Our French Connection

A two-week journey across the US—specifically towns named Paris, with a clipboard and a hundred questionnaires—to uncover what Americans think about the French.

There are cowboys with brown teeth and black hats in southeastern Idaho who tell you the French are just as good sons-of-bitches as you’re likely to find anywhere.

They mean this as a compliment. They’ve had four beers, you’ve had four beers, so you don’t hesitate to point out there’s actually common ground between today’s working cowboy and the Parisian. Each being rather, “I am who I am, fuck you very much.” It gets a big laugh.

“Hey Mike, d’you hear?”

“Hear what?”

“We’re French!”

“We’re French?”

“We’re high-falutin’!”

“Well, son of a bitch!”

A Gallup poll in February found that 75 percent of Americans now think favorably of France, up four points from 2011. Other signs of Francophilia percolate: A French movie won Best Picture for the first time at this year’s Academy Awards. Downtown Manhattan’s gone French—over the past few years, the Times says, “Parisians have infiltrated the highest reaches of New York night life.” Buzz surrounds a new parenting book, French Kids Eat Everything, which follows this winter’s Bringing Up Bébé: One American Mother Discovers the Wisdom of French Parenting—the author of which, a Paris-based American, was nominated as one of Time’s 100 most influential people in the world.

And yet, also this winter, Rick Santorum declared that if America were to emulate France, we’re headed for “the guillotine.” Mitt Romney chimed in, bashing President Obama for ostensibly seeking inspiration in European capitals, not American cities. And Newt Gingrich, in an ad called “The French Connection,” attacked Romney for speaking French “just like John Kerry”—harking back to the “freedom fries” period of 2003-04. The same era when, again according to Gallup, Americans were almost twice as likely to view France negatively as positively.

In America’s current political and media climate, the right hates France in particular, Europe as a whole, and the left stays mum, celebrating films and parenting techniques in lieu of the policies it admires.

Back in late December, I was staring out my office window, wondering, But what do real people think? Who the hell finds this kind of fluff damnatory? Was the Gingrich ad another piece of frivolous idiocy, or was it more? Personally I tend to like the French. Then again, I recently lived and worked in Paris, and just wrote a book about all the new ways I discovered to find the French aggravating and marvelous. So I’m probably not the best judge. But French and American affairs have been intertwined for centuries. Together we practically invented modern representative democracy—doesn’t that count for something? What do Americans really think about the French these days?

According to the United States Geological Survey, there are currently 25 populated places in the U.S. named Paris. In January, I chose four of them (plus one that didn’t show up in the survey), packed a carry-on bag, a clipboard, and a warm jacket, and headed out to learn what Americans currently think about the French—and whether or not it’s possible to buy a decent croissant in the heartland.

The road to South Paris, Maine, runs through Poland, followed by Norway—a feat not even attempted by Hitler. Then comes Oxford. Nearby are Naples, Mexico, Denmark, Sweden, Lisbon, Rome, and Wales.

The towns were so named for various reasons—for example, to honor a country’s newfound independence (Peru, 1821)—and partially because it was the fashion in the early 19th century to name freezing-cold, struggling communities after exotic-sounding foreign places.

To make China from South Paris is about 80 miles, depending on the weather.

During January in Maine, a lot depends on the weather.

When I land in Portland, the forecast calls for snow. My rental car, when I find it, smells like a new car as if christened by that one aunt of yours who keeps a bong next to the coffeemaker. Someone’s been high in the driver’s seat within the last couple hours—for a couple hours. Also, the emergency brake light blinks on and off randomly, even though the brake’s not engaged.

I think about complaining to get a discount, but the smell’s rather nice—sweet and piney. Just in case, I pull on my jacket and roll down the windows to ward off the good vibes, and set off for my dinner reservation at the only French restaurant in South Paris.

An hour later, I’m at my inn. It’s located up the road from a local French mime troupe—a theater started by an American mime who’d journeyed to France to learn from the great Marcel Marceau—but the company’s closed during winter; you can picture my sad face when I learn this news. Glenn and Janice, the warm, semi-retired owners of the inn, say there’s still plenty to see. They invite me in to their combination kitchen/dining/living room. It’s dark, surfaced with doilies and dolls. I explain why I’m visiting and Glenn says, “You know, Europe’s a liberal, liberal area. We’re not that liberal.” He chuckles. “I’ve been to Paris several times. So it’s not on the top of the list of places to revisit, if you know what I mean.”

“I’d go back in a minute,” Janice says, her face granite.

Glenn wants me to know why South Paris is notable—among other reasons, for giving the world Hannibal Hamlin, Abraham Lincoln’s vice president. “It’s funny,” he says a minute later, no longer chuckling, “we’ve had two other writers here before, two writers doing books about the Parises of America. Have you heard of them?”

“Do you remember their names?”

“I don’t.”

“Do you have any of their books?”

“None of them came out, far as I know.”

Outside, it’s sleeting. Gone is the sun. The streets are snow-covered, spackled with ice. It’s 4:30—time for an early meal if I want to beat the storm. “Just call Glenn if you get stuck, he’ll bring out the truck,” Janice shouts from the door. I inch the stoner mobile down the driveway and one steep hill after another. Across a river and into town, which takes me through a bewildering intersection where I get confused, lose traction, spin my tires, and a truck almost shish-kebabs me before I can catch some grit and move forward again.

The emergency brake light re-illuminates as I putter away to dinner.

Francophobia follows politics. In current America, Chirac’s opposition to the Iraq invasion led to public dumping of Bordeaux and the Congressional “freedom fries” order. Back in 1798, John Adams’s XYZ Affair caused a shift in public opinion, tacking from strongly pro-French to all-out scorn: “The tide is turned,” wrote Henrietta Liston, wife of a British ambassador to the U.S., “and now flows with violence against the French party.”

In 1968, the New York Times dispatched reporters to take the pulse of anti-French sentiment in the U.S. Supposedly, de Gaulle’s opposition to America’s presence in Vietnam had relit the Kill France fires. (De Gaulle’s public statements didn’t help; he told Time in ’67, “You have to be sure that the Americans will commit all the stupidities they can think of, plus some that are beyond imagination.”) Results on the ground were mixed: French restaurateurs in New York reported no loss of business; one Pittsburgh travel agent didn’t notice any anti-French sentiment, another placed an anti-France ad and reported an “overwhelming” anti-de Gaulle response. In Chicago, a restaurateur said he only sold French wine upon request. In Richmond, there were reports of travel boycotts, same for Kansas City and Detroit. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote in an op-ed, “We wish to emphasize that we do not hold the slightest feeling of ill will against Brigitte Bardot.”

Prior to World War II, most Americans had never met a European. Even the children of immigrants lacked a direct connection. According to Richard Pells’s history, Not Like Us: How Europeans Have Loved, Hated, and Transformed American Culture Since World War II, the idea of visiting Europe for any non-idle-rich Americans didn’t become feasible until jet airplanes started making transatlantic flights in 1958.

But the pendulum can swing positive, too. General Lafayette did celebrity laps of New England after contributing to the Revolutionary War. Once news arrived of France’s 1830 July Revolution, the “Marseillaise” was sung in theaters, and New Yorkers threw a two-and-a-half-mile parade. In fact, New York’s first ticker tape parade was held to celebrate the Statue of Liberty, a gift from France in 1886. Jacqueline Kennedy hired a French chef to run the White House kitchen in 1961, the same year that The Art of French Cooking was published and quickly sent to a second printing, followed by Julia Child’s debut on TV—and suddenly the nation felt compelled to make coq au vin for dinner guests. More recently, Midnight in Paris, Woody Allen’s latest film, has become his top-grossing ever.

Mark Twain’s travel book, The Innocents Abroad (1869) was the best selling of his lifetime. In it, he visits Europe and the Middle East. At that time, most Americans had little experience with foreign lands, let alone foreigners. People were curious—what was it like over there? Twain reports on his first dinner in Paris:

We went out to a restaurant, just after lamplighting, and ate a comfortable, satisfactory, lingering dinner. It was a pleasure to eat where everything was so tidy, the food so well cooked, the waiters so polite, and the coming and departing company so moustached, so frisky, so affable, so fearfully and wonderfully Frenchy!

At Maurice Restaurant Francais, the menu is Frenchy in the method of protein and cream, with added butter.

I come in from the freezing rain and a waitress seats me in a corner. I glance through the menu and order onion soup, chicken cordon bleu, and a glass of house cabernet.

The soup, when it arrives, is black and hot, and not bad.

The chicken, on the other hand, is a ship on a sea of triglycerides.

The wine, by glass two, is getting better all the time.

During the soup I ask the waitress if the chef is there. He is not, but she brings me a recent profile of him from the Lewiston Sun Journal. “There is less and less that is French, per the business environment,” Corey—the chef—says, regarding his menu. “I’ve even tried lighter fare, but people do not come here for that.”

