Picture Me Not Posting

If distractions poison a writer’s ambitions, then surely a summer with no internet access is the antidote?

I went to a place without the internet because I wanted to live life deliberately.

This, for example, would have been something to tweet.

Or edit any number of times, lopping off prepositional phrases until the word count pulled up from a negative.

But I wouldn’t be sending the thought away. I was in a countryside home at the edge of the Morvan Forest in eastern France, an hour outside of the city of Dijon. We’d made our permanent home in Dijon for the past few years, it being my wife’s place of birth. As the American newcomer, I’d always viewed it as slightly provincial. But compared to here it appeared to me as a burgeoning metropolis. We’d come, then, for the summer to the truer, deeper province. This remote country village had no commerce, no stores or bars, not even a bakery. Just a church dating back to the 12th century and scattered farms and residences, all surrounded by pasture. The house we settled into had no television, no phone line, and no connection. Some neighbors, we could tell, had wi-fi, but they kept to themselves enough that it would have been an affront to request the password.

So I would relax here with my wife and two daughters. This would be healthy, I told myself. It had to be. I had a higher calling.

We had wild blackberries to pick, for instance.

We walked up the hill behind the house, beyond the cows grazing on the slope. As my daughters led with empty baskets in their arms, the locals we passed, bent over their vegetable gardens, straightened upright to comment that the berries had ripened early this year. They advised us to try the patch of brambles hanging over the pasture’s low stone wall just over the crest of the first hill.

So we heeded the expert advice and stopped there. As we plucked blackberries the size of gumdrops, our hands turning dark violet, I saw the village below and the parceled land spreading beyond it. From here, only the wind and the church bells at the top of the hour interrupted the silence. Lofty ideas began occurring to me.

One was: Wow, getting away is a real inspiration.

Another: I need to tell everyone about this.

I’ve molded the recent years of my life into that of a stay-at-home dad, an American expatriate and a writer. Converging at the intersection of too many conversations with children, second-language fatigue, and the longtime urge to transcribe thoughts into sentences is an online presence that I perhaps take too seriously. Social networks and the comment sections of beloved sites therefore function as an essential tether for me.

But, without warning, I found myself craving a break. I noticed I wasn’t the only one.

The seeds for my own writing that would sprout during my time-out would surely blossom into something that would have never been possible with my refreshed Twitter page adjacent.

I’d detected weariness from the web in the utterances of my friends and online acquaintances. Some had grown cynical and hostile in what, only a year ago, were breezy exchanges. Others seemed to be offering perfunctory “likes” based on the fact they’d “liked” another friend’s post and thus had an obligation now. The same videos and articles were re-circulated over the course of 18 hours, only to fall away like they’d never existed, replaced by the next unrelated sensation—all by the time we were all staying up too late. The voices I truly admired online expended their most crackling energy to decry our use of the platform they stood on. The social web was doing awful things to our children, our communities, our relationships, our brains. Just repost this podcast and we’ll prove it.

