My Sporting Life

From the very first moment we suit up for gym, our physical abilities can influence who we become or reveal who we were meant to be: blooming star athlete or total band nerd.

1969, Atlanta, Ga.

My teacher sends me home from kindergarten with a note to my parents. The note says that, unlike the other children in my class, all of whom are proceeding at the expected pace of social development, I seem to be having problems adjusting. This, apparently, is most notably demonstrated in my complete inability to skip, which my parents are instructed to correct with all possible expediency. My mother puts me through an aggressive skipping tutorial in our living room, while my father watches in horror. This is followed by many hours of exhausting skipping practice, and soon I am a master and am allowed to pass on to the first grade. My father never recovers from this humiliation, and a negative tone settles into our relationship that will last for the next 35 years.

1970, Atlanta, Ga.

My two brothers and I receive bicycles for Christmas. My father takes us to the local elementary school parking lot so we can learn to ride. We quickly pick up the basics, although we bump into each other a lot and there are several little crashes. The one thing we do not learn, however, is how to brake. This little essential takes on new urgency when we ride home and I find myself coming down a hill toward a major red light, without the slightest idea of how to stop. As my high-pitched screams pierce the quiet of our suburban neighborhood, I have no recourse but to steer left, jump the curb, and slam my bike into a foot-high stone wall that surrounds a local park. I fly over the handlebars, roll down an embankment, and come to rest at the feet of some Frisbee-throwing hippies, who look down at me, stoned and dumbfounded. My ultra-conservative father is humiliated—again.

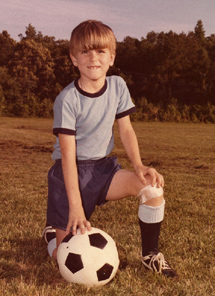

1972, Atlanta, Ga.

I join a youth soccer team, the Cosmos. I remember this experience fondly, and even into adulthood I consider it as the finest display of physical acumen I will ever muster. In my memory, I am an eight-year-old soccer machine, slashing across the field and skillfully eluding defenders as I bicycle-kick the ball into the upper corner of the net to win the game. Years later, my mom describes the experience this way: “I always loved watching you play soccer. You were so cute. You never cared where the ball was, you only wanted to run up and down the field. You’d run as fast as you could one way, then turn and run as fast as you could the other way. It was a total scream.”

As she tells me this, she balls her fists close together and makes little pumping motions with them, to simulate my cute little legs pumping aimlessly up and down the field.

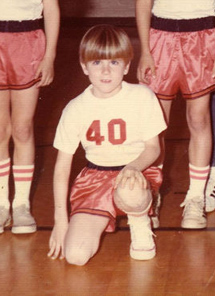

1972, Atlanta, Ga.

I follow my soccer success with a stint in youth football. In the first of many pairings that will demoralize me through the years, I am assigned to the same team as my older brother Larry. I have only two memories of this experience. The first is of diving into the pile after already-completed tackles, just so the announcer would have to give me credit for participating in the play. “Smith takes the ball and sweeps left for five yards, and is taken down by Cooper, Agee, and Cassels!” I am totally about unearned glory, because it is the only glory at my disposal. Not so with Larry, my athletic doppelgänger. Riding home after a game, I am in the back seat, and call up front, “How’d I do, Dad?” He replies, “You did fine, son. You really gave a hundred percent out there.” Larry, unable to resist, then asks how he did. The response: “You were fantastic, Larry! You gave a hundred and ten percent!” They then go into a bizarre Abbott-and-Costello-type recounting of a key fake fumble in the game. (“Who got de ball?” “You got de ball?” “I don’t got de ball.” “He got de ball.” “Who got de ball?”) I lie down in the back seat and mourn the ten percent of extra effort I didn’t bring to the game.

1973, Atlanta, Ga.

I join a community youth basketball team. One afternoon before practice, I am on a side court with a friend shooting baskets while my coach plays in an adult pickup game on the main court. Our ball gets away from us, and I cut across the main court to chase it down. My next memory is of an out-of-body experience, watching myself stagger down the street a couple of blocks from my home, leaning against parked cars for support. When I get home, I am completely out of it, and my parents panic. Fortunately, my coach is able to fill in the blanks for them. As it happens, in my zest for getting my ball back, I got caught up in the traffic of the adult game. My coach ran me over, knocking me out cold. I was then picked up and placed on the bleachers so they could continue their game, and, at some point, according to my coach, I “just disappeared.”

