Summer Into Fall

New clothes, AP classes, middle-aged angst. A New York City mom reflects on being pulverized by the first day of school.

I woke at six-thirty this morning, hating everyone on NPR for their ubiquitous competence, and knocked at my son’s door. It was locked. This was a first. I was up at six-thirty multiple times this summer through no fault of NPR, which I have studiously avoided. But the locked door—that was a first.

At seven, my son emerged. He was wearing the clothes that he had laid out last night—an overpriced new shirt from Brooklyn Industries the only acknowledgement on his part of this first day of school. I poured him a bowl of Cheerios. He ate three spoonfuls and said he wasn’t hungry. Then my son left to be a high school sophomore, and I went back to bed and pulled the covers over my head.

When I was 15, I adored the first day of school. Thirty years later, it crushes me. If there is an answer as to why this is, I’m not sure I want to admit it.

There’s a particular sound that a marching band makes from the distance of a quarter mile in a small, rural town. It is the auditory equivalent of the smell of burning leaves and the itch of a Fair Isle sweater. It is the herald of fall, the reminder of youth, the anticipation of more. It is the sound of seven o’clock on a Friday in September, and it beckons, defying disinterest in football. It goes duh-duh-duh-duh, doo-doo-doo-doo, dum-dum-dum-splash. It’s the mobile snare set that clarifies the muddled sound of a crappy PA system doing play-by-play; it’s percussion in a chilling evening; it’s the sidekick to the sloppy horns and goofy flutes; but for me, it is the promise that all is going according to plan.

I spent my teenage years answering the call of that drumbeat. When I left it behind, I went on a wild adventure, attended a great college, lived abroad, married, worked, quit, re-invented myself as an anti-careerist, and raised a child. I sat on the stoop while his father took the annual first day of school photo, and for many years, I held his hand on the way home from that first day. This morning, I didn’t go down to the stoop, though his father did. I met one deadline and then retreated into a pity party.

