Raising the Stakes

Drooping flowers are no gardener's friend. So how can you fix them? And, more to the point, how did these things ever get by without us? A few simple ways to make the world bend to our will.

When I set out to plant my first garden, I had no idea how much help the plants would need. I assumed (incorrectly) that given good soil, the right amount of sunlight, and a reasonable amount of water, a garden would grow. Perhaps not thrive, perhaps not win awards, but these were not my goals. I had in mind something blurry and hopeful, a bit like a Monet, it seems to me now: an indistinct patchwork of color, dappled shade, baskets of flowers. A landscape architect who came to assess our lot’s potential spoke of the “gin-and-tonic walk” he takes every evening with his wife, a stroll around the garden as the day comes to a gentle close, so I think it’s fair to say I was misled from the beginning.

Here’s an idea: Has anyone ever considered the very real possibility that Eve just wanted Adam to do a little weeding? What was the maintenance plan for Eden, I wonder? Because as far as I can tell, there is no easy, gardening-for-dummies option. The minute you put plants in the ground, you have a situation on your hands. You can let nature take its course, the no-maintenance approach, but I’m telling you that what you will have then is not a garden, but a mess. Pests, molds, mildews, mushrooms—they love the neglected garden. Not to mention the ivy! Along with cockroaches, that stuff will one day inherit the earth. Recently I saw members of a church garden committee planting new ivy seedlings around a statue downtown, and I stood for nearly 10 minutes, mesmerized. Truly a case of the good doing the devil’s work.

At any rate, the no-maintenance approach may result in something you find pretty, but it will be so in the same way a young child’s drawing is pretty—not something anyone outside the family comprehends. Friends will come over and say, “It’s lovely. What is it?” and you will crouch by the ivy-strangled coreopsis, or tenderly lift the moldy daylily, tilt your head, and smile obscurely.

“Benign neglect” is a matter of interpretation, apparently.

So this summer I tried harder, aimed for a low-maintenance approach, if you will, and now I know a few things. For example, flowering perennials come in three varieties. First, there are the ones you have to pinch back all summer so they won’t bloom too early, the overeager little monsters. Second, there are the ones you have to dead-head if you want them to bloom for more than two days. They have to be coaxed along, as if the spectacle of their own faded blossoms depresses them. Trim here and there and the delicate things perk up a bit. Pathetic.

And finally, there are the plants that grow well all summer, slow and steady: asters, some lilies, phlox, delphinium. They seem to be pacing themselves well for a late finish but then, in the home stretch, just as the flowers are coming into their full glory, the stalks give out and the plant falls over! By August, my garden had collapsed, and I ask you, what kind of a plant can’t stand up on its own? How did it survive in the wild?

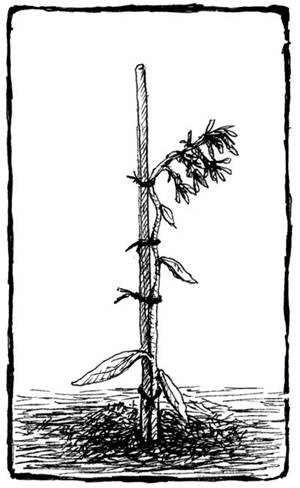

After a day or two I went out and staked the plants, but apparently this wasn’t soon enough for them. The flower stalks had already reoriented themselves toward the sun, so when I staked them they looked like this:

A bed of hostages was not what I’d had in mind.

I called Mr. Gin-and-Tonic, and he told me the English have a solution for this: pea-staking. You save twiggy branches from the “fall cleanup” (this didn’t sound familiar, but I let it go) and lay them on the flower beds in early spring. The plants grow up through the brush, supported by it all season. It’s one of the most natural staking methods, he said, adding ominously, “when done correctly.”

“Of course,” I said.

I loved the idea. The image of the old supporting the new made sense to me. While he recommended certain kinds of brush (birch, pin oak, and buddleia work well), I reflected on how cities are built layer upon layer, nurse logs feed the roots of forest saplings, old scholars hang on to academic departments while the young do battle through the thicket of their work. I suppose I’m not the first to find the metaphorical power of gardening staggering. My train of thought, however, was interrupted by a woman yelling in the background.

“Got to go,” the architect said.

“Is something wrong?” I asked.

“Left the sprinkler too long on the roses.”

“Oh, right,” I said.

Gardening strains a marriage, no question, so it was nice to hear my husband the other day addressing his collapsed tomato plants with disappointment equal to mine. “How exactly did you survive in the wild? What would you do if I wasn’t here?”

I haven’t let him in on the pea-staking tip. I’ll have to see if there’s enough brush to go around.