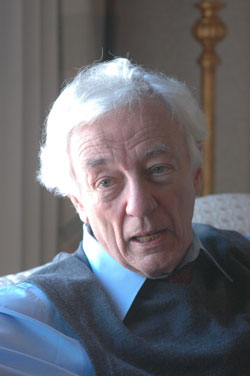

Richard Reeves

The fascinating author and journalist Richard Reeves talks about writing Reagan, founding New York magazine, and covering Lévy's America more than 20 years ago.

A small number of journalists, I believe, inoculated me against the cant and careerism of contemporary journalism—I.F. Stone, Murray Kempton, Mary McGrory, Robert Scheer, and Andrew Kopkind. Richard Reeves is one of them. The reasons become self-evident when you read Reeves’s take on immigration, for instance, in his latest column where he observes:

The long border between a poor country and a rich one has created situations that are misunderstood in many other parts of the country, including Washington, D.C. The ties that bind and the pressures that separate across that border cannot be unbound or relieved by lawmakers or more fences…None of this is likely to change until there is more income parity between the national neighbors. Americans make four times and more what Mexicans make. My friend Andres Oppenheimer…of The Miami Herald…says the flow of the poor coming north will end only when that ratio gets close to 2-to-1. And that will take a long time—or it may never happen, and this problem will be debated and fudged by politicians for our lifetimes.

And in case it’s not self-evident, I ask you to consider: Who today is writing with this kind of clarity of voice and decency of concern? Sadly, I’ll wager you won’t come up with a long list.

Richard, at age 23, founded the Phillipsburg Free Press in Phillipsburg, N.J.; has worked at the legendary New York Herald Tribune, the New York Times, and Esquire; and was a founder of New York magazine. Included among his numerous books are A Ford, not a Lincoln; President Kennedy: Profile of Power; What the People Know: Freedom and the Press; President Nixon: Alone in the White House; American Journey: Traveling with Tocqueville; and now President Reagan: The Triumph of Imagination. Reeves has received numerous awards for excellence in journalism and continues to write a syndicated column that appears in more than 100 newspapers. Reeves is a visiting professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California, and his projected books include a history of the Oregon Trail, a recreation of the experiments of Nobel Laureate Ernest Rutherford, and an account of the Berlin airlift (June 1948 to September 1949).

In the chat below (my first with Reeves), we talk about journalism and history, assessing Ronald Reagan, Bernard Henri Lévy and Tocqueville, what BHL missed, and, well, lots of other stuff. Reeves has a lot to say, and I hope that we can pick up this conversation again.

All photos copyright © Robert Birnbaum

Robert Birnbaum: Are you a journalist who does history or a historian who does journalism?

Richard Reeves: A journalist who does history. I actually have strong feelings about that. The best history in our generation is being done by journalists—whether it’s David McCullough or Tony Lukas or David Maraniss or Taylor Branch. And because classic history was distorting—part of what got me into doing the three books on presidents was that I knew when you read these books [traditional histories], that was not what being president was like. Writing history backward, by its nature, cleans up the messes. So you look at these books and they are done, whether with a theory or by a war or economics, and that makes it all seem neat. When, in fact, I knew in real life all these things were happening at the same time.

RB: I ask in part because I studied history at the graduate level—

RR: I studied mechanical engineering.

RB: When you study history, historians or history professors will sneer at journalism and say, at best, that it is the first draft.

RR: Right.

RB: And the criticism frequently is more negative—it seems to me that the things you just mentioned—

RR: Bob Caro [Lyndon Johnson’s biographer] is another one to add to that list.

RB: Right. The people you mentioned seem to me to be more historian-like than past journalists. Your book appears to be seriously researched with ample citations and footnotes. I wouldn’t, for instance, put your work in the same class as any of Bob Woodward’s books, which are not footnoted and barely sourced.

RR: Bob does straight-out journalism. It’s just journalism in hardcover. And I don’t think the rest of the people we talked about—they are writing history using journalistic technique. And they tend to rely on narrative and also on primary sources and talking to people. In my experience, real historians, and obviously there are a lot of good ones, consider it a negative to talk to the people if they are still alive. That the—

RB: It’s all right to use their recorded recollections when they are dead. [laughs]

RR: Yeah.

RB: But not worthy to deal with them while they are alive.

RR: It’s easier. [laughs] I think there has been a change. I don’t think it’s going to stop.