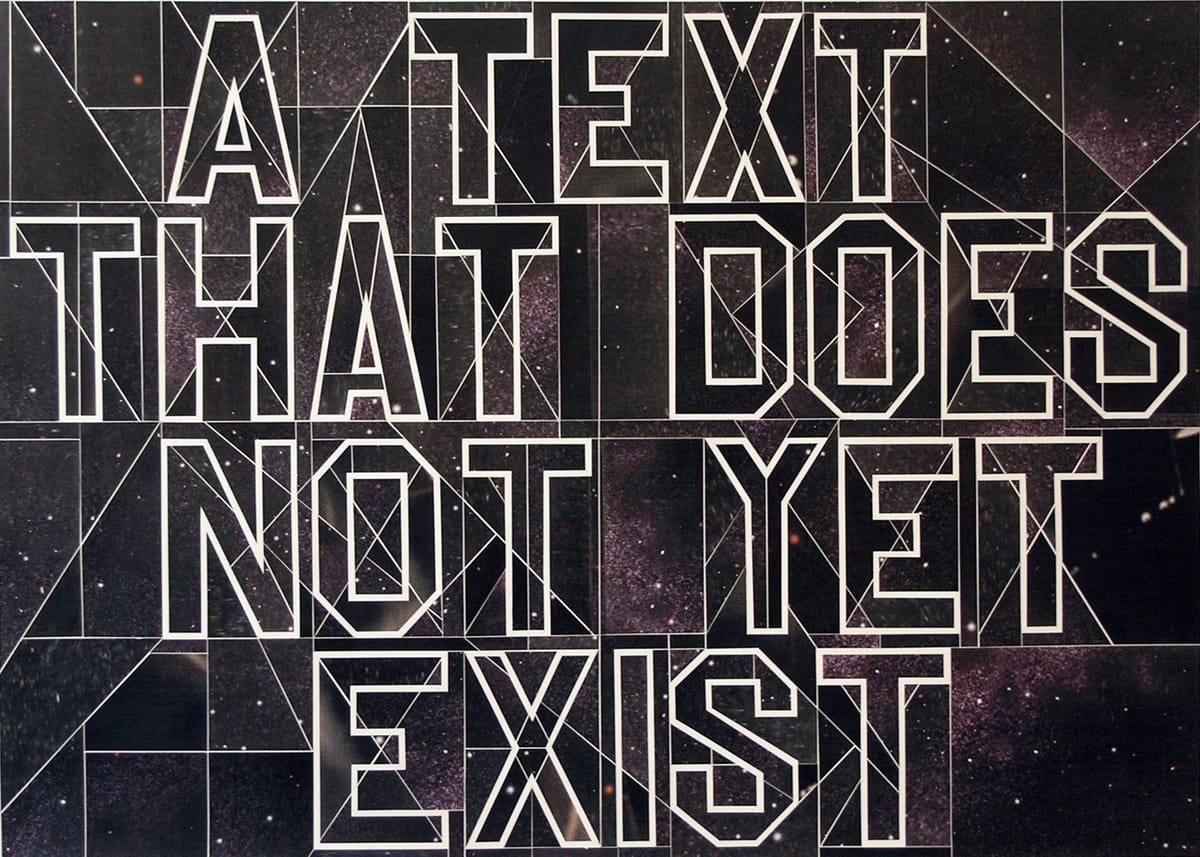

Good thing I’d told it all good riddance. Good thing I couldn’t be bothered with distraction any longer. The seeds for my own writing that would sprout during my time-out would surely blossom into a larger project—a novel, a screenplay, or something else unheard of that would have never been possible to cultivate with my refreshed Twitter page adjacent.

That evening, after several pieces of blackberry tart and everyone in bed, I opened my laptop, ready to spill out extended stretches of writing.

But with the blue light of my screen blinking on, I fought the impulse to click on my browser. I’d saved one window, my personalized home page with headlined links from news sites, updates and tweets from the moment I’d downloaded the RSS-fed page.

Each link looked more interesting now that I couldn’t click through it.

I would have read the shit out of that story on the debt ceiling. My friends and fellow followers looked more fascinating now. I wished I could go over their profiles; I hadn’t delved into what was happening with any of them. If only I could get into the details.

I wrote out a status in a Word document that I saved for later.

I make tart from blackberries, not calls.

I thought of another: Online absence makes the ♥ grow fonder.

But my lone larger insight was that I’d been hiding behind jokes. I’d disguised myself in cleverness. The suck exacted by the internet had been causing my narratives to separate, specialize, and winnow into the required fields. I needed more time to shake its lingering effects.

I closed my laptop and stepped into the backyard.

The countable stars were in the trillions. Their shine was alive, winking there in the pitch black. The constellations had dimension.

Still, I couldn’t help thinking of the weird miracles happening online.

The next morning, we drove to a nearby flea market. This was a French brocante, selling antique items of all sorts and in various stages of wear. I found a table where a short man with a wine-red nose stood behind stacks of old books. He hawked a collection of gorgeous leather-bound volumes of familiar names like Voltaire, Maupassant, and Johnson, and unfamiliar ones like Jouguet and Mondiano.

They were like bibles, meant to stand proudly on a shelf and/or receive careful coddling. Reading them felt like less of a priority. They existed now to be possessed, first and foremost, and to be shown off. The classics belonged to you, and vice-versa. The only thing that made them different from a Holy Bible was that, in France, no one would thump these books.

As I lingered, the merchant drifted my way.