The next morning, I go back to interview him, and Corey tells me he has “Americanized” the menu over time for current tastes. The heavy style of French food that was so popular when the restaurant started is simply hard to sell today. “People want new things.” We talk about the rise of international flavors, the many ethnicities present in today’s cuisine. He points out that the menu used to be written in French, but now it’s all English: “I didn’t want people to feel intimidated.

“Don’t get me wrong, I like the stuff,” he says, of his steaks and creams. “But from a health standpoint? I couldn’t eat it every day. And I love béarnaise sauce.”

Due to Maine’s proximity to Canada, several northern towns’ populations have French-speaking majorities. As of the 2000 Census, French was the fourth-most spoken language at home in the U.S. behind English, Spanish, and Chinese. And in two weeks, across the country, exactly four people will say to me, “Voulez-vous couchez avec moi ce soir,” though not once sincerely.

At night, trucks rankle through South Paris on their way elsewhere. At the Smilin’ Moose Tavern, I’m at the bar 15 minutes before my clipboard—loaded with questionnaires that I devised for the trip—becomes an object of room-wide interest. Soon everyone’s filling one out. I’m told repeatedly how the French are pretty big in Maine. Huge, in fact, particularly the language. Oh yeah, you’ll hear it in pockets, in Lewiston and Auburn, seeing how Maine has a high percentage of people who speak French at home. But of course that’s more to do with the proximity to Canada. Nope, living in Paris doesn’t lend any special affinity for the French. You get jokes about it, sure. But for the most part, France is a distant shore.

One woman introduces herself as the wife of the man who actually started Maurice Restaurant Francais, the original Maurice. “How about this for a strange fact,” she says. “My husband was born in Paris, France, and he died in Paris, Maine.”

I ask which Paris he preferred. She demurs, saying, “We had so many friends here, so many friends.”

And there’s an old turtle in plaid wool bunting, who’s been drinking since lunch. His face takes 10 seconds to catch up to his feelings—he laughs while displaying fear, or gets angry at me while smiling. He tells me he writes opinion pieces for the Sun Journal—very conservative—but: “I have nothing against the French. I wish I was French. I’d get more women than I do now!” he says, terrified.

I stumble onto a French drama on TV. Everyone’s dressed in black and gray. They move between coffee shops in a city of skinny homogeneity, characters taking their coffees to go—and that’s when I realize something’s off.

Back at the inn, I discover the TruTV channel (“We did dumb first. We do dumb best.”), then stumble onto a French drama. Everyone’s dressed in black and gray, wearing fleece jackets over cashmere like they’re going ice climbing after dinner. The women are confident, at ease. The men are duplicitous and envying of one another. Everyone has thick dark hair. They move between coffee shops in a city of skinny homogeneity, characters taking their coffees to go—and that’s when I realize something’s off. No French person has ever walked anywhere with a coffee. Plus I can’t follow the accent, and there are four times more Asians than I’ve ever seen on a French TV show (i.e., four)—and that is how I become conscious of the show being Canadian.

At breakfast, I’m joined by a small ancestor eating high-fiber cereal. Janice explains who he is, but I’m not listening because I can’t look away from his hair. Either he wears a hairpiece pulled down to his nose, or grows bangs from the middle of his forehead—like a baby owl flattened above the eyebrows. I ask him what he thinks about the French. No answer, but a smile. Glenn gets him talking about cars. I think of my own scalp, now thinning, and want to say, Teach me how to grow hair.

That morning’s Lewiston Sun Journal has an obituary for Allain M. DeHayes, 71, who died the previous day—of South Paris, Maine, born in Paris, France, 1940. On a sunny winter morning, South Paris is beautiful. Clouds are white, houses are white. The snow softens and powerful winds throw up huge, polygonal white gusts, like roofs being blown off houses. Leaving town, I drive to a Dunkin’ Donuts and buy a croissant that’s more roll than croissant, and more dish sponge than roll. In 19 hours, the most European thing I note during my visit is a deli sign advertising “Italians”—what in Maine they call hoagies.

Over the next two weeks, I ask 118 people to complete one of my surveys. Fifty-five people consent. They’re veterans, teachers, students, seniors, and children. A security guard, an abstract painter, and a gas station clerk. Several professors, multiple housewives, and a guy who owns his own jet. A journalist, a novelist, a mechanic. Two immigrants. A linguist. A physician, two surgeons, and a nurse. Receptionists, mid-level businesspeople, low-level businesspeople—and lots of people in service, hospitality, food, and manufacturing.

Altogether, I get nearly a 50/50 split on gender, and from all the colors of a racist’s rainbow, though I’m required to aggressively profile to achieve that last part.

The survey has eight questions ranging from general opinions to particular trivia. For example, “Whose side was France on during the American Revolutionary War?”

Sixty-six percent of respondents get it right: our side. Twenty percent are wrong. Incorrect answers include “the British,” “England,” “the opposite side,” and, oddly, “the French.” Other responses: “History was not my class in school—I hate it,” and “I am averse.” My favorite comes from a gas station attendant in Lexington, Ky., who writes: “I refuse to answer the rest of this survey. I love the French language. I have had many French friends.”

One guy in a parking lot outside a Dallas strip club says, “This has got to be a trick question.” And there’s another person, at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport, who will ask me, “You mean our American Revolutionary War?” Which appears to be a general concern—of the 55 people, at least 10 ask me to which American Revolution I am referring. Two people say, “But we didn’t have a revolution.”

Traveling around the country, introducing myself to strangers, I am not once rebuffed brusquely, by anyone. My rule becomes: If you loiter within 20 feet of me, I approach. And people are generous. They want to talk. Granted, I am not intimidating—I dress to blend in, and sometimes I shower; you might suppose I work for the bureaucratic wing of Greenpeace. But they seem to enjoy telling me what they think; they have lots of opinions to share about France, the French. The last place I’ve been where people were so open and forthright, in fact, was France.

There is a quote that has stuck with me from a 2007 interview I read with French President Nicolas Sarkozy; he said, “For my part, I think that the French and the United States are much more alike than they think. Much more. It is rare to find countries in the world that think their ideas are universal…. In the United States and France, we think our ideas are destined to illuminate the world.”

In every town I visit, it’s easier to find guns than books, and that’s true on the drive into Paris, Ky. But the Paris-Bourbon County Public Library is a squat, red bank of literature, and its collection includes two French dictionaries and an instruction manual called French: Step by Step by Charles Berlitz. It’s only been borrowed once, Dec. 5, 2001, despite promising to teach anyone “to speak correct, colloquial French as it is spoken today…without lengthy and involved explanations.”

The book says its method is conversational, of dialogues that “apply to everyday living” and “will not only hold your interest, but they will also stay in your memory.” I am chiefly intrigued by this point: “You will learn how to start conversations with people—how to tell a story—how people speak when they are excited—and you will even acquire the language of romance.”

Emphasis mine.

I find my way to a secluded table in the back of the library. In the book, three languages are displayed: French, English, and a version of French that’s meant to be read out loud as if you’re reading English. For example, if someone in the book says “Steak frites et sauce béarnaise,” it’s rendered as:

Steak frites et sauce béarnaise.

Steak and French fries with Bernaise sauce.

“Stake freet ay sewce bear-nayze.”

Sometimes this actually sounds semi-accurate out loud—I do so in a whisper, to avoid getting kicked out: “Par-dohn. Oo ay lo-tel ritz?” “La-ba, ah gohsh.” “Ess un bohn no-tel?” “Wee, muss-yuh. Tray bohn…ay tray shair.” But the majority of dialogues pertain to scenarios too bizarre to be of use to anyone. For example, the following conversation, from “At a Soirée (Evening Party),” could be a Wes Anderson movie casting session, but that’s about it:

PIERRE: What a pleasant gathering!

JEAN-PAUL: Yes, the guests are very interesting. Mrs. De Laramont has many friends, in very different circles. In that group over there by the window, there is a lawyer, a composer, a banker, an architect, a dentist and a movie star.

PIERRE: Well! I wonder what they are talking about, architecture, finance, music, law…who knows?

JEAN-PAUL: You can imagine! They surely talk about the movies.

PIERRE: Do you know who that very pretty brunette is, in an elegant black suit?

JEAN-PAUL: She is a star dancer from the opera. Her name is Yvonne Thomas.

PIERRE: And the two men who are talking with her?

JEAN-PAUL: The old gentleman is a conductor and the handsome young man is an actor, rather a bad one really.

PIERRE: Look! Do you see who is arriving now? It is Commander Marcel Bardet, the explorer of the bottom of the sea.

JEAN-PAUL: Well, do you know there is an article about him in today’s Figaro? What an adventurous life!

PIERRE: …and dangerous! You know, I know him well. He always tells about very interesting things. Let’s go and talk to him for a while. I’ll introduce him to you.

