Painting the President

Twice the official portraitist of George W. Bush, painter Robert Anderson explains what it’s like to build a relationship with a president, separate the man from the legacy, and struggle with his smirk.

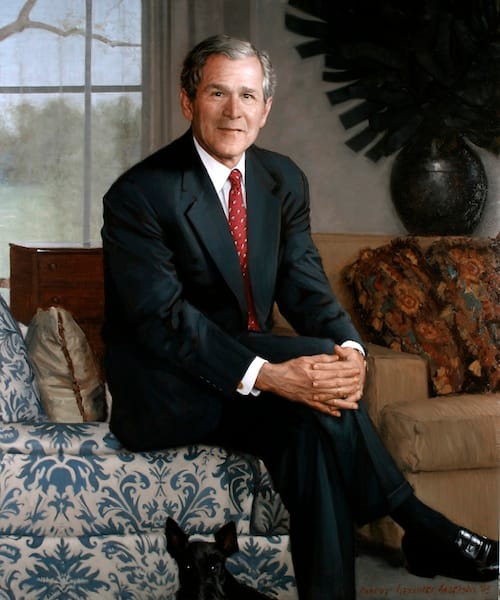

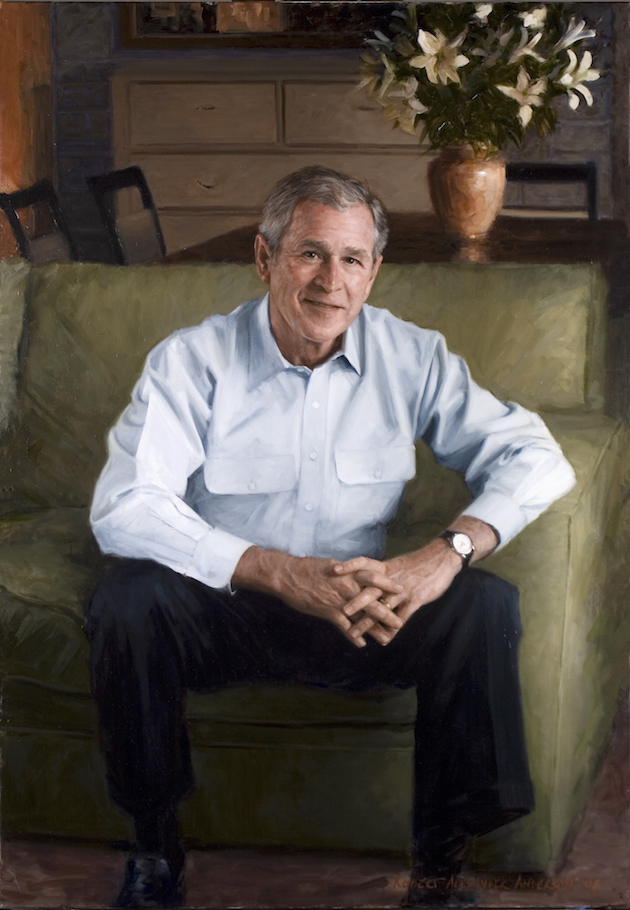

Robert Anderson has painted George W. Bush’s portrait twice: once for the Yale Club in New York City in 2003, and once for Washington DC’s National Portrait Gallery in 2008.

I recently visited Anderson at his riverside studio in rural Massachusetts to ask about his work and, eagerly, what it’s like to look so closely at the former president’s face. We sat on his porch for a few hours, drinking beer, watching egrets stalk in the marshgrass and kingfishers fire themselves into the water.

Anderson has visited the Bushes at Camp David and their home in Crawford, and was invited to Bush’s 60th birthday at the White House, but he is polite and cautious about their privacy. We talked mostly as two artists discussing a couple of important paintings.

Anderson has the parted silver hair, severe eyebrows, and sharp blue eyes of a military man (he used to be in the Navy), yet is often poetic in a way that makes his path into the arts seem inevitable. He has a soft voice and turns his glasses thoughtfully in his hands as he talks. When I first asked him about the National Gallery portrait, he said, “Of all the paintings that there are to do in this country, that was the plum of plums.”

How did you get the commission for the first portrait of the George Bush?

There’s a room on the second floor of the Yale Club that has portraits of all the presidents who have been to Yale. I wrote the Club saying, “I know you’re going to be commissioning the president’s portrait. I’m a member. I’m a portrait painter. And I was a classmate of the president.” I didn’t hear anything for the better part of the year. Then, one day, I’m working away at the studio and the phone rings.