RB: Also, recently published histories seem to be more readable. And many traditional historical works have turgid prose and no forward motion. Dumas Malone wrote eight volumes on Jefferson. How many people are going to read that, as opposed to Christopher Hitchens’s recent 200-page biographical essay?

RR: The times, they are a changin.’ Writing has a higher value in journalism that in history and I think it’s hard to capture people with a certain old-fashioned kind of history. And even the good-writing historians are—the best example is Doris Kearns [Goodwin], who went from one side to the other, more or less.

RB: Hasn’t she always been considered a serious scholar?

RR: Harvard didn’t think so—they wouldn’t give her tenure. That’s when she began to—I don’t know how that works.

RB: Not necessarily the right test.

RR: You don’t need tenure. The best thing about being a journalist is that you become one by saying you are one.

RB: That’s exactly right. It’s quite wonderful.

RR: It’s the greatest thing. And our generation, the stories—civil rights, Vietnam, Watergate—who would want to be anything but a journalist? In those days you could really make a mark.

RB: It is a self-affirming calling. Unlike writing fiction, has there been a burgeoning of journalism schools? They haven’t grown in the exponential way that writing programs have, have they?

RR: But they have grown. Too much. I teach journalism. They have grown too much.

RB: Because?

RR: Because of Woodward and Bernstein and because of what we are talking about. So many people wanted to become journalists and two things happened. One, the universities picked up on it—offering a doctorate in journalism, give me a break. The other thing was that the number of people wanting to be reporters multiplied and at least the big journals, starting with the New York Times, wouldn’t even talk to people if they didn’t have journalism degree. Usually a master’s from Columbia. So they used it as a way to cut down the pool.

RB: I like the notion of being what you do—not just what your credentials are. This seems to be especially an age in which people acquire credentials and pursue careers because they are careers, not because they are callings or professions. Very different from when you and I grew up. Which is why there were the Jayson Blair, Stephen Glass, Janet Cooke, and Mike Barnicle episodes. People manufacturing stories and frequently their own, fueled by raw ambition.

RR: Journalism provides a big market. And now, with the net, it’s a much bigger playing field and some of the people are offsides or something.

RB: Getting back to historiography, in your bibliographical note mentioned there are 900 books on Reagan, and you cited three. The later Lou Cannon, Reagan’s own autobiography, and then Edmund Morris’s Dutch. My recollection is that when the Morris was published, it was seriously discredited because of his narrative technique.

As far as I can tell, Ronald Reagan is still president. And he’s not the perfect guy those 900 books say he is, but he is running the country the way Roosevelt was running the country, years after he died.

RR: It wasn’t his narrative technique. He fictionalized some of it.

RB: That’s what I mean.

RR: Oh, by technique—yeah, yeah.

RB: That he presumed or assumed certain conversations that he couldn’t have been a party to.

RR: Right.

RB: And therefore people asserted that the whole book was illegitimate. And so I never looked at his book. Yours is the first book I have read on Reagan.

RR: Yeah, good. Jesus, I hope that everybody—I’m kidding. [laughs]

RB: You did remove some of the scales from my eyes on Reagan. I had always dismissed Reagan as a puppet and front for an evil right-wing cabal. That he was a doddering front man for a group of felons. The felons part may still be true.

RR: Yeah.

RB: What is your view of Morris’s book? Despite the fictional leaps, it grasps the Reagan story?

RR: No. I’ll talk about Edmund’s book because I admire the guy in some ways. His Teddy Roosevelt stuff is great. But there is stuff in there that you couldn’t get anyplace else.

RB: Because it was authorized.

RR: Yeah, he was some allowed places that other people could not go. This is, for what it’s worth—and we are friends and this is a brilliant guy—but Edmund’s problem, in that book, it was that he is not an American.

RB: [laughs]

RR: He’s talked to me about this. Edmund was born in Kenya and brought up there and he was this very smart colonial kid. He realized at some point, he told me—I think he was 12 or 13—that nothing happens in the Southern Hemisphere or nothing counts that happens there, and he was desperate to get to the Northern Hemisphere, which he got to by way of South Africa. Which is closer, intellectually, and then he got to London and was an ad copywriter, but inside he was this kid from Kenya trying to figure out how to make it. And out of that I think he thought that Reagan was like him. And he kept looking for the secret, the Rosebud of it. And there is no Rosebud. Ronald Reagan, to me at least, is a made-in-the-USA product. Everything about him seemed easily understandable to me. There was no great mystery, but Edmund was looking for the final clue and I don’t think that that existed. A kid growing up in Dixon, Ill., in those years and whatnot, like you or like me—Americans thought they could do anything they wanted. The angst that Edmund had about himself didn’t exist in Ronald Reagan and doesn’t exist in me.