On the shelf is also Italian: Step by Step. In it, the same scenarios are repeated, word for word, though with subtle cultural modifications. Case in point: The French version of “At a Disco” has only one exclamation point; the Italian contains seven.

I’m walking out when I see that week’s New Yorker on a magazine stand, with the cover flap headline: “French Sex and Death: James Wood on Michel Houellebecq’s new novel.” In his review, Wood makes the latest book from probably France’s best-known living novelist sound quite undesirable to read. But he does not—disappointingly—fulfill the headline’s premise that sex and death in France are different from sex and death in other places—perhaps with fewer exclamation points? On another rack is Marie Claire. Its cover promises “The French Girl Diet—Eat Your Way Gorgeous.” Which turns out to be a truth well-stretched. The diet is called “Le Forking,” and its secret is that you are only allowed to eat what you can spear with a fork. Peas, not soup. But the rules are confusing. You can stab a chocolate pie, but you don’t get to swallow it. Perhaps the real benefit is to improve your hunting skills—Hunger Games for hungry girls.

I learn from Amazon.com that people who purchase French Women Don’t Get Fat also buy All You Need to Be Impossibly French: A Witty Investigation Into the Lives, Lusts, and Little Secrets of French Women by Helena Frith Powell; French Women Don’t Sleep Alone by Jamie Cat Callan; Entre Nous: A Woman’s Guide to Finding Her Inner French Girl by Debra Ollivier; and Chic & Slim Toujours: Aging Beautifully Like Those Chic French Women by Anne Barone. There is also a French Women Don’t Get Fat calendar—which does not, to my disappointment, contain swimsuit pictures.

Also available at the library is French Women Don’t Get Fat, by Mireille Guiliano, the New York Times no. 1 bestseller when it came out in 2004. That title is also a lie. French women get fat all the time, and they’re getting fatter. In Michael Steinberger’s Au Revoir to All That, he noted that by 2005, more than 40 percent of France was considered overweight or obese (compared to 64.5 percent of Americans). The same year, a European product manager for Weight Watchers told the International Herald-Tribune, “The market in France is growing and we believe it has an excellent future.”

Back when I worked in Paris, I’d tell female coworkers about this industry of American women buying books about the superiority of the amazing—and imaginary—French woman. Most of them would roll their eyes—because if you think American women and their publications hold French women to an impossible standard, French society is much worse. But there were also two girls in the office, arrogant to begin with—beautiful, skinny but curvy, their hair and comportment as though they’d just been stolen away from vigorous sex—who suggested with a silent shrug, “But of course.”

Paris, Ky., is located half an hour’s drive from Lexington. It is a town of approximately 9,000 people—many of whom, judging by appearances, know how to fork. It is the seat of Bourbon County, named for the Bourbons of France, and is itself named after the French capital to honor France’s contributions to the Revolutionary War.

A fact I offer without explanation: Eighty-three percent of people I survey in or near Paris, Ky., correctly answer the question about whose side France was on during the Revolutionary War—as compared to the 66-percent national average.

Nearby is Versailles, Ky., pronounced “Ver-sails.” On three occasions, I’m reminded to say it correctly or else the locals won’t understand what I’m talking about. But my focus is on Paris. The town, like its Maine sister, looks beat up: a classic American small town skidding downhill, emergency brake light blinking on and off. There’s a main street with offshoots featuring old, pretty homes, some trash-strewn alleys, a few churches, a creek with a home appliance in it, and lots of front yard furniture and cars on blocks; the surrounding hills and fields are used for horses and horse-breeding, and the land is beautifully pastoral. Several people tell me the town’s on the rise. This includes a coffee bean roaster. He started his business downtown because he couldn’t find a decent cup of coffee in Paris. “Come back in 24 months, it will be a completely different place. For the better.”

Down the street, at Lil’s Coffee Place, a lunch counter, my question on what’s good to eat is answered with “the quiche.”

“The quiche?” I say.

“We make three kinds daily.”

I think about it. “Well, when in Paris…”

“Right,” the woman says, and turns to warm it up.

Later, I ask the owner, Lil, who says she’s pro-French, if people there identify with France or French culture. “People who are new, I guess,” she says. “They’ll say they’re from Paris, like as if it’s France. But it’s Bourbon County that’s more important to older folks around here—the history of the area. History is long here.”

I talk to several shopkeepers and people on lunch break.

I walk around for an hour and count four wireframe Eiffel towers used for decorative purposes.

In a garage on Main Street, Riley’s Auto Body, two mechanics are hanging around the counter. The older wears a hooded University of Kentucky sweatshirt, the younger wears a blackened jumpsuit and a Kentucky beanie.

I walk around for an hour and count four wireframe Eiffel towers used for decorative purposes.

“What’s happening, man?” the older says to me.

“Well, it’s unusual.”

“Nothing we haven’t heard before.”

“I’m a writer doing a story about what Americans think about French people.”

“There you go.” He nods for me to continue.

“So I’m going around the country asking people, especially people in Paris—Paris, Kentucky; Paris, Maine—”

“Don’t forget Tennessee,” the younger one says, lighting a cigarette.

I explain about the questionnaire. The older one says, “Well, here’s your certified genius,” and gestures toward the other. “Yeah, I’ll do it,” the younger one says. “I got a 34 on my ACT.” His name is Tyler. Tyler’s got a wispy goatee and an eyelid droop. He smokes and keeps a running commentary going while he fills out his answers: “All right, one thing, they have good intentions, the French. But they don’t go about their foreign affairs correctly.” He grimaces, squints, and smiles. “They probably owed us at least one favor for World War II and Vietnam, back in 2003, when Chirac’s in the UN. Now, he should have backed us up, no questions asked.”

Tyler lights a new cigarette. The other guy, staring out the plate window, admonishes him, “Man, put that thing out in front of him.”

Tyler drops the cigarette. “Also, they should sweep up the dog shit off the sidewalk.”

“You heard that?” I say.

“Oh, I’ve been to Paris.” His tone suggests I’ve challenged him. Then he softens, caught up remembering: “I was like six when we went, I got a cousin over there, she married a French guy. What I remember is the streets were filthy, disgusting, then you look up and there’s the Eiffel Tower, so beautiful.” He rummages another cigarette. “It’s the contrast between those two—that’s France.”

Responding to the question, “Who is Nicolas Sarkozy,” 51 percent of respondents say correctly, “the president of France.”

One respondent, a wealthy businessman from Portland, Ore., gets into detail: “President of France. Has under 30-percent approval rating as of today.” He looks up and tells me, “If France would focus on the future more, I’d like it better. But they’re shackled to their past. They worship it. That’s what keeps France behind.”

Other responses to the question include “a writer,” “a politician of some kind,” “heard his name before but not sure,” and “Carla Bruni’s baby daddy.”

Americans are often surprised when I point out that Sarkozy is nicknamed “Sarkozy l’Américain” in France, that he loves Elvis and goes jogging. Living in Paris, I developed a thing for Sarkozy, his personality, not the politics—because he’s flashy, bombastic, short, despised, grandiose, and altogether nontraditional compared to the elite, stuffy competition. But even I was surprised, while doing research for this article, to learn that Sarkozy actually gave himself that nickname, l’Américain. Because it’s such a not-French thing to do—brashly self-inflating. In fact, it’s rather American.

My aunt and uncle, who put me up while I drive around Kentucky, live outside Lexington, near Athens. Once my surveys are done, they arrange for me to experience a day of French culture in Kentucky. Our 24 hours include:

- A symposium at the University of Kentucky, “Re-centering the Arts and Redefining Audiences: The Théatre des Champs-Elysées as Cultural Experience.” The Q&A session takes as long as the presentation itself. Scholars ask questions that require more time to pose than answer—not really questions seeking answers, per se, so much as opinions seeking audiences, raised in a tone of hostile, confrontational puzzlement. “It seems to me…” or “One can’t help but think…” With all the passive-belligerent manner and hogging the floor, the people wearing black, the scholars’ ostentatious slipping-in of French phrases (n’est-ce pas, c’est évident), the whole thing seems a bit like a Parisian dinner party, except without the wine, smoke, or fun.

- Spalding’s Bakery—if a Parisian croissant is a platonic ideal, so is a Spalding’s donut. If I lived in Lexington, I would need to go on a “No Forking Donuts” diet. They also sell “gooey butter bars,” which I decline.

- Several vineyards in the hills outside Lexington. Turns out that the French concept of terroir applies to Kentucky winemakers, too. One tells me, “People want my wine because it’s Kentucky wine. If it tasted like shit, they’d still drink it.” Another winemaker says, about the influence of the French: “People age in French oak for marketing, to say they do it, but only for the first year when the most flavor’s imparted, then they switch to domestic.”