“Voltaire. Only the second printing. Very rare,” he said to me in Burgundy-accented French with tightly rolled R’s.

“How much?”

“120 euros.”

“What?”

“You’re charging Parisian prices!” my wife stepped in to haggle.

“No, not at all,” he said. “You won’t find editions like this anywhere else. I should be selling for much more. But I’m only here for today.”

“30 euros,” she responded, as though even that were a stretch.

Showing offense, he waved us away.

“Have you read Voltaire?” I asked. The seller looked confused at my question and wild change of subject.

“I can promise the pages are in excellent condition.”

“No, I mean, the words. Have you read it?”

He shrugged. “Sure.”

It was not the point. People should have either read the Voltaire long ago or pretend they did and move on just to possessing Voltaire on their equally antique bookshelf. Whatever ideas of enlightenment could be found inside were now secondary.

We drove away from the brocante. Our only purchases were two dolls from another seller that my daughters had decided to spend their piggy bank centîmes on. They combed the dolls’ hair in the backseat until the winding roads back home lulled both of them, along with my wife, to sleep.

Something called Google+ had emerged. The internet had changed its face again. I soon found myself watching, in its entirety, a video of Charlie Sheen getting booed by fans.

As they dozed in the car, I took a chance to stop into the neighboring town with a regional tourism bureau that offered free internet access. I whispered to my wife that I’d be right back, just needed to check my email.

I logged in quickly. Financial markets had crashing and riots had erupted in England. Dominique Strauss-Kahn remained unjustly held in the U.S., according to the French press. Meanwhile, something called Google+ had emerged. The internet had changed its face again. I soon found myself watching, in its entirety, a video of Charlie Sheen getting booed by fans. I scrolled through the comments not sure what I was expecting.

On Facebook, I typed out an update: This is the age of enlightenment for everyone but Voltaire.

But I deleted it, trying to move on from flippancy, and logged out, getting back into the car as my girls were rousted awake.

On the way back to the house, I got lost. I took a wrong turn leaving the town and drove five kilometers down the incorrect open road, taking us further from home. We passed more grazing cows and bales of hay and unpeopled fields. The occasional villager we did spot only looked more suspicious than our neighbors, part of my justification for not stopping and asking for directions. Besides, I figured they’d only tell me to consult a GPS, which we didn’t have.

Now left to my own devices, as I wandered the area it occurred to me that either the digital world had left my brain scattershot or the peace of the countryside had grown into a loud static that only more visits online could diffuse.

An online life had crept into every corner, whether we were getting a signal or not. Its presence, floating above the hills or racing beneath the soil, had changed our landscape for good.

After drawing out an unconvincing performance of someone who had a larger plan in mind, I consulted a real paper map and managed to chart our way back to the house. As I parked the car, my daughters noticed the local farmer taking two horses for a stroll down the village’s main road. The girls’ delighted squeals said we needed to follow the animals.

I promised myself I wouldn’t bother thinking about anything digital until the onset of fall.

Is it time to forget about summer? The inflatable alligator raft in my trunk says “yessss.”

We had a tranquil hiatus from the up-to-the-minute noise. We returned to the city, having carved a new circle of renewal. We finished a final blackberry tart shortly before school started once more for our daughters. Little had changed when I sat back down at my work desk. I logged on to zero fanfare. I updated my status.

Genuine moments of clarity come in transitions. Who we are and what might become of the acceleration of technology becomes obvious when I conclude at one place and begin another.

It is the back and forth that does the trick, like the burning off of one season into another, reminding us, once more, of last year.

I refresh my homepage and the markets crash all over and rioters are met with the same mace and general lack of interest. I still don’t know whether or not to like an interesting article on a fascinating topic, my intended amour for the sentiment rather than the event. I’m not certain how my sarcasm is being met, nor if my lack of comment on the passing of a celebrity signals contempt for the deceased. I have friends I haven’t sent a birthday cake icon to. I keep meaning to follow others back. There is better that I could doing.

But in a devoted online writing community I comment on a thoughtful, lyrical piece of writing. I type out to her “Thank you for posting this; I enjoyed reading it.” The beauty is still unfolding. The wonder has moved to this space. Wherever this leads, we’re connected and we have something urgent to convey.

I click “post” while the reminder of an open pasture somewhere makes our modern connection actual.