RB: Let me go backward from the ending. In the closing passages of this book, you quote Steven Weisman of the New York Times during Reagan’s burial week to the effect that the Reagan that was being represented was not the Reagan that he had been acquainted with. What did that mean?

RR: [What that meant was] that the legendary Reagan [who was] being promoted by renaming airports and highways and which was the Reagan presented after he died—I came to believe he was larger than life—the quote that meant something quite different was the George Bush quote after the assassination attempt, “that we will act as if he is still here.” As far as I can tell, Ronald Reagan is still president. And he’s not the perfect guy those 900 books say he is, but he is running the country the way Roosevelt was running the country, years after he died. The quote from Steve was about the fact that they were able to Lincoln-ize him in three or four days. It was really quite extraordinary. But they need him to hold together the conservative movement because the Christians and the libertarians and the fiscal conservatives, the old traditionalists, would spin apart like a [broken] atom if it weren’t for the nucleus of Reaganism.

RB: What was your starting point in writing this book? You open the book by explaining your early contacts with Reagan and you allude to the very different politics—did you start with a blank slate? Were you up-to-date on him when you began?

RR: No I don’t think I was up-to-date when I started but up-to-date enough on one subject, and that was [that] I knew Reagan was underrated and I knew, even when I was underrating him myself as a syndicated columnist or journalist or whatever, that his instinct—he had never been to the Soviet Union, I had worked there. And I knew that there were aspects of the Cold War that (talking about from the Left) that were a joke. [You knew] these people were never going to beat us at anything, if you spent time in the Soviet Union. He came to those conclusions—he had never been there—by reading right-wing tracts and by however his own head worked, and I knew and agreed with his rejection of containment and détente. And I knew that none of my fellows, that is, other liberals, or even guys like Nixon and Kissinger, believed that. And I thought that while he was doing it, my instincts were [that] Reagan knew what he was doing about that and we wouldn’t give him credit. That was one bias, and the other bias, which I can’t resolve, [is that] the guy made his reputation by attacking tax-and-spend liberals, and then he created borrow-and-spend Republicans who may be killing the country. I mean, we don’t know, because we are not going to pay that debt. Our children and grandchildren are. And how much the Chinese are bankrolling us right now, if we are over-leveraged like people with credit cards, then that was his fault—he didn’t mean to do that, but in the end, cutting taxes meant more to him than actually cutting the deficit. The other bias was that the guy was so good at turning issues into emotions—not just to values but to emotions—that he was the big figure in dumbing down American politics and creating this reality world, which isn’t real. The blending of fact and fiction, of entertainment and reality that he used brilliantly in politics now is the American dialogue. And truth doesn’t mean what it meant before. Truth didn’t mean to Ronald Reagan what it meant to me and doesn’t mean to America now what it meant before he came along.

RB: There is that quote that often reprised by some senior White House adviser talking about how the administration now defines reality. It’s what they say it is.

RR: In the Bush White House, right.

RB: So I did have this perhaps ideologically grounded dismissal of Reagan, but I agree with your assessment. I guess my problem was I thought he was a poor actor—a B-actor in Hollywood and he, to me, was unconvincing. Apparently he was convincing a great majority of Americans that it was morning in America, that he was truly affected by certain events and situations. So that’s the part that troubles me. And there is much evidence that you present that he was really a cold, detached man and that the only person he was close to was Nancy. So I guess there is truth in the subtitle of your book, the power of imagination, to create this non-real—

RR: America. That we wanted to believe in.

RB: The power of people wanting to believe this mythic stuff. I didn’t find him convincing and thus failed to credit his ability to convince many, many people.

RR: I didn’t find him convincing while he was president. I never voted for him. But America, going back to something we said before, America is whatever we say it is. We have no sense of history, we live in the present, totally different and I am not against that. We are not fighting wars, like in Kosovo, for something that happened in the 11th century. And because of that, the way we developed, or at least I would argue American exceptionalism has to do with the fact that, forgetting that we killed the Indians, that there was this land here and we came from everywhere and we could keep moving on. That’s what I think of American exceptionalism and I believe it’s true, for better and for worse. He believed the same thing. But he believed God wanted it to be that way. The “shining city on the hill” stuff, and “last best hope of mankind,” and that was his American exceptionalism, that we were simply better than other people. And he said that over and over again. I am old enough now that I like us—America is a great place—we are different, we are not better. We are a different kind of people and I prefer being an American to being anything else. But I don’t think God had much to do with it. God doesn’t check passports.