- My cousin Robin, who lives in Lexington, tells me, “You know what they say about people in Paris? The ones born there are Parisians; the ones who move there are parasites.”

Paris, Texas does not, it turns out, exist in Paris, Texas—at least not the backdrops. Those pinnacles and mesas featured in the Wim Wenders film are found several hours further west or south. But none of the film was actually made in Paris, here in the state’s northeast corner, less than 20 miles from Oklahoma. Paris and the surrounding country are flat, open, desolate, and the trip from Dallas is a straight line on a two-lane road.

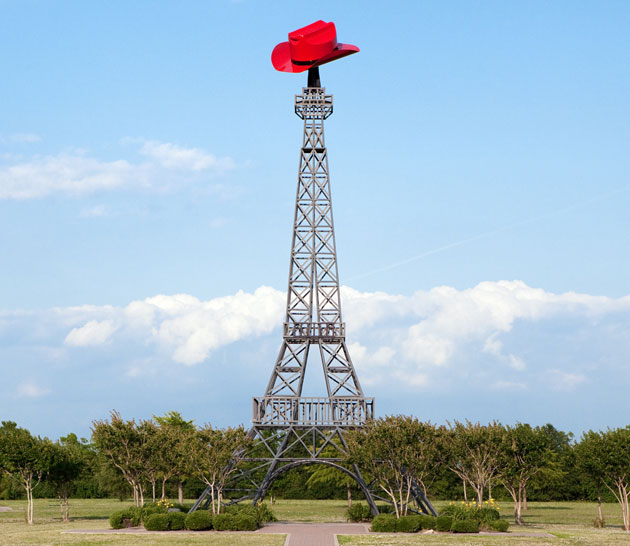

That afternoon—day six of my journey—the sky is humungous and blue, under which my rental sedan is a lone mouse. Other automobiles are mostly pickup trucks, and the trucks are mostly American, big rigs with stick figures to flaunt their family roster. Stores appear occasionally, and farms. But more often, nothing. I pass a cowboy church. It has a corral big enough for a hundred cowboys to attend service without dismounting. I run over two tumbleweeds. There are signs along the road advertising “Hay For Sale” and at least two—separated by half an hour’s drive—that say, “Hey For Sale.” On the outskirts of Paris is a Ford dealership as long as two city blocks, with at least 10 monster American flags that do not flap uniformly, but suggest a cavalry approaching. The motel I’ve booked is also on the highway, The Inn of Paris. Behind the reception desk is a poster of the French Eiffel Tower. On the counter is a bobble-head version of the Texan Eiffel Tower, which can be found here in Paris, about 60 feet tall and wearing a red cowboy hat. The base of the bobblehead is etched, “Bonjour Y’All.”

I’ve gotten in around 5 p.m. after a day of travel. I realize I’ve only eaten two Clif Bars that day in addition to a Bomb of Heaven Singing, what I call a Diet Coke with espresso. I ask the receptionist if there’s a decent bar nearby.

“There’s a Walgreens that sells beer across the street,” the girl says. Her hair’s flat and brown. She’s maybe 16, rigid and thin, like she’s made out of aluminum siding. “But you can’t drink there.”

In case you live in a large metropolis and haven’t seen these, people line up a row of stick figures on their rear window to demonstrate their family’s quantity—dad, mom, girl, boy, dog. (They’re all stick figures, though; to measure mass, other shapes than sticks would be necessary.) It’s a form of sentimentality I never saw in France—people in Marseille don’t fly French flags in their yards. Not that the French are shy about displays. They wear scarves for their favorite soccer team, carry banners for a union. But it’s not the same. America’s displays, our flag pins and rear-window college stickers, say “Look at me.” French displays, by and large, say “Look at us.”

“Well,” I say, “any chance there’s a bar somewhere?”

“There’s an Applebee’s. The food is good.”

“How about Tex-Mex?”

“There’s a Chili’s.”

“Any chance there’s a downtown in Paris? An old part of town with shops and things?”

“No. But there’s a mall over there,” she says, pointing to a shadowy rhombus in the distance underneath the highway. “They have like downtown stuff.”

I leave the girl with a “thank you,” not a “thank you very much, that’s terrific, thanks, super”—which is my way of saying I wish her boss would replace her with a computer.

The Paris Applebee’s, it turns out, is popular. The beer’s a dollar and people drink a lot of it. The bar, thickly packed, has every stool taken, mostly by big boys in hats, baseball or cowboy, with sunglasses pincer-ing their temples. Two booths are open. I perch in one, with a bad view of three different televisions, and order a Budweiser. A menacing guy in his forties sits down across from me. He’s twitchy, off-balance, possibly tanked. We’re about 14 inches from each other. He wears a goatee, black fitted Marlboro Racing cap, and a red-and-black hoodie that’s two sizes too big.

I call him, in my head, This Penis.

“Anyone here?” This Penis says after sitting there for a moment.

“Nope,” I say. “All yours.”

Commercials interrupt the football game. I decide to strike up conversation—and at the same time I think about also shattering a pint glass on my face because it’ll be more fun than asking This Penis to clarify his feelings about berets. But here’s the thing: If I do not engage him, what value will my survey have? If a pseudojournalist isn’t willing to start uncomfortable conversations, what good is his report? I will not be the coward of Frenchiness surveyors. And who’s to say This Penis doesn’t love or hate the French. Doesn’t have a poster of Robert Doisneau’s The Kiss hung up in his mother’s closet where he self-molests.

“It’s a tough angle,” I say, to break the ice.

“What?”

“You have to find a good angle to be able to see the game.”

This Penis lights a cigarette.

“Man,” he says loudly and getting louder, “I can’t get a fucking drink.”

A waitress passes, ignoring him.

“That’s not our waitress,” I say.

“I don’t even know that one,” This Penis says, with rancor.

Suddenly there’s a ruckus: Game over, Patriots win. People turn inward, to their companions. I say, “So I’m from out of town,” but then I falter. The guy’s expression, it’s now snarling…I lose courage. I start inventing things. “So I’m here on business. I’m a consultant. For IBM. Computers. So where’s a good place to get a drink?”

He takes a second to digest all of this. “What? Around here?”

“In Paris,” I say.

“Well, you’re fucking here, dude. This is it.”

Finally our waitress arrives and This Penis brightens up, puts a hand around her waist and orders a PBR draft, the $1 special. The waitress asks me, “You want something else?”

“What should I get?” I ask This Penis. Though why I say this, who knows, really. As if I need his recommendation. As if the Applebee’s house chardonnay is incredible.

“Fucking PBR’s only a dollar, dude,” he says. Once our beers arrive, though, he becomes conversational: “Most people start here.” He’s back to my question about where to drink. He spits under the table. “The Applebee’s is good, man. It’s real good—if you want to tie one on. Or Buffalo Joe’s. People start here or there, then move out. You can go to the Depot, but they’re closed Mondays. But when you’re shitfaced enough, we go over to the teen center.”

“People start here or there, then move out. You can go to the Depot, but they’re closed Mondays. But when you’re shitfaced enough, we go over to the teen center.”

I say, what?

“I said, get drunk enough, you go over to the teen center and act like idiots.”

At that point I chug my beer. He keeps going: “Tonight we’ll probably stay here for a while. You want another? Shit, where’s that girl?”

I tell This Penis no, I need to leave.

“Your family?”

Work, I say, big meeting. I ask him how much I owe. “They’re a dollar,” he says. He’s upset. I leave the money on the table. He stares me down as I leave, he says, “Whatever, dude.”

At Walgreens I buy a four-pack of Bud Light tallboys. I ask the checkout lady about French people. She takes 10 minutes to complete the survey, and I will admit I am impatient with her. Because I’ve had enough—enough engaging every stranger I meet, enough talk. France and the United States can implode tomorrow, for all I care. In my motel room, I turn on all the lights. Energy-saving bulbs—blue, depressing. I unpack, undress, though I leave on my boots and boxers because the carpet’s swampy and I wouldn’t trust the linens not to bestow on me gonorrhea. There’s an uneasy feeling. A strong desire to do something. The Gideons have left me a Bible—I open it and read and it doesn’t make an impact. A card from the motel urges me to save the environment, to leave my towels on the floor (like a child) and accept the reduction in service for my own good (like a child)—this from an industry that still installs bathtubs and lights its buildings like prisons. I get in bed and start watching Paris, Texas on my laptop. That was the plan all along, to watch Paris, Texas in Paris, Texas, but now my interest in the mirroring, to see what one lends the other, is gone.

Forty minutes later, watching Harry Dean Stanton lose, find, and lose his way again, I’m four times sadder. Which gets worse when I learn on Wikipedia that the movie was the favorite film of fellow suicides Kurt Cobain and Elliott Smith.

The beer is going, going….