This voice said, “Anderson, is that you?”

I said, “Yes.”

He said, “This is George W. Bush. I’m calling you from Air Force One. I’ve got this stack of portfolios at my desk to look over, and I picked up the first one and said, ‘Hey, I know this guy.’ You’re still doing great work. Are you interested?”

I said, “Let me think about it for a nanosecond. Of course.”

He said, “Come down to Washington and we’ll have lunch. I might lose the connection until we’re airborne. I’ll call you back if we do.”

That’s not as formal as I imagined.

He’s immediately accessible. He’s a Texan. Texas, the place, is in his bones. Not in a gunslinger way. In a charming way.

I started the Yale portrait the day we went into Baghdad. I had the canvas, I had the pose, I had everything all ready to go. First stroke to the canvas, I’m watching the bombs on television. Never had I stood before a more blank, more intimidating canvas at that moment. I later had a conversation with the president about what he had gone through to arrive at the decision to go in. I’ll tell you about it some other time. It was very carefully, agonizingly thought out. It humanizes him immensely.

Watching the engagement on TV, I felt like I’d then hitched a ride on something way bigger. At that time, we didn’t know what the outcome was going to be; we didn’t know if Saddam was going to be finished by the end of the day, which is what the president hoped then, or whether it would be another Vietnam. We had no idea. I felt connected to a significant world event. I knew I needed to be paying close attention to how I was handling all of this.

How much did you paint that day?

Just the under-painting [washes of color and gestural outlines of form to be overlaid with finer brushwork—ed]. It didn’t make me paint any faster. I probably felt more intensity. But, I’d lose myself between right brain and left brain as I was working on it. The right brain is steering the left brain. The right brain is guiding me through the brushstrokes. I know these materials so well. And then there’s this backdrop, and I’d shift over and think, Oh my god, there are bombs going off. And then I’d think, I need to get my turpentine out because I need a light accent here, I need to balance that.

At its best, in moments like that, I become the vehicle. The more I disappear, the more invisible I can become, the better. Making something feel like what it is instead of what your preconception of what it is—like the ‘how do I make that eye look like an eye?’—the eye already is. Your job is to reveal it. There’s some spiritual element to it. And then, you withdraw from the room, and it exists on its own. That’s one of the very coolest things about painting. It’s still a mysterious process to me; I don’t feel like I have full control over it. It’s like getting on a horse that’s not fully broken. You know roughly where you’re going, but the horse will have its way. You’re trying to depict the randomness of nature, in peeling the shell away to try to get underneath.

At the unveiling of the second portrait, the President said, “I was talking to Bob about the process of painting this portrait, and Bob said that he seemed to have some trouble with my mouth. That makes two of us.”

That’s a good way to describe the art in representational painting.

Like a sculpture, you’re removing what isn’t. I’ve always loved that. It’s like Robert Frost saying that there’s a big difference between having a poem to write and having to write a poem. Isn’t that it?

You read a lot of poetry?

I wrote poetry for a while when I was in school. I loved finding the right burnished word for the thing. We’re all looking for that.

So what did the president say about your painting?

At the unveiling of the second portrait, the one for the National Gallery, he said, “I was talking to Bob about the process of painting this portrait, and Bob said that he seemed to have some trouble with my mouth. That makes two of us.”

His mouth?

There’s that little thing with the upper lip that can look smirky. He’s aware of that. He would say, when people were photographing him, “Is this looking too smirky?” There’s such a subtle difference in what comes off as a smirk and what comes off as just part of his humor. His sort of elfin humor. It’s just kind of how he looks. The caricatures that you see of him—his ears pointy and sticking out—it’s all such an exaggeration. He’s a pretty handsome guy. I think it’s possible that I painted his mouth a hundred times before I got it.

Just wiped it away?

Yeah.

How long did that portrait take you?

Probably three months total. Shorter than the first one.

He didn’t sit for that time, right?

I work from photographs.

Have you seen the president’s paintings? I think he’s painting from life.

I heard from a friend of his that he’s got some painter who comes over and spends a few hours a day with him. My guess—not because he said anything to me about it—but my guess is that when you go from having so much on your plate, as a president does, and then you find yourself stepped off the porch and in civilian life, you’re trying to figure out what do with your time, how to build something meaningful into your leisure. He had the presidential library at SMU, but he’s got to decide what he wants to do for the next act. Whether painting is something he really gets fire in the belly about, or whether it’s something recreational, I don’t know.