1975, Atlanta, Ga.

I enter Little League baseball on a team called the Mets. One of the assistant coaches for the team is, coincidentally, the same coach who ran me over on the basketball court. Our team goes on to win the league championship, though my contribution is limited to screaming, “We want a pitcher, not a belly itcher!” from the safety of our dugout. After several games are appended by my heartbroken sobs over not getting to play, my mother forces my father to confront the coach and insist that I be allowed on the field. My father is ignored, and humiliated.

1976, Atlanta, Ga.

In middle school, we are forced to play dodge ball, the goal of which is to take out all the members of the opposing team by heaving balls at them from close range. If you hit them, they are out. If they catch what you throw, you are out. I soon settle into the role of “last one picked” and first one knocked out, and I spend the rest of the game sitting in the bleachers, conjuring fantastic stories of a world where dodge ball is the premier sport, and I am its most famous star. Later in life, I will be dismayed to see my stories co-opted by Ben Stiller.

Also, there is a kid in my gym class with a two-inch “outie” bellybutton you could hang a jacket on.

I soon join the school band.

1978, Atlanta, Ga.

At the outset of freshman year, I quickly learn that the terrors of middle school gym were nothing compared to what awaits me in high school. I soon establish a reputation for being the only one in class to fail every single aspect of the Presidential Physical Fitness tests. In a game of “marine football,” which is like regular football but without as many rules, I somehow manage to piss off the star of the varsity football team and turn around just in time to see him coming at me with a velocity I couldn’t believe possible. He hits me square in the chest and I am sent airborne in a beautiful, flailing arc. When I crash back to earth, flat on my back, I am completely disoriented. It takes me a few minutes to find my shoes, which had remained on the ground when my body took flight.

Eventually, I will stop dressing out for gym and my coach will pass me anyway, as long as I promise to spend PE hanging out in the band room.

1979, Umatilla, Fla.

My parents divorce, and my younger brother and I move with my mother to a tiny country town. My brother Larry stays with my father in Atlanta. This is good for me because it gives me the opportunity to be the cool one for a change, and—free from his shadow—I in fact blossom for a brief while. Unfortunately, Larry develops some problems with truancy in Atlanta and is sent to live with us, and so I am no longer the cool one. I decide to try to regain my mantle of cool and emulate Larry by joining the track team, of which he is once again the star. And in a further attempt to raise the bar even higher for myself, I compete head to head with Larry in his events—the mile and two-mile races. Over the course of the season, I come in last place in every single race but one. (In that race, I get my legs entangled with another runner at the beginning, and he falls down. My second-from-last finish is my biggest victory.)

But losing in and of itself is not sufficiently demoralizing: According to the rules of track, a runner must drop out if he gets lapped. This happens to me in every single race, and it is always Larry who does the honor of forcing me out. I stumble onto the infield grass and shout encouragement to him as he cruises on to glory.

Larry also turns out to be better at band than me, and somehow he even avoids the “band fag” moniker. By now it is obvious: He is beautiful, talented Marcia and I am square, four-eyed Jan.

1980, Umatilla, Fla.

The high school holds an all-night marathon basketball game for charity, and our marching band fields a team. At last, the opportunity to marry my passion for sports with my skill at band. We are assigned the coveted midnight to 8 a.m. spot. At some point in the game, I adopt a strategy of staying in one place, directly beneath our basket. Suddenly, every time our team gets the ball at the other end of the court, they just wing it to me, and I, being completely unguarded, throw it in for two points. I quickly begin racking up points. My status as a star is soon diminished, however, when my teammates tire of my getting all the points while they do all the work, and they begin bringing the ball upcourt themselves. In this environment, my edge—based as it is on a three-pronged strategy of no passing, no dribbling, and no pressure while shooting—is effectively neutralized, and I am a non-factor for the next six hours.

After graduating, Larry heads off to the Marines. My chance to rule the school, however, is usurped by my affiliation with the band, and I am forced to forfeit the opportunity to finally be cool. Years later I will make my peace with my brother, but I will not play sports with him.

1981, Umatilla, Fla.

My friend and I join the high school tennis team. I lose every single match except one. We create our own tennis uniforms, which consist of cut-offs, tie-dyed T-shirts, and bandannas—a look that would not have been out of place in early ’80s Castro Street. In the grand spirit of “Everyone-Gets-A-Trophy Day,” I am awarded a varsity letter just for trying. Our coach is my “Most Hated Teacher Ever,” and my one moment of tennis satisfaction comes when I drill her with the ball during a practice match.