Scraaaaaape—a loud noise outside. It’s after midnight. I hear it again, closer. Scraaaaaape. I look out the peephole. My car, parked outside the door, is the only one in the parking lot. I put on a shirt and go outside. There’s no one in the dark, just me and a shuttered restaurant, and a billboard that advertises gold bought and sold.

Those billboards are everywhere in America right now.

Enter a skateboarder, stage left, pants belted at mid-thigh. He grinds a railing—scraaaaape—kick-flips, and rolls into the darkness.

A minute later, I’m back outside, this time with my clipboard, going over to interview him, when I see his butt tattoo. It’s tribal latticework—the same kind found equally on Urban Outfitter clerks and Dartmouth fraternity presidents. But this is a first for me: It’s not a tramp stamp, but a crack tattoo, one that dips into and returns from his anus. Which I get to fact-check when he does an aerial.

That night, the highway is silent except for sporadic thunder. Goods are being shipped, business doesn’t sleep. There’s a neon sign to light my room through the window, like in a Wim Wenders film. Nearby, teenage girls are putting up with This Penis and other drunks. The remains of downtown have been shoved under the overpass, and the rebel, skating in the dark, chose to stick his pseudo-rebellion up his ass. This is Paris, Texas, and the reality is different from the dream—worse or better, at least unique.

Among the three words that people choose to describe the city of Paris, France (question no. 5), two words show up more than others: “beautiful” (33 percent of respondents) and “romantic” (20 percent).

But when asked to describe French people in three words (question no. 4), “beautiful” only registers 9 percent. “Romantic” gets 4 percent. Not because those notions don’t apply, I think, but due to Americans’ views about the French being more nuanced. We have more words to describe the French—84 different words, in fact—than we do for their capital city (60 words total). To be “Frenchy,” as Twain said, is simply more complex.

In 2003, NBC’s Tom Brokaw and Senator John Kerry had the following chat:

BROKAW: Senator Kerry, what about the French? Are they friends? Are they enemies? Or something in between at this point?

KERRY: The French are the French.

BROKAW: Very profound, senator.

KERRY: Well, trust me, it has a meaning. And I think most people know exactly what I mean.

One person who knew exactly what Kerry meant was an apple farmer I interviewed in Maine, who wrote down for me, when I asked her for three words to describe French people: “Very, very French.” But it’s that “meaning” of Kerry’s that I wanted to pin down when I devised this question. For example, if we look at the words people use to describe French people by categories, the beauty column includes “fashionable,” “stylish,” “elegant,” and “pretty.” Under romance, French people are described to me as “sexy,” “charming,” “passionate,” and “amorous.” (I do not include the person who wrote down, simply, “titties,” though I still laugh about it.) So the ideas of beauty and romance are important to Americans when thinking about the French, but they’re not predominant: Only 25 percent of words used to describe the French invoke beauty; 18 percent reference romance.

Arts and intellect come in higher: “artistic,” “sophisticated,” “cultured,” and related synonyms pull around 40 percent.

Then there are entries more unique:

- “Smoky, mushroomy, woolen”

- “Less than ambitious”

- “Humans speaking French”

For the most part, the words can be organized according to three prevailing stereotypes of France, as symbolized by Jean-Paul Sartre (“intellectual,” “opinionated,” “cigarettes”), Catherine Deneuve (“pretty,” “fashionable,” “enjoying life”), and Anton Ego, the acerbic Parisian restaurant critic in Pixar’s Ratatouille (“pompous,” “epicurean,” “close-minded”). This shook out as follows:

| French Stereotype | No. of Adjectives | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Catherine Deneuve | 46 | “Passionate,” “joyous,” “elegant” |

| Jean-Paul Sartre | 43 | “Smart,” “smelly,” “socially conscious” |

| Anton Ego | 21 | “Unfriendly,” “antagonistic,” “rude” |

But no one mentions anything linked to France’s history of militarism, its scientific minds, its superlative athletes. There were two mentions of “unshaved,” but I think that can apply to all three categories, even Deneuve. The main conclusion seems to me that “Frenchness” is a concept we can richly, if narrowly, describe, even when John Kerry can’t—being made of different parts sex, satisfaction, mind, and perspective. A promised life, whether or not the French themselves actually experience it, that is mostly about the heart, but also about the brain, with restraint and good manners occasionally sacrificed for joie de vivre.

So I’m beginning to think the notion of Frenchness has a lot more to do with the Americans who care about it than the French people they look to for inspiration, and perhaps little to do with France at all. Our fantasies of the other tell a truth about our longings. We age our wines in their oak. Slim our bodies to their shapes. Teach our children to be more like Jean-Luc or Françoise. When will we ever be good enough for ourselves?

“Anything that happens in the rest of the world,” one Texas business owner tells me, “happens 20 years later in Paris.”

The downtown of Paris, Texas, has extra-wide avenues and a majestic square. A few stores downtown are new—one sells kayaks—but many are empty, even caves. On the bigger buildings are blanched ads for Sky Chief Gasoline, Paris Cotton Exchange, Harold Hodges Insurance (“if it can be written, I can write it”). There are more old Coke signs than I can find places to buy Coke.

There’s also, not far from downtown, an Eiffel Tower wearing a red cowboy hat. I visit it my first morning. It’s smaller than I thought—I expected to see it in the skyline, but it’s shorter than a cell phone tower, surrounded by acres of empty parking lot that set a stage for dissatisfaction.

A 1992 study for The Journal of Advertising of French and American ads found that 24 percent of French ads use sexual appeal compared to only 9 percent of American ads (and 73 percent of those ads contained only women). Also, 23 percent of French ads use humor as compared to 11 percent of Americans. Another study, “Foreign Branding and Its Effects on Product Perceptions and Attitudes” (1994) found that, among American consumers, French names produce a more hedonic perception than English names. I think it can be safely extrapolated by now that Americans believe the French know better how to enjoy life.

Around the main square of Paris, there are at least eight antique or junk shops. I walk the downtown for two hours and come away with a sense of gloom—because when a downtown is mostly in the business of selling off its furniture, there’s a problem. Racially, the business district is whites, whites everywhere. I pass a statue paying tribute to confederate soldiers. The sun’s beginning to blast and already I feel dazed.

Among my interviews on the street, a young woman, a business owner, says about the French: “They’re culturally slow. What I mean is, they like the slow-paced lifestyle. They enjoy life.” A similar sentiment’s echoed by a middle-aged woman, a marketing executive wearing a black leather jacket: “They’re more lovers than fighters, you know what I mean? People here don’t identify with them. We have Texas pride. People from Paris—Paris, Texas—are doers. We get things done.”

Off the main square, I see a sign outside a one-story building that says OPEN. Inside is a dark crypt for unwanted paperbacks, piled in mounds. The owner, probably in his forties, is watching a movie on his laptop. He’s roundish, friendly, with pallid skin. His hands are salamandrine. I tell him why I’m visiting. “You’ll know about the racial crimes then,” he says, hitching up his glasses. He explains about several cases—a black man recently killed and dragged beneath a truck; a black girl given seven years in prison for shoving a hall monitor when, three months earlier, the same judge only gave a teenaged white girl probation for an arson crime.

“That kind of stuff,” the man says, “does not give very good press.

“People like us,” he continues, meaning him and me, “they want to leave here as soon as they can get out. Now, I’m one of those people who can entertain themselves. My father gave this building. The internet is my intellectual outlet.”

I visit the Chamber of Commerce to investigate Wendersgate. But everyone there is just so goddamn talkative and nice, professionally so—I forget why I came as I’m being inundated with the good news about Paris! Paris, a great place to be!

He continues, without me asking any questions: “So, how do I view people around Paris?” He takes a moment, arms crossed. “Provincial, parochial, narrow view.” A few breaths before speedy resumption: “The intellectual elite isolate themselves. Now, what are the problems? Rampant drug use—meth, crack. Lots of crime. Personally I love France. I’m part French myself. Have you seen Paris, Texas, the movie?”

I tell him I did the night before. He nods, saying, “You’ll have noticed it wasn’t filmed here. Now, it was supposed to be. Yes. Wim Wenders came to town, they were supposed to start, but he had an argument with the Chamber of Commerce about filming—you’ll have to ask them. But I met him, I sold him postcards. Nice guy, very nice guy.”

So, after a BBQ lunch from a trailer, I visit the Chamber of Commerce to investigate Wendersgate. But everyone there is just so goddamn talkative and nice, professionally so—I forget why I came as I’m being inundated with the good news about Paris! Paris, a great place to be! “A town so named…?” I say, but no one knows, not even the president of a local college, who happens to be stopping by. But Paris, I’m told, is very much on the up and up!