He did some pretty provocative and personal paintings. I don’t how they got out on the internet. The bathroom series. The painting of his feet in the bathtub. That’s pretty unusual stuff. I think he was just finding a way of expression. He’s not really a buttoned-up guy, but he had to be more buttoned up than is probably his nature. He had to be careful about what he said. And where and when. This was letting his hair down a little bit. He’s really not that self-conscious. He’s up for anything.

He didn’t want to be an ex-president who was trying to engineer a legacy that was contrived or reshaped.

To me, his paintings are funny and scary at the same time.

They are. Do you know John Currin’s work? He’s got this Dutch luminous way, but his figures are all caricatures. You know the one of the women standing over the turkey? The turkey is the most sensuous fricking turkey I’ve ever seen in my life. The blue in the leg.

And Bush’s paintings have the same quality?

They’re fun. They’re just fun. Self-deprecating. He’s got a painting of himself looking in the mirror in the bathroom. This is the president. But he’s not the president anymore.

I remember hearing that oil paint was invented because it was the closest thing to flesh. Are his painting in oil?

I think they are.

There’s something about painting his own flesh that breaks some big barrier between the public and the president.

Maybe he’s trying to get beneath his own surface. Maybe he’s delving into some self-discovery. See what kind of vocabulary he could build to reveal something about himself. Or maybe he’s just having fun with it—like the portrait of Barney, the Scottie.

But it’s an interesting point—the barrier—in terms of my portrait. As Anders Zorn did with Grover Cleveland, and every other painter presumably did with every other president in the National Gallery, the painter builds a relationship with the president, and so the president has to be mindful of what he would be revealing to the painter. How much of the pose is carefully crafted to reveal only what the president wants the painter to see, and the way he wants to be portrayed. It’s kind of engineering your own legacy. With Zorn, you feel like Grover Cleveland is not the president, but a guy with a messy desk and great-looking brushstrokes all over.

I had a conversation with the president before the first painting—in 2002—about legacy. He said that there are some former presidents that are very conscious of their legacies. He didn’t want to be an ex-president who was trying to engineer a legacy that was contrived or reshaped. He said, “I’m very aware of how I’m perceived in the media. Different people have very different feelings and thoughts about what sort of a president I am, but all I can do is follow what I believe is the right course for the country. I have principles and standards that have guided me so far and I have no intention of straying from those. I’m not going reach back and try to recalculate or reengineer them. My legacy will be whatever it will be. It might take a generation or more before it all settles down. And some of the political issues that had so much flame to them are going to settle themselves into perspective, and will be a part of how I’m regarded.”

He said, “I have other responsibilities. I can’t spend time trying to reengineer my legacy.”

Bush is remembered so fondly in some circles, and with loathing in others. That didn’t affect how you approached your painting? He might be the most charged figure of any of your portraits.

I don’t think I was affected by my awareness of how different camps regarded him. I didn’t expect to change any minds about him one way or another with a portrait. I simply wanted to paint as fine a painting as I could, and to convey in an apolitical way something personal and true about George Bush, the man. Art can be transcendent. Something of an equalizer.

The Bush administration wasn’t very kind to the arts. How do you feel about that, as a painter?

I have strong feelings about federal support for the arts. I don’t really like individual grants. I love arts education for kids. But, for example, the NEA has a board that chooses from lot of people applying for the grants. It’s just so random that it doesn’t feel fair to use taxpayers’ money to support individual artists, where the benefit doesn’t accrue to everyone. I’ve always been uncomfortable with that.

If you had a conversation with him and then went your separate ways, you left with a sense that he really cared about what you had to say. You ended up feeling like a million bucks.

Though, recently there were a number of articles about government officials paying for their portraits with government money.

My painting for the National Gallery was donated by a few Oklahomans. The Yale Club paid for theirs out of their bank account.

So what do you think your portrait at the National Gallery says about president Bush’s legacy?

I think, uniquely, because I knew him when we were in our twenties, I probably brought a quest for familiarity to the painting. I’m not positive of this, but I would wager that my relationship with him, having spanned several decades, was unique to the dynamic between painter and president of all the portraits in the Presidential Gallery. I had a person that I remembered from my twenties, and I could see that person in his 21st century iteration. I could see the roots of what he was back then showing through in the person sitting before me. The White House photographer said, “I’ve rarely seen him being so relaxed.” He seemed very much like his old self. There are many dimensions to him beyond his old self, but his old self was underneath it.

He relaxed into a comfort zone that took him off-camera. He’s at his best when his sleeves are rolled up, when he’s in conversation, engaged, when he’s not starched and being carefully managed or scripted. Easy. Affable. A focused sort of relaxed.