RB: I was watching Cold Mountain again and one of the protagonists remarks that, “God must be awful tired, being called upon by both sides.”

RR: Yeah.

RB: This notion of Reagan contributing to America’s dumbing down, I wonder if, putting him aside for a moment, who was the last great president?

RR: [long pause] It had to be Roosevelt. Kennedy was an extraordinarily interesting president but he didn’t end up a great president. Obviously Nixon didn’t. Each of them did great things sometimes. But all around—Reagan modeled himself—you say he wasn’t a great actor, [but] he was good enough to play Franklin Roosevelt and he was a professional in a world full of amateurs. There is a great line in his first autobiography, Where’s the Rest of Me, which was written before he was governor of California, that I always remembered, which was, “Most people only know themselves by what they look like in a mirror. A real actor understands what he looks like from every angle and what effect that has on people.” And he may not have been the greatest actor Hollywood produced but he was the best actor American politics produced.

RB: I liked the description of the meeting he had with Leslie Stahl at a time there when were questions about if he was still with it. And someone described him as an old lion who—

RR: That came from the Russians.

RB: To the effect of: The prey was 10 feet away, he wasn’t going to expend any effort, and he still looked like he was asleep. But when the prey moved closer he was lethal—

RR: Those are from the notes of the Russian interpreter at Reykjavik that Reagan was the lion in winter, would see an antelope on the horizon and close his eyes, but when the antelope got close enough, he’d fill the sky and the antelope would be gone. Gorbachev was gone. Even American conservatives were saying, “My God, this guy’s going to sell us out to the Russians.” In truth, if you look at the transcripts, which just became available, the official reports on those meetings, he was the winner against Gorbachev. Not vice-versa.

RB: Where is Gorbachev now?

We are a different kind of people and I prefer being an American to being anything else. But I don’t think God had much to do with it. God doesn’t check passports.

RR: He lives mostly in Moscow. He has a worldwide foundation. But he lost his country.

RB: Could anyone have held the Soviet Union together?

RR: No, it was only a question of time. But Reagan made it happen earlier. There is a thing on April 30th at the GW, the hospital where they saved Reagan’s life—and they did save his life—it’s the 25th anniversary of that and they asked me to speak about “Would history be different? What would be different if he had died?” There is no doubt in my mind that George H. W. Bush was a traditional cold warrior. Believed in containment and believed in détente and believed in never trusting the Russians, ever. And the Cold War conceivably could still be going on now. We were going to win the Cold War, once we realized at the Cuban missile crisis, that neither side was going to use those missiles. It was like, is Paris burning? No leader was going to burn down Paris and from that point on, American victory was inevitable. But it wouldn’t have happened as early if Reagan had not first liked Gorbachev, trusted him, and then depended on him, not believed Communism was going to fall of its own weight. Because in the end, Reagan was alone. The conservatives deserted him when he began to flirt with Gorbachev.

RB: What do people like George Will say now?

RR: I’m afraid to ask. In the book, George Will did me a great favor in doing this book. That is—Nancy Reagan called him and asked if she should talk to this guy, this leftie? And Will said, “Yeah you should talk to him. He’s straight.” And so she did and that also meant a lot in that other people would talk to me. But George Will, in the climax of the book, Dec. 8, 1987, when they sing “Moscow Nights” at the White House and two days later George Will says that “Dec. 8, 1987, will be remembered longer than Dec. 7, 1941, because this the day we lost the Cold War.” In fact, it was the day we won the Cold War. But I haven’t had that conversation with him [Will]. And I am not looking forward to it. It’s not only him. All the conservatives were trying to lock Reagan up after Iran-Contra. They thought he had gone dotty and that he was going to sell out the country to this young Communist leader. Today, if you talk to them, they [say they] knew all along.

RB: And they extend his prescience to all sorts of matters.

RR: Right. They were his biggest problem in that period.

RB: Your claim is that he believed in the inevitability of Soviet downfall—he had a sense of it. Which sounds right. But his hagiographers make a broader claim. He actively worked and manipulated and structured events. That he was the reason we won the Cold War. His “we win, they lose” strategy was pretty simple.