Two of the women, Mindy and Becky, explain that they, in fact, have been to the French Paris recently; they were part of a Texan contingent that visited France the previous March. And those Parisians…Well, they were so friendly. You hear the French don’t like Americans, everybody says that, but that is just not true. And all the Parisians wanted to know everything about what’s going on back in Texas. Listen, we even brought over a Stetson hat for the mayor, the deputy mayor, he’s just a little guy, he puts that hat on and is laughing—he said he looked just like JR from Dallas! Now the Parisians themselves, there were a lot of sophisticated, pretty people. Very mission-oriented. Not stuck-up, just busy. One weird thing, though? They didn’t have washcloths in the hotel. No washcloths! And fish for breakfast, that was tough to get used to, seeing fish in the buffet.

Becky says they’d gone to France because a French photographer, his name was Léo Delafontaine, had arranged the trip as thanks for a recent stay in Paris, Texas.

“People would feed him, have him over for dinner,” Becky says. “He walked, walked, walked everywhere. We said, ‘Léo, you’ve got to have a car!’ But he didn’t want one. So we got him a bicycle, and then he just rode and rode.”

Becky adds, “You know, one thing Léo said he noticed is that people in Texas smile a lot. People in France don’t, he said. Isn’t that funny? Say, did I give you one of our bobbleheads yet?”

My toughest question: “Name up to three current French artists (writers, painters, musicians, actors, etc.)” I figured that most people wouldn’t be able to name more than two. It’s worse than I expected. A barista in Detroit bristles when I ask him, as though I’m mocking his ignorance. A photographer’s assistant in Boise beats herself up for being unable to summon a single name. She’s not alone: 78 percent of respondents can’t name one.

The decline of French culture from heavyweight to ringside to concessions has been documented widely, not least by the French. For American purposes, the best guide is Donald Morrison’s 2007 Time article, “The Death of French Culture,” which caused a typhoon in Paris when it came out and was widely denounced. It also was subsequently expanded to book length. Among its facts:

- Few contemporary French novels find a publisher outside of France anymore. However, 30 to 40 percent of new novels published in France are translated from a foreign language.

- Only about 20 percent of French movies are released in the U.S.

- French auction houses account for approximately only 8 percent of public sales of contemporary art. Fifty percent occurs in the U.S., 30 percent in Britain.

For the most part, the book makes a convincing case that France has lost the position it once held of vast cultural influence. It includes a response by French intellectual Antoine Compagnon, who sums up France’s spot as being “a middle-ranking cultural power on the world scale, as suits our status as a middle-ranking economic power.”

Though Americans do like a good remake. Boudu sauvé des eaux was the basis for Down and Out in Beverly Hills. Le dîner de cons, with Thierry Lhermitte and Jacques Villeret, became Dinner for Schmucks, with Steve Carell and Paul Rudd. Trois homes et un couffin = Three Men and a Baby. La femme infidèle = Unfaithful. There are more, and more than a few French film people find this trend annoying.

To my question: Of the correct answers given, the most popular is Gérard Depardieu, the actor, with five mentions. Next comes the novelist Michel Houllebecq (three mentions). With two showings each are the musician and actor Charlotte Gainsbourg, the basketball player Tony Parker, and Renoir, who is dead and doesn’t count.

Getting one vote each: singer/actor/First Lady Carla Bruni; singer Mireille Mathieu; composer Pierre Boulez; actor Jean Reno; actress Marion Cotillard; actor Vincent Cassel; “the actors in The Artist”; and “the guy who tightrope-walked the World Trade Center.”

About Tony Parker: Well, I happen to see the art in basketball.

About Renoir, though…For the first couple people who write down the names of dead people, I point out that the question asks for living artists. Then I often get a queer look. As if it’s not common knowledge that Renoir has left the building, same for van Gogh, who has the bad luck of being both dead and Dutch—a woman in a Texas train station looks up with incredulity, “He’s dead?” So I stop saying anything, to see which lifeless artists are noted.

- Two votes each: van Gogh, Renoir.

- One vote each: Degas, Flaubert, Redon, Messiaen, Maupassant, Michelangelo, Rimbaud, Sartre, Hugo, Manceau, Louis de Funès. Also, Plato. And Julia Child. And the questionably artistic former French President François Mitterrand.

Wrong answers aside, no one writes down musicians like Daft Punk, Phoenix, or Air. No one mentions J.M.G. Le Clézio, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2008. No one mentions the artist Sophie Calle, or even Louise Bourgeois, who’s made her career in New York. And yet it wasn’t so long ago that French artists ruled the planet, and Paris was where, as David McCullough writes in The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris, people who “were ambitious to excel in work that mattered greatly to them…saw time in Paris, the experience of Paris, as essential to achieving that dream.” But it is America that now governs, for who knows how much longer.

- By the 1990s, 83 percent of Western Europeans between the ages of 18 and 24 were studying English in school.

- In the early 1980s, more than 50 percent of the Netherlands watched Dallas every week.

In fact, regarding Le Clézio’s Nobel win in 2008: While in Maine, I was in a lovely French bakery buried in Lewiston between car dealers and shops that advertised WE BUY GOLD, and while I was interviewing the bakers of the finest croissant I’d ever tasted, a customer told me she found this question silly, not even worth asking. France’s day was finished, she said. “If you think of literature, I don’t think France. They had their heyday. You look at the authors winning Nobels, they’re from other countries.”

Perhaps French culture’s bigger problem isn’t simply distribution, but marketing. If a writer wins a Nobel Prize but no one notices, it matters less. If an economy lacks demand, it struggles to endure. The longer stereotypes stay fixed, the faster they become barnacles.

For the rest of my stay in Texas, I racially and financially profile to avoid only speaking to white professionals.

This leads me to seeking out local hair salons. About half of the 11 businesses I look up are closed, but half aren’t. People in the shops give me recommendations to others. The so-far typical ratio of people willing to talk or fill out a form holds up, and the consensus about France and French people is pretty much what I’ve found elsewhere in Texas—Paris is a beautiful city; the French are decent folks—if pressed, then they’re beautiful/creative/smart/smelly/rude—but France and the French are cartoons having almost nothing to do with daily life. It’s what I hear in the poorest neighborhood, where I almost run over a pit bull while parking outside a one-chair shop, and in the fancy hair/nail salon I find in a strip mall.

One note: 100 percent of all hairstylists and barbers I survey in Texas know that Nicolas Sarkozy is the president of France, as compared to a national success rate of 51 percent. Maybe because many of them have TVs playing the news while they work. Or maybe because they’re simply better read, or required by the chatter of their customers to be informed.

The next morning, I finish my barbershop canvassing and stop on my way out of town at a bakery on Lamar Street for a croissant. Well, they don’t make croissants. But they do have vanilla cake, which I order to go. I pass a video shop near my motel, Family Video. They’ve just changed their big roadside sign to read, Midnight in Paris / Now in Stock.

Certain things must be noted while on a two-week reporting trip, no matter whether they relate to the journey’s purpose. The miniature horse farm advertising BUY ONE TODAY. The pretty maid at Howard Johnson’s with a jagged scar running from her left eye socket to the corner of her mouth, severing her left cheek, that she angles toward me while she passes in the hall, locking eyes with me, leering at me.

The man in the airport bathroom who gee-yips through his bowel movement. The man on the plane dressed like the Joker from Batman, reading a library copy of John Irving’s The Cider House Rules.

The no-secret-to-anybody romance between a Delta gate employee and a ground crew member in Phoenix—the latter in love, the former stringing the latter along.

Then there are details that actually pertain to my subject, like the Dallas coffee shop that starts the Amélie soundtrack the moment I walk through the door. Or the coffee shop in Portland, Maine, called Mornings in Paris that I pass one day randomly, where there’s a cute girl in the front window sitting under a poster of the Eiffel Tower. She’s sipping a latte. Looking delicate, hopeful, staring at the laptop that’s perched next to a blue Longchamp bag. Do I fall in love with the idea? Turns out she is a saleswoman of athletic sportswear. She’s never been to France, but it sounds nice. In fact, the one time she went to Europe, she begged her boyfriend to take her to Paris—and he was like, “Why would you want to go to Paris?” and I was like, “Are you serious?”

Seeing how I take a lot of flights in these two weeks—11 flights, 5,878 miles flown—I spend a decent amount of time noticing what’s on them. E-readers, for one thing—I stop counting them after my first flight, realizing that print is dead. But I do count 16 Louis Vuitton bags and 14 North Face backpacks. SkyMall, the in-flight shopping magazine, contains only one good with any French connection: “Mademoiselle Haute Couture,” a six-foot-tall lamp shaped like a woman with “the chic knee-high boots, trendy cocktail dress and accentuated curves that make her a timeless, always-in-style, fashion statement.”

Among its other cultural clichés, SkyMall also sells a Civilized Butler Clock, which wakes you up with the British actor Stephen Fry intoning one of 180 different witticisms like, “Good morning, Madam. I’m so sorry to disturb you, but it appears to be morning. Very inconvenient, I agree. I believe it is the rotation of the Earth that is to blame.”

