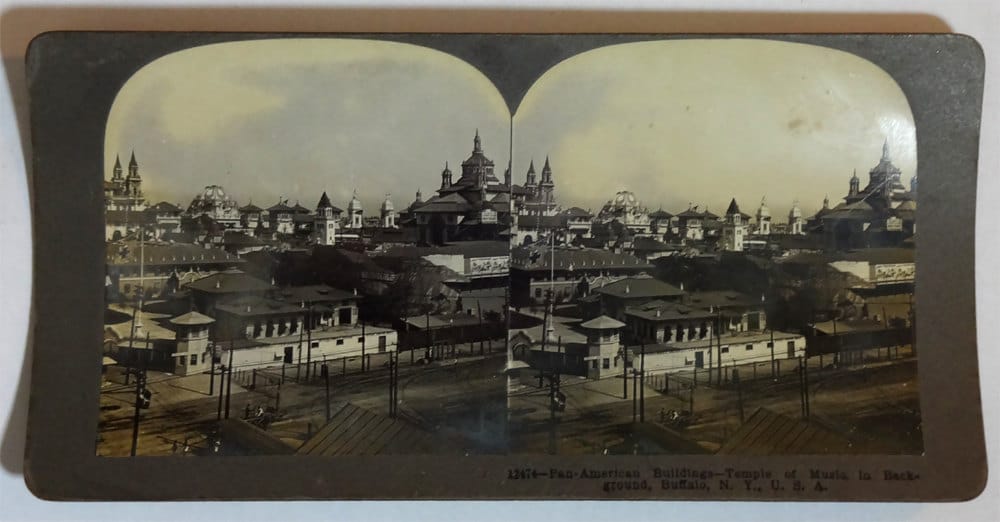

At a meeting in October 2002, a NYSS member named Paul Pasquarello presented a 3D slide show commemorating the centennial of the 1901 Pan-American Expo, a World’s Fair held in Buffalo, New York. Attendees of that World’s Fair were able to purchase souvenir “stereo cards” featuring two photos taken from slightly different vantage points printed side by side. Viewing a stereo card through a stereoscope (a bit like a primitive View-Master) let you see only one photo with each eye, causing your brain to interpret the resulting composite as a 3D image. For the Fair’s centennial celebration, a group of historians at the Buffalo Historical Society managed to collect more than 100 original stereo cards, restored them, and created a slide presentation to tell the World’s Fair’s story in 3D.

Paul Pasquarello presented these slides synchronized to a narrated audio track explaining how Buffalo was chosen for the Expo and why it was historically significant, being the first time most attendees saw electric lighting.

To project the images in 3D at the meeting, a pair of slide projectors were set up side by side, synchronized so that one would project the right-eye image and the other would project the left-eye image. The audience was given polarized glasses that allowed each eye to see just one image.

Normally a slide projector blacks out briefly between slides as it advances to the next image. But to make this presentation a little fancier, there were actually two pairs of projectors set up, allowing for a smooth fade transition between photos. One pair of slide projectors would fade out and advance to the next image after the other pair of projectors finished fading in.

This is where the trouble started.

One pair of slide projectors was accidentally set up in reverse. The projector that should have been projecting the image meant for the right eye was instead projecting the image intended for the left eye, and vice versa. This had an unnatural effect. The background appeared closer than the foreground. Where objects overlapped, they appeared broken. Things that should have been convex were instead concave. Faces and buildings seemed inside out.

The easy fix for this would have been to simply turn around my 3D glasses. Then each eye would get the correct image so that everything appears natural once again. Since the glasses were the common cardboard variety, I could have simply folded the earpieces backwards and worn them comfortably.

But this presentation used two pairs of slide projectors that alternated, and only one of them was set up incorrectly. So I would have needed to flip my glasses around and then back again for every other image to view them all correctly. I did this at first, but it quickly became annoying.

Paul could have stopped the presentation to correct the situation, but the slides were synchronized to an audio track. Rather than deal with the complications of resetting it all, he let the show continue, apologizing for the visual discomfort.

I couldn’t watch. The situation hurt my head, so I just closed my eyes and listened to the audio track tell the history of the 1901 World’s Fair.

But my mind wandered. I began thinking about how malleable the human brain is. When presented with confusing input, it can often self-correct. I recalled an experiment where a test subject wore special glasses that flipped his view upside-down. At first, he had trouble walking, and could hardly write his own name. But after a week, his brain made sense of what it was seeing. He learned to ride a bike again. His brain adjusted.