Have you read Wallace Stegner? The Angle of Repose? In it, there’s a human metaphor in what happens when a backhoe dumps a load of coal in a pile, and the coal cascades down and settles into a stable pile. By its own nature, the shapes of the pieces, it seeks the angle of repose. I’ve always loved that idea, that you start out sitting straight and rigid, and then everything relaxes, but still, you stay engaged with eye contact. You’re more focused. It reveals more about a person to get them in a relaxed pose as possible.

And you caught him in the angle of repose?

I think that pose is typical of him. I have a lot of classmates from Yale who’ve been to the gallery and they say, “You’ve nailed the painting. There he is.” I think if you cover up the head of that person, people who know him would say, “That could be George under there.” The body language has a lot to do with a likeness. As much as a likeness in the head.

I think there’s that, maybe not intimacy, but something very personal, about having a sitter in a painting look you in the eye and make you feel as though they know you.

Do you remember what you were you talking about when he sat for you?

Not really. Our kids. Outside, a Secret Service guy was whacking golf balls for Barney to chase, and we were laughing at that.

I’ve heard that he’s magnetic.

If you had a conversation with him and then went your separate ways, you left with a sense that he really cared about what you had to say. You ended up feeling like a million bucks. He was like that with everybody—not cherry-picking. Everybody had their stuff they did in their early twenties. That whole frat-boy thing—his free spirit was not shaped by alcohol. If he were sitting here chatting with us, you’d know you were in the presence of somebody that was different in a really important way. He has a very powerful sense of his family’s place in history. His father’s place in it. Deep convictions. Religious. He’s always been that way. I’ll tell you some stuff, off the record. Not now. I want to be respectful of some of the private things.

You’re in the tradition of artists who painted royalty, kings, men of power. But those portraits, from the 17th and 18th centuries, are all about distance. About telling the viewer the king is untouchable, greater. Your portrait does just the opposite.

Yes, but I was respectful of his office. He was George to me in school, but I had to be careful in the company of others. When I was with him and Mrs. Bush, it was always Mr. President. But when we’re by ourselves, we can be more familiar, all in our angles of repose.

I suppose I haven’t thought of this until you asked the question—of how important to the success of the painting it was to not have the glass separation. No separation, no boundaries between us. I brought to that portrait the principle of getting connected that I try to bring to every other portrait, and which I’ll bring to every one yet to be painted. I like the idea that someone would look familiar to a viewer if the viewer didn’t know them. I think there’s that, maybe not intimacy, but something very personal, about having a sitter in a painting look you in the eye and make you feel as though they know you.

What colors did you use for George Bush’s eyes?

I don’t remember what color I used. But if you get the value right, and you make it gray green blue brown, you can make it work. I saw him after he sat for the portrait and used some cerulean and sap green.

Blue-green?

Sort of multicolor. There are flecks of gold. It’s been a while since I looked into his eyes. I don’t regard myself as a colorist.

How about his skin?

Well, I have to be mindful of it, but I think of myself more as a draftsman. I like grays.

The other day you told me a story about walking through the National Portrait Gallery with the president.

It was in the morning, before they let the public in. We walked through with the director of the gallery. The president and I were looking at, or for, different things. I was drawn to the painters I admired; he was drawn to the presidents he admired. I stopped at the Zorn. The one thing I remember the president saying, just before we were about to leave, was, “I can tell you one thing that I know about this portrait: it’s important to me that this not be the largest portrait in the collection.” He wanted it to be good, but not to command attention because of its size.

At the time, my father had been very ill with cancer. I left him not being certain whether I’d see him again. But he said, ‘You go. This is a big opportunity.’ He knew my wife and I would be staying at the White House. After the president and I had gone through the gallery, the director headed us toward the freight elevator. The elevator operator pressed the button, and nothing happened. She pushed it again, and nothing happened. The president joked with her so she wouldn’t get too upset about it. Finally, Secret Service came in and said, “Mr. President, ladies and gentlemen, we’re going to go out the back door of the elevator and downstairs.” So we all filed out, went downstairs, got in the limo, and headed back to the White House for lunch. On the train home, I called my sister to see how my dad was doing. He had died at about the time the elevator couldn’t move.

Who knows. I had this sense that he swept through Washington on his way to the hereafter. And said, “I’m here with you.”

I shared that moment with the president, and he wrote me a phenomenal letter after that. He’s a man of enormous heart.

How did you sign the president’s portrait?

On the front. In paint. I’ve been accused of making my signature too small, but a painter knows where to look for a signature.