RR: When it works. We were talking about the number of books written about him, Many of them have to do with his mission to bring down Communism, and by those books it started when he was four years old—he had a vision. When he was four years old, I think he was born in 1911, so what Communism was there? I have been surprised by some of the reactions to my book by conservatives who don’t want to give up that myth. That he was born and that was his mission and God and SDI [the strategic defense initiative known as “Star Wars”] and all that becomes part of it.

RB: Did he really believe in SDI?

RR: I think he thought it would work. I think he thought Americans could make anything work. It was all [a] Hewlett-Packard-in-the-garage kind of thing. But one thing the book brings out is that—I didn’t realize before I started—that his biggest foreign policy adviser was really Nixon. He talked regularly to Nixon; if you looked at his telephone logs, Ronald Reagan characteristically spent two or three minutes on a phone call but with Nixon it was 40 minutes. And Nixon always saw [SDI] as a fantastic bargaining chip: He didn’t even have to build it, he could use it to bargain. Then it actually falls off the table when Gorbachev releases Sakharov from internal exile and he comes back to Moscow and Gorbachev meets with him and asks him about whether it [SDI] is possible. And Sakharov says it’s not possible. But even if it were possible, it all depends on hitting them [the missiles] as soon as they are launched. And after that, at the Washington summit in December of ‘87, Reagan tried to bring up SDI and Gorbachev said, “Forget it, do what you want.”

RB: I started to ask you about former presidents. You mentioned FDR. The more specific issue is, is there a decline in the leadership caste—has there been a lack of quality political leadership?

The most important thing about Reagan, in the end, was that he was old. He didn’t want to know anything new. He didn’t want to control everything. He didn’t want to know everything. He didn’t care what people were saying about him in the way that a Nixon or Kennedy cared.

RR: There has been a decline because there has been an increase in the amount of communication in the country. Presidents used to have the power—if what the people know and when they know it is the engine of democracy, and I believe that, people now know more and they know it at the same time the president knows it. So a president can’t do what Roosevelt did with Pearl Harbor, what James K. Polk did with gold in California. That is, manipulate the information, which is different than “spin.” Literally, the ability to keep the information from getting to the people—that no longer exists. So any advance in communication probably leads to a decrease in the power of leaders.

RB: What about the values of leaders?

RR: Which?

RB: The kinds of values that the leadership class displays? The things they believe and what is permissible and not. And how that lines up with notions of governance?

RR: I think polling killed that.

RB: [laughs]

RR: I do.

RB: Focus groups and such?

RR: Yeah. That totally changed the way leaders led.

RB: Wasn’t there polling in the ‘30s?

RR: Gallup invented it, when his mother-in-law ran—it’s a great story—his mother-in-law ran for secretary of state in Iowa. He was a professor back East. I’ve forgotten which school. [George Gallup briefly taught journalism at Drake, Columbia, and Northwestern universities and was at advertising firm Young & Rubicam when he first conducted public-opinion surveys for his mother-in-law, Ola Babcock Miller.—eds.] He came back to help with her campaign and he went door-to-door for her and after a time—Iowa is a small state—he realized that the same answers would come up. He began to think in terms of, you learn as much talking to a hundred people as you do to a thousand and then he created the theories that became statistical probability, black balls and white balls, and invented what we call polling. Scientific research, but it didn’t really come into usage until at least the ‘50s. And then it was much less—

RB: How much did Reagan depend on Richard Wirthlin?

RR: Not a hell of a lot, I do think.

RB: His name keeps coming up.

RR: He was there, and they were polling every week. I think he [Reagan] factored it in. But the thing was—the most important thing about Reagan, in the end, was that he was old. He was an old man. He didn’t want to know anything new. He didn’t want to control everything. He didn’t want to know everything. He didn’t care what people were saying about him in the way that a Nixon or Kennedy cared. Younger men who cared about everything—the point was that the greatest power that polling had on Reagan—he only believed four or five things and he was going to do them anyway. However, in the last two weeks of the 1980 campaign, Wirthlin’s polling showed there was a massive shift of voters toward Carter. And for the first time in their internal tracking polls, Carter was even with Reagan and the reason was that women were shifting from Reagan to Carter because they were afraid of war. They were afraid that Reagan would get us into a war. And Reagan met with Wirthlin and other hired hands he had at the moment, and it was out of that the next day he announced he would put a woman on the Supreme Court. And then the shift of women from Reagan to Carter stopped. In fact it backed up. And that led to Sandra Day O’Connor and other things. But in polling about attitudes toward the Soviet Union and stuff like that, which had great effect on Kennedy and Nixon, particularly Kennedy, didn’t have any effect on Reagan. Polling on taxes had no effect on Reagan.

RB: I looked with newfound respect on his interest in Calvin Coolidge. There is something to be said for a management style that says, “Don’t do anything you don’t have to do.” In a job that is all-consuming and relentless, you could always find something to do.

RR: Right, that’s why Nixon never wanted to sleep. There is always something you can do.

I grew up in Jersey City, which was like growing up in Boston. I thought America was an Italian country governed by the Irish.

RB: Do you have sense that in a way that Reagan aged less in office than most presidents did? Because he was more relaxed about it.

RR: Yeah, if you look at the presidents in the pictures as they change, and only 43 of them know—we don’t know. You’ve got it. It’s that drive—look at Bill Clinton. The drive to use that power, to do something. Reagan didn’t. He wanted to cut taxes, to cut the size of government. He wanted to roll back the Communists. He wanted to make America proud again, as he said. And he wanted to increase the military share of the budget. He was right. We don’t pay the president by the hour. The other guys were wrong. It’s what killed them. Nobody remembers what Lincoln’s agricultural policy was and Reagan didn’t have one. He didn’t care.

RB: Except for the subsidies.

RR: He continued them. That actually was polling—not so much polling, as you would lose a couple of states if you eliminated them. That he considered a small thing. So he sold the country out on stuff like that. It didn’t bother him at all. That isn’t what he felt he was there for. He was there about Communism and the size of the government.

RB: Why do people want to be president?

RR: They are self-selected today. So they choose. It’s not a system anymore.

RB: No one is waiting for the messenger to come down the farm trail.

RR: They are megalomaniacs who can’t get satisfaction in private and need public—like actors—and need public acclaim. They are strange people. And when a normal guy like Gerry Ford is as normal a president we have ever had—he really never got the job. He had the job but he didn’t get it.

RB: Harry Truman, was he normal?

RR: He was probably normal, yeah. He was a normal human being but, well, actually we have answered the question, neither of those guys was elected. Neither of those guys selected themselves to be president.

RB: Truman was elected in ‘48.

RR: He never would have been a candidate if Roosevelt had not died.

RB: So what’s your reaction to the flurry of interest around Bernard-Henri Lévy’s American Vertigo?

RR: I take it personally.

RB: [laughs]

RR: I wrote that book 20 years ago. More than 20 years ago. I retraced Tocqueville’s travels for American Journey and I thought I did it better and smarter than he did. On the other hand, I read only the first take in the Atlantic and I thought, this is horseshit. I didn’t—I know he is a smart guy—I didn’t feel the way Garrison Keillor did.

RB: That was horseshit. It was embarrassing.

RR: Yeah. Lévy doesn’t get America and we don’t get France.

RB: I thought the smart review of that book was Marianne Wiggins in the Los Angeles Times.

RR: Yeah, I read her review.

RB: She opined that Lévy’s book was a Vanity Fair take on America.

RR: The real Vanity Fair, not the magazine.

RB: I liked what he wrote recently in the Nation about the embarrassing lack of an effective left-wing opposition in this country.

RR: I didn’t read it but I agree [with that claim]. He’s right. America needs a Left, desperately.

RB: I hope that the terrible rightward swing in the country may have taught people a lesson.

RR: That will happen, but we will pay a high price. If someone asked me what should happen in Washington—the entire congress should be impeached. They are the ones who are not—the press is doing a bad job for explainable reasons, but the Congress is doing is no job whatever.

RB: They are of the same ilk, the same generation of ambitious careerist people—

RR: Waiting to see what happens. To see which way the tree is going to fall.

RB: I really think they are crooks. Someone like Mark Twain would have field day today.

RR: I don’t think Lévy spotted something, which I would say though I didn’t spot it at the time or I didn’t know how to express it. There is a fundamental flaw in our society that’s costing us. And this is it, that everything in our structure is related to money. And if money and power are separated, then you are gong to have high levels of corruption and politics is a place where money is most separated from power. These people have great power—you change one comma for Monsanto in some bill and they make billions but you are still paid $140,000 a year. Which sounds like a lot of money to the general public but doesn’t pay the tuition if your kid goes to Harvard. Our political system is deferred compensation. You get to make speeches or do it after you are in office. But the corruption of the Congress makes them sitting ducks for people with money. Is this interesting to you?

RB: Sure.

RR: I covered a lot of local politics and loved every minute of it. I grew up in Jersey City, which was like growing up in Boston. I thought America was an Italian country governed by the Irish.

RB: I grew up in Chicago. I thought it was a Jewish country governed by the Irish [Richard Daley]. “Vote early and often” was the reigning slogan of politics there.

RR: So I have seen friends go to jail, politicians and whatnot, and my own take on it was that there is a difference between Democratic and Republican corruption. Republican corruption is pretty straightforward. They see their opportunities and they take them. You watch these guys who have money to invest and blind trusts and all that stuff, and they feel it’s un-American if you know something is going to happen, not to make money on it.

RB: [laughs]

RR: The laws that govern public officials are different than govern corporate people. So some of them, Paul Thayer, who was head of whatever he was head of, who ended up in jail. He didn’t think he had done anything wrong. He just made money. What the hell! The Democrats of my friends, who have gone to jail, got caught with their hands in the cookie jar, had to do—you can almost predict when it will happen. And what it is, is because of the power of office, they move in a social circle, they meet people who are really rich and want something from government and live a certain way. And they allow congressmen and assemblymen, city councilmen to live that way, too. To go to the Bahamas or to do what ever it is. Then comes the day that their children start to go to college and suddenly the rich people’s kids are suddenly going off to the best schools and the politician’s kids, who are usually smarter—no politician can afford forty thousand dollars a year to send a kid [to school]—and that’s when Democrats start to take it under the table. So that they can keep up that lifestyle of the rich, powerful people they now think they are part of. They have no idea that if they lose the election they are not part of anything.

RB: The American way of living beyond your means.

RR: Yeah, and they live beyond their emotional means, their cultural means, and they can get that free. They can go to the best restaurants and do all that and get tables, but what they can’t do is pay the college tuition for a couple of kids.

RB: The phrase “demonic commerce” from Tocqueville is a perfect fit for our era. It’s not in currency, though there is regular and constant interest in him.

RR: It’s no longer demonized. “To be rich is glorious” or whatever Deng Xiaoping said has become—it’s just amazing if you are on college campuses the way kids talk about money in a way we never did.

RB: I love to tell this story about running into my son’s doctor, on the subway, the trolley—a doctor on public transportation—and we are talking and pissing and moaning about this and that. He said, “I’m dismayed that my patients [the oldest are in their teens] know what each profession earns. They are aware of the earning power of various jobs.”

RR: Interesting.

RB: A sign of great corruption. When I wanted to be a doctor as a kid, it was because I was interested in it—I had no sense of their incomes.

RR: I went to an engineering school and the same thing was true. We were there because we wanted to build things but today—I tell two stories. One was Norman Lear and I once had an argument. I was writing about television and he said, “I’ll tell you where television went wrong.” I was then working for the New York Times. “Your fucking newspaper. Publishing the Nielsen ratings, that was the end of good television.” And I have heard—I think I am the villain of the piece. I was one of the founders of New York magazine, and it was all Herald Tribune people, which I was. People have told me when the world started to go bad—we invented printing how much money people made. And then Forbes picked up the 400.

RB: That was an interesting group. Yes?

RR: Which?

RB: Clay Felker and—

RR: Gloria Steinem, Jimmy Breslin, Peter Maas, Tom Wolfe—

RB: Milton Glaser.

RR: Milton Glaser, Walter Bernard. We had all—

RB: What a cool group.

RR: The cool guy was really Felker. In the sense that when we left the Herald Tribune, he was the editor of the Sunday Tribune, which was New York, and it had that logo which was done by Milton Glaser. Instead of severance pay—which would have been $7,500—he took the logo. He said, “Let me have this logo,” and they said, “Fine,” and then he went around trying to get money to get the magazine out. But he understood what you and I didn’t. Americans do ask, adult Americans have always asked, “How much money do you make?” But no other country, I live part of the year in France. No one in France would ever ask you how much money you made.

RB: Was Ed Sorel part of that group?

RR: Sorel was part of the [New York magazine] group.

RB: You look like him.

RR: He’s so fantastic. We covered the ‘76 Republican convention.

RB: In Miami?

RR: Yeah and I was writing, he was doing the artwork. New York magazine didn’t have a lot of money, so we were rooming together. I come in the room and I see Ed’s packing. The second day of the convention. I said. “What are you doing?” He said, “I hate these fucking people. I have a wife and a family and life at home and that’s where I am going.” [laughs] One of the great talents.

RB: Really!

RR: These were guys—Milton Glaser went to an advertising art exhibit because he did that as well, and saw these little drawings by this guy nobody ever heard of and said we should hire this guy. It was David Levine.

RB: Another great talent.

RR: Now talent is more public. There are very few discoveries, it seems to me. Everyone is promoting themselves. All the time. It’s probably a corollary to Warhol. No one is unknown anymore.

RB: Are you still working on a book on the Oregon Trail? [laughs]

RR: Well, I’ve got a manuscript on the Oregon Trail, a 30,000-word manuscript which needs work and I never seem to get to it. It needs more work on the Indians and the Mormons. And the other thing is the Ernst Rutherford thing that I am doing.

RB: From your training as an engineer?

RR: Jim Atlas’s series [is] at Norton and they asked me if I would write a book and then suggested Ernst Rutherford. He was the guy who, in a series of experiments in 1911, worked out what the atom really looked like. He has won a Nobel Prize for work that led to the periodic table. Rutherford was the last experimenter. Niels Bohr was a student of his for a time and really developed quantum mechanics; at that point you couldn’t do it with your hand s anymore. You couldn’t see. And so what interested me about Rutherford was that he was the last guy who really would take an old bicycle pump and figure out what the atom looked like. It was the scattering experiment, which depended on radiation, but he was able to do it. He had this young guy working with him, Hans Geiger [of the Geiger counter] and figured out pretty much what we think the atom looks like. Maybe they will discover something tomorrow and find out we were wrong. But my conditions with Norton were that I’d set up a lab and redo the experiment. And I did. I went back to my college, Stevens Tech, and worked with the physics department and redid the experiment. And when I stop selling my ass on this book, I have done the work on it, I’ll sit down and write that. I look forward to it. The book I want to do after that, I think I want to do it. I’ll put off the Oregon Trail one more time. I have always wanted to do a book on the Berlin airlift. And to write a story that is heroic without killing people.

RB: Under whose impetus was the airlift done? Marshall or Truman?

RR: I hate to say. Truman and Curtis LeMay.

RB: [both laugh]

RR: LeMay is a villain in my Kennedy book and if I do this book, he’ll be a hero. Life goes on.

RB: LeMay makes quite an impression in Errol Morris’s Fog of War, in the section on the World War II bombing of Japan. He sounds like a maniac.

RR: He was a maniac. The great line in the Kennedy book, after LeMay offers to obliterate Cuba, Kennedy says—I forget who he said it to—“Never let that man in this office again.” [both laugh] But he was a hero of the Berlin airlift. I haven’t done enough work on it yet to know where everyone fits in.

RB: No one has done a book on it?

RR: How do writers work? Where do you get ideas? I was reading Tony Judt’s book. [That is, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945.—eds.] It’s really good. And he had one sentence on the Berlin airlift in the book. And I thought, Jesus. And he had a good picture of it. But only one sentence—like it didn’t happen.

RB: What was the picture? Airplanes in the sky?

RR: It was set up with kids in rubble, watching a C-54 landing. And then, just for kicks over Christmas, I was in a bookstore and I looked at [David] McCullough’s Truman and he gives it a paragraph. And I thought, Why is no one out collecting the diaries and stuff? So I may give that a shot when I finish blowing up the lab.

RB: You live part-time in France, part-time in Sag Harbor, teach at U.S.C.

RR: January through April.

RB: Still doing journalism?

RR: Yeah.

RB: And still writing books. Pretty full menu.

RR: I get up early. I do, I get up early in the morning and in afternoon I am usually worthless anyway. But yeah, if you got it, flaunt it. I grew up in Jersey City. No one went to college in the world I grew up in. Even my father, who was a lawyer, never went to college. In those days, you could apprentice and take the bar exam. And then it was Sputnik time and I am in an engineering college. I’m not very good at it. And I kind of get through. I just saw my college roommate, who became the head of the chemistry department at Georgetown, he was smart as a fucking whip. And we were talking about the fact that I would get on the best lab teams—I was the only guy who could write. As long as I didn’t go in the lab and break anything, they’d give me all the data and I’d write the report. So I kind of got through. Then I went work for Ingersoll-Rand and I designed pump systems, and I knew I had to get out of there. I didn’t like corporations. I was a lousy engineer. The guys I worked with were all unhappy. I was smart enough to know that if I stayed I’d end up like them. And I ended up starting a newspaper in the town, with another guy. Then I found out people would pay you to write.

RB: An amazing thing.

RR: I wrote a book report this morning for Duke magazine—they’ve done me a lot of favors and my daughter is at Duke—the other reason I have to keep writing. [both laugh] I can’t believe it every day, that I can get up and people will pay me to write.