1982, Umatilla, Fla.

In a moment of weakness that I to this day do not understand, I decide to make friends with Jesus Christ and his pals down at the local Baptist church. During a sports outing in which I, a freshly minted adult, am having a friendly game of softball with the church youth group, I run over one of the kids in my sprint to first base, knocking him flat (much as I was once knocked flat by my own coach). The kid is pulled off the ground, whereupon he shouts, “Jesus Christ, it’s just a fucking game!” This is possibly the most horrible thing I have done to this point in my life, and I am instantly filled with an overwhelming shame—a shame that I still carry with me. Mortified, I leave the field and turn my back on God forever.

1983, Umatilla, Fla.

In the midst of an incredibly turbulent time in my life I take up racquetball, which quickly becomes an outlet for my extreme rage. My style is one of rushing the ball, swinging at it wildly, and then slamming my racquet into the ground over and over while screaming “Motherfuck! Shit! Goddammit! Fuck! Fuck!” After going through four racquets in as many months, I give up the game for good.

1989, Tallahassee, Fla.

During college football season, I am watching a Florida State football game with some friends—a ritual that, in Tallahassee, borders on sacrament. At halftime, we head outside to toss a football around. At one point I leap in the air to catch a high-thrown ball, and a loud, tight fart blasts from my ass and echoes through the yard. Given that I am notorious for denying that I am subject to the same bodily embarrassments as other humans, this event sends my friends crashing to the ground in fits of laughter.

1992, Tallahassee, Fla.

Work friends gather in a local park for after-work games of co-ed volleyball. We play six-person teams and are all pretty much equals in terms of skill. I’m meeting new people, getting great exercise. It is seriously fun. But then the more we play, the more competitive some of the guys get. They want to play two-man volleyball, with “set plays” and lots of spiking. If you’re playing two-man volleyball, that means a lot of people are going to be sitting around waiting for their turn. And of course, winners get to keep playing, so the more aggressive players never get bumped off the court. The rest of us finally give up in disgust.

1993, Atlanta, Ga.

My wife and I visit Six Flags Over Georgia for a day of riding roller coasters. We have a wonderful time. That is, until I spot the first of many hoops booths, where you pay a couple of bucks for two basketball shots. If you sink both shots, you win a basketball. The park is filled with people dribbling basketballs, with some people dribbling two or even three balls. At the next booth we see, I hand over my money and take my first shot. Swish! I take my second shot. Clang! I try again. Same results—the first shot goes in, the second shot bounces off. “Motherfuck! Shit! Goddammit! Fuck! Fuck!” The afternoon quickly spirals out of control, and I buy more throws at every booth we pass. By the end of the day, we are exhausted, I have lost more than $30, and I still have no ball.

1998, Hilton Head, S.C.

On a business trip, I must play a round of golf with my boss and a coworker. This is the first time I have played golf since I had a set of kiddie clubs as a child. Somehow, I am selected to go first. I step up to the tee and swing. My foot, however, digs into the dirt on my downswing, and my knee briefly pulls from its socket. I drop to the ground, writhing in agony. My boss, a man of considerable sensitivity, calmly steps over my body, tees his ball up, and takes his shot. For the remainder of my time at the company I am called “Putts.”

2002, Lake Tahoe, Calif.

I go on vacation with a group of friends for a weekend of fun in the snow. Two of us join a beginner’s group class in snowboarding. Our instructor gives us pointers in the most basic moves, and we take turns trying them out. After a long time spent trying to get my feet into the clamps, and an equally long time attempting to stand up, I am on my feet and ready for my first attempt. I begin to slowly glide down a very slight incline and suddenly am executing a totally awesome 360-degree maneuver that leaves my classmates in awe. Our instructor sees the move for precisely what it is—a rank beginner whirling about in a spectacular manner. He tells me that when I get good, I’ll realize how difficult it is to complete that move on purpose.

For the rest of class I am unable to get my feet back in the clamps. While my classmates are performing smooth gliding turns and stops, I am lying in the snow, twisting my body into impossible positions, sweat pouring over my face as I try to get my boots to lock on the board. Eventually, I have so exhausted myself that I am nauseated. I give up.