But is the brain malleable enough to adjust from the situation I encountered? If signals crossed in such a way that the brain mistook the right eye’s image for the left and vice versa, would it eventually make sense of it? If a person were born this way, would their brain correct itself, or would they simply live with this reverse-z-axis view, not knowing that they perceived the world any differently than anyone else?

I wondered if anyone had actually done the experiment, spending a week wearing glasses that reversed their view and reported what happened.

So I researched the topic as well as I could on Google. Without knowing a word to describe this effect, I was at a bit of a loss for how to search. Finally I found a term that described what I experienced—pseudoscopic vision — but the results using that term were unrelated to the intent of my query. There are plenty of relevant results for “pseudoscopy” today, but in 2002 they were mostly about incorrectly made holograms and such. I could not find an answer to whether anyone had conducted this experiment.

Since Google failed me, I wished that I knew an expert I could ask. And that’s when I thought of Oliver Sacks.

Before 1996, I was vaguely aware of Dr. Sacks, but I never read any of his books until the summer of that year when I took a road trip up the West Coast, staying at youth hostels along the way. In Ashland, Oregon, I stayed at a hostel that had a copy of The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat in the common room. I picked it up out of curiosity, and became so absorbed that I spent my first day in Ashland finishing the book.

The book describes 24 neurological case studies. There was the man who couldn’t form new memories and believed it was still 1945. There was the woman who lost the sense of knowing where her limbs were without looking at them (the way you can close your eyes and still know if you hold your arms out to the side, for example). And there was, of course, the man who was unable to recognize simple objects or people, mistaking at one point his wife for his hat.

I loved it. It was science writing I could understand. It wasn’t too technical, didn’t require a deep understanding of neurology, but it still educated. It told amazing stories that could happen to anyone (although they were too frightful to imagine happening to a loved one), and described the magnificent things that our brains can do when they aren’t working correctly.

I sought out more of his books. His 1970 book Migraine, about migraine headaches, was more technical than The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat, and I found it a difficult read. Being his first book, I assumed he wrote it before he perfected his method of science storytelling for the layperson. His use of medical terms without definitions suggested it was meant for an audience of fellow scientists and doctors. Although it was interesting, I never finished it. Here is a representative passage from a section titled “Vasomotor Theories of Migraine.”

Wolff was able to show, in a variety of elegant ways, that the intensity of migraine headache is closely proportional to the dilation of extracranial arteries, and could be diminished by the effects of manual compression, adrenaline, and ergotamine on the dilated arteries, or by centrifugation of the entire body. In the later stages of migraine headache, it was shown, dilatation of the offending artery or arteries might be followed by a train of local changes, with exudation of a polypeptide-rich fluid provocative of local pain, and finally, a sterile inflammatory reaction.

I sort of understood that. But it wasn’t quite as easy reading as the case studies of his other books. However, as a migraine sufferer myself, I frequently revisited the book, hoping it would get easier to read as I got older.

As migraines go, I’m pretty lucky. My migraines are short-lived, ending in a few hours, unlike some people whose migraines debilitate them for days. But I am fascinated by a symptom I share with other sufferers of what are known as “classic” migraines: a type of hallucination scientists call “auras.”

Although the text of Sacks’s book caused me trouble, the included images of migraine auras illustrated by different migraine sufferers inspired me to illustrate my own visual aura, which I posted online in 2009 with this description of my typical migraine:

For me, an aura usually starts out as a tiny shimmering spot in the center of my vision. It looks a bit like the after-image you see when someone takes a flash photo of you. But instead of fading like the after-image from a flash would, the spot slowly grows. As it gets bigger, I can see that it has details: it is a colorful shimmering crescent wrapped around a white circle. Gradually, over the course of 20 minutes or so, it grows until the white center fills my entire field of vision. I’m temporarily blind. And then, over the next few minutes it slowly fades away until my vision is back to normal.

Seventy-five comments were left on that post from people describing their own migraines. I felt a kinship with people who had similar experiences and left notes like, “As one sufferer to another, I’d just like to say that your description of your migraines is exactly—down to the detail of the shape of the aura’s growth—the same kind of migraine I get.”

My post was hardly a case study, just a description of a singular event by a layperson who enjoys reading real science writing. But I wouldn’t have written it at all if not for Dr. Sacks’s books which I enjoyed so much.