But where is the lazy Mexican’s sombrero with built-in sunglasses? Where is Braun’s patented Jew detector? Other nations, you too can have your hackneyed figures, caricatures, and totem characters merchandised for sale in the American airspace—but you should know we do not offer a returns policy.

I email Léo Delafontaine, the Parisian photographer who went to Texas. Of life in Texas, he says, “We know very little of it in France except for clichés.” The following is edited and translated from the French:

Baldwin: So what was your first impression of Texas?

Delafontaine: It felt like a movie! Not the one from Wim Wenders, but a combination of American films. It was both very familiar and very new. After a few days, though, it felt like home.

Baldwin: How did the Texans respond to you?

Delafontaine: Before I’d left France, I contacted as many people as possible. Especially emblematic figures: the mayor, the fire chief. So I had a very clear idea of the people I would meet. At the same time, people in Texas were so open and welcoming—I met a lot more people than I expected. I guess they were happy to have someone from Paris, France, taking their picture. But I don’t think that explains everything. I really felt a kindness toward strangers that you rarely experience in France.

Baldwin: Had anyone met a French person before?

Delafontaine: Yeah, and I also met many people who’d traveled to France. Here’s a story: On my last day, I met an old woman, a Frenchwoman who’d lived in Texas for 30 years. We figured out that she used to live right next to where I now live in Paris. It was so unlikely and cool.

Baldwin: What do you think is the average American’s impression of France and French people?

Delafontaine: I imagine the French, just like Americans, have plenty of clichés in mind when thinking about one another. But the average American still looks a lot like the average French person—and vice versa. For my part, the only culture shock I had was the gun culture—this is completely foreign in France.

Day nine of 14. I no longer remember where I was two days ago. I do push-ups in motel rooms and hear myself talking—to whom?

Each hour, I detach myself from one of several forms of nationwide familiarity—another identical motel room, its paper tents urging me to save the Earth with dirty linen; another rented sedan with 12 cup holders but no iPod dock—and go straight into an intimate conversation with a stranger I’ll never see again.

Next stop: Paris, Idaho. Facing several days of long drives, I crave silence, isolation. I fly from Dallas through Phoenix into Salt Lake City and drive north. The mountains of the Wasatch Range are majestic company. Along the road are snow banks, green forests. The further in I get, the more the radio band drops away, eventually leaving only a classical station playing Dvorak’s stately Slovak dances. Road signs warn of falling rocks, roaming stock, crossing game. After three hours I’ve crossed into Idaho, overlooking the enormous Bear Lake. Sunlight falls like escalators from the cloudy troposphere. The lake is shockingly green, like sea foam that glitters, with mountains along the rim, as if the Alaska Range backed up to the Caribbean.

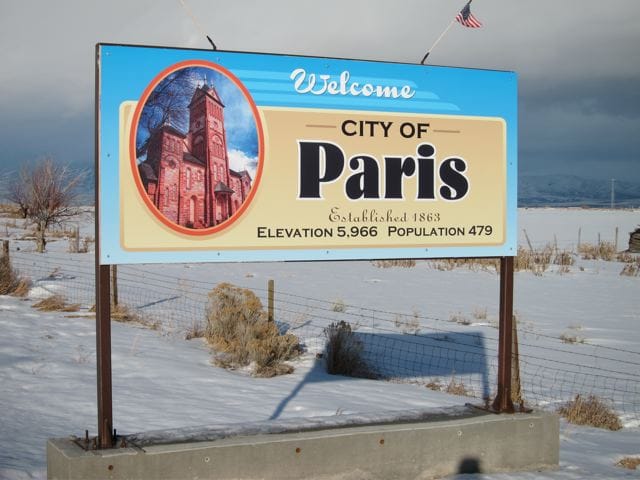

Located at 5,966 feet above sea level, Paris, Idaho, is a town of 479 residents. It was settled by Mormon pioneers and is surrounded by an amber valley of grain. There’s the occasional fence, collapsing barn, or string of horses, but mostly it’s prairie, snow, and hay bales. Paris, the name, has nothing to do with France: A land surveyor, Fred T. Perris, named the settlement after himself in 1863. When the town of Perris applied for a post office, the Postal Service decided the Perrisians didn’t know how to spell very well, and rechristened it like the French.

And people wonder why Idahoans distrust federal authority.

Paris has one main street. The only establishments open when I roll through are the gas station, town hall, town café, Mormon tabernacle, and post office—and the church is closed weekdays. Male-female couples wear matching blond mullets. Dusters are appropriate coats. In the café, a mother and daughter are cleaning up the lunch service. There’s a guy in a corner painting a wall, otherwise it’s just them and me. I sit down at the counter, order coffee and two cookies. The women listen to my pitch about the article and tell me it’s interesting—but it’s obvious they don’t want to participate. They’re too polite to say no, though, and instead they say, “We were just about to eat our dinner; this is the only break we get before the rush.” And I say, “That’s OK, I’ll wait”—like an idiot.

To my credit, I realize what’s going on two seconds later, and start to leave. But I’ve ordered this coffee, which comes in a large ceramic mug—enormous and nearly boiling; it steams like a geyser. Plus, they haven’t given me a bill. I try to slurp the coffee; it burns my lips. The women uneasily arrange a table right behind me and start eating pasta dishes and whispering to each other. Meanwhile I’m sitting next to them on a very tall chair facing away, being steamed by my drink, with no smartphone, no book, no magazine, just my awkwardness and their murmurs.

big

Five minutes after which the painter, Ronnie, approaches, earning a cold eye from the women—either because he’s not working or because he’s talking to me. Ronnie’s lanky and shaggy. His long blond hair parts in the middle. He has a tan, weathered face and a horseshoe mustache. We get talking. He’s a big fan of France and French people—big fan. “Never met any, but I figure they’re probably just like us—some good, some bad.” He starts on the survey. What impresses Ronnie, he says, is how they’ve figured out health care. He’s missing a couple teeth; when he laughs, I can see black holes in his smile. “If I was going to export myself, that’s where I’d go!”

The sunset outside turns the mountains purple. Snow clouds roll in. Two hours later, after driving around the snowy streets, I wind up in a bar sitting between cowboys and hunters. The room’s dark, filled with smoke, silent except for the television. Occasionally someone balls up a cellophane jacket from a soft pack of cigarettes. Any men not wearing flannel are wearing suspenders. The one guy without a mustache—besides me—wears a camouflage hat and vest. There are two televisions, one playing a basketball game on ESPN, one playing TruTV (“We did dumb first. We do dumb best.”) I introduce myself to the dude on my right. He’s a cowboy, the real deal, with a big hat, tattered windbreaker, and rotten teeth. He goes where the work is, he says, and prefers to be on a horse than off.

He says, “You a businessman?”

I take a minute to explain what I’m doing there.

“Man,” he says, “no shit!”

The bartender, a pretty blonde, gives me a Bud Light—it’s what everyone else is drinking, except for one guy with a moustache that hangs below his jaw, whose drink is pink and bubbly. She asks to see my ID. I make a joke about how I only get carded on days when I shave and the guy in camo on my left pulls out his wallet—“Check this out,” he says, “I just got my new license today. Look at that—it’s a flimsy piece of shit. My conceal-and-carry permit’s like twice the size of that bitch.”

He asks what I’m doing, and for the next 10 minutes I tell my story and he says things like “No shit” or “Son of a bitch!” and then ropes in the guy to his left—“Hey you asshole, listen to what this guy’s here for, he wants to talk to you!” And so on until I’m adopted by the bar.

In 90 minutes I drink six beers, just like everyone else, then apologize for leaving, promise to return, and stumble over to a Mexican restaurant across the street. The sky is snowing. I order nachos and write down five things I’ve learned:

- Idaho rules.

- Boise State football rules.

- “Son of a bitch,” as a noun, is flexible. At one point I asked the cowboy to my right if he minded if I smoke. He said, “I want you to smoke the hell out of that son of a bitch.” He also told me a story about how, for example, during a cattle drive, if some of your cows rush into a gully, you and your horse will have to follow them down, which means you’ll run the risk of getting stuck, which is annoying. Or, as he put it: “Man, when those sons of bitches get fucking rammed down in that shit, well, you bet your ass is stuck riding through that bitch, and that shit sucks—you’ll be fucking stuck in the son of a bitch all night if you’re not careful. And it’s not like the cows feel fucking shit, sons of bitches, they got hide that’s four inches thick.”

- A tour bus used to come through Paris every year filled with French people on their way to visit Yellowstone National Park. Everyone knew the French had arrived because they’d order wine and steaks for lunch. “Big portions, too,” one guy says admiringly.