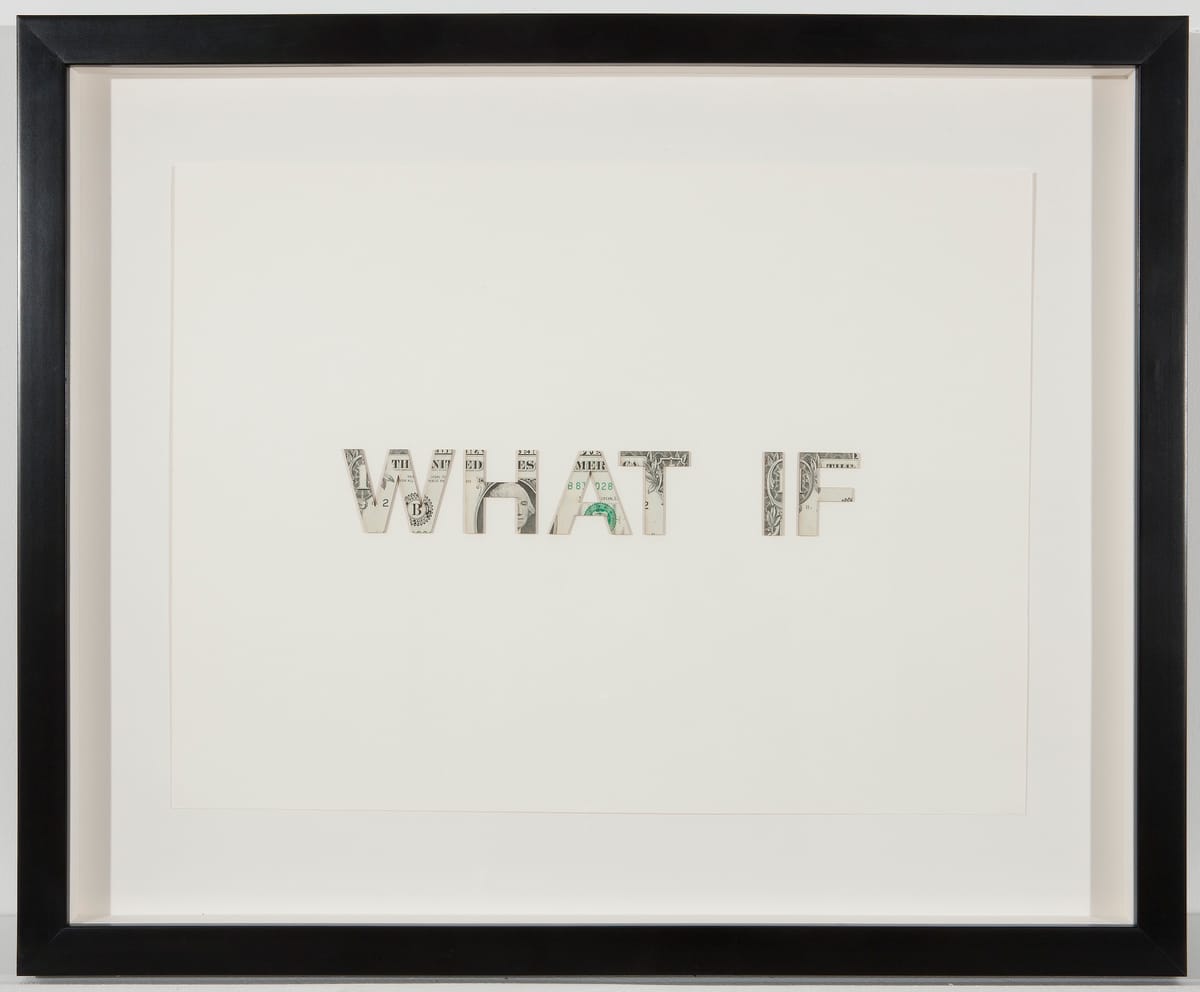

Today—the first day of school in New York City—is hot, humid, and devoid of snare drums. Such a sound is not just miles, but also years away. As my son negotiates a flawed schedule and an undesirable locker, I ask myself a familiar question as the mother of a teenager: “What, exactly, is the plan?”

My son is a New Yorker. He was born and raised in a city that never hears the muffled call of the local high school marching band. Last month, I took him south to the river where I spent my youthful summers, and he and I took midnight swims independently, surprising each other as we came in the back door. I congratulated myself on being a writer whose day job fit into three hours on a cabin porch. I told myself that there could be no coming-of-age without that river, without cousins, without crickets at night, without those solitary swims. I can’t honestly say whose coming-of-age I was celebrating. The day we left, we dropped his cousins off at their first day of school. They were unenthusiastic. But I nearly drove off the road looking at their football field through the rearview mirror.

There’s a particular sound that a marching band makes from the distance of a quarter mile in a small, rural town.

Back in the city, with a week before school began, I dragged my son to orientation. I had volunteered to hand out paperwork and he had agreed to play the seasoned sophomore. I bit my tongue before I could say something mom-dumb, like, “Isn’t it cool to be proud of your school?” On our way inside we passed his peers, students schlepping instruments to jazz band auditions, chamber music rehearsals, orchestra practice, and who knows which else of the other artistic endeavors that go down in one of New York’s most coveted arts schools. Again, it was on the tip of my tongue to comment on his rich high school experience. He beat me to it.

“This is so depressing,” he said.

Today, as I absorb the body-blow of purposelessness that strikes any mother foolish enough to have treated summer as a mission unto itself, I am apt to agree with him.

I don’t remember questioning the purpose of school. The relevance of certain homework assignments, yes. The merit of early school assemblies, yes. The wisdom of those teachers who, as far as we could tell, had been in reverse hibernation over the summer, yes. But the inevitability of a return to hallways and lockers and lunchrooms that did not recognize our ambivalence—that I never questioned. My mother was a French teacher; she had married the chemistry teacher. School is where we all spent our days.

I have forgotten, I’m sure, the frustrations of being a smart kid in a school that counts attendance as sufficient. Surely the caliber of my classes were no better than those of my son’s honors and AP courses, but as I observe his school work I feel certain that the bar has fallen. I have disconnected from the school reform debate because I dislike the debate even more than the results. I am the parent of an honors kid, but if his is a superlative education, shouldn’t he have some inkling that this is the case?

“All kids hate school,” I am constantly reassured. I find this response not the least bit reassuring.

I didn’t hate school. But look where that got me.

I didn’t hate school. But look where that got me. In the decades since my graduation (salutatorian? Cum laude? Anyway, I made a speech), I have dismissed many great ambitions in order to succeed at something greater. Something that life coaches and motivational speakers call Being Here Now.

It’s a good place to be. But it means not being somewhere else all these years. And if I’m honest, I know that it is not my son’s relative lack of enthusiasm for his education that is weighing on me. Nor is it my proven inability to light that spark for him. The idea that I should yank him from school, show him the world single-handedly, blow things up in our kitchen—bothers me only slightly. What nags me more, on this ritualistic day, is the possibility that if he hasn’t learned the things I had hoped from his decade in school, I have learned even less: I have let down the enthusiastic, high-achieving student from Lexington High School, home of the Scarlet Hurricane.

I’m the one who should be going back to school.

I recognize the irony of a middle-aged mother wracked with existential angst. Time passes, kids grow up, empty nests loom and then, our greatest achievements claim their own victories. Hell, I saw Boyhood (which really should have been called Motherhood) and I bristled at what the director did to Patricia Arquette when he handed her “I thought there would be more,” as her last line. What a jackass.

We all know there is more. That is what scares us.

After the locked doors and the Brooklyn Industries wardrobe and dinner debates about the merits of homework… there is more. Once Parents Association meetings are as distant as the prom I didn’t attend… there will be more. Testing and applications and deadlines will pass, my son will leave a dish on the counter and then leave, himself … and there will be more. Of course I know that there is more. Much more. NPR reminds me every morning.

The question is, will I do any better at more than I have done with this? And by this, I mean those last days of summer—days when the sight of my son rushing headlong into the present with no interest in the future is all there is, and I need nothing more.