I also enjoyed his occasional articles in the New Yorker magazine. In fact, just one month before that fateful NYSS event, I read Dr. Sacks’ most recent New Yorker piece about a patient who could not read words, although she had no trouble reading individual letters and could even write just fine. That article began with this sentence: “In January of 1999, I received the following letter, from a woman I will call Anna H.”

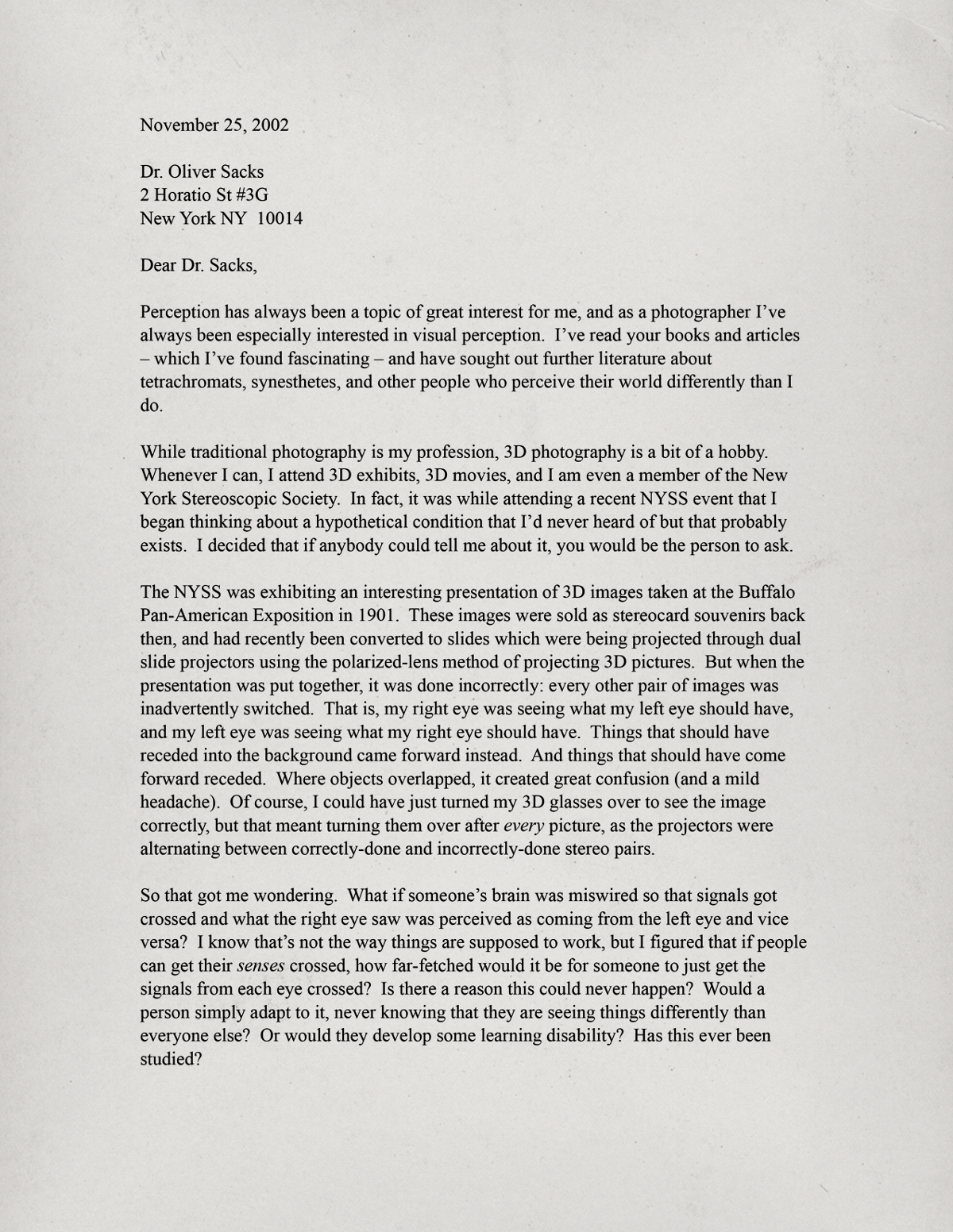

A month later, as I pondered how I would possibly get in touch with Dr. Sacks to ask him about pseudoscopic vision, I remembered that sentence. “In January of 1999, I received the following letter…” Ah-ha! He reads his mail! It seemed like a long shot that I would hear back from him, but I decided to write him a letter.

I searched his website for an email address. His contact page said, “Dr. Sacks does not use computers—he prefers mail or fax.” So I typed up a letter and sent it in the mail.

I dropped it in the mail and tried not to think about it much so I wouldn’t be disappointed if no response came.

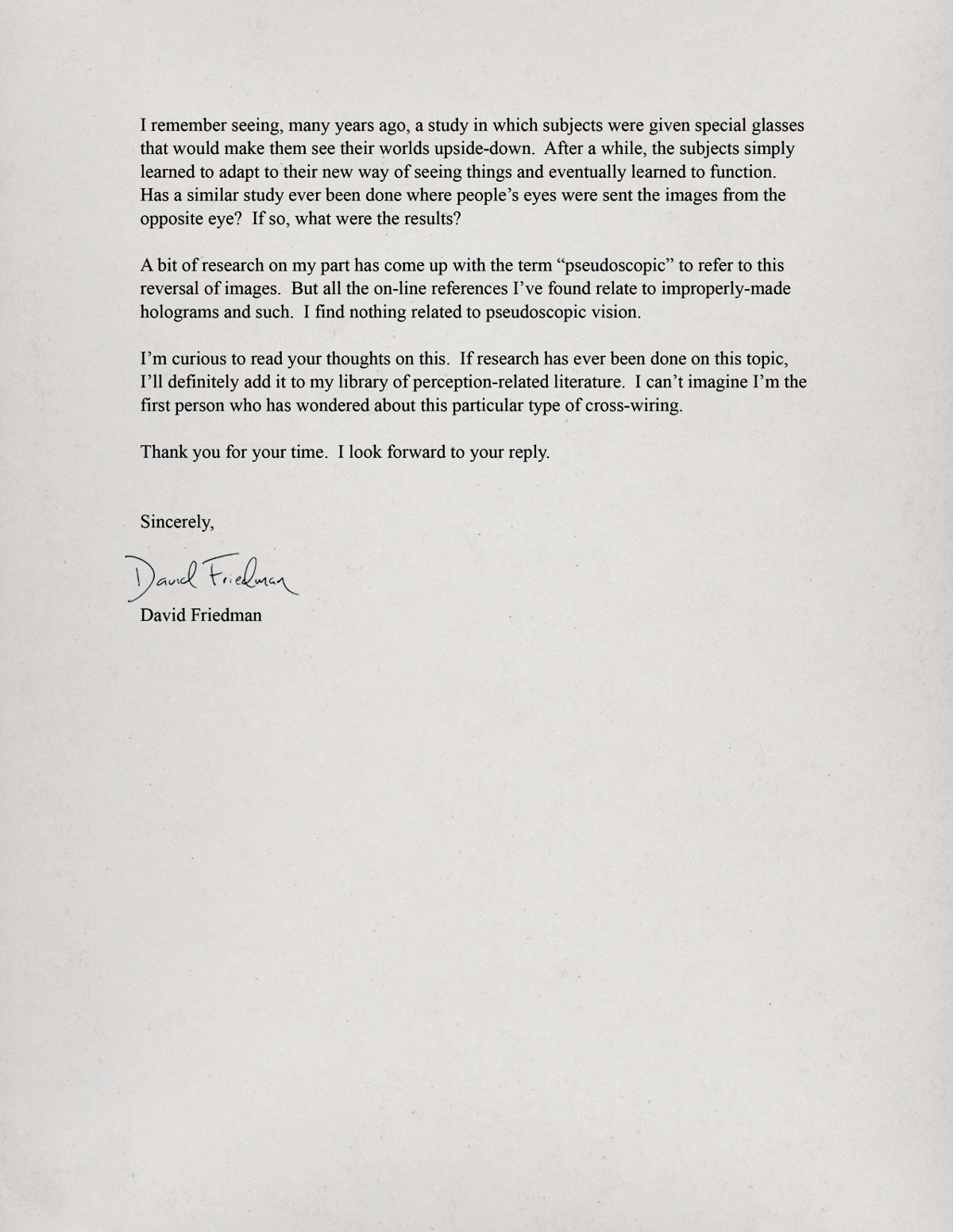

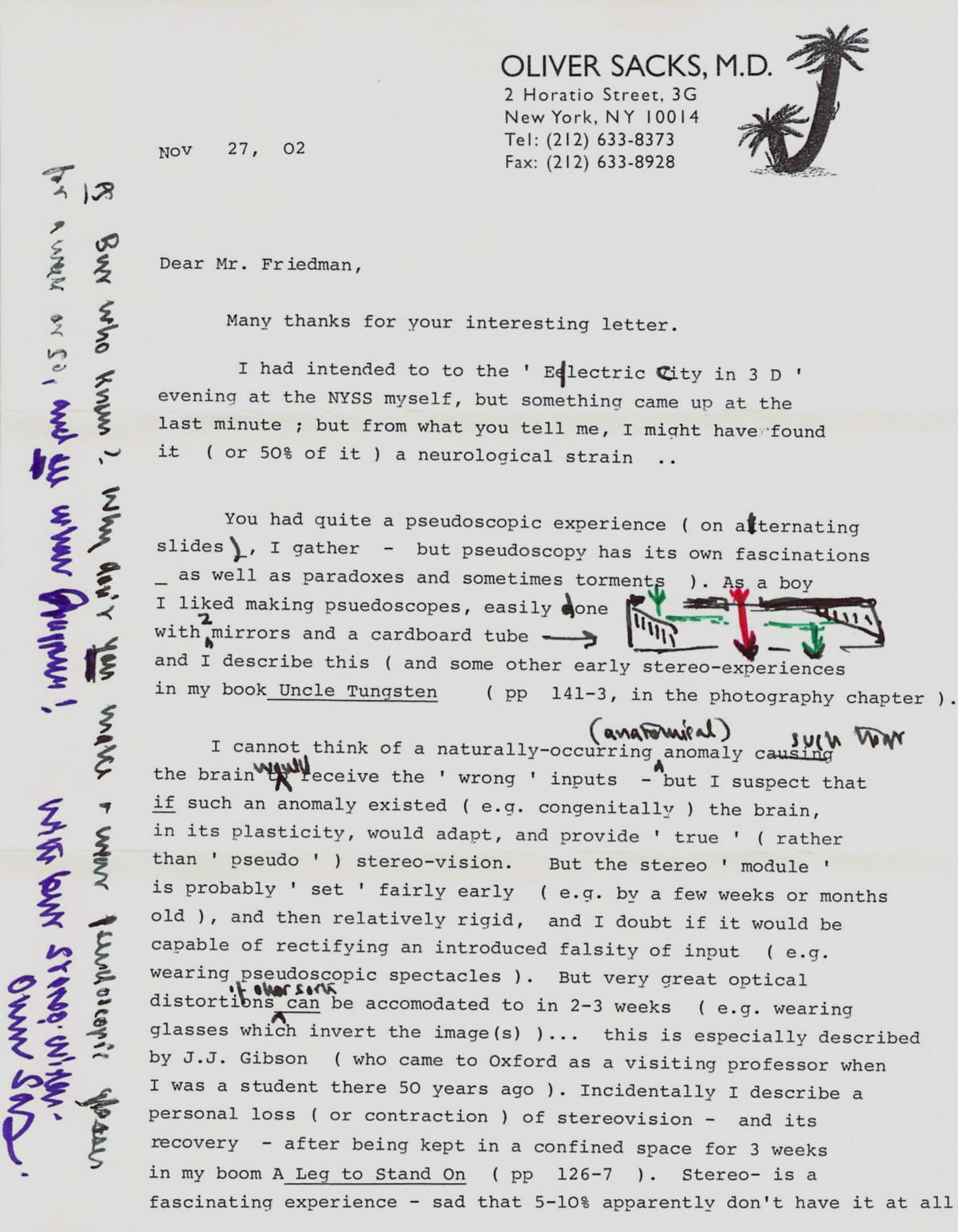

Less than a week later, I got this letter in the mail from Oliver Sacks:

So many things rapidly went through my mind: It was typed! On an actual typewriter! And when he ran out of space, instead of continuing on a second page, he finished the letter by hand! And he drew a diagram! And he planned to attend the same event I went to! I could have met Oliver Sacks! Wait a minute, what if I already have met Oliver Sacks? What if he was at one of the previous events and I didn’t even know who I was talking to? Or what if he was there and I didn’t meet him? There are a lot of old bearded men at these things. Which one was he? And how embarrassed should I be that he says he addresses this very question in his new book Uncle Tungsten which I’ve already bought but haven’t read and now it’s obvious that I didn’t read his book even though I claimed to be a fan and now he’ll never believe that I really am a big fan of his. And on top of all that, he actually gave a pretty good answer to the question.

But perhaps my favorite part was the note at the end. It’s hand-written and sideways, so maybe you can’t read it. But it says:

P.S. But who knows? Why don’t you make and wear pseudoscopic glasses for a week or so, and see what happens!

He ended by urging me to do a hands-on experiment. He’s encouraging me to be a scientist. Well, why not? Anyone can do science. It’s not just for academics and professionals. But not for a second had I even considered doing the experiment myself. I only looked for the answer elsewhere.

I put down the letter and grabbed my copy of Uncle Tungsten. I skipped straight to the chapter on photography so I could read about his childhood experience making a pseudoscope. I felt like I was cheating reading the book out of order instead of as the author intended, but he had given me an actual page number so I figured I had his permission. Here is his observation on using the pseudoscope he built as a young man, as he wrote in Uncle Tungsten:

It was also intriguing to reverse the pictures. One could easily do this… by making a pseudoscope, with a short cardboard tube and mirrors, so that the apparent position of the eyes was reversed. This caused distant objects to look closer than nearby ones—a face, for instance, might look like a concave mask. But it produced an interesting rivalry or contradiction, for one’s knowledge, and every other visual cue, might be saying one thing, and the pseudoscopic images saying another, and one would see first one thing then another, as the brain alternated between different perceptual hypotheses.

I wish I could tell you that I went on to actually build a pseudoscope and conduct the week-long immersion experiment myself, but I did not. Over the years I’ve seen detailed plans for building pseudoscopes online, and a few pseudoscopes have become commercially available (and then unavailable), but I never had a week to spare viewing the world pseudoscopically. But I do think about his suggestion often. Now that I have two little boys, I look forward to echoing the sentiment when they get old enough to ask questions of a scientific nature. “Why don’t you do an experiment, and see what happens!”

In 2006, Dr. Sacks wrote a piece for the New Yorker about Sue Barry, whom he nicknamed Stereo Sue. Sue was born cross-eyed, which was corrected through surgery, but she did not have stereo vision. Her eyes worked, but she was only able to see flat two-dimensional images from each eye separately. She had never developed the ability to merge them into a 3D image.

Eventually, through vision therapy in her forties, Sue finally gained the ability to perceive depth the way most people do.

The article included excerpts from her diary describing her newly gained 3D vision. They really resonated with me, as she describes the same kind of delight I find when I pause to look around and appreciate stereoscopy.

February 22: I noticed the edge of the open door to my office seemed to stick out toward me. Now, I always knew that the door was sticking out toward me when it was open because of the shape of the door, perspective and other monocular cues, but I had never seen it in depth. It made me do a double take and look at it with one eye and then the other in order to convince myself that it looked different. It was definitely out there. When I was eating lunch, I looked down at my fork over the bowl of rice and the fork was poised in the air in front of the bowl. There was space between the fork and the bowl. I had never seen that before…. I kept looking at a grape poised at the edge of my fork. I could see it in depth.

Three years later, I attended an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called The Mind’s Eye that was part of the 2008 World Science Festival. Oliver Sacks was interviewed by journalist Robert Krulwich. A large part of the conversation centered on stereoscopic vision.

Sue Barry, it turned out, was in attendance. Dr. Sacks told the audience her incredible story. But he also revealed something else: Dr. Sacks had lost his vision permanently in one eye due to a rare form of cancer.

He told the audience that he was very sad to have lost stereoscopic vision. As he explained to us, “I have always been an incredibly stereoscopic person.” When I heard that sentence, I knew immediately what he meant. And because I shared the feeling about myself, I felt great sympathy and sadness. It mirrored equally the joy I felt for Sue Barry when I read about her gain of stereoscopic vision.

Now Dr. Sacks’s cancer has spread from his eyes to his liver. In February of this year, he wrote an op-ed in the New York Times announcing that he only has months to live.

I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

I’m pretty sure I never met the man. Still I’m saddened by the news and I already miss him. In the op-ed he mentioned that he has several books nearly finished. I assume they will still be published, and I have no doubt Dr. Sacks will continue to influence and inspire. Meanwhile I have a letter to hold on to and a lesson to share with my sons when they become old enough to express inquisitiveness in science. And when they ask why I wrote to Oliver Sacks, I will give them his books so they can see the depth of his work for themselves.