- Concealed-carry-permit guy: “Well, you’re not going to like what I have to say, but I’m an American, America first. But I’m also a history guy. France and America go back a long ways. Don’t listen to that shit on the news, about freedom fries and crap—that’s bullshit. The French fucked themselves. It’s because they didn’t back us up in Iraq—and I get it, I see how Chirac wanted to position France on Iraq, the geopolitics. But we’ve done a shitload for them over the years, I’m talking back to the Louisiana Purchase. So French people, in general? They’re just like anybody else—most people are friendly, 10 percent are assholes. The rest is just politics.”

The morning I leave, I mail a few postcards from the Paris post office and interview the postmaster. She tells me how a tour bus of French people used to come through town annually on the way to Wyoming.

I say I’ve heard that, in fact.

Oh well, she says. But she has a story about the tour guide being quite the character. “He’d show them around town, and he always made time to visit the post office to say hello. I used to see him every year. He’d say to me his little joke in front of everybody, he thought it was so funny: ‘We are the Parisians, and you are the parasites!’”

She says they don’t see the French so often anymore now that the buses started taking a different road up to Yosemite.

To reach The Paris Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas I drive seven hours west across Idaho through three snowstorms, and fly from Boise Airport to McCarran International in Las Vegas. There’s a brief stop to pass around my survey in a yurt among Boise’s elite—a fancy 40th birthday party some friends have invited me to, held three hours north of Boise that requires a mile of snowshoe-ing into a state forest to reach. Around midnight, the yurt’s loaded—both in terms of capacity and collective drunkenness—and an attractive woman starts showing off her new boobs. One guy runs over. He says he didn’t catch the show. She flashes him. He asks to see them again. She flashes him again. He asks to see them one more time. She flashes him one more time. He asks to see them again. She flashes him again.

The last time I saw live boobs that weren’t my wife’s, I was at a friend’s sister’s 40th birthday party where the birthday girl demoed new lingerie and did a dance for the party that showed off quite a bit.

That was in the south of France.

Las Vegas has plenty of burlesque, is the Burlesque Version of America Incarnate. But The Paris lacks showgirls—you’d think they’d have a little can-can show. It is, however, otherwise amazing. There is an actual sizzle in my brain, a neural flush when I’m floored at the doorstep, as I step out of the cab into the blue desert evening and stand in the glowing entrance, gazing over a crowded, glowing recreation of Paris’s Left Bank, though with all the scooters and bicycles replaced with flickering slot machines. It is Paris, densely. Paris as we imagine it to be. In the real Paris, you can’t simultaneously stand within 30 feet of the Arc de Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower and the Boulevard Saint-Germain, but in The Paris, yes, you can. The ceiling is painted French blue sky—a permanent Parisian April morning. And it all could be a soundstage left over from An American in Paris, but with a cast drawn from the drunken, drugged, and/or semi-mobile populations of three frat houses, two senior care facilities, and a Chinese wedding.

Elsewhere in Las Vegas there’s the Luxor (Egyptian), the Excalibur (medieval), the Bellagio (Italian). I’ve heard Las Vegas described as a cruise ship stranded in a desert—and that’s true only if the gangways are teeming with all the world’s clichés. The Paris is similar. If a miniature city could be made from everything Americans attribute to Frenchness—the real, the cliché, and a few hundred cocktail bongs shaped like Eiffel Towers—that would be The Paris.

The Paris cost $785 million to build. It occupies 24 acres. There are close to 3,000 rooms. The night it first opened, in 1999, they even got Catherine Deneuve to flip the switch to turn on all its lights.

It will take me six hours of exploring before my buzz turns to blackness, anguish, and lung fatigue. But first there is the pleasure of discovery.

At the front desk, the woman who’s checking me in has a French accent. I ask her a question in French, which she doesn’t answer but says instead that since I speak French, we may as well use French for the rest of my check-in, so that I can practice, n’est-ce pas? This results, I think, in her screwing up my billing address, but also giving me a room upgrade with a better view: a front-row window onto the biggest Eiffel Tower in the United States, 46 stories tall, a half-scale replica.

I ride the elevator upstairs to unpack and shower. My plan, concocted on the flight to Vegas, is to see every inch of The Paris over the next eight hours, until 2 a.m., at which point I will sleep for four hours before getting up to catch my morning flight home. But in the time I have, I have the vastness of The Paris to register. The hotel contains a casino, a nightclub, two French cafés, and six French restaurants. I will see it all: a French crêperie selling ham and cheese crêpes for under $10 and a French sports bar selling a $777 cheeseburger (“a Kobe Beef Maine Lobster Burger, topped with caramelized onions, imported Brie, crispy prosciutto, and 100-year aged balsamic vinegar and served with a bottle of Rosé Dom Pérignon champagne”). There’s also a two-thirds replica of the Arc de Triomphe that is stunning, no kidding, right outside the lobby, and free to visit, ogle, read the names of former French generals inscribed on its walls. Whereas the faux Eiffel Tower costs $22 to summit during the evening rush hour, when the casino fills with visitors wandering in from the Strip. Though for $6, at any time, you can buy an Eiffel Tower cocktail bong available in margarita, piña colada, or cosmopolitan flavors, and carry it to the gaming tables.

I change into a clean sweater and stuff a dozen questionnaires in my pocket. The TV in my room is tuned to an in-house channel: a tall man in a blazer giving instructions in case there’s a fire emergency. I listen, but it’s hard to follow. He speaks with a French accent so odd, either fake or Canadian—“fill your bathtub with water” is pronounced “feel yoyer baftobb weeth wahtayr”—he might have learned the language from a Kentucky library book.

Not until after 1.5 loops, sitting on my bed in stupor, do I realize he has the precise accent of Peter Sellers playing Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther movies.

If The Paris has one unifying aura—more pervasive than the smell of cigarettes, which can be openly smoked—it’s of Frenchness rather than French; an extravasation of Frenchness from every square inch that is both wonder-inspiring and, after only a little while, annoying.

So, The Paris: To start, it’s all in French. The door markings, the room names. More than any of the other Parises in America that I’ve visited, here tribute is paid not just in deed, but words: L’Hôtel Elevators. Les Toilettes. The bigger conference rooms are named Concorde, Rivoli, and Vendôme. The second biggest conference room is called Champagne. The third is Versailles and the staff there who I ask to pronounce it say the name in the French manner, not the Kentucky way. Everywhere are street signs to point you in the right direction for Le Business Centre, Le Champagne Slots—but they’re useful not only for assistance but assurance that the facsimile of Paris never ends. Inside and out, the hotel is coated by Franco-ectoplasm. It’s shock-and-awe decorating, sheer cultural immersion—tulle, lampposts, fleur de lis, and enamel signs. The employees are trained in French banter. French pop fills the air (I don’t recognize a single tune, it’s so French). If The Paris has one unifying aura—more pervasive than the smell of cigarettes, which can be openly smoked—it’s of Frenchness rather than French; an extravasation of Frenchness from every square inch that is both wonder-inspiring and, after only a little while, annoying. Like when your cousin Bill visits Europe for the first time and returns all-knowing, suddenly wearing an oddly tight T-shirt, saying, Listen, it’s amazing, it’s like this.

I half-expect to run across a childcare attendant dressed like Astérix.

Some parts of the hotel over the next eight hours will be closed, even when I shove the doors hard: the wedding chapels (there are two of them), the spa, the pool store. But some doors yield to shoving. I’m able to experience the Soleil Pool, a two-acre octagon dug beneath the Eiffel Tower. Le Bar du Sport—good for a $6 beer or two. Near Le Centre de Convention, I study portraits of Louis IV and Marie Antoinette in a chandelier-filled hallway that connects the casino to the ballrooms—the biggest of which, at that moment, features a man giving a presentation to a room of 200 business people. There’s a large ice sculpture by the door. It’s melted too much by that point to resemble anything, suggesting the event is almost over, but I sneak in anyway. It’s an advertising seminar. Something to do with mattresses. The man brags about a recent success his team experienced with viral marketing—he’s referring to a YouTube video he’d played just before I slipped in. “In the case of those 40 million viewers, it’s not how many, but who many,” he says. He pauses. “Because these are people seeking out our ad. They went to YouTube, a friend sent them a link, they’re sending that link on to other friends. It’s a reasonable assumption that these are better unique viewers.”

I leave the seminar to visit a restroom across the hall. I’m standing at a urinal when I hear a woman’s voice—behind me? Speaking in a foreign language? I worry it’s a janitor. “Someone’s in here!” I shout. A man looks at me funny from the lavatory. But the woman keeps talking, in French—as a matter of fact, she just said she wants to go to my bedroom. I go into a stall, lock the door. A moment later, a man’s voice says quietly something like, “Here are a few French phrases you can use to better enjoy your stay in Paris,” then there’s the woman again.

It takes me about 10 minutes of sitting there, trying to listen and breathe through my mouth while various men coulent un bronze around me, to record the following: